Architects of Necessity: BIPOC News Startups’ critique of Philanthropic Interventions

By Meredith D. Clark, Ph.D. and Tracie M. Powell

If journalism entrepreneurs are “agents of innovation,” (Carlson & Usher, 2016, p. 563) then the color line compels BIPOC publishers to become architects of necessity, balancing the constraints of digital news production with the information needs of the communities they serve and the demands of the philanthropic support that make their work feasible. In this study, we analyze data from 100 BIPOC news media founders and publishers to focus on the relationships between BIPOC founders/publishers and their sources of revenue, particularly journalism foundations, and examine how policies for obtaining funding replicate normative frames of deficiency and deviance among non-white journalism startups. The study offers a critically informed analysis of journalism philanthropy and the race question designed to articulate the needs of BIPOC media publishers from their own sousveillant position in the built media environment while challenging journalism funders and their partners to make race and difference central to their strategies in equitable ways.

Journalism philanthropy — and with it, journalism entrepreneurship — has a race problem.

While a robust body of scholarship on the viability of news startups offers lessons on the trial and error of building viable nonprofit journalism outlets around the world (Bunce, 2016; Heft & Dogruel, 2019; Usher, 2017), much of the research on similar outlets in the United States remains either indifferent to or ignorant of the needs of news media startups developed by journalists of color, or those who identify as Black, Indigenous, or People of Color (BIPOC). Additionally, scholarship on the impact of philanthropic investment in news media is relatively scant; focused inquiry about how news organizations with non-white leadership even more so. This is reflected in the disparate reporting on how race figures in journalism entrepreneurship and in philanthropy. Attempting to collate data that illustrates the relationship between the two is incredibly difficult. After several years of racial justice protests during the Movement for Black Lives (2013-2016), U.S. news media was particularly primed to be receptive to messages about its implications in racialized violence (Tameez, 2022). It is within this context that we examine the experiences of journalists of color (JOC) as entrepreneurs navigating opportunities and obstacles in obtaining funding for their projects.

This article draws on quantitative and qualitative survey data collected by The Pivot Fund to present a preliminary needs assessment of BIPOC-founded news media startups following the so-called “racial reckoning” of 2020 (Bora, 2022). This research highlights the intersection of two fields — journalism and philanthropy — that have struggled with racial and ethnic diversity, and how colorblind ideologies in both areas further complicates the terrain for entrants from structurally marginalized communities. Our analysis begins with a brief explication of Critical Race Theory’s utility in unpacking the linkages between the two subfields. We offer a literature review that discusses the dearth of research on race in entrepreneurial journalism, and include cursory review of works that detail the philanthropic sector’s struggles with racial inclusion to further contextualize the problem. We provide a brief discussion of our methods, and then present findings that incorporate in vivo reflections from the open-ended survey questions. We conclude by discussing insights gleaned from the survey data, and offer suggestions for the philanthropic sector as it works to improve its understanding of the resources and support that JOC-led organizations require in order to become efficient, sustainable contributors to diverse media environments in the digital age.

Theory

This research is undertaken through Critical Race Theory (CRT), a framework derived from legal studies scholarship used to critique systems of power for evidence of racial bias. CRT is specifically useful in examinations of policy and normative practices that assume whiteness as the default existence, as it address the silences and erasures in hegemonic approaches to academic research by using the perspectives and experiences of marginalized people to develop field-specific approaches that highlight how race and other identity-based characterizations (gender, ability, national origin, etc.) are used as tools of subjugation that attempt to force non-white actors into experiences that conform to whiteness as the norm. Where these attempts fail, the non-white actors and their experiences are considered non-normative and/or deviant. While CRT was initially developed by legal scholars, its application in education, history, business ethnic studies and gender studies and has demonstrated its relevance to interdisciplinary scholarship. For example, LatCrit (Diaz, 2023; Iglesias, 1997) complements the initial developments of CRT by offering five tenets for its application in education research, which we find relevant to this work, as our inquiry similarly challenges the assumptions of American meritocracy and fairness that underpin “imperial scholarship,” which focuses on, cites and reproduces the work of white authors often to the exclusion of PoC. We draw from Malagon et al.’s (2009, pp. 256-257) memo on the utility of combining grounded theory, critical race theory and LatCrit1 to form a theoretical and analytical framework to contextualize both literature and our findings.

- Identify the intersections of racism and other forms of subordination. This exploratory research seeks to highlight the interplay of race and ethnicity between the aims of BIPOC media founders and those of the philanthropic organizations they solicit.

- Challenge dominant ideology and its assumptions. As a bedrock of entrepreneurship scholarship, approaches that focus solely on the political economy of news assume — correctly — that funding is a concern for all startups, yet most fail to acknowledge the historic wealth gap between people of color and whites in the United States. CRT prompts researchers to consider the impact of racial capitalism, a theory that describes “the process of deriving social and economic value from the racial identity of another person [or group]” (Leong, 2013, p. 2153) and racial hierarchies in contemporary settings via lack of financial capital directly (operationalized as eligibility and feasibility) and indirectly (operationalized as viability and desirability) available to BIPOC founders. This tenet prompts researchers to consider the obstacles and opportunities different entrepreneurs face along lines of race, ethnicity, gender, class, ability and the like, rather than assuming equal access for all.

- Commitment to social justice. Ultimately, the goal of this analysis is not to shame, but to describe and diagnose critical disconnects that threaten the success of racial justice initiatives in journalism philanthropy. The analysis includes suggestions for concrete actions that may be taken to address systemic issues that plague chronically underfunded initiatives led by BIPOC journalists.

- Experiential knowledge: As a tactic for assessing the return on their investments, journalism philanthropic organizations invest heavily in program evaluation, thus replicating systems of racial capitalism that force BIPOC founders to “prove” their worth according to a priori measures of success. Without the perspectives of founders, intended audiences and even “missed” audiences, these measures reflect artificial efficiencies rather than authentic impact. Responses to this survey indicate that BIPOC founders’ double-consciousness presents a dilemma on how to report the efficiency of their initiatives: they must show demonstrable influence in their communities and the field, but risk losing or alienating potential funders if they are candid about the difficulties that funders do not see because of their myopic focus on performance indicators.

- Transdisciplinary perspective: Finally, the application of CRT in this study is interwoven with grounded theory analysis of our survey data, creating an analytical bridge for examinations of how race and racial hierarchies link common issues in journalism, philanthropy and entrepreneurship (in theory and practice).

From this context, we apply CRT in our review extant literature about journalism entrepreneurship and the data voids (Golebiewski & boyd, 2019) surrounding issues of resource allocation for JOC/BIPOC-led news startups.

White Normativity in Journalism Entrepreneurship Literature

Sources of revenue significantly shape the entrepreneurial journalism efforts, from nonprofits to venture-backed news outlets, to subscriber-supported operations. Domestic or international, all journalism startups face a common challenge of establishing financial viability. With a few exceptions, as Ekdale (2021) notes, the hegemonic influence of U.S. and European perspectives characterizes journalism entrepreneurship studies (e.g., Carlson & Usher, 2016; Heft & Dogruel, 2019; O’Brien & Wellbrock 2021; Porlezza & Splendora, 2016; Wagemans et al., 2016). Among the limited number of studies of such outlets that extends to the Global South, race is often omitted as a constructed category with the potential to shape an outlet’s mission, scope or sustainability (Harlow & Chadha, 2019). Since the early 2000s, scholars (Costa, 2013; Miel & Farris, 2008; Schiffrin, 2019; Usher & Kammer, 2019) have used business models to build typologies mapping the ever-evolving terrain of digital media startups, including:

- Advertiser-based

- Subscription-based

- Membership models

- Mixed models (featuring a combination of at least two: sales, subscriptions, public funding, sponsorship, membership)

- Venture capitalist

- Philanthropic

Although the digital news era has enabled more journalists to become publishers, either individually or as part of collectives and/or startups, “Silicon Valley ideology,” (Schradie, 2015, p. 67–68) underpins an assumption of colorblind neutrality among founders, funders and audiences — that is, a failure to consider how the social construction of race influences everything from funding acquisition to the positioning of “desirable audiences,” who are willing and able to pay for/sponsor news products. This myopic view of the field doubly marginalizes non-white entrepreneurs in both domestic and international media economies, as it fails to account for the historical foundations through which such ventures become and remain viable.

Entrepreneurial journalism scholarship that focuses on the modalities and means of funding models often does so without much mention of how each shapes the realities of BIPOC founders’ experiences in the field. Similarly, the dearth of data on charitable giving to news organizations founded and run by journalists of color indicates a demand for a needs assessment to determine how well their entrepreneurial journalism initiatives are faring with the money and support they do receive from foundations and other philanthropic agencies.

Philanthropy

Interrogating the problem(s) of the color line is also essential to parsing scholarship about journalism philanthropy. While literature on journalism philanthropy is beginning to grow, questions of how race, ethnicity and other markers of identity factor into the disbursement and acquisition of funding are often absent from its analysis. The philanthropic sector has and continues to struggle with its commitment to upholding white normativity (Villanueva, 2021). Ninety-two percent of all U.S. foundation presidents are white, as are 86% of their executive staff and 68% of program officers — yet only a quarter of all U.S. foundations use DEI frameworks as part of their giving strategies (Dorsey et al., 2020).

In 2020, the Philanthropic Initiative for Racial Equity found that of the $11.9 billion companies and foundations pledged for racial justice work between 2015 and 2020 (during the height of the Movement for Black Lives), only $3.4 billion was awarded to communities of color, and even less — a mere $1.2 billion — was specifically earmarked for racial justice projects.

The report did not provide detailed specifics on the sectors in which these contributions were made (Cyril et al., 2021). According to a report from Media Impact Founders, philanthropic organizations gave $124 million to journalism projects between 2009-2021, representing only a fraction of the $19.6 billion donated to media initiatives by U.S. foundations in the same time period (del Peon, 2021). As noted above, early research on entrepreneurial journalism is plentiful, though it largely ignores how race (and other markers of difference) impacts funding and sustainability among outlets around the world.

Schiffrin’s (2019) analysis of startups in the Global South unites these two bodies of scholarship. Three quarters of the 35 media outlets surveyed sought foundation funding to support their operations, several of which mentioned they relied on donations of space, labor and content to survive. Financial viability was the No. 1 concern among the outlets surveyed, most of which were donor-dependent four years after initial inquiry into their operations. Schiffrin describes a desperate situation: “Donors need to embrace the reality of the situation and accept that many small outlets performing vital public service in their communities will die without their assistance,” noting the reluctance among the donor class to pump funds into such entities while clear returns may take years to see, and more specifically, may not be charted in terms of revenues leading to the publications’ self-sufficiency, but more intangible goods including the circulation of credible information, which in turn is thought to nurture civic participation. And despite foundations’ efforts to preserve outlets’ editorial independence, philanthropic investment does appear to have an editorializing influence on the priorities and perceptions of journalists whose work such funding supports. “In the case of non-profit international news, foundations,” write Wright et al. (2019, p. 2035), “direct journalism (both intentionally and unintentionally) towards outcome-oriented, explanatory journalism in a small number of niche subject areas.” While the authors withhold a value judgment, they note that financial support from foundations, and particularly, their desire to measure “impact,” has a mediating effect on both the funder and grantee’s efforts to maintain the outlets’ editorial independence, and the gestures they take to signal that sense of autonomy to other stakeholders.

Returning to Schiffrin, we note one key observation that may be reflected in the BIPOC media startup ecosystem in the United States: There are some organizations that are likely to always need donor support (2019, p. 10), a precarious state emphasized by the critical function of philanthropic sources of funding for entrepreneurial news ventures, particularly those created by and for people of the global majority — i.e., people of color.

Creating the Other: Integration and Ethnic Media

In addition to being overlooked in literature on news startups, “ethnic” media is often positioned by scholars as the creation of Other/outsiders looking inward (Husband, 2005), rather than the production of news media that acknowledges how its lenses reflect its core audiences as part of a multi-racial, multi-ethnic society (Yu, 2018). Yu’s extensive examination of “accessible” (i.e., published in English or bilingually) ethnic media outlets in the United States identifies 746 outlets with an online presence. Of these, 30% are published by Black Americans, 23% do not specify a particular racial or ethnic affiliation and 16% are coded as “Asian.” Native American and Hispanic/Latino publications each comprise 9% of the outlets, 7% are coded as European, while Middle Eastern and “other” comprise another 3% apiece (Yu, 2018, p. 1984).

The racial formation of “ethnic” media is further complicated by the adoption of “BIPOC” as a term adopted as shorthand to describe Black, Indigenous, and People of Color. Deo (2021, p. 118) argues that “centering particular groups only in name ultimately furthers their marginalization because they remain excluded in fact though referenced in the term, erasing the power that comes from participation and inclusion.” While the fair criticism is fraught with complexities that cannot be adequately detailed in this paper, a CRT critique acknowledges that “BIPOC” is a flawed attempt to signal the significance of how the systematic enslavement of kidnapped Africans and the attempted genocide of Indigenous Americans has been doubly exploited in the U.S. system of white capitalist hetero patriarchy to measure the “progress” of immigrants of color who come to the United States voluntarily and substantiate the mythology of the American dream by assimilating into the “rightful” norms of society. Applied to this study’s attempt to map the population of journalism entrepreneurs of color, the BIPOC journalist/founder label is evidence of what Yu refers to as “the instrumentalization of ethnic media” (2016, p. 344). Its use affirms foundations and outside actors that their work is antiracist by virtue of targeting and engaging with journalists of color, while alleviating the burden of having to disentangle racial hierarchies constitutes a determinant of access to capital among different racial and ethnic groups.

Although constructed categories of mainstream, alternative and ethnic media (often further reduced via racial, linguistic and cultural labels) reinforce notions of difference among journalistic publications, both white, corporate-owned, for-profit media and ethnic, JOC-owned, entrepreneurial and/or nonprofit news outlets have a common goal: communicating with and for the people (Deuze, 2006). The media outlets also share the problem of maintaining financial viability, an issue that has been explored via multiple funding models and in different regions of the world. Although ethnic media outlets may individually struggle to maintain financial stability, the need and demand for perspectives from outside the mainstream is an enduring fact that links every BIPOC-founded outlet from Freedom’s Journal to the digital news media startups of today — a 200-year-old reality periodically revisited by scholarship that has included historical surveys of the ethnic press (Gonzalez & Torres, 2012) and one that demands further recognition in light of news media’s so-called “racial reckoning” of 2020 (Clark, 2022).

Method

Our data, collected between November 2021 and March 2022, are drawn from a survey of 100 journalists of color operating news startups across the country. Select demographic data, and responses to close-ended questions, are included in our findings as they were reported to us. The study presents inquiry on the relationships between these founders/publishers and their revenue sources, particularly journalism foundations, to examine how policies for obtaining funding replicate deficiency and deviance frames of non-white news media among the emergent class of journalism startups. The overarching question for our research is:

RQ1: How does the intervention of philanthropic funding impact the health and sustainability of BIPOC-founded news organizations?

We analyzed the qualitative data using a grounded-theory approach informed by Critical Race Theory (CRT-GT), recognizing the interplay of race and structural power situating funding bodies as racialized organizations (Ray, 2019), and analyzing the data via the application of racial capitalism. We completed two cycles of coding for the narrative responses to open-ended questions (Saldaña, 2009), examining responses for evidence of how race factors into the dynamics of applying for, receiving, and using funding from philanthropic organizations. In the first round, we searched for language indicating a sense of disparity between the BIPOC founders’ experiences and those of non-POC journalists/institutions. We included statements of perception in our analysis as these speak to experiential knowledge, which is particularly valuable in the tradition of Black Feminist Thought, as the framework holds that members of subjugated groups use such knowledge to cultivate practices that help them resist oppression (Collins, 1993). In our second round of coding, we developed overarching themes to describe how BIPOC journalism entrepreneurs process their experiences with grant funders to identify barriers to access, unnecessary complications and potential remedies. Our findings offer a critically informed analysis of journalism philanthropy and the race question designed to articulate the needs of BIPOC media publishers from their own sousveillant position (Mann & Ferenbok, 2013) in the built media environment while challenging journalism funders and their partners to make race and difference central to their strategies in equitable ways.

Ray (2019) articulates four tenets for a critical race theory of organizations, offering a structural critique for identifying and labeling how racial formations exist within organizational formations and practices. Following Bonilla-Silva (1997) and Sewell’s (1992) arguments on race as a significant indicator of how cultural practices influence the distribution of resources, Ray argues that:

- Racialized organizations enhance or diminish the agency of racial groups;

- Racialized organizations legitimate the unequal distribution of resources;

- Whiteness is a credential; and

- Decoupling is racialized.

These arguments are essential for challenging the notion of colorblind philanthropy by recognizing its influence at the micro- and meso-levels of analysis, where ingroup preferences and racialized tracking influence the resources allotted program officers (micro-level) and initiatives (meso-level) designed to specifically target outlets founded by people of the global majority. As our respondents’ initial comments suggest, journalists of color, through their familiarity with racial formations in their previous media roles, are sensitized to these stipulations and special affordances, and recognize how racial difference predicates inequitable treatment.

Results

Journalists of color who work as publishers (39.4%) and/or editors in chief (22%) of their operations comprise the majority of respondents in our survey. They represent outlets in more than 19 states and U.S. territories, and are largely concentrated on the East and West Coasts, as well as in the Southeastern U.S. Sixty-one percent of the outlets represented are for-profit; another 29% were identified as nonprofits, while 10% identified as operations that did not fit either of these categories. The average number of employees among BIPOC-founded outlets is 7.75, which respondents broke down as an average of 6.49 full-time employees (both paid and unpaid), and 5.05 part-time employees.

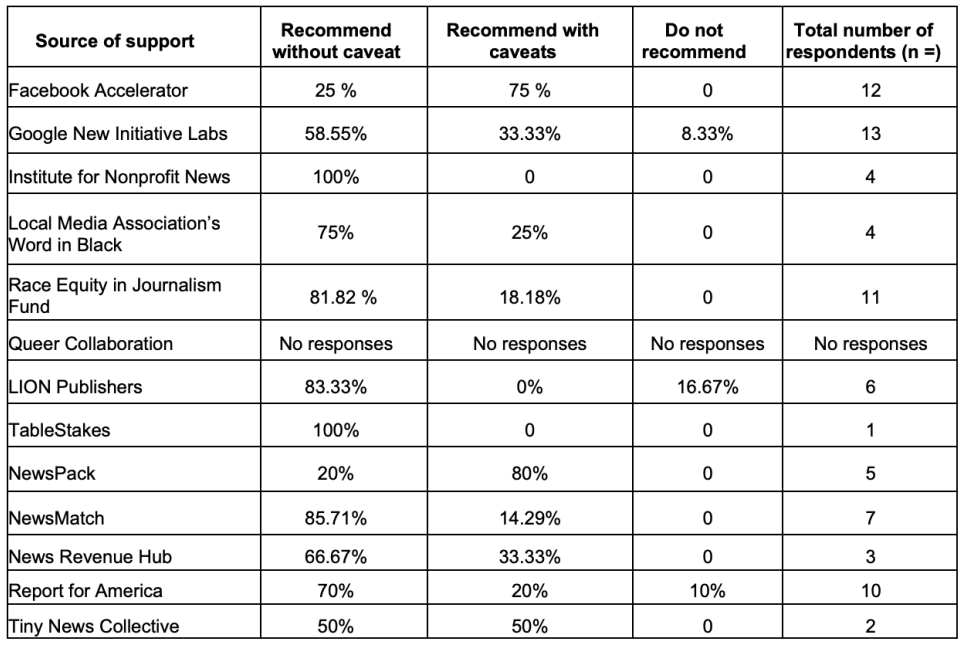

Respondents were asked about the support they received from 12 organizations that provide capital and/or material support (personnel, technology, etc.) to journalism nonprofits and startups, and whether they would recommend the funding agency to other BIPOC founders.

Table 1: Sources of philanthropic support among BIPOC-founded news outlets goes here

Balancing Act: Serving Information Needs and Funding Demands

If journalism entrepreneurs are “agents of innovation,” (Carlson & Usher, 2016, p. 563) then the color line compels BIPOC publishers to become architects of necessity, balancing the constraints of digital news production with the information needs of the communities they serve while attempting to meet the demands of the philanthropic organizations whose funds extend their capabilities. Seventy-nine percent of BIPOC-founded news organizations that responded to our survey stated that current funders are not meeting their primary needs. Most cite the lack of direct, substantial funding that is not tied to burdensome reporting or training requirements. Some of the more pointed critiques came from individuals who had previous experience in journalism, and found requirements to participate in training as a condition of receiving funding paternalistic.

Several respondents indicated that they do not have dedicated staff members, such as grant writers, who can focus on the revenue side of the business, which ultimately sacrifices their ability to report and produce news to the reporting demands required to obtain funding and maintain relationships with foundations. The chief complaints among respondents who disclosed caveats and costs that outweighed benefits on recommending designated funding sources were training and reporting requirements that drained staff time, particularly among organizations that lacked capacity to assign a dedicated team member to complete the funders’ obligatory tasks. One respondent said they would only recommend one of the funders “… if the team has at least two full-time employees whose sole responsibility is revenue. Otherwise, you just won’t have the bandwidth to do the work.” Another voiced a similar concern: “Candidates need to have enough people in the organization to participate; this is not for small newsrooms. Participants have to have a membership program already in place and … do the accelerator to improve it.” These comments indicate that news organizations run by sole owner-operators and/or operations with fewer than four or five staff members experience operational difficulties as an early barrier to fulfilling funders’ intentions.

Echoing Schiffrin’s (2019) observation about news startups in the Global South, the data also make it clear that BIPOC-founded news organizations are in precarious financial positions. Twenty-three of the 42 respondents (54.76%) who answered questions about the health of their organizations indicated that they had cash on hand to sustain operations for three months or fewer, and nearly 17% (16.67) said they didn’t know how long they would be able to sustain their operations at all. Only about 12% of respondents indicated they’d be able to maintain their organizations for one year or more.

Perceptible Inequities

Dorsey et al. identify four boundaries that founders of color face as they attempt to attract philanthropic support: getting connected, building rapport, securing support and sustaining relationships (2020), which corresponded with our data. Eighty-three percent of respondents indicated a belief that white-owned startups are granted more funding through a combination of factors. We refer to these beliefs as perceptible inequity, illustrated through a series of comments about how perceptions of racialized homophily shapes founders’ attitudes about the philanthropic sector’s expression of confidence in white-led initiatives. One respondent, for instance, made explicit comparisons of how whiteness construes a sense of competency among startup founders:

I think white-hype permeates our society and filters down into well-meaning funding organizations. Having white and light skin assigns positive qualities to a person. They are trusted more to deliver on an idea. Whites get more plumb assignments in the news business, which better positions them for high-profile assignments or jobs with big-name media. Name recognition is tied to funding. Those making funding decisions are often white. Whites get used to seeing whites succeed. B1POC (sic) journalistic success isn’t elusive; they aren’t legitimized and promoted in the same way as non-POC.

This reflection illustrates Ray’s assertion that whiteness (and proximity to whiteness) is a credential. In their experience, white identity is a marker of trustworthiness and competency among white journalists and funding organizations. In their previous roles, white peers benefited from in-group status and were rewarded with additional responsibilities, allowing them to develop prominence and familiarity within the field. When white journalists leave legacy organizations to start their own outlets, they leverage the social capital they’ve accrued to initiate, build and strengthen relationships with potential funders, who can in turn point to their track records of success and productivity in corporate settings as qualification and rationale to support their startup efforts. This trajectory echoes at least three of Dorsey et al.’s insights about the four barriers to funding, particularly getting connected, building rapport and securing support (2020). This insight might be further substantiated through a critical-race examination of news media startups that have entered the field in the last five to 10 years, particularly those created or led by journalists previously employed at high-profile legacy news media outlets.

Our organization has been rejected for funding by foundations, or received a tiny fraction of funding relative to “general audience” (white-dominant audience) news outlets, even after winning numerous awards and recognition from peers. This has even been the case when it comes to funds to support reporting on the communities that our organization has a uniquely strong relationship of trust with. Often the reason funders provide is that we are not established or large enough (when history shows that those same funders do not have the same standards for white-dominant news outlets). Occasionally the reason from white program officers has been that they don’t think our reporting will have an impact if it is only reaching low-income communities of color. Other times, it is because journalism funders are focused on sustainability, and they cannot see how a newsroom focused on a low-income audience will be sustainable. Of course, this is just the reality when it comes to foundations.

This respondent’s comments about receiving a fraction of the funding made available to outlets that serve white audiences confirms the first two tenets of Ray’s theory of racialized organizations. The founder acknowledges that whiteness is a credential of relative value, as the “general” or dominant audience is thought of as white — and whiteness is understood as a proxy for wealth and vitality. These assumptions are part of what Feagin terms the white racial frame, “an overarching white worldview that encompasses a broad and persisting set of racial stereotypes, prejudices, ideologies, images, interpretations and narratives, emotions, and reactions to language accents, as well as racialized inclinations to discriminate” (2013, p. 3). Interrogating the white racial frame in media and philanthropy through the experiences of journalists of color is essential, as foundations and their personnel are unlikely to profess openly racist sensibilities. Yet, as Feagin argues, the most significant impact of the white racial frame is that it ignores, downplays, and otherwise diminishes racial realities (2013). The white racial frame is a more explicit articulation of the hegemonic forces that define the “general audience” as one that is white and wealthy enough to support news production through subscriptions and purchases of items that would attract wealthy advertisers. It is the same hegemonic force that is at work when journalists assume that an “objective view” is one that doesn’t take race, gender or other markers of difference that have been used to oppress non-white Others into account (Said, 1978; Wallace, 2019).

Indeed, the respondent identifies their target population as “low-income communities of color,” indicating a relationship between a lack of material resources and non-white ethnic or racial identity. The respondents note that program officers position the community’s lack of capital as a fatal liability. Justification for diminished financial support from foundations is legitimated by the community’s (in)ability to pay for news, even when the media outlet has developed a reputation for serving an otherwise disenfranchised segment of the public.

Two additional respondents spoke of “whiteness as a credential,” the third tenet in racialized organizations theory, highlighting how the colorblind racism inherent to U.S. cultural expectations manifests as ingroup preference for whiteness:

I’ve been told numerous times during the entrepreneurial journey by experts in the field that a lot of the journalism funding world comes down to “who you know.” That itself is a huge barrier and highly demoralizing. For many news entrepreneurs who are first generation in this country, there is no road map. This is the first time that our generation even has office jobs in the U.S. Figuring out how to penetrate the mysterious funding world is a very foreign concept.

This comment comes from a journalist of color who refers to immigration and class markers as proxies for race, and presents a critique of how whiteness is embedded in expectations of social capital (Risam et al., 2022; Royster, 2003). American-born children of immigrants who are the first in their families to have “office” or white-collar jobs are subjected to expectations of cultural competency that are aligned with experiences limited to whites and non-whites whose elders successfully assimilated into the dominant culture. The logic follows that of post-Reconstruction era “grandfather” clauses (used to prevent Black Americans from voting) requiring that an individual’s grandfather had to be eligible to vote in order to qualify (Browning, 2022). While less formalized, the expectation of “who you know,” is a preference that journalists and other professionals of color be well-socialized with cultural expectations of white-collar work and its workers, demands that require a college education and familiarity with the norms of office work (Feagin, 2013).

Everyone wants to know who else is funding you. I used to think they asked because they didn’t want to fund well-funded orgs. Actually, they want to be in good company.

This comment from another respondent bolsters the argument that funders uphold a culture of inclusion/exclusion by relying on informal networks — the approval and literal buy-in of other foundations — as informal qualifiers to engage with organizations seeking aid. Being “in good company,” as the respondent describes it, means that philanthropic peer groups are relying on one another’s approval as an indicator of an outlet’s worthiness. Taken together, these three statements help illustrate how philanthropic organizations reify practices that contribute to the continued marginalization of organizations owned and run by journalists of color. As the potential of return on investment trumps need and efficiency in providing information to poor, underserved communities, the rationale justifying such practices doubles down on the use of constructed obstacles including demands for cultural competency that extend from hegemonic expectations of socialization in college and/or professional settings and culminates in valorization via the approval of peer organizations. These practices perpetuate inequality in access to the financial resources philanthropic bodies offer to those in need (Bird & Ainant, 2022), replicating them along lines of race, ethnicity, and class — under the guise of performance potential and socio-cultural savvy.

Coping with Scarcity

BIPOC-funded outlets face difficulties with funding scarcity even after they earn grants and other forms of revenue. This theme provides perspective that funders are often seeking in their evaluation activities — how are grantees using the money, and how effective is it in promoting the health of their organizations? Unlike self-reports and compliance documents that may be influenced by the recipients’ needs, the nature of our data collection (i.e., from a researcher with no bearing on foundation activities) provides additional context about how even minimal funding serves crucial operational purposes, even as it creates complexities of stopgap approaches to supporting entrepreneurial news ventures.

I haven’t received significant funding (more than $5,000) yet. Getting startup funding is my biggest barrier to operating the way I would like because I’m having to juggle full-time freelance work while trying to launch my venture. Getting a funding boost would be the most helpful to me in this stage, to allow me to build an audience and put out high quality work which would then allow me to attract more funders and individual supporters to make my project sustainable.

Schumpeterian economics (1934) position the entrepreneur as “visionary, optimistic, uncertainty tolerant, rational, confident, self-centered and motivated by power and need for achievement,” a description that remains relevant when applied to entrepreneurs in the digital age and space (Steininger et al., 2022, p. 8). Yet this economic model also emphasizes access to financial resources including cash and credit, and other indicators of favorable social distinction (Foss et al., 2019). As this respondent indicates, infusions of cash into their enterprise would serve as a mechanism for building a profile and producing “high quality work,” which they believe would attract additional funders. These calculations rest on an assumption that the audience is of interest to funders and potential individual investors, and underscores an earlier theme: the ability to attract substantial philanthropic funding is inextricably tied to the ability to be seen/positioned as “worthy” to wealthy, attractive audiences, which, if our earlier respondents’ comments are any indication, are white and/or acceptable to white-normative cultural expectations. Two additional respondents put it more succinctly: “Funding helps you pay off the bills and also function in the current space that you are in,” said one. “The additional resources help us to stay alive a bit longer,” added another, pointing to the limited nature of incremental investment. Yet respondents indicated that small donations and grants are in many cases insufficient to provide the critical support publishers of color need to hire and retain sufficient staffing levels, identifying yet another obstacle:

After receiving funding, we are in a better position than we were before, however, the funds received were not sufficient to cover all operating expenses proposed. There has never been an issue with being able to identify the necessary talent that is needed for our organization’s growth. The issue has been the ability to compensate said persons accordingly. Yes, the funding will be useful to build upon what we have started but it will also take much more additional funding to achieve a full staff and sustainability.

Equitable development — “public and private investments, programs and policies in neighborhoods that meet the needs of residents, including communities of color, and reduce racial disparities, taking into account past history and current conditions” (Curren et al., 2016, p. 1) — is essential to addressing needs among startups created by journalists of color. As the respondent notes, the problem isn’t human capital, it’s access to sufficient financial capital in order to pay people for their work. Perceptible inequality isn’t limited to who receives funding — it also poses problems of how to use said funding. When startup founders are attempting to address day-to-day needs, they are unable to dedicate themselves to projects that take a significant investment of time, such as investigative work:

If we were to receive a significant amount of funding at one time, we will be able to be sure that we will have funds in the bank to pay salaries and other operating expenses that are crucial to maintain our news organization functioning well. … Instead of focusing all the time in raising funds to keep our lights on, we will focus on finding ways to produce more high-quality journalism on an everyday basis, do more enterprises and investigative reports to respond to the news and information needs of our audience.

These comments lead us to conclude that without sufficient financial backing from funders and/or advertisers, startup news organizations become another realm for wage inequality along racial and ethnic lines. Additionally, the piecemeal approach of small grants can sometimes contribute to a perpetual cycle of performing productivity rather than providing sufficient support for publishers to dedicate adequate time to actually producing and distributing the news, a theme we discuss more in the next section.

How Grant Reporting Drains Resources

As part of the “coping with scarcity” theme, we also include comments that reference how qualification demands (in accelerator programs, training, reporting requirements, and the like) create conditions of scarcity in terms of time/human resources. As several respondents noted, completing tasks related to reporting on the funding sources often detracted from the work the publications were ultimately able to do. One comment from a respondent provided a point-by-point articulation of this reality:

We’re better off in that the funding allows us to continue operations, but what would be better than stretching limited staff even thinner would be general operating funds to hire an additional employee who could make the most of the accelerator training. Our organization has participated in two accelerator programs that, on balance, required far more of our small team than the relatively small amount of money was worth. For example, in one instance my team spent more than 60 hours writing and rewriting a single interim grant update because the funder did not know what it wanted and kept changing the requirements.

Another respondent further operationalized the time/money/experience equation in their critique of an accelerator program. Such initiatives are again reminiscent of a type of benevolence that assumes deficiency rather than identifying and supporting assets among recipients (Gladden & Daniel, 2022):

I gained valuable information and a wider network and some funds to pay certain expenses (less than $5,000). However, I do wonder if I would have been better off using the nine weeks to listen to readers and bank a bunch of stories. It’s the reporting that has the real value. After posting several stories, the accelerator folks would have had more meat on the bones to react to and help mold into the next phase. The funding was so far below what I expected that I am now spending huge amounts of time searching and applying for money as well as writing a backlog of stories. I’m exhausted and wished I had saved my energy for either solo-reporting or finding money to pay a freelancer.

This respondent seems to suggest that while the accelerator program did allow them to navigate some of Dorsey et al.’s (2020) “barriers to funding,” namely getting connected, building rapport and securing (initial) support, the time value of the small grant creates sunk cost in comparison to spending the time doing actual reporting. Their conclusion, “I wish I had saved my energy,” suggests that the funding had an inverse impact and actually reinforces the fourth obstacle, sustaining relationships. The frustration of having invested precious time for nominal support sours the respondent’s experience, which may in turn lead them to opt out of efforts and interventions. The respondents above note that funding is often not enough to make sustainable or short-term hires within a strategic plan that moves an outlet toward greater self-sufficiency, the ideal end goal for philanthropic investment as intervention. Another counters that their inability to apply for similarly limited funding functions as a de facto means test:

I noted that accelerator requirements are overly burdensome not because I wouldn’t want my organization to participate in an accelerator but because to participate in them requires having staff members that can dedicate their time to it. … I’ve had to turn down — or have not been eligible for — many opportunities that I wish we could take advantage of (and that in some cases we’ve been specifically invited to apply for), including accelerators, reporting grants, collaborations, and business training — because we simply don’t have the staff. A grant of $10K or even $25K for a short-term program does not allow us to bring on staff to take advantage of that program. … While on the whole our org is better off after receiving funding, I’ve had to be more judicious about the funding we receive to make sure that is the case. Short-term grants, I’ve learned, can simply add to burnout, as it’s one more project — and potentially, one more part-time contractor — for a tiny team to manage. The catch-22 is that for many funders, having a moderate-sized team and a sizable budget is itself a prerequisite for funding.

Time is money and these insights illustrate how funders’ good intentions can actually compound founders’ troubles with maximizing access to both resources. This cycle is an example of what Morrison (1975) described as the function of racism: distraction that keeps marginalized folks from doing their work. While reporting requirements are arguably essential for foundations to track the impact of their investment, without a clear consideration of recipients’ contexts — particularly grantees’ time constraints — they can create obstacles that ultimately overwhelm publishers and their staff, causing them to question the true value of philanthropy.

The Upside: Self-determined Needs

Despite the perceived inequities in funding and feelings of scarcity, respondents reported that, on the whole, funding from philanthropic organizations had a positive impact on their operations. Broadly speaking, such investments help cover equipment, freelance/contract-based labor, and invest in training. Additionally, those who found the programming requirements “not very burdensome” or “not at all burdensome” identified intangible benefits — such as the ability to learn how to pitch to more/different funders, and recognizing the buy-in that comes from having a particular foundation’s support for their operations. A number of respondents also expressed gratitude for training on skills related to improving their capacity for fundraising. One respondent said that “the accelerator program we attended gave us a roadmap to avoid obvious mistakes,” while another said that the opportunities to connect with similar organizations was most useful. As another respondent said:

Things like training, and learning best practices from other BIPOC organizations, has been extremely important, and a learning lesson for us. We are learning that much smaller organizations are doing several things we aren’t doing, including digital wise. The money helps, but what we learn is just as important.

Across the board, BIPOC founders said what they need most from philanthropic organizations is sufficient funding to support capacity-building. Our close reading of their comments highlights this common theme, thus we present a roundup of comments salient to this theme that emphasize repetition of key terms like sustainability to underscore this need, before presenting our final analytic comments at the end of the section:

We are bootstrapping it — managing with volunteers and honorarium. We are unable to offer salaries and benefits.

We are getting a little bit here for reporting, a little bit there for digital development and sustainability, but together it doesn’t add up yet to make the hires we need to pursue our vision and achieve the work that funders want to support (and which is integral to raising more funds and building more funding strategies).

[We] Require a lot more funding to remain sustainable long-term.

We need more funding and we need more multi-year funding so we can plan better for the future.

We have one major funder who has consistently been a champion of our organization and has increased their grant each year. They generally meet one aspect of our primary need, however, the funds provided are only enough to keep us afloat in the same capacity. We need funding that allows room for growth and sustainability.

Journalists of color who move into entrepreneurship as digital publishers encounter “Silicon Valley Ideology” (Schradie, 2015, pp. 67–68) as another barrier to participation in both the news environment and philanthropic overtures specifically designed to support their projects. Such ideology assumes individuals are able to freely participate in democratic activities — including media-making — through digital media use. Yet these assumptions are based within the white racial frame, and ignore historically entrenched barriers to participation that still exist for those outside the dominating culture. And while digital technologies have and do offer those with access the ability to publish counter-hegemonic media narratives, as the subjects of this research aim to do — the assumption ignores the actual costs of participation. As Schradie warns: “people without resources fall through the digital cracks. The question is … who is left out?” (2015, p. 68). Our respondents’ stories are an indication not only of who, but also how. For our participants who have chosen to serve structurally marginalized audiences, certain prerequisites to securing adequate funding (i.e., having a particular number of staff; completing pre-validation processes) uphold exclusionary logic with consequential stakes. Philanthropic organizations have positioned themselves as consequential actors in newsmaking as an element of Western democratic processes. Through their financial influence, they replicate tests of worth for inclusion. Ultimately, journalists of color who must meet arbitrary thresholds for inclusion into their programs are inadvertently burdened by them, and those who do qualify are further taxed in terms of time as they re-certify their worthiness through reporting requirements. As our respondents note, some of these qualifications and reporting practices often outweigh the benefit of access to philanthropic funders, dollars, and other forms of support. Thus, ultimately, philanthropic organizations’ assumptions may actually do more to stymie participation than they do to encourage it.

Discussion

Our initial survey of BIPOC journalism entrepreneurs/founders maps a nationwide network of individuals and micro-organizations working to provide timely and relevant information to the communities they serve while attempting to garner sufficient resources to fund and power their endeavors. Philanthropic support is essential for these organizations, as BIPOC-led organizations — of any kind — receive less than 1% of all funding provided by venture capital (Houser & Kisska-Schulze, 2022), have been historically passed over and are now competing against tech giants for advertising revenue (Bora, 2022), and share in mainstream media’s struggles to attract paying subscribers to support their products (Chen & Thorson, 2021). Yet philanthropy has long struggled with racial disparities of its own, including the creation and maintenance of structural barriers to inclusion that leave BIPOC-led organizations out of critical decisions about which projects to fund, at what level, and for how long (HoSang, 2014). BIPOC founders seeking institutional support find themselves at the crux of these problems, even as they look toward an industry that has again pledged to recommit itself to racial justice work. This study begins to address the need for data that makes the reality of insufficient funding mechanisms legible to foundations so that they might reconsider their approaches to supporting BIPOC-led news organizations, as well as to BIPOC journalism entrepreneurs themselves, giving them insight on some of the difficulties that lie just beyond an initial influx of philanthropic cash.

Our research assumes a sousveillant position to assess the impact of philanthropy as an intervention in the health and sustainability of ethnic news media. The responses indicate that BIPOC-led news organizations are keenly aware of how they are being positioned in the reputation management schemes of philanthropic organizations attempting to engage in racial justice work through their donations. Our results indicate that the ethnic news media outlets represented by the BIPOC founders who responded to the survey are effectively instrumentalized by foundations (Yu, 2016). As stakeholders in the broader news media ecology, foundations are able to use the visibility of their grants and gifts to ethnic news media to advance their own agendas of engaging in anti-racist work, even if the donations are not substantial enough to truly meet the outlets’ needs (Bora, 2022). These actions ultimately create unfavorable conditions for BIPOC journalism entrepreneurs, who recognize the inequalities between their operations and those founded and run by non-POC journalists. Further, the requirements for funders to undergo extensive training and reporting as a condition of receiving microgrants creates a double burden for these journalists, many of whom are often working as single owner-operators or supervising a bare-bones staff and have little time to dedicate to these revenue-generating activities.

Although BIPOC founders recognize the rationale behind specific reporting requirements, foundations and other funding organizations should carefully examine these stipulations to determine whether these demands are proportionate to their perceived benefit. The overwhelming responses about a need for substantial support in the means of operational capital suggests that small, project-size grants may have an unintended consequence of extracting labor that detracts from the news outlet’s actual mission, which can negate the funder’s intended impact. If funders are unable to provide larger, more sustainable awards that actually meet the expressed needs of funders, they may consider reconfiguring their own teams in order to provide material support for collecting and analyzing the data they request from the outlets they aim to support. These findings are important because they underscore the undervaluing and underfunding of community news outlets that provide critical news and information to persistently underserved communities. These findings also highlight the hurdles BIPOC news outlets face, even for small amounts of money that impart more harm than help to communities and news organizations led by and for people of color.

Notes

1 LatCrit is a complement to Critical Race Theory developed from Latinx perspectives. It holds similar goals to CRT while challenging the Black-White binary through which CRT was developed. See: Elizabeth M. Iglesias, International Law, Human Rights, and LatCrit Theory, 28 U. MIAMI INTER-AM. L. REV. 177-213 (1997).

References

Bird, M. D., & Aninat, M. (2022). Inequality in Chile’s philanthropic ecosystem: Evidence and implications. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-022-00541-z

Bora, M. (2022). Show me the money: BIPOC media still waiting on ad spend. WURD. https://wurdworks.com/show-me-the-money-bipoc-media-still-waiting-on-ad-spend/

Bonilla-Silva, E. (1997). Rethinking racism: Toward a structural interpretation. American Sociological Review 62(3): 465–480.

Browning, J. G. (2022). Should legal writing be woke? Scribes Journal of Legal Writing, 20, 25–50. https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/scrib20&div=6&id=&page=

Bunce, M. (2016). Foundations, philanthropy and international journalism. Ethical Space: The International Journal of Communication Ethics, 13(2/3), 6–15.

Carlson, M., & Usher, N. (2016). News startups as agents of innovation. Digital Journalism, 4(5), 563–581. DOI:10.1080/21670811.2015.1076344

Carvajal, M., García-Avilés, J., & González, J. (2012). Crowdfunding and non-profit media. Journalism Practice, 6(5-6), 638–647. DOI:10.1080/17512786.2012.667267

Chen, W., & Thorson, E. (2021). Perceived individual and societal values of news and paying for subscriptions. Journalism, 22(6), 1296–1316. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884919847792

Clark, B. (2022). Journalism’s racial reckoning: The news media pivot to diversity. Routledge.

Collins, P. H. (1993). Toward a new vision: Race, class, and gender as categories of analysis and connection. Race, Sex & Class 1(1): 25–45.

Costa, C. T. (2013). A business model for digital journalism: How newspapers should embrace technology, social and value-added services. Columbia University Journalism School.

Curren, R., Liu, N., Marsh, D., & Rose, K. (2016). Equitable development as a tool to advance racial equity. Othering & Belonging Institute. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/62d1511d

Cyril, M. D., Kan, L. M., Maulbeck, B. F., & Villarosa, L. (2021). Mismatched: Philanthropy’s response to the call for racial justice. Philanthropic Initiative for Racial Equity.

Diaz, H. L. (2023). LatCrit: Where is the Afro in LatCrit? Journal of Latinos and Education. DOI:10.1080/15348431.2023.2180364

del Peon, G. (2021). Philanthropy- and community-launched startups tackle news deserts. NiemanLab. https://www.niemanlab.org/2021/12/philanthropy-and-community-funded-startups-tackle-news-deserts/

Deo, M. E. (2021). Why BIPOC fails. Virginia Law Review Online, 107, 115–142. https://www.virginialawreview.org/articles/why-bipoc-fails/

Deuze, M. (2006). Ethnic media, community media and participatory culture. Journalism, 7(3), 262–280. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884906065512

Dorsey, C., Kim, P., Daniels, D., Sakaue, L., & Savage, B. (2020). Overcoming the racial bias in philanthropic funding. Stanford Social Innovation Review. https://ssir.org/articles/entry/overcoming_the_racial_bias_in_philanthropic_funding

Ekdale, B. (2021). Engaging the academy: Confronting Eurocentrism in journalism studies. In V. Bélair-Gagnon & N. Usher (Eds.), Journalism Research That Matters (pp. 179–194). Oxford Academic.

Feagin, J. R. (2013). The white racial frame: Centuries of racial framing and counter-framing. Taylor & Francis Group.

Foss, N. J., Klein, P. G., & Bjørnskov, C. (2019), The context of entrepreneurial judgment: Organizations, markets, and institutions. Journal of Management Studies, 56(6): 1197–1213. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12428

Gladden, S. N., & Daniel, J. L. (2022). The plantation’s fall and the nonprofit sector’s rise: Addressing the influence of the antebellum plantation on today’s nonprofit sector, Administrative Theory & Praxis, 44(2), 123–132. DOI:10.1080/10841806.2021.1959167

Golebiewski, M., & boyd, d. (2019). Data voids: Where missing data can be easily exploited. Data & Society.

Gonzalez, J., & Torres, J. (2012). News for all the people: The epic story of race and the American media. Verso Publishing.

Harlow, S., & Chadha, M. (2019) Indian entrepreneurial journalism. Journalism Studies, 20(6), 891–910. DOI:10.1080/1461670X.2018.1463170

Heft, A., & Dogruel, L. (2019) Searching for autonomy in digital news entrepreneurism projects. Digital Journalism, 7(5), 678–697. DOI:10.1080/21670811.2019.1581070

HoSang, D. (2014). The structural racism concept and its impact on philanthropy. Philanthropic Initiative for Racial Equity: Critical Issues Forum, 5.

Houser, K., & Kisska-Schulze, K. (2022). Disrupting venture capital: Carrots, sticks and artificial intelligence. U.C. Irvine Law Review (2023 Forthcoming). http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4050585

Huffman, M. L., & Cohen, P. N. (2004). Racial wage inequality: Job segregation and devaluation across U.S. labor markets. American Journal of Sociology, 109(4), 902–936. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/378928

Iglesias, E. M. (1997). International law, human rights, and LatCrit Theory, 28. U. Miami Inter-Am. L. Rev. 177–213. https://repository.law.miami.edu/umialr/vol28

Leong, N. (2013). Racial capitalism. Harvard Law Review, 126, 2151–2226.

Malagon, M. C., Huber, L. P., & Velez, V. N. (2009). Our experiences, our methods: Using grounded theory to inform a critical race theory methodology. Seattle Journal of Social Justice, 8(1): 253–272. https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/sjsj/vol8/iss1/10

Mann, S., & Ferenbok, J. (2013). New media and the power politics of sousveillance in a surveillance-dominated World. Surveillance & Society, 11(1/2): 18–34.

Miel, P., & Faris, R. (2008). A typology for media organizations. Berkman Center for Internet and Society at Harvard University. https://cyber.harvard.edu/sites/cyber.law.harvard.edu/files/Typologies_MR.pdf

Morrison, T. (1975). A humanist view. Portland State University.

O’Brien, D., & Wellbrock, C. (2021). How the trick is done—Conditions of success in entrepreneurial digital journalism. Digital Journalism. DOI:10.1080/21670811.2021.1987947

Porlezza, C., & Splendore, S. (2016). Accountability and transparency of entrepreneurial journalism. Journalism Practice, 10(2), 196–216. DOI:10.1080/17512786.2015.1124731

Ray, V. (2019). A theory of racialized organizations. American Sociological Review, 84(1), 26–53. https://doi-org.ezproxy.neu.edu/10.1177/0003122418822335

Risam, R., Santana, C., Vincent, C., Lynch, C., Reiff, J., Gonsalves, J., Unus, W., Bellinger-Delfeld, D., & Jackson, A. (2022). Confronting the embedded nature of whiteness: Reflections on a multi-campus project to diversify the professoriate. Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice, 22(7), 69–83. https://articlegateway.com/index.php/JHETP/article/view/5271

Rosenstiel, T., Buzzenburg, W., Connelly, M., & Loker, K. (2016). Charting new ground: The ethical terrain of nonprofit journalism. American Press Institute. https://www.americanpressinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/The-ethical-terrain-o f-nonprofit-journalism.pdf

Royster, D. (2003). Race and the invisible hand: How white networks exclude black men from blue-collar jobs. University of California Press.

Said, E. (1978). Orientalism. Random House.

Saldaña, J. (2009). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage Publications Ltd.

Sandberg, B. (2019). Critical perspectives on the history and development of the sector in the United States. In A. M. Eikenberry, R. M. Mirabella, & B. Sandberg (Eds.), Reframing nonprofit organizations (pp. 26–37). Melvin & Leigh.

Schiffrin, M. (2019). Fighting for survival: Media startups in the Global South. Columbia University SIPA. https://www.cima.ned.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/FightingForSurvival_March_2019.pdf.

Schumpeter, J. A. (1934). Theory of economic development: An inquiry into profits, capital, credit, interest, and the business cycle. Harvard University Press.

Schradie, J. (2015). Silicon Valley ideology and class inequality: A virtual poll tax on digital politics. In S. Coleman & D. Freelon (Eds.), Handbook of digital politics (pp. 67–84). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Sewell, W. H. (1992). A theory of structure: Duality, agency, and transformation. American Journal of Sociology 98(1):1–29.

Steininger, D. M., Brohman, K. M., & Block, J. H. (2022). Digital entrepreneurship: What is new if anything? Business Information Systems & Engineering, 64, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12599-021-00741-9

Tameez, H. (2022). American journalism’s “racial reckoning” still has lots of reckoning to do. NiemanLab. https://www.niemanlab.org/2022/03/american-journalisms-racial-reckoning-still-has-lots-of-reckoning-to-do/

Usher, N. (2017). Venture-backed news startups and the field of journalism. Digital Journalism, 5(9), 1116–1133. DOI:10.1080/21670811.2016.1272064

Usher, N., & Kammer, A. (2019). News startups. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.827

Villanueva, E. (2021). Decolonizing wealth: Indigenous wisdom to heal divides and restore balance. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Wagemans, A., Witschge, T., & Deuze, M. (2016). Ideology as resource in entrepreneurial journalism. Journalism Practice, 10(2), 160–177. DOI:10.1080/17512786.2015.1124732

Wallace, L. R. (2019). The view from somewhere: Undoing the myth of journalistic objectivity. University of Chicago Press.

Wright, K., Scott, M., & Bunce, M. (2019). Foundation-funded journalism, philanthrocapitalism and tainted donors. Journalism Studies, 20(5), 675–695. DOI:10.1080/1461670X.2017.1417053

Yu, S. S. (2016). Instrumentalization of ethnic media. Canadian Journal of Communication, 41, 343–351.

Yu, S. S. (2018). Multi-ethnic public sphere and accessible ethnic media: Mapping online English-language ethnic media. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44(11), 1976-1993, DOI:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1346466

About the authors:

Meredith D. Clark, Ph.D. (@MeredithDClark; she/her/hers), is an associate pro-fessor in the School of Journalism and the Department of Communication Studies at Northeastern University, where she also serves as director of the Center for Communication, Media Innovation and Social Change. Her research focuses on the intersections of race, media and power. Her first book, We Tried to Tell Y’all: Black Twitter and Digital Counternarratives is forthcoming from Oxford University Press.

Tracie Powell is the founder of The Pivot Fund, which seeks to support independent BIPOC community news. Powell is immediate past chair of LION Publishers, a professional journalism association for independent news publishers. She was founding fund manager of the Racial Equity in Journalism (REJ) Fund at Borealis Philanthropy and a 2021-2022 Shorentein Center Research Fellow at Harvard University. She was a senior fellow with the Democracy Fund and was a 2016 JSK (Knight) Fellow at Stanford University. Powell is a graduate of Georgetown University Law Center and The University of Georgia’s Henry W. Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication.