Did you get the buzz? Are digital native media becoming mainstream?

By Lu Wu

The term “digital native media” describes media companies that were born and grown entirely online. Recently digital native media companies have been repositioning themselvesaway from viral aggregation of second-hand content to generating quality journalism at a level competing with the best old line media. According to media ecology scholars, a nascent media outlet will tend to adopt traditional organizational forms and mimic standard production routines and practices of legacy media, in part to seek legitimacy and stability. This study performed a content analysis of eight years of news content published onBuzzFeed.com. The results showed that while BuzzFeed remains in the early stages of establishing itself as a news organization, it has gradually adopted newsroom routines resulting in more hard news stories that use more official sources.

Introduction

In today’s digital media environment, many traditional news organizations are stuck in recession and struggling to survive continuous revenue drops and newsroom downsizing. The shrinking of newsroom resources has media scholars uneasy as they worry that it may take a toll on the future of journalism (Curran, 2010; Lowrey & Woo, 2010). On the other hand, newer media companies have been thriving in the turmoil and are marching into the new world headstrong. The most recent example isGawker.com, a digital native website known for celebrity and media industry gossip, which recently announced it has enacted a new strategy to focus on political news (Somaiya, 2015).

These companies are referred to in this paper as “digital natives”—that is, they are entirely born and grown online. Digital native media companies differ from traditional news companies in many ways, but one of the most important is that many are expanding in growth and profits. This article argues that digital native companies are thriving not just because Silicon Valley venture capital investors tend to provide them large valuations, but also because these companies have begun to solve problems of how to make profit online. Many digital native media companies started as online content aggregators, curating, branding and distributing viral content such as videos, pictures or posts written by others. These companies benefit from the digital network benefits provided through social media, which they have tapped into not only to generate story content, but as a framework to distribute, consume, share and comment about that content. As Sundar (2008) theorizes, the online consumption of digital media through social websites transforms the media experience by affording the audience the means to engage in a personal way, actively constructing meaning as they consume, share, comment, and create. When executed smartly by digital native media companies, the online environment can further reinforce their dominance over older media companies that have been slow to understand the expanded opportunities outside the printed news.

Despite its rising popularity, digital native media companies were originally viewed as edgy, eccentric, or unseemly by traditional media organizations and media critics (Carr, 2012; Carr, 2014; Miller, 2014). But in recent years, some digital native companies have taken action in repositioning to become something more traditional in format. These moves started with newly hired reporters and editors as they were enticed from legacy media to positions of power at the digital startups.

Media ecology scholars such as Lowrey (2012) have argued that nascent media would adopt organizational forms in order to survive uncertainty in the media environment. Lowery argued that emerging media may have viewed themselves as different from the mainstream, but after all they would change by taking the same forms they rejected at the first place (Lowrey, Parrott, & Meade, 2011). Lowery and others have theorized that newer media companies accrue legitimacy by mimicking many of the standard production routines and practices of legacy media. Once the media entity becomes more established and the existing uncertainty is reduced, however, homogenization and routinization will occur (Lowrey, 2012).

This process has been evident at BuzzFeed as it makes its transformation. Once the brand was best known for producing easily consumed and shared content with a “listicle” format, distinguished by titles such as “7 Easy Dinners to Make This Week.” As of 2014, BuzzFeed was the second-most visited digital native news site, according to a Pew Research Center report from that year. Although it is privately held, the company’s valuation has been estimated at $1.5 billion (Swisher, 2015).

Despite the company’s success and promising future, it’s not yet certain that digital native media such as BuzzFeed will succeed as news organizations. Media watchers have questioned the financial sustainability of a model that depends on fickle trends in social media and constantly evolving technology; other writers have focused in particular on credibility of the online news outlet (Carr, 2014; Jurkowitz, 2014).

This article seeks to start a discussion on the advent of digital native media as serious players in journalism by conducting a case study on BuzzFeed. It argues that BuzzFeed, just like other emerging organizations analyzed by Lowrey et al. (2011), will build a more reputable image and succeed in the news business by modeling its organizational forms after the traditional forms of legacy media organizations.

Shoemaker and Reese (2014) concluded that the consequences of adopting organizational forms can be evaluated through the content. Therefore, this study uses a content analysis of all the news articles published by BuzzFeed since its establishment, focusing on use of sources, news categories, and news topics of those articles: three variables, which are closely related to—perhaps essential for—traditional organizational forms. The analysis presented in this article makes conceptual contributions to the sparse current knowledge about digital native media news practices. It provides systematic information about changes made by BuzzFeedleadership over the years to test the assumption that media companies, in their plan to accrue legitimacy, end up mimicking many of the standard routine practices and forms used by legacy media.

Literature Review

Digital native media

Scholars are intrigued by digital native media because they are unconventional. These are the media companies that succeeded online first, surviving and growing because they had mastered content forms and methods for news dissemination in a world increasingly dominated by the audience’s continuous connection to the Internet, regardless of time, place, or platform (Barthel, Sherer, Gottfried, & Mitchell, 2015). Over time, audiences have learned increasingly to consume their news online, particularly through social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook, which become the main source of sending traffic to the digital native media sites (Friedman, n.d.). Furthermore, digital native media are also leading advertising revenue in the mobile news sector because their mobile ads are more organically designed and individually-targeted to go well with the editorial content and thus feel less jarring to their readers (Moeinifar, 2014).

However, and perhaps because of their reputations made by producing viral content, it is hard for digital native media organizations to change the public perception that they are inevitably associated with shallowness and sensationalism. This can be understandable, considering the reporting that some digital outlets have produced over the years. For example, BuzzFeed is commonly criticized for relying on “listicles”—short, simple and topical articles structured as lists. The listicles are efficient and effective in terms of attracting readers, but the oversimplified format with pictures accompanied by short captions in large size font makes it difficult to take them seriously except for entertainment value. Another digital native media outlet,Gawker.com, has recently announced its transition to a political news site. This may be commended, but it could be difficult, given that it is currently involved in a $100 million civil lawsuit brought by the wrestling professional and TV personality Hulk Hogan after the website published a sex tape featuring Hogan and defended the tape as “real news.” Gawker’s announced move also invites critical comments that it is just another example of a long tradition of applying a tabloid sensibility to politics (Shafer, 2015). The late longtime New York Times media critic David Carr said it well when he brought up the question: is Web journalism a bubble or a business on the make? (2014).

Adopting organizational forms

Before digital native media, scholars were asking similar questions about the uncertain future of blogs. Facing competition from news outlets and each other, bloggers, especially top bloggers with a certain amount of followers and fame, were under constant pressure of updating content frequently to remain financially healthy (Lowrey et al., 2011). This constant challenge of the media environment—what Sparrow called “uncertainty” (2006, p.145)—is what will drive new media organizations to adopt organizational forms for stability and future development (Lowrey, 2012).

Shoemaker and Reese (2014) define an organization as an entity whose members share common goals, are guided by the same rules, and behave within established boundaries. Organizational forms, as operationalized by Lowrey et al. (2011), are expressed by a company as it hires employees, routinizes processes, creates rules and regulations that bind managers and employees, and allocates resources to become specialized. In their study of public issue blogs, Lowrey et al. (2011) found that bloggers would actively seek revenue by writing posts based on popularity and by updating content frequently. They would also adopt editorial policies and rules, and finally, they would adhere to codes of ethics, hire staff, and disseminate information on a regular basis just as a legacy media organization does.

The presumed result of nascent media tendencies to adopt organizational forms is legitimacy (Lowrey, 2012), which is an important ingredient to the developing organizations (Sparrow, 2006). Sparrow argued that the need for legitimacy is necessitated by uncertainty in the media environment. In particular, he linked legitimacy with credibility and attributed the need for legitimacy to the dwindling trust the general public have in the media. According to his view, journalists try to be negative and adversaries towards the government in order to gain trust from the public (2006).

Lowrey (2012) viewed gaining legitimacy as a necessity in order to be competitive and successful. As stated above, organizations gain internal complexity as they implement rules and goals, and they also develop external reputations and form more extensive and complicated relationships with other institutions (Lowery, 2012). Non-traditional media have been observed to seek legitimacy so they can compete with other more established media outlets (Pickard, 2006). Those companies that appear to powerful external institutions and to the public to have a legitimate image tend to develop and thrive (Lowrey, 2012).

Some signs that digital native media have been going through organizational changes are evident. To begin with, newsroom staff sizes at digital native news organizations have expanded in recent years, just as many legacy news organizations have had recent consecutive years of employee downsizing (Jurkowitz, 2014).

New digital native outlets tend to hire more tech-savvy workers, while frequently recruiting reporters and editors from legacy media as well (Jurkowitz, 2014). As they expand, digital news organizations are rapidly increasing their global reach, hiring overseas journalists to represent new regions, gathering stories from locally sourced talent, and leveraging the power of crowdsourcing for content and new story ideas (Friedman, n.d.).

Adopting news routines

Journalists are “persons of their media firms” (Sparrow, 2006, p. 148): they work under the dome of their organizations; therefore they work under the influence of changes happening at the organizational level. One reflection of the influence of organizational level changes is on journalists’ routines (Shoemaker & Reese, 2014).

According to Lowrey, news routines enable “stasis and homogeneity” (2012, p. 219). Media organizations are under constant pressures of operating in limited time, space and resources to produce a news product that can satisfy their audience. Organizations establish routines in order to improve efficiency and to make a profit in most of the cases (Shoemaker & Reese, 2014).

Routines are mostly unwritten rules that provide media workers guidance (Shoemaker & Reese, 2014). Although routines vary among media organizations, Shoemaker and Reese (2014) found that there are similarities within a type of medium (television, print or news networks).

Since the daily routines and roles of legacy news organizations are widely understood and “taken for granted” by audiences, it follows that such practices and processes will increase the legitimacy of adopters for their audiences (Lowrey, 2012, p. 226). Source pattern has also been used as criteria to measure the degree of influence of organizational factors on news routines (Carpenter et al., 2015; Lacy et al., 2013). For newly established organizations, use of sources is an indicator that their reporting is moving beyond rumors and anecdotes and is becoming more conventional.

Journalists rely heavily on routine sources to identify the topics that qualify to be newsworthy (Weaver, 2007). Source selection, as a part of the rules of contemporary journalism, helps journalists make news decisions that are in keeping with journalistic norms (Bennett, 1996). Among several of the findings about source usage that Bennett outlines in his 1996 essay, stories based on official sources were found to dominate journalistic routines. Thus, the reported stories were likely to reflect the reality from the official authorities’ perspective (Bennett, 1996).

Ryfe (2006) argues that journalists rely on official sources for stories as a way to demonstrate the obligation that comes with being a journalist to deliver the “official” version of the story to the public. Another argument is that the over-reliance on official sources is an easy way out for journalists, i.e., they depend heavily on official sources because it’s convenient. Journalists have little time to seek and develop other sources under the pressure of deadlines so they rely on official sources and pre-written press releases (Brown, Bybee, Wearden, & Straughan, 1987). The bottom line is that journalists tend to propagate official versions of reality, unless it is otherwise demanded that they investigate further.

Journalists seem to follow the same journalistic norms or rules unconsciously, although such norms or rules were never documented and distributed among journalists (Ryfe, 2006). But do journalists who work for digital native media also operate under such guidance? If so, it should be reflected in the news content they produce over time.

Hard and soft news

It’s also efficient for news organizations to deal with the demands of heavy workflow by routinizing the process of news making (Tuchman, 1973). Lowrey (2012) observes that newsroom routine is crucial to organizational ecology. The newsgathering routine provides journalists with outlines and expectations regarding methods, resources, and efficiencies. It reinforces the organizational status quo and unifies journalistic practices, but may also serve as a limit to diversity of content and sources (Shoemaker, 2009).

Tuchman (1973) explains that journalists differentiate types of news stories by putting them into major categories, which will decrease the variability of the raw material and facilitate routinization in newsgathering for the organization. Among the categories, classifying stories as hard news or soft news is perhaps the most widely considered analytical strategy (Boczkowski, 2009). Journalists see hard news as reporting that consists of newsworthy facts of events that are potentially open to analysis and interpretation, while soft news items are equal to human-interest stories (Tuchman, 1973). Soft news is generally considered to be entertainment-oriented (Baum, 2002), human interest, or “interesting” stories (Tuchman, 1973, p. 176).

However, Boczkowski and other scholars have addressed the trend of “softening of news” in contemporary journalism (Baum, 2002; Boczkowski & Peer, 2011; Schudson, 2003). Contrary to the traditional sense that news focusing on political and cultural values is categorized as hard news, Boczkowski (2014) writes that political news stories more and more often are being presented in a soft news format (feature, opinion, commentary, and alternative views). Hamilton (2004) explained that soft-approach news stories are cheaper to produce and are more popular among readers compared to the fact-based public affairs approaches.

Research Questions and Hypotheses

Guided by these concepts of organizational forms, news routines, source usage, and news categories, this study analyzes the organizational level and routine level changes made by native digital sites by examining the content produced by BuzzFeed news before and after it shifted from an entertainment-oriented online content aggregator to an original news content generator.

BuzzFeed was the second-most visited digital native news site in 2014 (Pew, 2015). CEO Jonah Peretti, speaking of his goal to expand the organization’s journalistic horizons, said “BuzzFeed News has the potential to become the leading news source for a generation of readers who will never subscribe to a print newspaper or watch cable news show” (Honan, 2014, para. 23).

This study focuses on BuzzFeed as a subject for two reasons: First, BuzzFeed is a good example of the transition from content aggregator to news content creator. The website hired highly regarded Politico editor Ben Smith in 2012 to launch a serious transition into the news business, and by 2014, the company’s reporting work had gained the recognition of many traditional news media for its quality and investigative depth; and second, BuzzFeed has its own archive that hosts all of its past content.

This study hypothesizes that the following organizational level and routine level changes took place under the current leadership:

H1: The content published after 2012 will have a greater number of sources per story than content published before 2012.

H2: The content published after 2012 will have a greater number of official sources than content published before 2012.

Given the fact that digital native news sites are actively involved in political reporting, this study also seeks to examine the proportion of soft and hard political news and to test if the “softening of news” (Boczkowski, 2009) trend has also impacted BuzzFeed. Therefore, this study asks:

RQ1: What are the most common news topics BuzzFeed reported on before and after 2012?

RQ2: What are the distributions of hard news and soft news stories before and after 2012?

RQ3: Are more political news stories being told in soft news format after 2012 than before 2012?

Method

This study is a content analysis of news articles published by BuzzFeed. As stated earlier, the hiring of trained journalists is a move BuzzFeed made to show its commitment to improve journalism practice; however, a systematic analysis is needed to examine at the craft level how the practice is actually reflecting the professionalism at BuzzFeed.

Because content itself is shaped by other antecedent conditions including organizational characteristics, news routines, and practices (Berkowitz, 1997; Lacy, 1987; Riffe, Lacy & Fico, 2014; Shoemaker & Reese, 2014), it follows that changes atBuzzFeed’s organizational level have influenced its journalistic product. Conducting a content analysis of BuzzFeed’s publications using empirical observation and measurement provides the opportunity through inference to understand how that content was affected by forces at the organizational level.

Sampling

The population for the study consists of all news articles (published under theBuzzFeed News banner) from January 1, 2007 to October 31, 2015. BuzzFeed provides an archive of past content at http://www.buzzfeed.com/archive. The archive starts on November 1, 2006, and continues to the most current date.

Although there is limited guidance on representative sampling approaches for online media, especially digital native media sites, this study used the constructed weeks sampling method suggested by studies on the online segment of traditional media (Hester & Dougall, 2007; Wang & Riffe, 2006). Two constructed weeks of each year were used to conduct the content analysis with two sets of randomly selected weekdays to construct the composite. Use of the constructed week is preferable to both simple random sampling and using consecutive days in order to avoid oversampling and ignoring between-week differences (Riffe et al., 1993). Using two constructed weeks has been shown to be efficient and effective to represent accurately one year of content of online news sites (Hester & Dougall, 2007; Wang & Riffe, 2006). Although the archive provides two months of content in 2006, the year is excluded from the sample because of it was not possible to construct a representative two-week sample.

The final sample consists of a total of 912 articles.

Coding

The unit of analysis was each article. Four predictor variables were used in analyzing the articles: news categories (hard news or soft news), number of sources, source type, and news topic.

News Categories: Hard news is defined as news that’s written in inverted pyramid format and commonly focuses on immediate news value and broad social interest. Soft news is defined as stories written in feature style, commentary or other unconventional formats such as a list of pictures with descriptive captions.

Sources: Due to low coder reliability, reported categories for source type were reduced to three (official source, unofficial source, and social media source) from an initial set of seven (government official, police force, press release/spokesperson, experts, legal representatives, individuals and social media source). Official sources were defined as those who speak for individuals or organizations, including: government officials, company or organizational spokespersons, and official government reports. Unofficial sources include individuals who speak on their own about their own opinions. This group includes victims, relatives of victims, university professors, and individual business persons. Social media sources are screenshots of Tweets, Facebook posts, etc.

New topics: News topics were coded into 12 categories that were adapted from categories used by Stempel (1985): politics, war and related crisis, economy/business, education, entertainment, crime, accidents/disasters, technology, human-interest, sports, science, health and environment, arts, lifestyle, animal and miscellaneous.

To ensure reliability, 10% (n = 87) of the selected dates were randomly chosen for double-coding by the researcher and a second coder. In the process of training the independent coder, the researcher refined the list of rules for the coding process. In particular, the categories of sources were reduced and disagreements concerning news categories were discussed and resolved. Krippendorff’s alpha was used to calculate the agreement between the researcher and the independent coder in order to limit the possibility of reaching agreement by chance (Krippendorff, 2004). Reliability on hard or soft news was .89, agreement on types of sources was .85 and agreement on news topics was .87. The frequency count of the number of sources used in each article correlated at .95 (Pearson’s r) between the coders. Pearson’s r is often used to measure the reliability on interval- and ratio-level data (Riffe et al., 2014, p.118).

Results

Among the total articles, 11.4% (n = 104) were published in the five years before 2012 and 88.6% (n = 808) were published in the four years after January 1, 2012.

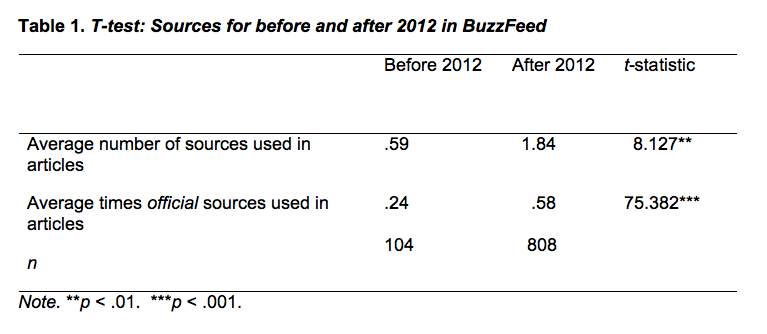

The first hypothesis concerns the mean number of sources in news stories. Before 2012, the average number of sources in a news story was .59. After 2012, the average number of sources in a news story was 1.84. An independent-sample t-test confirmed significant differences between the two groups (see Table 1). Therefore, H1 of increased story sourcing was supported (p < .01).

The second hypothesis suggests that in content published after 2012, official sources will be quoted more often than in content published before 2012. Before 2012, the average number times official sources were quoted was .24; after 2012, it was .58. There was a significant difference between the two means with p < .001. H2 was also supported.

The three research questions require a comparison of news topics and formats of articles published before and after 2012. Due to extremely small numbers of stories in some categories, the reports were collapsed from science, health and environment categories into science; and arts, lifestyle, animal and miscellaneous categories were merged into lifestyle.

The three research questions require a comparison of news topics and formats of articles published before and after 2012. Due to extremely small numbers of stories in some categories, the reports were collapsed from science, health and environment categories into science; and arts, lifestyle, animal and miscellaneous categories were merged into lifestyle.

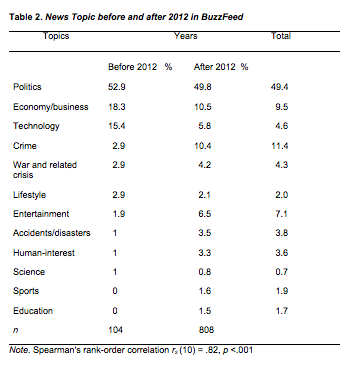

RQ1 sought to enumerate the news topics BuzzFeed reported on before and after 2012. As Table 2 shows, nearly half the news articles BuzzFeed reported about were political news. The next-most reported topics were economy/business, tech and crime. A Spearman’s rank-order correlation illustrated similarity of topic agendas before and after 2012. There was a strong, positive correlation between the two periods, which was statistically significant (rs (10) = .82, p < .001). Whatever else may have changed in 2012, BuzzFeed’s “topic mix” (Riffe et al., 1986; Stempel, 1986) remained the same.

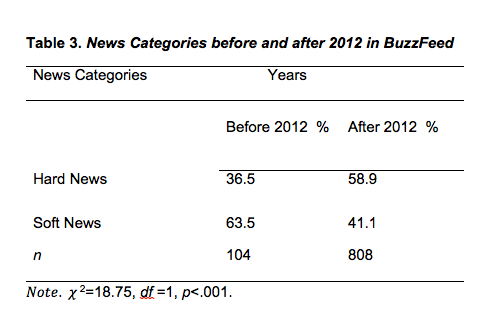

RQ2 asks the percentage of hard news and soft news before and after 2012. As shown in Table 3, more than 60% of stories were soft news before 2012 but the percentage dropped to 41% after 2012. A chi-square test confirmed a significant difference in the distribution of hard news and soft news before and after 2012 ( 2(1) = 18.75, p < .001).

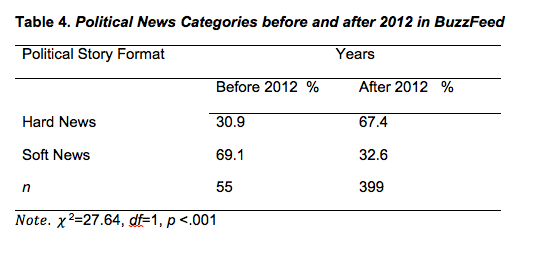

RQ3 specifically inquires about the news categories of political news stories before and after 2012. A chi-square (see Table 4) test indicated that significantly more political news stories were told in the hard news format after 2012 than before ( 2(1) = 27.64, p < .001).

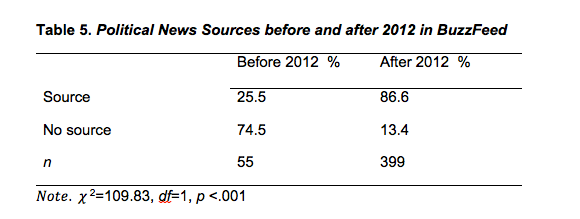

Another chi-square test showed that when reporting on political news, articles published after 2012 were significantly more likely to use sources than articles published before 2012 (see Table 5). But there was no significant difference in source use between political news and other news topics (2(1) = .53, p = .47) in general.

Discussion

This study shows that BuzzFeed, though it is in the early stages of establishing status as a news organization, has made significant changes in progressing to its goals.

Shoemaker and Reese’s Hierarchy of Influences Model (2014) suggests that organizational forms and news routines will influence media content. This study reveals that under new editorial leadership, BuzzFeed has gradually adopted routines resulting in more hard news stories, thus beginning to appear like other more “mature” news organizations. Furthermore, just as traditional news media reports rely heavily on official sources for story information (Carpenter, 2008; Lemert 1989), so too does BuzzFeed.

Although the findings suggest news coverage by BuzzFeed is featuring more sources, more hard news, the topic emphasis stays the same. The study found that there was a strong strength of association in news topics between the period before 2012 and after 2012. Politics and economics/business were the top two most covered news topics in both periods. This indicates that BuzzFeed maintains a focus on these issues in news reporting despite the shifts inside the organization. It honors its audience. The website has adopted routines and forms that promote efficiency and legitimacy, without changing “character.” Audiences can come back to BuzzFeed and find topics they have always consumed but now the stories are better reported.

The observed change of patterns is also consistent with the anticipated pattern of the organization’s increasing newsroom resources: more beat reporters were hired to cover news in culture, and society; and more international bureaus were opened to provide on-the-ground news feeds. However, these changes may also be explained byBuzzFeed’s change of categorization of its content. Before 2012, stories categorized as “news” and listed under the BuzzFeed News banner were almost solely about politics or politicians, while other stories with news value were put under another section of the website. After 2012, the selection of news became more inclusive; therefore, in the coding process we saw an increasing number of different subjects being categorized as “news” over the years. However, some stories that were definitely reported in hard news format were still placed under other banners (BuzzFeed LGBT, BuzzFeed Celeb, etc.)

Ironically, BuzzFeed News has demonstrated the opposite of the trend toward a “softening of news” as identified in media organizations (Boczkowski, 2012). Before 2012, BuzzFeed published twice the number of soft news stories as hard news. This number then reversed after 2012. Also, stories that were told in hard news format were more likely to include quotes from sources than stories told in the soft news format.

The dramatic increase of hard news stories reflected the institutional level changes in the reporting goals of BuzzFeed. In previous scholars’ work, the “softening of news” has been attributed to growing competition with the rise of 24-hour cable news, along with the high cost of producing issue-based public affairs stories, which tended to be less appealing to audience and therefore less financially rewarding than personality-based opinion, commentary, and non-public affairs stories (Hamilton, 2004). The trend toward “softening of news” thus has been interpreted as driven mainly by financial incentives. But to BuzzFeed, financial constraints seem to be less a concern than to other media organizations. BuzzFeed reported a net profit of $2.7 million for the first half of 2014, and had recently received a $200 million investment from NBCUniversal (Ha, 2015). Despite the fact that hard news is expensive to produce, BuzzFeed with its brand and digital model, can apparently afford to do it and is taking its reporting to a professional level.

This study also found that BuzzFeed focuses on political reporting. Scholars who studied contributions to the political sphere by alternative media noted that they often provide information on issues that were neglected by mainstream media, and they offer diverse voices, alternative perspectives, and mobilizing information (Rauch, 2015). Listicle articles such as “7 Things Democrats Would Have Freaked Out About If Bush Had Done Them” was seen by some people as BuzzFeed’s contribution to individuals’ knowledge of public and political affairs while capitalizing on the “soft” nature of the original listicle form (Maynor, 2014).

But BuzzFeed seems to have moved beyond just providing peripheral information about politics to people who are accidentally drawn to it because of entertainment elements; as an organization it appears to have become more serious and committed. Political news accounts for about half of all the news BuzzFeed reports both before and after the leadership change in 2012. But political news reported after 2012 was more likely to be in hard news format and contain more sources than those from before 2012. More recently, BuzzFeed has left the “kids table” and joined mainstream media to land interview opportunities with top political figures. For example, in a mixture of viral marketing and political news, President Obama sat down with BuzzFeed for a 10-minute interview in early 2015. The resulting video, titled “BuzzFeed Presents: Things Everybody Does But Doesn’t Talk About,” featured Obama mugging in front of a mirror in the Oval Office as he practiced a message about a significant deadline for the new healthcare law. The final video features the president of the United States taking selfies, making funny faces in a mirror, and mouthing his lines, all directed at the message “the deadline for signing up for health insurance is February 15th.” Needless to say, the video was “shareworthy”—it got over 22 million views on YouTube within the first 24 hours, and must have been considered a success by editors and White House public relations coordinators. A New York Times story opined that the interview showsBuzzFeed News has emerged as a serious news organization as it partnered with the most official of sources—the White House—to put out a public affairs message while connecting with millennials (Ember, 2015). Importantly, it also showed BuzzFeed’s ability to apply the organizational brand underneath a normally dry political message—it is hard to imagine a similar video could have been produced by a legacy media company such as the The Wall Street Journal or The New York Times, for example.

One other finding of this study is BuzzFeed’s frequent use of social media as sources. Nearly one in 10 articles contained some form of social media sources. These were usually in a form presenting screenshots of people’s tweets, Facebook posts, or Instagram posts about a topic without further editorial development. Scholars have discussed the use of social media sources in risks and crisis, particularly when journalists are working in emergency situations and are desperate to gather valuable information and report on as many aspects of the crisis as possible (Fontenot, Luther, & Coman, 2014; Westerman, Spence, & Van Der Heide, 2014). Although digital native news sites are not the only outlets to use social media sources (other cases are seen inThe New York Times as well, for example) it still raised concerns ranging from the credibility of sources, to the quality of journalism by non-professionals, to ethical questions about permission of use or privacy.

Limitations and Conclusions

This study found significant differences in news coverage by BuzzFeed both pre- and post-leadership change in 2012. The findings correspond with what institutionalism theory has suggested regarding organizational level analysis. However, it takes more than a single study to determine whether the adoption of organizational forms is intentional. This also reflects the inherent limitations of content analysis: the connections between results and interpretation are speculative and implied by a correlation suggested in the literature. Future studies could conduct a survey of digital native media employees and managers to provide more direct evidence about how decisions were made in implementing changes and how adopting organizational forms impacts daily routines, financial motivations, and resource allocation.

This study is also limited by the fact the results may not be generalized to the entire population of digital native media. Digital native media companies are in different stages of their development—some of them are worth billions of dollars and expanding, while others remain small, nonprofit, and local (Jurkowitz, 2014). Their content and format specialization differs as well. For example, the Marshall Project is a nonprofit online journalism organization focusing on issues related to criminal justice. This case study is skewed toward digital native media companies with diverse content and formats, with more established distribution and branding, and whose changes are visible to the public eye because of their popularity.

Another limitation is that the sample for this study relied solely on BuzzFeed’s own archive. As Lacy et al., (2015) noted, using databases or archives as a sampling tool can challenge the comprehensiveness and comparability of the sample collected. To be specific, in this study, it’s unclear how much of the content that was published in the early days was archived and whether the archived content was selected for any particular reasons or according to any specific news values.

However, despite these limitations, this study provides a unique look at the organizational norms and rules adopted by digital news media. It’s promising that may will keep growing into a much bigger force in the news business, especially online news that is targeting younger users. It is important to continue learning more about these news organizations and how they can influence the traditional legacy news industry in the future.

References

Barthel, M., Sherer, E., Gottfried, J., & Mitchell, A., (2015, July 14). News habits on Facebook and Twitter. Pew Research Center Journalism and Media. Retrieved fromhttp://www.journalism.org/2015/07/14/news-habits-on-facebook-and-twitter/

Baum, M. (2002). Sex, lies, and war: How soft news brings foreign policy to the inattentive public. The American Political Science Review, 96, 91-109.

Bennett, W. L. (1996). An introduction to journalism norms and representations of politics. Political Communication, 13(4), 373-384.

Berkowitz, D. A. (1997). Social meanings of news: A text-reader. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Boczkowski, P. J. (2009). Rethinking hard and soft news production: From common ground to divergent paths. Journal of Communication, 59(1), 98-116. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2008.01406.x

Boczkowski, P. J. & Peer, L. (2011). The choice gap: The divergent online news preferences of journalists and consumers. Journal of Communication, 61(5): 857-876. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01582.x

Brown, J. D., Bybee, C. R., Wearden, S. T., & Straughan, D. M. (1987). Invisible power: Newspaper news sources and the limits of diversity. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 64(1), 45-54. doi:10.1177/107769908706400106

Carpenter, S. (2008). How online citizen journalism publications and online newspapers utilize the objectivity standard and rely on external sources. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 85(3), 531-548.

Carpenter, S., Nah, S., & Chung, D. (2015). A study of U.S. online community journalists and their organizational characteristics and story generation routines. Journalism, 16(4), 505-520.

Carr, D., (2012, February 5). Significant and silly at BuzzFeed. The New York Times.Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/06/business/media/at-buzzfeed-the-significant-and-the-silly.html

Carr, D., (2014, January 29). As I was saying about Web journalism … a bubble, or a lasting business? The New York Times. Retrieved fromhttp://www.nytimes.com/2014/01/30/business/media/as-i-was-saying-about-web-journalism-a-bubble-or-a-lasting-business.html

Curran, J. (2010). Future of Journalism. Journalism Studies,1, 1-13.

Ember, S. (2015, February 8). Vox and BuzzFeed obtain interviews with Obama. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/09/business/media/vox-and-buzzfeed-obtain-interviews-with-obama.html?_r=0

Friedman, A. (n.d.). Going viral. Columbia Journalism Review. Retrieved fromhttp://www.cjr.org/feature/going_viral.php

Fontenot, M., Luther, C. A., & Coman, l. (2014). Coverage of Japan’s tsunami included few social media sources. Newspaper Research Journal, 35(4), 141-153.

Ha, A., (2015, August 18). BuzzFeed confirms $200M investment from NBCUniversal.Tech Crunch. Received from http://techcrunch.com/2015/08/18/buzzfeed-nbcuniversal/

Hamilton, J. (2004). All the news that’s fit to sell: How the market transforms information into news. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Hester, J. B., & Dougall, E. (2007). The efficiency of constructed week sampling for content analysis of online news. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 84(4), 811-824.

Honan, M. (2014, December17). Inside the Buzz-Fueled media startups battling for your attention. Wired. Retrieved from http://www.wired.com/2014/12/new-media-2/

Jurkowitz, M. (2014, March 25). The growth in digital reporting. Pew Research Center Journalism and Media. Retrieved from http://www.journalism.org/2014/03/26/the-growth-in-digital-reporting/

Jurkowitz, M. (2014, March 26). Is there a business model to sustain digital native news?Pew Research Center Journalism and Media. Retrieved fromhttp://www.journalism.org/2014/03/26/is-there-a-business-model-to-sustain-digital-native-news/

Krippendorff, K. (2004). Reliability in content analysis. Human Communication Research, 30(3), 411-433.

Lacy, S. (1987). The effect of intracity competition on daily newspaper content.Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 64(2), 281.

Lacy, S., Wildman, S. S., Fico, F., Bergan, D., Baldwin, T., & Zube, P. (2013). How radio news uses sources to cover local government news and factors affecting source use.Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 90(3), 457-477.

Lacy, S., Watson, B. R., Riffe, D., & Lovejoy J. (2013). Issues and best practices in content analysis. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 92(4), 791-811.

Lemert, J. B. (1989). Criticizing the media: Empirical approaches. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Lowrey, W., & Woo, C. W. (2010). The news organization in uncertain times: Business or institution? Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly,87(1), 41-63.

Lowrey, W., Parrott, S., & Meade, T. (2011). When blogs become organizations.Journalism, 12(3), 243-259.

Lowrey, W. (2012). Journalism innovation and the ecology of news production institutional tendencies. Journalism & Communication Monographs, 14(4), 214-287.

Maynor, J. (2014, Summer). The bastard child of the cat listicle and the concern troll: New media, democratic practices and domination. Paper presented at the meeting of American Political Science Association, Washington, DC.

Millennials and political news, (2015, May 28). Trust levels of news sources by generation. Pew Research Center Journalism and Media. Retrieved fromhttp://www.journalism.org/2015/06/01/millennials-political-news/pj_15-06-01_millennialmedia13/

Miller, C. (2014, August 12). Why BuzzFeed is trying to shift its strategy. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/13/upshot/why-buzzfeed-is-trying-to-shift-its-strategy.html

Moeinifar, J. (2015, November 24). How digital publishers are cashing in on increased mobile ad spend. Viafoura. Retrieved from http://viafoura.com/blog/digital-publishers-mobile-ad-spend/?__vfz=tc=84Z4hX9dOua

Pew Research Center (2015). Digital: Top 50 Digital Native News Sites (2015). Retrieved from http://www.journalism.org/media-indicators/digital-top-50-digital-native-news-sites-2015/

Rauch, J. (2015). Exploring the alternative-mainstream dialectic: What “alternative media” means to a hybrid audience. Communication, Culture & Critique, 8(1), 124-143.

Riffe, D., Ellis, B., Rogers, M. K., Van Ommeren, R. L., & Woodman, K. A. (1986). Gatekeeping and the network news mix. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 63(2), 315-321.

Riffe, D., Aust, C. F., & Lacy, S. R. (1993). The effectiveness of random, consecutive day and constructed week sampling in newspaper content analysis. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 70(1), 133-139.

Riffe, D., Lacy, S., & Fico, F. (2014). Analyzing media messages: Using quantitative content analysis in research. New York, NY: Routledge.

Ryfe, M. D. (2006). The nature of news rules. Political Communication, 23(2), 203-214.

Schudson, M. (2003). The sociology of news. New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

Shafer, J. (2015, November, 20). Welcome to the freak show, Gawker. You’ll fit right in.Politico. Retrieved from http://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2015/11/gawker-politics-213379 – ixzz3tGabjRPl

Shoemaker, P. J. (2009). Gatekeeping theory. New York, NY: Routledge.

Shoemaker, P. J., & Reese, S. D. (2011). Mediating the message. New York, NY: Routledge.

Somaiya, R. (2014, February 9). Bill Keller, former editor of the Times, is leaving for news nonprofit. The New York Times. Retrieved September 17, 2015 fromhttp://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/10/business/media/bill-keller-former-editor-of-the-times-is-leaving-for-news-nonprofit.html?_r=0

Somaiya, R. (2015, November 17). Gawker to retool as politics site. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/18/business/media/gawker-politics-media.html?_r=0

Sparrow, B. H. (2006). A research agenda for an institutional media. Political Communication, 23(2), 145-157.

Stempel, G. H. (1985). Gatekeeping: The mix of topics and the selection of stories.Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 62(4), 791.

Sundar, S. S. (2008). The MAIN model: A heuristic approach to understanding technology effects on credibility. In M.J. Metzger & A. J. Flanagin (Eds.), Digital media, youth, and credibility (pp. 72-100). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, dol: 10.1162/dmal.9780262562324

Swisher, K. (2015, July 30). NBCUniversal poised to make big investments in Buzzfeed and Vox media. Recode. Retrieved from http://recode.net/2015/07/30/nbcuniversal-poised-to-make-big-investments-in-buzzfeed-and-vox-media/

Tuchman, G. (1973). Making news by doing work: Routinizing the unexpected. American Journal of Sociology, 79(1), 110-131. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2776714

Tuchman, G. (1978). Making news: A study in the construction of reality. New York, NY: Free Press.

Wang, X. & Riffe, D. (2006). An exploration of samples sizes for content analysis of theNew York Times web site. Web Journal of Mass Communication Research, 20. Retrieved from http://dspace.nelson.usf.edu/xmlui/handle/10806/2879

Weaver, D. H. (2007). The American journalist in the 21st century: U.S. news people at the dawn of a new millennium. Mahwah, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates.

Westerman, D., Spence, P. R., & Van Der Heide, B. (2014). Social media as information source: Recency of updates and credibility of information. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 19(2), 171-183. doi:10.1111/jcc4.12041

Lu Wu is a doctoral student and Roy H. Park Fellow in the School of Media and Journalism at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. She earned a Master of Science degree in journalism from Ohio University. Her research focuses on organizational behavior of digital media. She has also conducted research on the topics of media representation of post-traumatic stress disorder in veterans and the framing effects of reporting about electronic cigarettes.