Thematic analysis of journalism engagement in practice

By Mark Poepsel

[Citation: Poepsel, M. (2021). Thematic analysis of journalism engagement in practice. #ISOJ Journal, 11(1), 65-87.]

This paper is a qualitative thematic analysis of more than 100 case studies published between 2010 and 2020 in the Gather database of engaged journalism projects. It breaks down these case studies and project blurbs into three organizing themes: content collaborations, facilitating conversation, and random acts of empowerment. Further categorizations are suggested that give us some new language for identifying and strategizing with these crowdsourcing and community outreach practices. One key finding is that nearly a quarter of the cases studied were not about engaging audiences in content creation or interpretation but were about engaging citizens with one another. The community organizer role of the engaged journalism organization is starting to take shape. It will help journalists and scholars alike to have a few shared terms to use when talking about this and other aspects of “what we do when we do engaged journalism.”

Journalism and mass communication scholars talk about two types of engagement. The first primarily involves media economics scholars analyzing how audiences engage with content in ways that garner audience attention. This matters in terms of building theory because it covers new ground in media effects, and it matters to the business of journalism because garnering attention is one of the keys to bringing in revenue. Theory generated in this vein is most useful for those who buy and sell ads and those who study the evolving, increasingly challenging economics of the news industry (Nelson & Webster, 2016).

The second type of engagement carries potentially massive social, cultural, and political impacts and continues to fascinate journalism studies scholars. It falls under the umbrella term “Engaged Journalism,” which, to borrow from Batsell (2015), is journalism which “must actively consider the needs of an audience and wholeheartedly embrace constant interaction with that audience” (p. 145). This branch of theory matters because it gets at the rapidly changing nature of how news is made in digitally networked societies. It also gives scholars the opportunity to develop frameworks for describing and analyzing how the relationships between journalists and participating audience members may continue to evolve.

Arguably, when historians track the major social and political changes of this century they will find that the changing relationships between journalists and audiences played a major role in driving those shifts. The social and cultural implications of engaged journalism are far reaching. For journalists, if the practices known as “engaged journalism” can be more clearly defined, new frameworks might provide direction in chaotic times. For scholars, if we understand engaged journalism better we can continue to build the foundation for explaining how change in news institutions relates to broader social change. This paper identifies and defines engaged journalism practices found in a publicly available case database to contribute a missing link in our research. Specifically, this study separates engagement projects based on content from those based on conversation. Further subcategories are offered and explained. This is followed by a brief discussion about what journalists and scholars might do to use and to build on the simple frames established here.

A Constellation of Approaches

“Engaged journalism” research falls into a group of theoretical approaches aimed at helping us understand how news organizations and citizens might relate successfully in the age of digitally networked communication (Batsell, 2015; Ferrucci, Nelson, & Davis, 2020; Rosenberry & St. John, 2009). It is essential to note that the evolution of digital information and communication technologies is a driver in the push to develop and improve engaged journalism, but engagement happens both in person and online. Many of the practices discussed by journalism studies scholars under the theoretical framework of engaged journalism predate the widespread use of digitally networked communication technologies and can be traced back to the civic/citizen journalism movement (Rosen, 2006; Rosenberry & St. John, 2009). Thus, we should expect engaged journalism practices to utilize digital communication technologies but not always to be rooted in them exclusively.

This study identifies and defines engaged journalism practices as described in a relatively comprehensive database covering projects from 2010-2020. Even in the 2010s many engaged journalism practices started with face-to-face community engagement and incorporated digital communications to augment those practices. Examples of the digital augmentation of face-to-face engagement might include using social media for recruiting and for sharing published content across platforms in an effort to keep conversations and community connections alive after they were first developed at in-person events. Certainly, this study identifies many digital-only or primarily digital engagement projects, but it is important to note how prevalent face-to-face components were. This gives us some context helping connect engagement journalism to its historical precedents, and it indicates some challenges the industry will face in a COVID-ravaged world if we want to continue to foster community engagement in real life.

In the networked age, audiences are also publishers, and publishers do not necessarily need professional news organizations to reach mass audiences. The urgency that drives this study is this: If we can better understand the practices, routines, and opportunities of relatively contemporary engaged journalism projects, we can develop a common vocabulary. This might help us to do a better job of systematically experimenting with engagement beyond what search engine and social media algorithms do to cause us to stay adhered to smartphone content. If the field of journalism is to seriously and strategically approach engagement journalism on a large scale we have to map the terrain first.

In this study, the researcher looked at the Gather database of engagement journalism, which was located at https://gather.fmyi.com/public/sites/20801 when this study was conducted, and which is now located at https://letsgather.in/, as a means of examining almost a decade’s worth of synopses about how engaged journalism was underway.

Covering 2010 to 2020, when the data were analyzed, this collection includes case studies and shorter project briefs. It amounts to a mosaic of snapshots of engagement journalism detailing what tools were used, how journalists, editors and community members contributed, how challenging each project was, and where one might go from here as journalists and researchers. A thematic analysis of 100 case studies and briefs offer some summary terms that might help build engaged journalism theory and to look at the relative prevalence of content-focused projects, that is, those that directly resulted in published news stories, versus those that sought to bring community members physically together to share space and conversation.

Literature Review

Engage with the Literature

Hundreds of academic papers and books cover all sorts of engaged journalism categories. Terms and topics include participatory journalism (Domingo, et al., 2008), solutions journalism (McIntyre, 2019), public journalism (Glasser, 1999; Nip, 2006), civic and citizen journalism (Allan & Thorsen, 2009; Rosenberry & St. John, 2009), and more. What most of the published literature in this area has in common is it deals with the various ways professional journalists and news users relate and collaborate with one another with a strong focus on how news content is shaped and interpreted (Borger, van Hoof, Costera Meijer, & Sanders, 2012; Gillmor, 2003; Lawrence, Radcliffe, & Schmidt, 2018; Rosenberry & St John, 2009; Singer et al., 2011; Wall, 2017). Journalism studies scholars have been most interested in studying engaged journalism from the perspective of professional journalists and editors working in large newsrooms, and early research often focused on newspaper newsrooms (Domingo et al., 2008; Singer et al., 2011). The focus at the start of the 2010s was often of the disruption of existing journalistic routines, organizational structures, and the industry as a whole. While this is a logical starting point and lays the essential groundwork for research into engaged journalism, it does not leave much room for defining and categorizing new routines of practice, particularly those in engaged journalism that are not designed to produce news content. Engaged journalism projects often have engaging a community in civic conversation as the primary goal and informing the audience as a close second. Batsell (2015) notes the rise and fall of the popularity of news organization-hosted events during the civic/ citizen journalism movement, “most from the 1990s and early to mid-2000s” (p. 20). And Batsell (2015) goes on to describe a new financial interest in hosting events as finding new revenue streams for journalism is the primary focus of Batsell’s award-winning book. This paper notes a similar resurgence in live hosted events (post-2010, pre-COVID) and works to place them in context and into categories alongside other engaged journalism programs. To continue to theorize and strategize about engaged journalism, perhaps we need to give as much weight to the term “engaged” as we do to “journalism.” The importance of journalism in a democracy is, generally speaking, readily accepted by professional journalists and journalism studies scholars; whereas, the value of community engagement, aside from the fiscal focus on audience metrics mentioned previously, continues to be debated in journalism circles (Lewis, Holton, & Coddington, 2014; Masip, Ruiz-Caballero, & Suau, 2019; Meyer & Carey, 2014).

Nelson (2019) names the two-headed monster of audience engagement research the “reception- and production-oriented approaches to audience engagement” (p. 7). Reception-oriented approaches are covered by media effects theories and to some extent by market research. Production-oriented approaches are covered by the various categories related to engagement journalism listed above. Where this article aims to push the conversation on engagement forward is in a direction that breaks down content production and event hosting into distinct categories that might be used in practical planning and in further academic analysis. This study seeks to identify, classify, and describe news organization engagement with communities for the sake of community as well as with communities for the sake of content creation.

Participation Spectrum

Previous classifications of participatory journalism, akin to engaged journalism, centered on the level of influence news organizations granted citizens (Nip, 2008, 2009). In their efforts to map the relationships between news organizations and citizens, scholars looked at comments on news websites (Meyer & Carey, 2014), citizen news pages set apart from professional content (Nemanic, 2016), and co-created content among other types of participatory projects (Rosenberry & St. John, 2009). Examinations of citizen journalism, defined as news created by citizens without direct influence from professional journalists (Nip, 2009), suggest that citizens’ ability to publish news online does not necessarily level the playing field between amateurs and professionals (Wall, 2017). These classifications and analyses are useful for discussing different depths of citizen collaboration in news production, but they do not encourage us to examine how deeply news organizations might engage with communities.

Value Proposition

The introduction of reciprocity theory into journalism studies suggests why community engagement is important, that is, how valuable it can be (Borger, van Hoof, & Sanders, 2014; Holton, Coddington, Lewis, & De Zúñiga, 2015; Lewis et al., 2014). People expect reciprocity when they engage with one another. If not immediate recompense, they expect through group dynamics that they might have a favor returned, so to speak, at a later time, and this is true in terms of discursive and agenda setting power just as much as it is with a loaned leaf blower (Borger et al., 2014; Lewis et al., 2014). Reciprocity explains how social capital might be banked and spent, but journalists and news organizations have often sought to remain detached from audiences as “objective” observers of social events rather than active participants. Engaging in reciprocal practices with communities is not a switch that can be turned on. Citing Robinson (2011), Lewis et al. (2014) explain: “Simply put, there are transaction costs associated with engaging audiences, and in many cases journalists cannot (or will not) bear that cost when it cuts into what they see as their core journalistic activities” (p. 11). If journalists and their news organizations are to invest in reciprocity in the name of community engagement, it would help to have some shared understanding of terms and some synthesis of analysis on what appears to be working and what does not.

When social expectations are not fulfilled, trust and other measures of appreciation for the professional field of journalism can falter (Anderson & Revers, 2018). Engaging more will not necessarily mend relationships or alter perceptions, but in an age where dark participation threatens communities and democracy itself (Quandt, 2018; Westlund & Ekström, 2018), it is important to continue to try to understand how news organizations are engaging with their communities. More analysis is warranted even at broad, descriptive levels. For news organizations to engage successfully in meaningful reciprocity in communities, they will likely need to do more than produce audience-influenced content. For news organizations to continue to assert mass influence over meaning making, they may need to foster relationships between community members apart from those meant to generate content. While the civic/citizen journalism movement made efforts in this regard, the movement faltered, too easily dismissed as ideologically motivated and/or too deeply recast as shallow public relations plays (Rosenberry & St John, 2009).

A renewed interest in purposeful efforts to build community cohesion is called for. For news organizations to be platforms for valuable social reciprocity, engagement projects might need to do more than to engage citizens with content. Meaningful engagement may require building and looking after spaces where citizens can engage with each other.

In one of the only major studies to compare digital crowd-sourced journalism practices to “offline forms of audience engagement,” Belair-Gagnon, Nelson, and Lewis (2019) showed that public media journalists tended to prefer face-to-face offline engagement activities. This is an important piece of the puzzle. It suggests that some journalists might welcome a chance to explore new roles as direct organizers of community discussion.

We’re Gonna Need a Bigger Box

This study analyzes cases and (more brief) project descriptions featured in a database geared toward those who are running their own engaged journalism projects or those who are interested in developing them (Gather, n.d.). This paper does not suggest that hosting community forums or crowdsourcing content are new innovations, but what it offers, through a look at nearly a decade’s worth of engaged journalism efforts, is a sort of heat map of engagement complete with the relative prevalence of certain types of projects. It is hoped that by looking for key themes in engaged content creation and in community conversation facilitation we might begin to understand which types of project are most popular and why. This should help us to continue to develop our working vocabulary for engagement journalism and to suggest several areas where further research should be conducted. It may also offer a small contribution to the discussion about how to foster reciprocal journalism in society.

Based on an analysis of 102 projects listed on “Gather, the engaged journalism platform” (Gather, n.d.), carried out between 2010 and 2020, this paper addresses the following research question:

RQ1: What do news organizations actually do when they practice engaged journalism, and how prevalent is the function of fostering community conversation as opposed to the function of fostering collaborative content creation?71

Methodology

The method for this study was thematic analysis. It is most applicable in qualitative research when attempting to make sense of a large text or a large body of texts when the goal is to tease out and explain key themes and the basic concepts that comprise them. The specific method applied here comes from Attride-Stirling (2001), which encourages the unveiling and analysis of thematic networks. Thematic analysis allows for the application of existing theory and for the researcher to notice new themes that may help explain phenomena more completely. In that regard it is a useful method for analyzing efforts which are themselves experimental. Thematic analysis can help solidify knowledge about otherwise short-lived projects and programs.

The process is straightforward. One reads or analyzes a text or group of texts and codes the material. Then, the researcher identifies themes, constructs thematic networks, and describes and explores those networks (Attride-Stirling, 2001, pp. 390–393). Analysis continues until the thematic networks can be summarized and patterns interpreted (p. 394). The hierarchy of analysis starts with basic themes, which comprise organizing themes, which all feed into the global theme. In this case, the global theme is simply “engaged journalism.” The organizing themes and basic themes are mapped in a network displayed and discussed in detail in the findings, all following the example of Attride-Stirling (2001).

The textual basis for this thematic analysis was a body of 102 digital documents. There were 54 case studies of between 1,500 and 3,000 words in length found on the Gather database (Gather, n.d.) along with 48 brief project summaries. These covered a time frame from 2010 to 2020. The news organizations conducting these projects were primarily located in the United States, though a handful originated in Europe. The types of media involved were digital-first news properties, public radio stations, and newspapers’ websites and other digital offerings. About 10%, were grant-funded or non-profit-sponsored projects that, more or less, stand as efforts unto themselves. Other notable project sponsors include the Medium platform itself, college journalism courses, the Huffington Post, ProPublica, and StoryCorps.

Case studies and project summary briefs were collected by the Agora Journalism Center at the University of Oregon often by requesting submissions via word-of-mouth and social media. These do not represent a census of all engaged journalism projects done in the last decade, nor are they a perfectly constructed random sample; however, this collection is the most comprehensive database of journalism engagement projects publicly available. The case studies include details about the goals, costs, challenges, and successes of each case. Case studies and project blurbs also indicate whether or not the primary purpose of each project was to create news content or to bring the community together in other ways.

Where choices had to be made in the classification of projects as primarily conversation-focused vs. content-focused, both the project’s stated purpose and outcomes were taken under consideration. Projects were categorized according to element(s) emphasized the most in the write-ups. For example, if a project included a day-long event put together at great expense featuring dozens or more community members brought together to discuss current issues and it resulted in several news stories it was categorized as “Facilitating Conversation” because this was deemed to be the primary purpose. In other words, cash expenses and time costs were considered in addition to stated goals.

In one sense, the Gather platform is a repository of hope that engaged journalism might work. It’s an attempt to document the history of an evolving journalism practice, which may provide a renewed sense of purpose for the field. For journalism studies scholars to more intricately evaluate and rank types of engagement journalism, some common vocabulary might serve as a collective codebook or guide. Thematic network analysis is the appropriate method for uncovering, explaining, and beginning to analyze the many practices and purposes that comprise what we call “engaged journalism.”

Findings

RQ1: What do news organizations actually do when they practice engaged journalism, and how prevalent is the function of fostering community conversation as opposed to the function of fostering collaborative content creation?

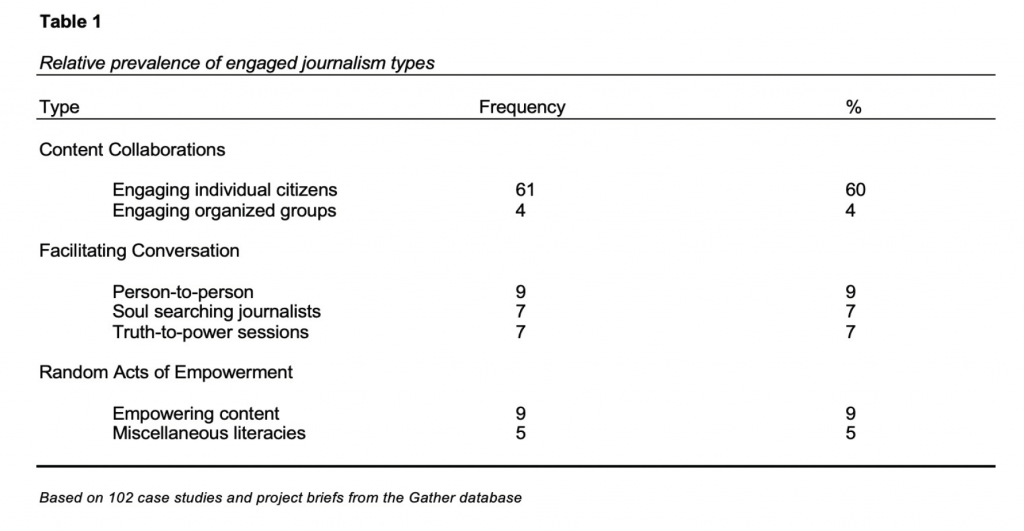

In response to RQ1, content collaborations tended to dominate the cases documented in this engaged journalism database. They made up 64% of the total, compared to 23% geared to facilitating conversation. The 100-plus case study write-ups and project briefs listed in the Gather database are representative of what is possible when news organizations pursue engaged journalism and where we have room to grow as practitioners and researchers. Besides “content collaborations” and “facilitating conversation,” a third organizing theme was identified. It is something of a miscellaneous category referred to here as “random acts of empowerment.”

While many news organizations focus only on engagement as defined as a series of web metrics (Nelson 2019), the project briefs and case studies discussed here focus on community. In some ways these efforts are a continuation of the civic journalism and public journalism movements, which both largely receded in the early 2000s; however, there is promise here for building engines of social reciprocity in communities through journalism. If anyone is going to overcome the “transaction costs” identified by Lewis et al. (2014) and establish community reciprocity through engaged journalism, it would be those who are dedicated and who have the time and often the grant funding to try. But we need to examine what underlies the organizing themes, with special attention paid to “content collaborations” and “facilitating conversation.”

Seven basic themes were identified as branching off of the organizing themes. The basic themes are labeled, and definitions are provided and supported with concrete, empirical examples below. Following the explication of themes are brief discussions of what may be possible in the future. Note that considerations are tempered by the understanding that the COVID pandemic may limit face-to-face engagement efforts by news organizations for at least the near term.

Content Collaborations

Content collaborations comprise 65 of the 102 cases and project briefs studied here, which is 64% of the total. They are defined straightforwardly enough as engaged journalism projects and events where the primary purpose is to gather or contribute to news content. The vast majority of content collaborations are crowdsourced reporting efforts, defined here as the practice of taking large questions or problems and asking a large number of online contributors to help break down and analyze or contribute to the project in small ways. The collective efforts, usually of individual users, are leveraged to compile databases, analyze existing pools of data, and/or to compare experiences. One example of “engaging organized groups” was when an Italian journalist built a database from information contributed by users organized according to municipality. This was a fascinating project and will be detailed below. Engaging organized groups was the smallest category among the basic themes identified in this study.

Crowdsourcing takes many forms, and it can be done online and asynchronously with potentially outsized results, which likely contributes to its popularity. A small number of the “engaging individual citizens” cases mention additional crowd-engaging elements such as crowdfunding or “hackathons.”

One of the most striking notes on the theme of content collaboration is how evenly split the projects were between open calls for collaboration and guided reporting projects. At a glance the Gather platform might appear to focus on projects with specific topics in mind, but 37 of the 65, or 57% of the content collaboration cases, were open-ended calls for content. An example of an open-ended call was the “One River, Many Stories” project based at the University of Minnesota, Duluth, which was noted in a project brief (Featured Projects Archive–Gather, n.d.). The organizing concept was that each story needed to concern the St. Louis River region in northeastern Minnesota. Media formats and story topics varied widely as journalists worked with individual citizen contributors to create a sense of community around this small river basin.

Of the 65 content collaboration cases, in 61 of them, or 94%, journalists engaged directly with individual citizens. This matters because the institutional power differential is greater when news organizations engage with individuals. This may be more popular because it enables journalists to maintain control more easily over story selection, reportage, and framing even as their news organization demonstrates a willingness to engage with citizens in setting the news agenda. Additionally, it is also likely that engaging with groups is the more expensive approach. Coordinating with organized groups to create content requires knowledgeable outreach and often event planning capabilities and budgets. Where organized groups were engaged in content collaboration, there was an even split between open requests for story ideas and guided requests.

A guided request is when a news organization seeks content and insights on a particular topic or story determined by journalists to be newsworthy. A good example of a guided request can be found in the Cittadini Reattivi project. In this case, “about 400 Italian communities have helped [editor Rosy] Battaglia build a detailed map of 15,000 contaminated sites across Italy” as her news organization seeks to report extensively on environmental justice issues (Torchia, 2018, para. 4). When journalists define the topic, this opens up opportunities for contributors to provide information with depth and richness. The tradeoff is that citizens with little knowledge of the subject might only engage as audience members. Arguably the potential to establish reciprocity is present, however, because journalists are taking notice and direct action to address a problem thousands of citizens are having.

The Cittadini Reattivi project is exemplary because by using maps it not only maintains but enhances the detailed information provided by citizens. It is an example of a content collaboration built with posterity and function in mind. The groups in question are municipalities, which are relatively easy to identify and to identify with. The project, as described in the Gather case study was its own standalone site. Battaglia hosted a successful crowdfunding campaign to produce a documentary film (Torchia, 2018). Further follow up is needed to see if this relationship between journalist and communities continues and to see if positive environmental impacts result. This leads to the question of how we might foster ways to make this sort of effort common practice for journalists in organizations of all shapes, sizes, and nationalities.

When individuals are called on to help crowdsource story ideas, news organizations have to manage parallel efforts. These projects often appear to serve a community outreach public relations function and a journalistic one simultaneously, which hearkens back to the civic and citizen journalism projects of the past. Further study is needed to see how these projects may avoid the pitfalls that plagued some of the public journalism projects of the 1990s and early 2000s (Rosenberry & St. John, 2009). This is not to say that journalism is nec75

essarily given short shrift when story ideas are crowdsourced, but when individual citizens are engaged in unguided agenda setting, the resulting news is not necessarily in-depth and issues-focused. What remains to be seen is whether that matters for community building or for leveraging engagement to build journalistic reciprocity. Perhaps the hope for engaging with individual citizens is that for every few human-interest stories gathered through crowdsourced agenda setting there might be a guided crowdsourced project that successfully tackles an issue of national concern. Gather does not offer examples where multiple engagement projects were conducted simultaneously. Though it is not unusual for a digital news standalone site to feature engaged journalism at its core, there are no examples in the database studied here of large-scale news organizations that run mostly or even in large part on engaged journalism projects. Instead, these often appear to be side projects, although they may be recurrent.

By empowering citizens to help set the news agenda, news organizations are responding to the digital age reality that citizens can craft and share news on their own and bypass professionals. Outreach to individuals or groups for the purpose of content collaboration is not foolproof and only rarely leads to the type of journalism Cittadini Reattivi produced. Scholars should examine what might be an appropriate balance between guided and open-ended crowdsourcing.

Sometimes the result of engaging individuals in collaborative content creation can be life-saving. Information such as where to find help after a hurricane or how to try to thrive during the COVID pandemic may become common features of engaged journalism in the future (Featured Projects Archive–Gather, n.d.). One blurb on the updated Gather database site notes:

[With] ‘Rona Call: A Community Info Phone Tree. Free Press’ News Voices team created a guide to help community [members] reach out to five folks [each] and ask them a series of questions about what information they need to stay safe, healthy, and connected. The News Voices also relayed these findings to local journalists to help inform media coverage, raise questions to pose to decision-makers, and suggest how to frame stories in a way that will provide value to communities. (“‘Rona Call: A Community Info Phone Tree’” section)

Tackling issues from the perspective of individual news users may result in a marriage of issues reporting and human-interest framing within a given story (Poepsel & Cox, 2019). Case studies in the Gather database focus more on the goals and challenges of setting up content collaboration projects than they do on content analysis but for anecdotal highlights. Future research should continue to examine the content developed in engaged journalism projects to help us understand the relative prevalence of “hard” and “soft” news. Another key question to ask is whether engaged journalism is incorporated into the core mission of the news organization or if it is more often done in a performative manner.

Facilitating Conversation

The facilitating conversation type of engagement accounts for 23 of the 102 cases, 23% of the projects studied here. This organizing theme is defined as an activity or event hosted by a news organization with the purpose of bringing community members together to discuss issues or to get to know one another rather than to produce news content. There is a difference between meetups convened to generate story ideas or to conduct crowdsourcing efforts and this category. The primary purpose under “facilitating conversation” is community building through fostered discussion as evidenced by details in the texts of these 23 cases and project briefs. News organizations may use these events for multiple purposes such as informing community members about democratic processes and/or promoting the news brand in addition to fostering discussion. Though these types of events do not generate news content, they are not necessarily less essential for the evolving role of a news organization because they may help to maintain or reestablish the organization’s role as facilitator of communicative reciprocity.

A shorter definition: news organizations fulfill the role of conversation facilitator in communities when they strategically plan events to bring community members together to engage in constructive discourse. In a sense, by hosting conversations, most often in-person, news organizations are taking a role once fulfilled in the pages of the newspaper as a marketplace for ideas, applying some structure and guidance, and bringing this activity into physical spaces and digital forums. How does this relate to the civic journalism or public journalism movement of the 1990s and early 2000s? It follows what Nip (2008) observed that some of the of the practices of civic journalism were adaptive and accepted into the DNA, so to speak, of a number of news organizations.

As a national movement, civic journalism may not have shifted the focus of most newsrooms toward what are now called engagement and solutions journalism, but some of the practices live on as news organizations continue to experiment and to assert their role as catalyst for building connective tissue in communities.

Actual practices varied widely. Some curated conversations that appeared in these data were set up as person-to-person meetups. Others brought people in positions of power into conference centers or similar spaces to face questions from citizens in the room. Such events may not raise revenues. In many cases there was not even an attempt to turn these events into money makers, but one consistent aspect of these types of project was that they were designed to improve the standing of the news organization in the community through serving some other social need. For example, an event in Richland, Ohio brought in pregnant women to learn about the available community resources after local reports in RichlandSource indicated high levels of infant mortality in the region (Poole, 2018). Here the engagement portion of engaged journalism happened after the news stories made an impact. The relevant scholarship in this area is solutions journalism research (McIntyre, 2019). Most of the events described in the data that fit this theme were not as focused, however. In fact, it is difficult to classify these events as either “guided” or “open topic” because at times even the guided discussions covered several sweeping municipal issues. Further study will reveal if and how the practices formerly known as civic journalism may be being reconstituted under the engaged journalism umbrella.

After thematic coding and recursive analysis, it was determined that three basic themes comprise the “facilitating conversation” organizing theme. Those basic themes are “person-to-person” meetups, “truth-to-power” sessions, and finally the “soul searching journalists” theme. Each presents unique opportunities for follow-up research.

The person-to-person meetups were the most common, making up nine of the 23 cases, or 9% of the overall cases. These were creative efforts to try to bring community members together to share stories and to attempt mutual understanding. Most were open-ended in nature. Some had the express purpose of bridging divides between ethnic groups or political factions. For example, “After the 2016 election, Colorado Public Radio (CPR) reporters wanted to know how they could help bridge conversation across party lines in an increasingly polarized political climate. So in May, CPR brought together a politically and ethnically diverse group of listeners to share a meal and engage in conversation” (Stevenson, 2018, para. 1). There appear to be local news organizations willing to try to coordinate community connections, even down to the individual level. The individual meetups could be a qualitative case study unto themselves because they exemplify what happens when news organizations attempt a sort of soft-pedaled community organizing. An obvious critique of most of these projects is that they focused on brief events rather than outcomes; however, some resulted in subsequent news coverage, and others provided services not likely to be found anywhere else. For example, one project brought stories from Kentucky inmates to their families via radio (Featured Projects Archive–Gather, n.d.). Many of these communication efforts are costly and experimental and might make more sense as government programs than as community outreach efforts run by online news sites and public radio stations; however, these show there exists a willingness to innovate.

Most of these person-to-person engagement projects were held face-to-face in real life. For some time even after the widespread delivery of a COVID vaccine, members of communities in areas hard-hit by COVID may be reluctant to meet in person. If anything, this is a possible opportunity because the costs of coordinating group discussions are relatively low in virtual settings. Turnout at these events was relatively low, but this was often because they were only designed to be meetups of a few dozen people or so. One possibility is that these become a function of government not simply about government. If the democratic experiment in the United States is to continue, perhaps some previously unthinkable steps need to be taken in the way government, news media, and citizens relate and coordinate with and for one another.

The “soul searching journalists” category refers to seven cases of discussion facilitation where citizens were brought together with news professionals to discuss the industry. The outcome, in this limited sample, was often that members of the public simply wanted to tell journalists what they are doing wrong. Based on the discussions in the Gather database, citizens want better, more inclusive coverage of diverse groups, and they want multiple contexts and points of view provided.

One project brief (“Bridging Divides”) included in this category posed a problem in data analysis because it referenced an entire year’s worth of outreach efforts by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, which may include as many as 500 events that use news as a jumping off point for community education (Featured Projects Archive–Gather, n.d.). Without more in-depth description, it is not clear whether these were each independent outreach efforts or rather similar efforts repeated hundreds of times. Based on the brief, these appear to have been lectures and lessons rather than engagement sessions, so the decision was made to count this in the context of this paper as only one project brief. Further studies could be done on the Pulitzer Center’s work to learn more about the types of engagement practiced. The Center itself is not so much a news organization as it is a facilitator. At any rate, journalists are engaging with communities to discuss media ethics, to explain the role journalists play in the media ecosystem and in society in general, and in limited instances they discussed the public’s news agenda. What ties this category together is the sense in each of these cases and project briefs that leaders in the journalistic field need to hear more from communities that some of them have worked for decades to keep at a detached length.

The final basic theme in this section is “truth to power,” which represents meetings where civic leaders were invited to answer questions from readers and listeners of local news media. A couple of these events were focused on specific issues while the rest were open-ended in nature. While these can serve to maintain the position many news organizations aspire to hold as guardians of accountability, large, open-topic meetings can appear to citizens as invitations for officials merely to pay lip service. Many of the writeups for these events suggest that they ultimately shape and influence news coverage, which is promising. In the age of networked digital communication, tracking outcomes is becoming a necessity. Though most of these cases do not indicate that tracking is happening, future “truth to power” sessions and similar digital platforms set up by news sites could track outcomes. This is another trail for journalists and researchers to follow.

Random Acts of Empowerment

This theme represents a collection cases that have in common some notion of fostering empowerment. Empowering people is an admirable goal, and perhaps it is too harsh to suggest that these are any more random than some of the other events or one-off programs cited above, but what these have in common are that they do not involve citizens and journalists collaborating to craft news content, nor are they meant to bring community members together with one another to address social issues. The primary definition of this organizing theme is an idea that persists in journalism practice that news content itself can be so citizen-focused as to be empowering and to constitute engagement. In the academic literature, content alone does not make for engaged journalism no matter how diverse the intended audience is or how useful the “interactive” database might be. What defines engaged journalism is that there is a two-way (at least) exchange of information and communication of issue agendas. What we see in these examples is usually simply well-meaning, if sometimes patronizing, targeted reporting.

The basic theme of “empowering content” fits this bill. Important to note, this type of reporting can be good journalism. It can be creative, and it may cover a wide range of perspectives, but, for example, sending student photojournalists to document underrepresented communities one day out of the year as an educational exercise might do more to placate guilt about structural inequalities in news coverage than to engage communities in sharing the power of journalism to influence social structures (Bruni, 2018). It is possible that these efforts are the beginning stages of engaged journalism practices. For that reason, they are included in this section and are not labeled “half measures.” Instead, these are indicative of institutional efforts the world over that recreate some inequalities while attempting to tackle others. To travel from “random acts” to the realm of engaged journalism, the circle between journalists and citizens needs to be completed, documented, repeated, normalized, taught, and appreciated with outcomes tracked.

Finally, there is a basic theme called “Miscellaneous literacies.” As it happens, in this database are five community outreach efforts that focused on something other than news. Topics here included poetry, art, computer literacy and good, old-fashioned reading and writing. Encouraging literacies is another way news organizations might build their community brand, but in each of these cases either the news element or the element of community connection was found lacking. One interesting case saw a group of coders come together with news editors to create tools of engagement (Stevenson, 2017). This particular case was too “meta” to be categorized as anything but a literacy engagement. That is, journalists learned something about coding, and engagement tools were made. This explains why this case exists and why it did not fit anywhere else. Efforts at building engagement engines will likely continue and should be encouraged. Perhaps our ability to categorize and analyze will catch up.

Discussion

Most of these engagement projects are not new in nature. Community outreach was part of civic and citizen journalism practice since at least the mid-1980s (Rosenberry & St John, 2009; Ruiz et al., 2011). Community journalism scholars will note that small community news outlets never stopped doing various types of outreach, and when you are part of a faith community, a business community, a family community, an educational community, etc., many things you do under those guises looks quite a bit like the “fostering community” type of engaged journalism. But this is not about news organizations attempting to duplicate community building efforts. Rather it is about the need for shared secular civic spaces and for journalists, or people doing journalism, to build and to occupy those spaces to try to ensure that they function because this is what societies are built on. Forming factions and calling them communities is relatively easy. Making connections between groups to help maintain a functioning society is hard. It is argued here that it is not enough for journalists to assert that through storytelling they create shared community. This does not work in an age of information glut and self-selected news content. Journalists and scholars must be able to demonstrate and solidify in the form of knowledge which news and community development practices actually work to build cross-group mutual understanding to get community-level things done.

How They Made It

This study provides some more terms to define the how of engaged journalism. Perhaps these categories will need to be changed or be refined as we study and practice engaged journalism and solutions journalism more. One main limitation of this study is that it does not break down the various ways individual citizens are engaged. This is good fodder for further study because individual engagement is the core building block and perhaps the best unit of analysis of engaged journalism. As scholars, one can study what motivates individuals to participate in community conversations organized by journalists, and one might also survey community members to better understand what their expectations are for potential outcomes that may result from crowdsourced journalism efforts. McIntyre (2019) noted that “compassion fatigue” can result when people are made aware of problems in the news but see few if any viable solutions (p. 16). One question to pursue is: “What exactly counts as a solution?” Understanding what gets citizens engaged and what they might consider to be socially satisfying outcomes would give clear starting and ending points for practice and research.

It was identified here in the findings, and it matters quite a lot, that individual citizens appear generally to be less powerful and cheaper to contact than organized groups for the purposes of content collaboration. Many in organized and activist efforts would note that they are not as well engaged by news media as need be for them to affect structural change. By engaging more with activists across the political spectrum, journalists might improve society’s understanding of who the various activist groups are and what they want. The cases studied here were in a general sense, safe projects that did not challenge the status quo much, but when journalists attempting to represent the center do not cover left wing action much it makes it that much easier for right wing extremists to label everything to the left of them as a monolith. Engagement projects that treat Black, Indigenous and other People of Color as the “other” and that seek to engage “them” to tell “their stories” indicate a dearth of diversity within news organizations. Engagement can happen in-house too.

Reciprocity as Ultimate Goal

Without studying long-term community effects, it is difficult to say which types of cases did the most to foster journalistic reciprocity, defined again as building a system for shared social capital by fostering community relationships through journalism (Borger et al., 2014; Lewis et al., 2014). Perhaps in future research we may examine which balance of content collaboration and facilitating conversation works best to build social capital. It would make sense to start with successful community outcomes and then backtrack. Observations in this study give us a starting point. Many of the successful content collaboration efforts were guided crowdsourcing projects. Building reciprocity might be conceptually as simple as normalizing the practice of crowdsourcing to prioritize community problems and crowdsourcing to find positive community outcomes. Community engagement platforms such as Hearken, appearing in a dozen of the cases studied here, can be configured to tackle social issues wherein newsrooms use their own reporting as a starting point and use Hearken for more than human interest stories. An appropriate measure of community reciprocity would likely involve surveying community members to see if they trust their local news organization to identify issues and to pursue solutions until meaningful change is achieved. This goes well beyond discussions of solutions as identified in early solutions journalism research (McIntyre, 2019), which is not to say that the research is lacking but that journalism which seeks outcomes is still not the norm.

Conclusions

Thinking of all 102 cases, what seems to be evolving and improving is the level of innovation and sophistication in engaged journalism practice. Many of these projects involved creating databases or coding web applications specifically for the project in question. In many cases, well-regarded investigative journalists had specific stories in mind and went to communities to find people affected by issues, to crowdsource information, and to find social remedies. This method of storytelling should be encouraged as should the tracking of solutions. Open-ended community sessions are important for starting the engagement ball rolling, but journalists prove their mettle by organizing and synthesizing complex information from various sources and stakeholders and by holding the powerful to account until changes are made. Journalists and scholars should not shy away from being the brains of engaged journalism operations. The animus of the crowd gets us mob Twitter, fast-spreading conspiracy theories, and insurrection. When it works, engaged journalism gets results.

It is also noteworthy that the social media platform that comes up most often across these cases is Facebook. As a tool for connecting with community members, it is powerful, but researchers have raised questions about how Facebook functions as a news sharing site (Carlson, 2018). Alternative means of engaging with audiences that are not dependent on third-party platforms may be preferable in the future, particularly in the United States where engagement with news on Facebook may be more polarized and hostile than in other parts of the world (Humprecht, Hellmueller, & Lischka, 2020). News organizations may take encouragement from the examples referenced and alluded to in this study where local communities throughout the Gather database have built their own networked enterprises. This is, after all, what Gather is all about.83

References

Allan, S. & Thorsen, E. (Eds.). (2009). Citizen journalism: Global perspectives, v.1. Peter Lang.

Anderson, C. W., & Revers, M. (2018). From counter-power to counter-pepe: The vagaries of participatory epistemology in a Digital Age. Media and Communication, 6(4), 24–25. http://dx.doi.org/10.17645/mac.v6i4.1492

Attride-Stirling, J. (2001). Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 1(3), 385–405. https://doi. org/10.1177/146879410100100307

Batsell, J. (2015). Engaged journalism: Connecting with digitally empowered news audiences. Columbia University Press.

Belair-Gagnon, V., Nelson, J. L., & Lewis, S. C. (2019). Audience engagement, reciprocity, and the pursuit of community connectedness in public media journalism. Journalism Practice, 13(5), 558–575. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786. 2018.1542975

Borger, M., van Hoof, A., Costera Meijer, I., & Sanders, J. (2012). Constructing participatory journalism as a scholarly object. Digital Journalism, 1(1), 117–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2012.740267

Borger, M., van Hoof, A., & Sanders, J. (2014). Expecting reciprocity: Towards a model of the participants’ perspective on participatory journalism. New Media and Society, 18(5), 708–725. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814545842

Bruni, P. (2018). How the stand uses a community photo walk to build bridges and share untold stories. Retrieved November 20, 2020, from https://gather. fmyi.com/public/sites/20801/search?term=how+the+stand+uses&resultsType=0

Carlson, M. (2018). Facebook in the news. Digital Journalism, 6(1), 4–20. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/21670811.2017.1298044

Domingo, D., Singer, J. B., Vujnovic, M., Paulussen, S., Heinonen, A., & Quandt, T. (2008). Participatory journalism practices in the media and beyond. Journalism Practice, 2(3), 326–342. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512780802281065

Featured Projects Archive–Gather. (n.d.). Retrieved November 19, 2020, from https://letsgather.in/featured-projects/84

Ferrucci, P., Nelson, J. L., & Davis, M. P. (2020). From “public journalism” to “engaged journalism”: Imagined audiences and denigrating discourse. International Journal of Communication, 14, 1586–1604. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/ article/view/11955

Gather. (n.d.). Retrieved February 22, 2020, from https://gather.fmyi.com/public/ sites/20801

Gillmor, D. (2003). Moving toward participatory journalism. Nieman Reports, 57, 79–80. http://ezproxy.lib.utexas.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/ login.aspx?direct=true&db=ufh&AN=10976847&site=ehost-live

Glasser, T. L. (1999). The idea of public journalism. Guilford Press.

Holton, A. E., Coddington, M., Lewis, S. C., & De Zúñiga, H. G. (2015). Reciprocity and the news: The role of personal and social media reciprocity in news creation and consumption. International Journal of Communication, 9(1), 2526–2547. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/3598/1437

Humprecht, E., Hellmueller, L., & Lischka, J. A. (2020). Hostile emotions in news comments: A cross-national analysis of Facebook discussions. Social Media + Society, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120912481

Lawrence, R. G., Radcliffe, D., & Schmidt, T. R. (2018). Practicing engagement: Participatory journalism in the Web 2.0 era. Journalism Practice, 12(10), 1220–1240.

Lewis, S. C., Holton, A. E., & Coddington, M. (2014). Reciprocal journalism: A concept of mutual exchange between journalists and audiences. Journalism Practice, 8(2), 229–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2013.859840

Masip, P., Ruiz-Caballero, C., & Suau, J. (2019). Active audiences and social discussion on the digital public sphere. Review article. El Profesional de La Información (EPI), 28(2). https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2019.mar.04

McIntyre, K. (2019). Solutions journalism: The effects of including solution information in news stories about social problems. Journalism Practice, 13(1), 16–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2017.1409647

Meyer, H. K., & Carey, M. C. (2014). In moderation. Journalism Practice, 8(2), 213–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2013.85983885

Nelson, J. L. (2019). The next media regime: The pursuit of ‘audience engagement’ in journalism. Journalism. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884919862375

Nelson, J. L., & Webster, J. G. (2016). Audience currencies in the age of big data. International Journal on Media Management, 18(1), 9–24. https://doi.org/1 0.1080/14241277.2016.1166430

Nemanic, M. Lou. (2016). Citizen journalism 3.0: Participatory journalism at the Twin Cities Daily Planet. Journal of Applied Journalism & Media Studies, 5(3), 365–382. https://doi.org/10.1386/ajms.5.3.365_1

Nip, J. Y. M. (2008). The last days of civic journalism. Journalism Practice, 2(2), 179–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512780801999352

Nip, J. Y. M. (2009). Routinization of charisma: The institutionalization of public journalism online. In J. Rosenberry & B. St John III (Eds.), Public Journalism 2.0 (pp. 147–160). Routledge.

Poepsel, M., & Cox, J. (2019). Bringing the community to journalism: A comparative analysis of hearken-driven and traditional news at four NPR Stations. Community Journalism, 7, 38–53. http://journal.community-journalism. com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/PoepselCox-CJ2019.pdf

Poole, E. (2018). How Richland Source served local mothers through listening. Retrieved October 11, 2019, from https://gather.fmyi.com/public/sites/20801/sea rch?term=pregnant&resultsType=0

Quandt, T. (2018). Dark participation. Media and Communication, 6(4), 36. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v6i4.1519

Robinson, S. (2011). “Journalism as process”: The organizational implications of participatory online news. Journalism & Communication Monographs, 13(3), 137–210. https://doi.org/10.1177/152263791101300302

Rosen, J. (2006, June 27). The people formerly known as the audience. Pressthink. http://archive.pressthink.org/2006/06/27/ppl_frmr.html

Rosenberry, J., & St. John III, B. (2009). Public journalism 2.0: The promise and reality of a citizen engaged press. Routledge.86

Ruiz, C., Domingo, D., Micó, J. L., Díaz-Noci, J., Meso, K., & Masip, P. (2011). Public sphere 2.0? The democratic qualities of citizen debates in online newspapers. International Journal of Press/Politics, 16(4), 463–487. https://doi. org/10.1177/1940161211415849

Singer, J. B., Domingo, D., Heinonen, A., Hermida, A., Paulussen, S., Quandt, T., Reich, Z., & Vujnovic, M. (2011). Participatory journalism: Guarding open gates at online newspapers. John Wiley & Sons.

Stevenson, R. (2017). How City Bureau recruited volunteer coders to collaboratively build engagement tools. Retrieved November 20, 2020, from https://gather.fmyi.com/public/sites/20801/search?term=how+city+bureau&resultsType=0

Stevenson, R. (2018). How Colorado Public Radio found common ground with the Bread Series. Retrieved October 5, 2019, from https://gather.fmyi.com/public/sites/20801/search?term=2016+election&resultsType=0

Torchia, P. (2018). How Italy’s Cittadini Reattivi Civic Journalism Project is helping local communities. Retrieved September 10, 2019, from https://gather.fmyi. com/public/sites/20801/search?term=2.%09How+Italy%27s+Cittadini+Reattivi+ Civic+Journalism+Project+is+Helping+Local+Communities+&resultsType=0

Wall, M. (2017). Mapping citizen and participatory journalism: In newsrooms, classrooms and beyond. Journalism Practice, 11(2–3), 134–141. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/17512786.2016.1245890

Westlund, O., & Ekström, M. (2018). News and participation through and beyond proprietary platforms in an age of social media. Media and Communication, 6(4), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v6i4.177587

Mark Poepsel is an associate professor of mass communication at SIU-Edwardsville where he has been for eight years. Mark’s research areas include engaged journalism and anti-media sentiment. He teaches media entrepreneurship, science & media literacy, publication design, advanced broadcast writing, and other courses as needed. Mark led a group of journalism students on a study abroad trip to Buenos Aires in 2019. He is fluent in Spanish, conversant in Portuguese. Mark was the president of the SIUE faculty union in 2020-2021. He and Gabriela Renteria-Poepsel are married 18 years with a son, Sammy, and a dog named Tesla.