Mixing the old with the new through digital media: How young Cuban journalists navigate a changing Cuba

By Shearon Roberts

[Citation: Roberts, S. (2019). Mixing the old with the new through digital media: How young Cuban journalists navigate a changing Cuba. #ISOJ Journal, 9(1), 29-48.]

This mixed method study examined how young Cuban journalists use both traditional and digital media to engage discourse on a changing Cuba. Firstly, this study examined interviews with 35 Cuban journalists at nine media organizations in Cuba. The findings indicated they do report on critical issues in their traditional media jobs in ways that are tolerated under the limitations to freedom of the press. Secondly, this study examined 194 articles published by these journalists on independent digital platforms. Online spaces provided young Cuban journalists the opportunity to publish critical-constructive discourse on a range of topics. The study supports that both traditional and online platforms can work together to sustain the coverage of critical social issues in places where full freedoms for the press are limited.

In a “Note to the Censor,” Cuban online magazine El Estornudo notified local readers that access to the magazine’s digital platform was blocked in February 2018 by the Cuban government (de Assis, 2018). This form of recent censorship was not isolated as other prominent independent Cuban online sites like Diario de Cuba, CiberCuba and Café Fuerte were also blocked within the same year (de Assis, 2018). In a study of the 14 leading Cuban blog sites by Elaine Díaz Rodríguez, the founder of the Cuban blog Periodismo del Barrio, all of the leading sites have effectively been blocked or threatened to be blocked by the state in the past five years (Rodríguez, 2018).

In Cuba, content primarily accessed through digital platforms could face retribution from the state at any time. Therefore, this study seeks to examine how critical discourse appears in Cuba by different groups who work primarily in the media, and as journalists. This study therefore focuses particularly on younger Cuban journalists, who entered their profession after 2010, and who also engage in digital media platforms for journalism and civic discourse. The study seeks to understand attempts to bridge traditional practices of journalism in Cuba with experiments in media opening exemplified through the work of the more prominent Cuban bloggers. A generation of reporters have now come of age in the past 15 years since Cuban bloggers began their experiment with tolerated, and in some cases, repressed, forms of alternative journalism. Trained in traditional university communication programs, these recent graduates often begin their careers in state-run media organizations in Cuba. However, unlike journalists prior to the 2000s, they have begun their careers at a time of access to digital platforms. The work of early Cuban blogs demonstrated the potential of online platforms for practicing their craft, and engaging topics of concern to their generation. However, the predominant consumers of the leading 14 Cuban blogs remains audiences outside of Cuba. Therefore, this study examined how current Cuban journalists combine the use of digital platforms, in addition to working in traditional media, to primarily engage audiences in Cuba, and not outside of Cuba. It seeks to ask if there is a space to mix both the old journalistic traditions, with newer ones, in tolerable ways, that avoid the threats of censorship, and allow newer entrants into the profession to pursue careers as journalists in Cuba.

Impact of Cuban Blogs on New Journalists

The experiences of early Cuban bloggers inform the attitudes by younger journalists in this study about the potentials of digital spaces for media discourse. Since 2001, Cuban blog sites have flourished with over half having news operations outside of the country (Rodríguez, 2018). For younger Cuban journalists in this study, limited access to external support networks means they must rely on their jobs in state-run media for their livelihood. To date, scholars count dozens of Cuban blogs that span all topics from politics to culture. Rodríguez (2018) identifies 14 sites, noted for their critical work, and recognized for their journalism standards. This study examined how alternative journalism encourages younger Cuban journalists to push to expand what they cover in both traditional and digital spaces. The majority of the 14 leading Cuban blog sites, Rodríguez (2018) notes, were created after 2014. Yet Internet access for Cubans ranges from 5% to 30%, according to Freedom House estimates, and remains controlled by the Cuban government (Kahn, 2017). Furthermore, Rodríguez (2018) estimated that Cubans on the island only make up the primary source of traffic for less than half of the 14 sites. This study therefore asks how the use of digital platforms, by younger journalists who work in Cuba, can support new discourse for audiences at home.

Therefore, the purpose of this study is not to examine these leading 14 sites and their content, as other scholars have already done (Firchow, 2013; Henken, 2011; Henken & Porter, 2016; Henken & van de Voort, 2014). This study looks precisely at how the presence of major Cuban blogs impacts the practices of journalism by young Cubans who work in legacy and sometimes state-run traditional media. This question remains relevant because the leading sites continue to face the risks of censorship, once Cuban state agencies block domestic access to them. Additionally, the ability of these sites to disseminate among Cubans able to afford access to El Paquete Semanal(1) or through email access, puts additional constraints on the current distribution model, once access is blocked by the state.

This study examines how over a decade of a form of journalism experimented through Cuban blogs widens the possibilities of practice for a new generation of journalists in Cuba. In this case, this study describes how young Cuban journalists, who still continue to work in traditional media like state-run newspapers and magazines (old), attempt to transform practices that hybrid the new (digital) and the old, to impact local discourse in media spaces primarily intended for all Cuban audiences. Therefore, this study seeks to evaluate two effects for younger journalists. How has an era of Cuban blogging shaped their understanding of journalism? And secondly, how has an era of Cuban blogging shaped the types of stories and social discourse they choose to report on to local audiences. Media opening has allowed younger Cubans to practice a form of journalism that is “in between,” capable of both introducing new discourse within traditional outlets, but also using online media platforms to further the conversation.

The practice may seem less radical in comparison, but the aim and objective are a form of agency from within, knowing that a free press in Cuba is still much further off, but that vital conversations could continue to take place, even in more traditional spaces.

A Changing Cuba

In April 2018, Cubans for the first time in roughly 60 years had a president whose last name was not Castro. The direction of the nation was transferred to the hands of the country’s new leader Miguel Díaz-Canel Bermúdez, who was born in 1960, a year after the Cuban Revolution. Cubans had already experienced incremental social and political changes since 2006, when Raúl Castro succeeded his brother Fidel Castro’s 50-year-run leading the state. Raúl’s tenure as head of the country brought political changes (term limits) and economic changes (private enterprise) that impacted social outcomes.

These current changes, as Cuban scholar Miguel Angel Centeno (2004) suggested, should be examined within “the limits on both Cuban exceptionalism and the constraints on change in Latin America” (p. 404). The 40 years of Cuban history after 1959, Centeno explained, meant that Cuban society and structure varied from the rest of Latin America and the Caribbean. Cuba differed mostly from its neighbors particularly for its resistance of neoliberalism, reinforced by the Castro regime. Now, Centeno wrote, scholars must acknowledge that the exceptionalism of Cuba has begun to erode, as both migration and remittances are contributors to inequality. Who has access to remittances in Cuba determines social mobility resulting in widened “racial stratification” that Centeno described as resembling an “economic apartheid” (2004, p. 404). The influence of “neoliberal ethos” through the rise of informal commerce in Cuba today, Centeno noted (2004, p. 404), means social conditions in Cuba are now more closely resembling those of its Latin American neighbors.

The 10 years of Raúl Castro’s policies also coincided with a rise in Cuban blogging that, in many cases, were alternative, critical voices on a changing Cuba (Henken, 2011; Kellogg, 2016; Rubira & Gil-Egui, 2013; Vicari, 2014). A number of the original Cuban bloggers were part of social and or intellectual movements, and not altogether, necessarily trained traditional journalists (Henken & van de Voort, 2014; Timberlake, 2010; Venegas, 2010; Vicari, 2015). More importantly, the Cuban government has tolerated the work of Cuban bloggers, although blocking sites and surveillance is the primary form of retribution (Kahn, 2017).

Since the first wave of Cuban bloggers are both a mix of journalists and activists, this study looks at younger journalists trained in traditional journalism in Cuba. This newest cadre of young Cuban journalists has now entered the field, however their training and careers began in the wake of the work of the original wave of Cuban bloggers. Likewise, these recent entrants to journalism were schooled to begin careers in more censored, and self-censored, state-run media outlets. This study therefore identifies how this second wave of media professionals wrestle with the tenets of journalism—the desire to investigate and to report truths—with the realities of working in the media with social and political constraints of state and self-censorship, on their practice (see also Henken & Porter, 2016).

The rise of Cuban blogging has also problematized the tenets of journalism. Western journalism upholds objectivity, facticity, detachment, and non-partisanship as liberal models of journalism that distinguish it from more state-controlled practices of the profession, as is the Cuban case (Lawson, 2002). However, in 2009, Spanish newspaper El País, named Cuban blogger Yoaní Sánchez, the founder of Generación Y, as its Havana correspondent. The paper described Sanchez as “a Cuban journalist” who would “provide the reader with a more balanced view of reality” (Lamrani, 2015, p. 83). Sanchez’ positions, Lamrani noted, have been strongly in opposition to the Cuban government and have sided with U.S. diplomats in Cuba. In upholding “plurality,” Lamrani wrote that in this instance, El País, should have also provided the reader with a “blogger who supports the revolutionary process” (2015, p. 83). The paper’s previous correspondent in Havana, Mauricio Vicent, ironically noted the pressures of covering Cuba for a foreign media source, acknowledging years of self-censorship. Lamrani wrote that Vicent confided in a colleague that “if one day I were to write something positive about this country, they would fire me without hesitation” (2015, p. 13).

This observation by Vicent, a Cuban-raised but Western-employed journalist underscores that when it comes to Cuba, both journalists operating with or without the constraints of censorship, self-censor. Likewise, the case of Sanchez’ endorsement by a Western media outlet demonstrated that liberal media organizations also forgo notions of impartiality in presenting a Cuban reality. Furthermore, defining the “Cuban reality” differs depending on who is asked. Even among contemporary journalists, Sara García Santamaría (2017, p. 5) noted that Cuban journalists often contradict each other in articulating discourse about the Cuban people. More importantly, Santamaría’s examination of discourse within state-run Granma, up to 2011, showed “a great degree of anti-status-quo sentiment” (2017, p. 6).

The search for the balance of a mix between traditional practices of journalism and new ones, is the current Cuban journalist’s experiment. In media, as it is in Cuba’s politics, society, and economy, this exercise is no different. This study therefore builds on this original body of scholarship on Cuban bloggers and Cuban media discourse, by examining specifically traditionally trained, millennial media professionals, who practice journalism on both print and digital platforms in Cuba. Through traditional print platforms, these young media professionals are able to practice relatively tolerated modes of critical-constructive public discourse and commentary that allowed them to be paid and accepted within the profession, and among professionals at state-run media. Digital platforms then provide the space for expanding journalism practices, in search of “truth-telling” that deconstructs a changing Cuba, in an age of shifting relations with the United States.

This study therefore examined how digital media platforms can serve as intermediary spaces for practicing journalism for Cuban media professionals who still desire to work in traditional media spaces. The collective use of online platforms creates digital echo chambers, where discourse can then be reintroduced into traditional platforms, as a result of the digital chatter. Therefore, external digital platforms become the agenda-setting spaces for social and political discourse that would typically have been self-censored when producing content for traditional platforms. Engaging the digital “chattersphere” therefore allows young Cuban professionals to mix the old and the new, in ways that make critical discourse mainstream and that works to fold the Cuban bloggersphere back into mainstream platforms. This hybrid allows journalists in Cuba to harness blogging for work they wish to engage with Cuban audiences, on traditional, state-run platforms.

Non-Traditional Media Opening

While Cuba’s recent history differs from Latin America in some ways, as Centeno (2004) notes, current changes in Cuba echo shifts that occurred elsewhere in the Americas. The use of Cuban blogs should be examined as part of the theoretical concept of media opening. Media opening is the process to which media systems in non-democratic or authoritarian societies become more free. Scholars like Lawson (2002), Hughes (2006) and Porto (2012) have looked at how media systems in Latin American nations have experienced media opening. Lawson (2002) argued that political liberalization contributes to the opening of the press in Latin America. However, Hughes (2006) also credits the rise of civic-minded, alternative news organizations in Mexico as contributing to media opening there, long before political changes are complete. Porto (2012) found that for Brazil, even newly privatized media conglomerates contributed to media opening by shifting coverage in response to changing public opinion, which acts as a form of consumer demand. In Central America, Rockwell and Janus (2010) cautioned that even democratization does not automatically translate to more press freedoms. When media systems are concentrated in the hands of a small group of elites, news discourse amplified right-leaning political beliefs that reinforce policies that favor the top 1% (Rockwell & Janus, 2010).

These instances of media opening do not entirely fit the current Cuba case. However, media opening in Haiti provides more in common with Cuba as it currently unfolds, than do the other examples of media opening. In Haiti, for roughly three decades, media censorship existed under the Duvalier dictatorship. It began first in 1957 under François “Papa Doc” Duvalier and then under his son Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier, who held power until 1986. Like Cuba, independent media in Haiti in this period was tolerated, and in some cases allowed to flourish. Likewise, both state censorship and self-censorship occurred in Haiti during this time. In Cuba, it is blogs that are now tolerated. In the Haitian case, radio was then the new medium. Radio under dictatorship in Haiti became, and now remains, the dominant platform for news, commentary, social discourse, and information. Led by Radio Haïti Inter, Haiti’s first independent radio station, Jean Dominique and his wife Michele Montas-Dominique fostered the station’s critical journalism from 1968 onwards (Montas-Dominique, 2001). Stations like Radio Haïti Inter were important because they operated at home, at a time when many journalists had left the country, and set up diaspora media abroad, where Haitians at home were not the primary audience. Radio in Haiti during this period reached domestic audiences providing media discourse that was critical of the status quo. In a sense, Haitian expat media during the dictatorship mirrors the more prominent Cuban blogs that now carry larger external audiences, and are situated further in proximity and accessibility to citizens at home.

To maintain critical discourse and to continue broadcasting to citizens, Radio Haïti Inter deployed several strategies that allowed them to continue their work under the confines of censorship. These strategies ranged from covering human rights movements in other countries in the region, and even in South Africa (Wagner, 2017). By using external news and newsmakers that reflected the efforts of the rights of peoples outside of Haiti, Radio Haïti Inter indirectly did the work of democratic and civic education, without always having to directly address the lack of freedoms at home (Montas-Dominique, 2001). This is not to say that direct critical discourse of the government did not exist at the time, it certainly did. However, the work of civic education, within the confines of an authoritative state, required more nuanced approaches by Haitian journalists under Duvalierism, in order to continue to practice their craft at home. This strategy early on gave news organizations the space to conduct media literacy through covering external events that ultimately educated citizens of the pursuit for freedoms elsewhere, underscoring the lack of freedoms at home.

Even more traditional media spaces in Haiti adopted similar approaches. Haiti’s newspaper of record, Le Nouvelliste, also pursued a strategy of self-censorship during the dictatorship and survived because of this (Roberts, 2016). However, as Radio Haïti Inter’s coverage increasingly addressed instances of oppression in the country, the state shut down the news station twice and forced its owners in exile (Montas-Dominique, 2001). In 2000, the station’s founder Jean Dominique and a colleague were assassinated. By this time, the station had paved the way for more domestic journalists, and even those in more traditional newsrooms, to continue the work of critical journalism.

Media opening in Haiti included a combination of the work of critical discourse by native journalists positioned abroad, and a mix of strategies to achieve critical discourse by journalists based in the country. These tactics ranged from using the new media at the time to create new spaces for discourse, producing reportage that could be tolerated by the regime, but that served the larger goal of civic education, and by challenging the status quo by introducing discourse about similar injustices and forms of oppression elsewhere. In covering external movements, and by interviewing and featuring external activists, Haitian journalists at the time used a form of diversion that skirted censorship and indirectly hinted to the lack of freedoms at home (Wagner, 2017). The journalistic tactic here was that in covering foreign fights for freedoms, Haitians in turn became engaged in their own lack of rights and oppression at home.

This approach to media opening in Haiti during a dictatorship provides a lens with which to categorize how journalists in Cuba, who wish to continue to work at home, in traditional or independent media, pursue “truth-telling” under confines to freedom of the press. The Haitian example therefore bears a closer resemblance to approaches to media opening in Cuba that this study aims to explore with a specific study of young Cuban journalists.

Firstly, there is external, critical journalism, and the dominance of a new, less hegemonic media platform. In the Haitian case, there was the growth of expat/exile media and the local rise of radio. In the Cuban case, these are Cuban blogs that while read in Cuba, carry a larger production, distribution and consumption base outside of the country (Rodriguez, 2018). Yet in Cuba, digital technology allows for the dissemination of new media content, and the use of social media platforms. Secondly, state censorship is enforced, and in-turn, media organizations in the country actively self-censor. This was the case for Haiti, particularly for print and state-owned media, as it is the case for state-run media and some independent media in Cuba. Thirdly, Haitian journalism even amidst forms of censorship still actively covered social and political issues that were critical of the status quo, but did so in ways that spotlighted resistance, without always directly having to openly challenge regimes. As Santamaría’s examination of Granma shows, challenges to the status quo also appears in traditional media in Cuba (2017, pp. 186-187). These similarities can be reflected in how journalists, still in Cuba, engage in digital spaces, but continue to work in traditional spaces to practice journalism within confines of the existing political climate.

This study argues that this tactic employed by younger Cuban journalists mirrors the measured liberalization within the political and economic realm, but more so in the economic realm in Cuba today. It does not completely do away with state controls of sectors, in this case, state control of media and freedom of speech. However, new platforms allow the media to move the needle and to test the state threshold for acceptable internal debates, as outside influences inevitably change the nature of Cuban socialism. As the Cuban media professionals in this study outlined, these debates are not to call for the end of socialism, or for drastic changes to any positive, sustainable impacts of socialism that make Cuba unique, but to debate how the country can maintain some of the old (successes of the Revolution), by integrating the new (Cuban development in a twenty-first century global world) for the benefit of all Cubans.

Methodology

“It is the first time in my lifetime we will not have any of the heroes of the Revolution as president,” one female Cuban journalist, 26, shared during a field interview in 2017. A new generation of Cuban-trained media professionals are using new media to have external and internal dialogues about this new Cuba. The work of more prominent Cuban bloggers such as Yoaní Sánchez and Elaine Diaz Rodiguez have paved the way for early use of digital media platforms for freedom of expression in Cuba (Loustau, 2011; Miranda, 2016). However, it was met with state retribution for this group (Firchow, 2013). This mixed-method study included interviews with young Cuban journalists and a content analysis of a sample of the digital content they produce.

Sample

The purpose of this study was to examine Cuban-trained journalists who still work for state-run or independent media outlets in Cuba, but who also, simultaneously operate or contribute to digital media platforms. This study is based on interviews conducted in 2017, in person in Cuba, with follow up through written correspondence in 2018, when needed, after interviews were transcribed and translated. The study sample includes interviews with 35 Cuban journalists under the ages of 28, from nine media organizations. Within this sample, all 35 journalists were formally trained in university communication programs in Cuba, and all have worked as professional journalists in time spans ranging from one to five years. All of the journalists interviewed have completed stints at state-run media organizations, about one-third continue to do so, one-third work full-time in independent media, and one-third work part-time in independent media mixed with other communications and informal jobs. One-quarter of journalists in the sample either directly host their own blogs, and the remainder are contributors to other shared blog sites. Half of the journalists in this study are based in Havana, while the other half are based in other major cities in the country. One-third of the trained journalists in this group self-identify as Afro-Cubans. Given their current professional work, this study does not disclose information that identifies them or the places and spaces where their work appears.

This study sampled the types of media content young Cuban journalists created for digital platforms. These articles were shared directly with the researcher from blog sites, social media group posts, offline PDFs and via email. The sample articles were used to analyze the types of stories produced primarily for digital platforms, on the journalists’ own time, in 2017. Their digital content was either anonymous or published with pseudonyms. In providing the articles directly to the researcher, this allowed the study to verify that the articles were produced by young Cuban journalists, and to recover those that were offline PDFs shared through emails, and not readily available online. For the 35 journalists interviewed, each one shared 2017 digital content for this content analysis. On average some of the journalists produced digital content at least bi-monthly, while others were less frequent, posting once or twice, or every three to six months. In total, 194 digital articles were disseminated through digital platforms in 2017 that served as an additional space for their work being produced at more traditional media sites.

The interviews were transcribed and translated, when not in English.(2) Two coders organized interview responses into two main themes: a) attitudes toward journalism as an ideal; and b) strategies for practicing journalism in Cuba on a daily basis. The content analysis examined the types of platforms used for digital content, as well as the themes (topic) and framing (evaluative position) of the articles provided for the study. The coders marked each article using the title and lead paragraph to identify the theme. The coders used a coding sheet to note similar topics, and then grouped similar topics into related story topics.

To identify frames, the coders used two framing concepts (episodic and thematic frames). Episodic framing is discourse that presents information around specific events, while thematic frames provide discourse that examines issues not directly connected to a specific event but may stem from ongoing issues and events (Iyengar, 1996). The coders used both the lead (first paragraph) and nutgraph (context paragraph) of stories to determine framing approaches. For additional clarification, the coders continued reading the article until the framing approach was clearly identifiable in the article. Coding themes allowed the coders to analyze what types of issues these journalists used digital platforms to address. Coding frames allowed the coders to analyze how digital platforms expanded spaces for critical evaluation of the themes of the articles.

Results

In discussing how young Cuban journalists mix the old and the new, this study firstly outlines how they view their profession, and practicing journalism in Cuba. This study presents their insights, based on interviews, on their attitudes about the tenets of journalism, particularly at a time when anyone can blog, but not everyone may be considered a journalist. This study also summarizes their reflections on addressing subjects that are critical on social or political issues. Secondly, this study outlines strategies they have developed for practicing journalism in traditional spaces. Thirdly, this study presents the findings from coding the articles provided for the content analysis. This study then presents the major themes of the sample that demonstrate what issues these journalists addressed in 2017. It also summarizes what framing approaches were most prevalent among the sample. Lastly, it examines how different types of digital platforms were considered more convenient than others, for sharing content on varying subject matter.

Que es el “Periodismo Real”? What is True Journalism?

Perceptions on journalistic practice

In the words of one young, male journalist: “El periodismo real revela, investiga o enfada, lo demás no se que es” [“True journalism reveals, investigates and enrages, anything else, I don’t know what that is”] (personal communication, August 2, 2017). These are the words of a 26-year-old journalist who works primarily for an independent media organization, but who also produces content for a blog site he manages. He acknowledged that being able to achieve this form of “true journalism” “es una aspiración personal [is a personal goal].” His commitment to being able to practice journalism at its fullest “se debe perseguir hasta el cansancio [is what one must pursue tirelessly]” (personal communication, August 2, 2017).

In distinguishing activism from journalism, one female journalist, 25, who has worked in state-run media, distinguished that journalism is a form of civic engagement through truth-telling: “I have never been interested in becoming an activist because if you are neutral you can have a straight view of reality. If you are impartial, you can just write and be fair about what is going on” (personal communication, July 25, 2017).

Journalistic concepts like impartiality and fairness were also important to the work of presenting truths. The journalists interviewed in this study indicated that for their generation it was important to think critically about all possibilities for developing their state. The future of their country was not about being pro- or anti-state, pro- or anti-government. Rather, they saw their role in public discourse to fairly evaluate the status quo, to indicate what is working and to indicate what is not working in Cuban society.

“Mi generación es muy consciente del tiempo [my generation is aware of the times],” noted one male Cuban journalist, 23, who works for state-run media (personal communication, November, 23, 2017). They are educated on what the revolution has achieved, but they are also aware that for the country to move into the next era, the country would have to undergo gradual change. However, young Cuban journalists stated that any new changes must be mindful of what makes Cuba distinct, particularly in defying persistent challenges that many Latin American and Caribbean countries face. They believe this is also important in contextualizing discourse and telling truths.

According to a 26-year-old male Cuban journalist, who works for an independent media organization, “Our neighbors like Central America or Colombia or the Dominican Republic [have a lot of crime, violence and unrest]. We don’t want this for us” (personal communication, August 2, 2017). For Cuba to develop to become “a Norway,” a country he named, Cuba will need to begin to provide citizens “more rights” and revisit its laws.

Even evaluation of what has not worked since the Revolution is also part of truth-telling. One male Cuban journalist, 25, stated: “We are an underdeveloped country and our neighbors are not what we want to be. We want to keep our non-violent society, for example, in Central America it’s a very huge problem, but we want more freedom in individual issues like maybe to vote freely. So we want some changes, but we don’t want that those changes take us to a worse situation. We want changes, oh yeah, we want so many changes” (personal communication, August 2, 2017).

One female journalist, 27, who worked for state-run media, noted that “transparency” in the laws is needed. This can range from the process of voting for a president, to starting an enterprise, to even media laws. The same journalist noted that: “There are no cinema laws in movies, how to make movies, in an independent way, but there are for making movies for a state way” (personal communication, July 28, 2017).

Others emphasized that in their reporting, they highlight the importance of preserving access to basic services. The path to a more liberal and open Cuba does not necessarily mean less state control in some areas. One female reporter, 26, who worked for state-run media stated: “For example, water, it never would be privatized. Electricity, health, I don’t think those important services. They should be public. But I want a country where people could develop their own businesses and could be profitable” (personal communication, August 2, 2017).

Maintaining the standard of Cuba’s education is also important in their coverage in traditional media. One female reporter, 28, who works part-time for independent media, noted that education standards are at a disadvantage for younger graduates who must fill positions in teaching but lack the training to prepare Cubans for a modern, technology-driven digital world.

Likewise, since the ability to tap into the informal, private sector jobs are not equally distributed, some Cubans are able to invest in education by way of private tutors, who end up providing more advanced education for some, further undermining the equalizing impact of Cuba’s education system, according to this journalist (personal communication, August 2, 2017).

However, at the same time, a female reporter, 24, who works for state-run media, reinforced that coverage about education in Cuba also has to be fair. She noted that compared to the rest of the region and even in the United States, few countries excel in this area. “Education in Cuba is really good, we know it when we go outside the country, they say so” (personal communication, August 2, 2017). However, if the rise of private tutoring is not evaluated, she noted it can provide advantages for some who are able to afford it. It would also divert teachers away from dedicating to public education, because their livelihood can now benefit from private tutoring, at the expense of students who cannot pay privately for such services.

Strategies for navigating constraints

Young Cuban reporters outlined some tools they have adopted to operate within constraints of traditional media. The first is what can be described as discourse through acceptable outsiders. This involves featuring journalists, writers, and other public thinkers to be featured in interviews that allow these external voices to articulate resistance, struggle, oppression, and global change. In the Cuban context, such sources do not come from the West, particularly the United States, but from Latin America and the Caribbean.

One male reporter, 26, called this “Narrative journalism stories from across Latin America” (personal communication, November 24, 2017). These can be cultural stories that use resistance and movements, even literature, music, popular culture, and other art forms to speak about resistance. Young Cuban journalists said they often use these types of spotlights, features, Q&As and reflective essays that allow outsiders, within Latin America and the Caribbean, to talk about issues in their own countries that resonate with ongoing struggles in Cuba. These accepted outsiders are considered “safe” for traditional news outlets, because they shroud their work in performance or fiction.

One area in which young journalists said they explore critical voices comes from covering hip-hop and the re-emergence of Cuban “trovadores.” Trovas are native to Cuban culture, offering up social commentary and personal lived-experiences through music. However, the current resurgence of trovas, particularly from their own generation, young Cuban journalists noted, have become more political and socially critical in their music.

“Trovadores offer differing perspectives” and provide a good model for traditional journalism to balance and contextualize conflicting public opinion that Cubans carry about the status quo. As one male Cuban journalist, 27, who works for independent media stated: “Trovadores sing about whatever they want to sing about. Trovadores are not marionettes or puppets … the trovadores movements is one of the freest movements in Cuba, mas libres (he added in Spanish)…” (personal communication, November 24, 2017).

The social commentary of contemporary trovadores encourages civic dialogue on the evolution of Cuban institutions. In featuring the works and performances of trovadores, in stories about culture, young Cuban journalists said they are able to tap into diverse topics about politics and society indirectly through exploring the works of the performances and the art form itself.

A female Cuban journalist, 25, further explained in English that although state policy may perpetuate a singular view about a social issue, there is an active debate elsewhere in society about the status quo. “Here in Cuba, there is a false unanimity for all things that the government proposes. There is not in the parliament, no other ideas, just one, mostly, there is no other proposals than the government proposals” (she stated in English) (personal communication, November 24, 2017). The debates that trovadores raise in their music, she said, broaden the dimensions of how to insert alternative opinions into the public domain, in “safe” ways that allow journalists, like the trovadores, to be tolerated by the state for varying degrees of critical thought.

Another male reporter, 26, who works in independent media, described it as such: “There is debate in the city, not debate in the government” (personal communication, November 24, 2017). In using this “debate in the city” expressed through trovadores and their trovas, journalists write about these civil debates indirectly through spotlighting the artform. The focus then shifts away from whether government is open or transparent, to discourse that frames these cultural movements as representing and engaging the realities of Cubans. Young Cuban journalists present these social critiques through an artform as a way to examine existing social and political concerns but through softer news frames, like music and culture.

Other art forms also provide windows to capture resistance. One female Cuban journalist, 28, noted that Cuba experienced a renaissance for art in the 1980s. Since this period, a good number of this “generation of young artists … have left, a long and complicated story” (personal communication, July 31, 2017). Art has since returned as a medium for social critique, and as reporters they let their reports evaluate the messages of new forms of visual arts. In the past, she noted that forms of resistance also came through a ban on rock music. It was revived from the era when it was an underground culture, but now creates spaces to use music as anti-establishment.

In other ways, young reporters also are able to examine other social issues ranging from race to gender. For instance, stories of police profiling of Black people, particularly through the #BlackLivesMatter movement, serve as jumping points for journalism about issues of race and fairness. Young Cuban journalists, and not just Afro-Cuban journalists alone, said they have used reports from the United States to Brazil, to expose incidents of racism in Cuba. This type of coverage challenges the notion that the revolution automatically created a post-racial Cuba. As one Afro-Cuban female journalist, 23, who works in state media noted, the revolution did open doors for Black Cubans, particularly for those working in the media and in government (personal communication, July 29, 2017). However, racial profiling still persists in subtle and overt contexts for Afro-Cubans.

Lastly, young Cuban journalists said they examine generational change through their work. Where their parents may still tout the benefits of the revolution, they aim to outline how the revolution has become static.

According to one young male Cuban journalist, 26, “I think my generation, from my personal view, I think that we need another real revolution. The thing is that there is the status quo power and it’s like it’s so institutionalized that it not always responds to people’s needs” (personal communication, November 23, 2017).

Here, they have used external headlines to talk about the need to go beyond the existing status quo. One young female reporter, 24, noted that she used coverage of Venezuela’s turmoil in its elections after President Hugo Chavez died to identify that when policies have expired beyond their initial objectives, and are no longer sustainable, they trigger unrest. The Venezuelan 2015 elections were an opportunity for coverage in Cuban media of an outcome in a country that supported Cuban development but was either unable or unwilling to make political changes to adapt to economic setbacks. Again, this reporting did not address Cuba directly, but in covering Venezuela’s challenges, it caused reflection on the internal status quo. As the reporter noted this type of coverage was to “put this debate metaphorically to challenge people to consider these themes” (personal communication, July 27, 2017).

Content analysis of the use of digital spaces

The above strategies, outlined in field interviews in Cuba, were developed for practicing journalism at traditional news outlets and platforms. However, these young Cuban reporters also contribute to and produce content for digital platforms for engaging audiences more directly about a changing Cuba and the future of Cuba.

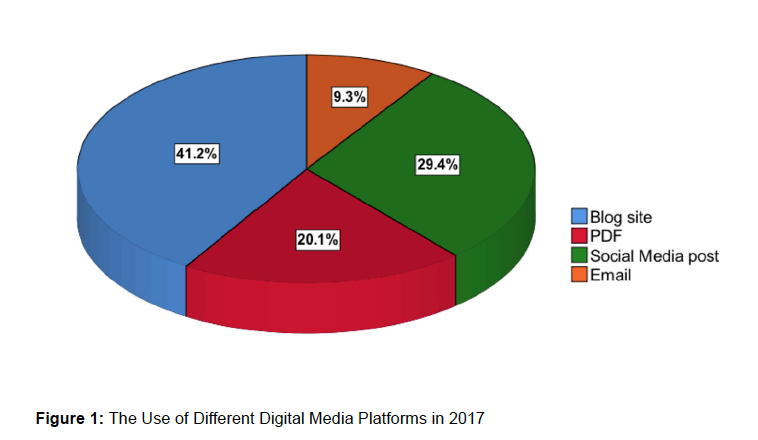

For this study, the researcher analyzed 194 articles published digitally in 2017, and discovered most young Cuban journalists used blog sites as the primary platform for digital content (41.2%). These blog sites were more informal and included a mix of personal narrative, other forms of writings from poetry to short prose, as well as journalism. After blog posts, the second most frequently used digital space for young Cuban journalists was social media platforms, with Facebook group posts being the most frequently used among the sample (29.4%). PDFs that could be disseminated digitally were the third most common format for digital content (20.1%) followed by email at 9.3%

When coding digital content by subject matter, the most common theme for online content were articles about politics (40.2%). These stories ranged from the change in the Castro regime, new policies and laws, international relations and geo-politics to enfranchisement. Stories on culture were the second most posted content online (20.1%) with features, spotlights and highlights on artists, musicians, novelists, filmmakers and the context of their work in a changing Cuba. Stories on economics and social issues equally represented 10.3% of the sampled online content in 2017. Economic stories covered the growing private sector and impacts on travel and commerce to the island stemming from changes in U.S. policy to Cuba, from the Obama to Trump administrations. Stories on social issues examined issues of gender, identity, civil society and public opinion, with some pieces exploring diversity in Cuban society. Lastly, the sample’s remaining two subject areas were education (9.8%) and welfare (9.3%). Content on welfare examined challenges for ordinary Cubans to meet their household needs with current wages and welfare policies. Content on education covered developments and partnerships with Cuban institutions by others in the region, including state policy and changes for education.

In examining framing, the majority of articles were coded as thematic (62%). The largest number of episodic articles were digital content on politics. Roughly 75% of articles on politics were episodic. These stories precisely focused on providing discourse related to a specific statement by a political figure, or policy action in Cuba or towards Cuba. The subject matter with the most thematic approach to framing were stories about welfare. All articles coded under welfare were presented thematically. They were not directly connected to a specific event or news item but examined critical discourse about how changes in Cuba impact both positively and negatively life in Cuba and the lives of Cubans. The topic with the second most episodic framing were articles on economics and social issues. While roughly two-thirds of articles on education and culture were thematic.

Platforms

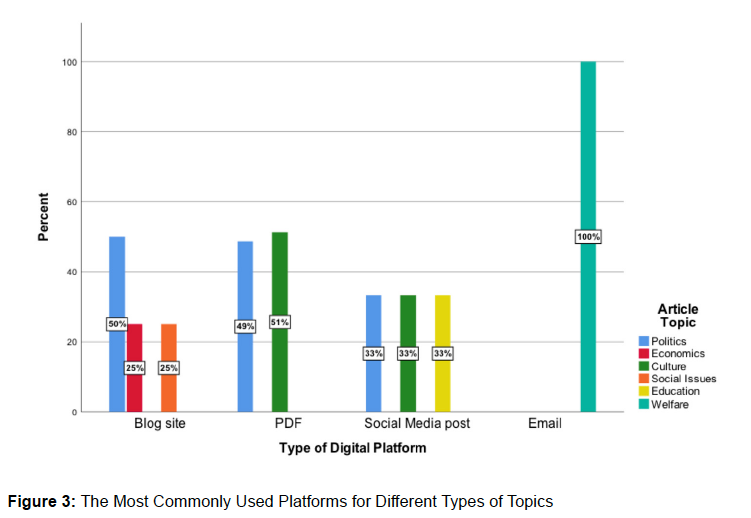

In determining which sites to use, young Cuban journalists were more likely to post stories on politics on a blog site (see Figure 3 below). Additionally, stories on economic issues and social issues were equally posted to blogs. Since these stories carried the most frequent coverage within the sample (reference Figure 2), blogs provided a consistent space to update, tag, and reference previous content on the topic. All of the sampled articles disseminated through emails touched on the topic of the welfare of Cubans. Social media platforms shared content on politics, culture and education. PDF documents published articles on culture, followed by politics.

Discussion and Conclusion

Young Cuban journalists in this study hold their professional virtue of presenting “truths” as a standard for practicing the craft in Cuba. This study showed that self-censorship is an over-simplification of what it means to work in a space of limits to freedom of the press. The act of circumventing institutional constraints is in itself a form of agency within the confines of tolerated discourse by the state. This study questioned how 15 years of prominent Cuban blogs may have influenced new Cuban journalists in the early stages of their careers. The answer is that the technology has been more influential than journalistic positioning. Not one of the journalists sampled in this study positioned themselves as pro-Castro or anti-Castro and the like. The journalists interviewed in this study reinforced their impartiality and distinguished themselves from being activists or partisan. They aimed to practice journalism that they considered presented a Cuban reality that reflects both the good and the bad of Cuban society.

New media platforms primarily appealed to their desire to find alternative spaces to present “truths,” however, in more direct discourse than was possible in their traditional media jobs. It also served as a space for creating a digital community. In instances when digital content became public discourse, embodied in the work of trovadores, artists, and performers, then Cuban journalists are able to address this discourse in traditional media platforms, because such discourse is being tolerated in other forms of expression.

The primary finding here is that the use of old and new media is a two-pronged strategy to search for the ability to practice “real” journalism in spaces that lack full freedoms for the press. Digital platforms serve as spaces for young Cubans with online access for engaging online communities in support of their traditional work. It also allows them to gauge digital feedback for more direct approaches to critical coverage and to consider what approaches can be used to push the boundaries of more traditional reports. The digital sites created for these new journalists are relatively new (under three years), and they have not reached the scale of the more prominent sites, nor are they intended to, because these are sites used by journalists who primarily work for traditional media. However, the aim of this group of journalists is to work within existing traditional media to find ways to reach Cubans at home, with those abroad being a secondary audience, in reverse of the prominent 14 sites.

In comparison to the more prominent Cuban blogs that came before it, this practice is relatively less radical. However, it is an approach worthy of noting for newer entrants to the profession, who primarily aim to work in Cuba, for Cuban media, to serve Cuban audiences. Collectively, both efforts are engaging with media opening, from different corners of the profession. As was the case in Haiti under Duvalierism, it harnesses the potentials of a new medium, for new strategies for providing mediated discourse for society that evaluates the status quo.

The examples of media opening in Haiti and even in Mexico (Hughes, 2008) show that small civic journalism exercises both from mainstream and traditional media, over time, laid the groundwork for future media opening. Of course, Cuba’s context is unique primarily because of its relationship to U.S. policy towards it, even today under President Trump’s administration. Despite the premise that a fully free press remains at odds with the current Cuban state, degrees of freedom of expression can exist, and young Cuban journalists are experimenting in ways to achieve this within the confines of their media system.

NOTES

1 Cubans are able to access digital content offline, ranging in censored foreign and domestic media from films, to television series, and website content at different price points on external hard drives distributed to households by middlemen. The weekly packages can sell for as low as one U.S. dollar.

2 The interviews were conducted in Spanish and English, at the participant’s discretion. Responses in Spanish were translated to English by the primary researcher, who conducted the interviews in Spanish.

References

De Assis, C. (2018, February 28). Cuban online magazine El Estornudo reports it is blocked on the island. Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas. Retrieved from https://knightcenter.utexas.edu/blog/00-19343-cuban-online-magazine-el-estornudoreports-it-blocked-island

Angel Centeno, M. (2004). Society for Latin American studies 2004 plenary lecture: The return of Cuba to Latin America: The end of Cuban Exceptionalism? Bulletin of Latin American Research, 23(4), 403–413.

Firchow, P. (2013). A Cuban spring? The use of the Internet as a tool of democracy promotion by United States Agency for International Development in Cuba. Information Technology for Development, 19(4), 347–356.

García Santamaría, S. (2017). The historical articulation of ‘the People’ in Revolutionary Cuba. Media discourses of unity in times of national debate (1990-2012) (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). The University of Sheffield, Sheffield, U.K.

Henken, T. (2011). A bloggers’ polemic: debating independent Cuban blogger projects in a polarized political context. Cuba in Transition, 21, 171–85.

Henken, T. A., & Porter, M. J. (2016). Translating solidarity: A growing number of Cuban bloggers on the island are finding their way into English translation, and challenging conventional assumptions about solidarity. NACLA Report on the Americas, 48(1), 55–58.

Henken, T. A., & van de Voort, S. (2014). From cyberspace to public space? The emergent blogosphere and Cuban civil society, In P. Brenner, M. R. Jiménez, J. M. Kirk & W. LeoGrande (Eds.), A contemporary Cuba reader: The revolution under Raúl Castro (pp. 196–209). Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Hughes, S. (2006). Newsrooms in conflict: Journalism and the democratization of Mexico. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Iyengar, S. (1996). Framing responsibility for political issues. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 546(1), 59–70.

Kahn, C. (2017, July 2). In Cuba, growing number of bloggers manage to operate in a vulnerable gray space. NPR.org, Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/sections/parallels/2017/07/02/534760028/in-cuba-growing-numbers-of-bloggers-manage-to-operate-ina-vulnerable-gray-area

Kellogg, S. (2016). Digitizing dissent: Cyborg politics and fluid networks in contemporary Cuban activism. Teknokultura, 13(1), 19–53.

Lamrani, S. (2015). Cuba, the media, and the challenge of impartiality. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Lawson, C. (2002). Building the fourth estate: Democratization and the rise of a free press in Mexico. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Loustau, L. R. (2011). Cultures of surveillance in contemporary Cuba: The literary voice of Yoani Sánchez. International Journal of the Humanities, 9(6), 247–253.

Lugo, J. (Ed.). (2008). The media in Latin America. London, UK: McGraw-Hill Education.

Miranda, K. (2016). The good, the bad, and the blog: Reconsidered readings of Cuban blogging. In E. Arapoglou, Y. Kalogeras & J. Nyman (Eds.), Racial and ethnic identities in the media (pp. 95–112). London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Montas-Dominique, M. (2001). The role of the press in helping create the conditions of democracy to develop in Haiti, University of Miami Law Review, 56, 397.

Porto, M. (2012). Media power and democratization in Brazil: TV Globo and the dilemmas of political accountability. London, UK: Routledge.

Roberts, S. (2016). Then and now: Haitian journalism as resistance to US Occupation and US-led reconstruction. Journal of Haitian Studies, 21(2), 241–268.

Rockwell, R., & Janus, N. (2010). Media power in Central America. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Rodriguez, E. D. (2018, January 29). Cuba’s emerging media: Challenges, threats and opportunities. International Journalists Network. Retrieved from https://ijnet.org/en/blog/ cuba’s-emerging-media-challenges-threats-and-opportunities

Timberlake, R. N. (2010). Cyberspace and the defense of the Revolution: Cuban bloggers, civic participation, and state discourse (Unpublished master’s thesis). Loyola University, Chicago, IL.

Venegas, C. (2010). ‘Liberating’ the self: The biopolitics of Cuban blogging. Journal of International Communication, 16(2), 43–54.

Vicari, S. (2014). Blogging politics in Cuba: The framing of political discourse in the Cuban blogosphere. Media, Culture & Society, 36(7), 998–1015.

Vicari, S. (2015). Exploring the Cuban blogosphere: Discourse networks and informal politics. New Media & Society, 17(9), 1492–1512.

Wagner, L. (2017). Nou toujou la! The digital (after-) life of Radio Haïti-Inter. SX Archipelagos, (2). Retrieved from http://smallaxe.net/sxarchipelagos/issue02/nou-toujou-la.html

Dr. Shearon Roberts is an assistant professor of Mass Communication and affiliate faculty in African American and Diaspora Studies at Xavier University of Louisiana. She teaches courses in converged media, social media, multimedia production and Latin America and the Caribbean. She worked as a reporter covering Latin America and the Caribbean and she now studies how journalism practices are evolving in the Caribbean. She has published her research on the role of the media in post-earthquake Haiti. She is currently examining how digital media is transforming both journalism and society in the Caribbean.