Cued up: How audience demographics influence reliance on news cues, confirmation bias and confidence in identifying misinformation

By Amber Hinsley

[Citation: Hinsley, A. (2021). Cued up: How audience demographics influence reliance on news cues, confirmation bias and confidence in identifying misinformation. #ISOJ Journal, 11(1), 89-109.]

The influence of political ideology on audience perceptions of news reports and misinformation is well established, along with its role in selective exposure and confirmation bias. The impact of other identity demographics, like education, age, gender and race, have drawn less attention regarding how the public assesses potential misinformation. This study explores the influence of demographics on the public’s reliance on news cues such as headlines and photos and also examines the impact of demographics on confirmation bias as well as confidence in identifying fake news.

A recent Pew Research Center report might have understated national sentiment when it concluded that “Americans continue to have a complicated relationship with the news media” (Gottfried, Walker & Mitchell, 2020, para. 1). In that report, Pew noted the deep partisan divide in perceptions of news coverage: Republican and Republican-leaning adults were more likely to expect articles to be inaccurate and for journalists to intentionally mislead their audiences. It is perhaps not surprising, then, that other studies have established the role of political ideology in individuals’ perceptions of fake news and misinformation, including selectively choosing facts (Schaffner & Roche, 2017) and ignoring cues like misleading headlines because the material reinforces their political opinions (Moravec, Minas & Dennis, 2019). The influence of other demographics—such as education, age, gender and race—have received less attention in studies of how the public assesses potential misinformation, and how journalists can use that knowledge to better engage with news consumers and work to overcome material that exploits oppositional narratives.

Through a national U.S. survey, this study uses social identity theory to examine a range of demographic variables in the context of the public’s reliance on news cues such as headlines, links in stories, and personal research to determine if factors in addition to ideology have an influence on individuals’ assessments of potential misinformation. The present research also explores the impact of demographics on confirmation bias as well as confidence in identifying fake news. Social identity theory helps explain the connection individuals feel toward their social groups—including ones that define their sense of belonging via race, gender and political ideology (Go, Jung & Wu, 2014)—and why those connections can influence assessments of misinformation. The results of this project reinforce the significant influence of political ideology on news consumers’ reliance on particular news cues when evaluating potential misinformation. Political ideology also was a predictor of the inclination that information should confirm what people already believe in order for it to not be considered fake news and that they are confident in recognizing misinformation when they see it. To varying degrees, education, age, gender and race also influenced individuals’ assessments of the importance of certain news cues and confirmation bias, as well as the strength of their confidence in their own ability to identify misinformation.

Research into demographics and fake news perceptions is important because although previous studies indicate strong ties between partisanship and political misinformation (Nyhan & Reifler, 2010; Weeks & Garrett, 2014), particularly in online spaces like Twitter (Brummette, DiStaso, Vafeiadis & Messner, 2018), relatively less attention has been given to the influence of other demographic variables even as some have argued about the ways in which disinformation can radicalize people along race and gender lines (Johnson, 2018).

Literature Review

Identifying Demographics as Key Variables

As the key independent variables in this study, demographics are important because they can be the foundation of our identities; how we see ourselves influences how we view everything in the world around us. Social identity theory helps explain how self-perceived membership in social groups—like race/ethnicity, gender, and political ideology, among others—affects our perceptions and behavior (Tajfel & Turner, 1986). In seeking to understand and define ourselves, we foster a sense of connectedness to others whom we see as being like us; we favor in-group members and tend to focus on the differences of the out-group (Tajfel & Turner, 1986). Demographics are our core personal identities (Perloff, 1996), and “people have…social distance between themselves and other persons based on their social positions or demographics, including age, gender, ethnicity, and education” (Go, Jung & Wu, 2014, p. 359). Individuals have multiple layers of identities, with some identities taking precedence over others in given situations to form a complex fabric that flexes and stretches based on personal preference and need.

In particular, social identity is a fundamental component of political partisanship that can influence how information is perceived across a multitude of topics (Greene, 2004). As noted, we hold stronger connections to some identities than others and there can be an interplay between our identities as Magnum (2013) found that racial identity can influence political identity. Other studies of demographics and social identity theory have shown that gender informs how we see ourselves and others (Cameron & Lalonde, 2001; Lindeman & Sundvik, 1995), that income plays a role in self-perception and connections with similar others (Martinangeli & Martinsson, 2020), and that educational experiences are often the foundation of our professional identities (Khalili, Orchard, Laschinger & Farah, 2013; Ma, Ma, Liu & Lassleben, 2020; Whitaker, 2020). The present research, then, uses social identity theory as the lens through which its findings are viewed as a way to interpret the role and importance of demographics in understanding perceptions about news cues, confirmation bias, and confidence in identifying fake news.

Looking for Cues of Fake News

The first goal of this study was to explore features in online material that individuals may rely upon to help them identify misinformation. These features— called news cues—include headlines, photos, links within stories, shareability, and objectivity that were identified in previous research (e.g. Go, Jung & Wu, 2014; Sundar, Knobloch-Westerwick & Hastall, 2007) for their important role in signaling to consumers the accuracy of associated information. News cues help consumers manage information overload by triggering mental shortcuts that make it easier for them to decide whether to further pursue the information they are presented with by continuing to read or otherwise engage with it (Sundar, Knobloch-Westerwick & Hastall, 2007). As users judge the credibility of the news cues, they process the features in the context of how the cues relate to them: Kessler & Engelmann (2019) found that news relevant to an individual’s social group appeals to that person’s social identity and reactivates knowledge about the topic. Because their interest in the information is based upon news cues that convey a consumer’s potential connection to the material, the individual might draw from their prior knowledge or engage in personal research to further determine the veracity of the information.

Since news cues influence users’ perceptions of a news story, it is particularly relevant as journalists struggle to help their audience differentiate legitimate reporting from fake news. The present study builds upon previous pieces that theorized news cues to be critical factors in fake news assessments (Jun et al., 2017; Tandoc et al., 2018a; Tandoc et al., 2018b) by examining the influence of demographics on news consumers’ assessments about their reliance on news cues when determining whether news material contains misinformation.

Recent research has examined single cues such as headlines, story source or objectivity in the context of misinformation perceptions and political ideology (Bago, Rand & Pennycook, 2020; Edgerly & Vraga, 2020; Mourao & Robertson, 2019; Schaffner & Roche, 2017), while other studies did not look at demographic data in their analysis of news cues. For example, Smelter and Calvillo (2020) discovered a link between the presence of photos and perceived accuracy of headlines, and Kim and Dennis (2019) studied the role of authors and headlines in credibility ratings. One study of science misinformation found that photos affected readers’ perceptions of the evidence presented in the article (Dixon, McKeever, Holton, Clarke & Eosco, 2015), and another noted that knowing the source of the story influenced perceptions of bias (Chia & Cenite, 2012). Greater scrutiny of news consumers’ reliance on multiple news cues and their various demographic variables can reveal expanded nuance in understanding what drives perceptions of misinformation as informed by social identity theory.

Similarly, consulting previous studies about how misinformation spreads offers valuable insight about the importance of accounting for news consumers’ age, gender, race, education and political ideology. Strong partisan beliefs are associated with selectively sharing misinformation and other types of biased reports online (Colleoni, Rozza & Arvidsson, 2014; Hopp, Ferucci & Vargo, 2020; Shin & Thorson, 2017), although Guess, Nagler and Tucker (2019) found age to be an even stronger determinant of disseminating fake news.

To help clarify the influence of demographic variables on news consumers’ perceptions of the importance of a variety of potential fake news signals, RQ1 is posed: To what extent do demographic variables predict the public’s reliance on news cues when identifying fake news?

Using Confirmation Bias in Evaluating News

In addition to examining the predictive effect of demographics when relying on news cues to determine whether a story contains misinformation, this research also looks at the connection between demographics and preferring information that validates what an individual already believes as they are assessing potential fake news.

Other studies employing social identity theory to examine confirmation bias—favoring information that reinforces what one already believes—found that people will seek out material from sources they perceive as being in-group and assign greater credibility to information if they perceive accepting it bolsters their membership in the group (Attwell, Smith & Ward, 2018; Go, Jung & Wu, 2014). Thus, analyzing the influence of people’s social identities as they relate to race, gender and political ideology among other demographic variables can shed light on how confirmation bias functions in regard to fake news assessments.

People tend to gravitate toward attitude-consistent information (Winter, Metzger, & Flanagin, 2017), which may be exacerbated by partisan information sources (Tripodi, 2018; Zompetti, 2019). Previous research on this topic, as with news cues, centers on the influence of partisan ideology. Confirmation bias can impact judgments about the credibility of news and news organizations on both ends of the political ideology spectrum (Mourao & Robertson, 2019; Tong, Gill, Li, Valenzuela & Rojas, 2020; Van Duyn & Collier, 2019). News consumers with strong political beliefs tend to spend more time with media sources that support and reinforce their views (Kaye & Johnson, 2016). Brummette et al. (2018) warned of online echo chambers because people are repeatedly exposed to messages decrying oppositional information as “fake news” simply because it comes from a different political party or party member. Such chambers are self-perpetuating as individuals connect in online spaces with others who share their views and are perceived as being in-group, increasing the likelihood of selective exposure to information they already believe is accurate and true (Tripodi, 2018; Winter, Metzger, & Flanagin, 2017). This phenomenon, as Nelson and Taneja (2018) explained, compounds the difficulty journalists face in persuading “audiences that real news is more credible—even when it tells them things that run counter to how they would like the world to be” (p. 3734).

At least two other demographic variables may influence engaging in selective exposure and fueling confirmation bias: Race and gender also can be factors in seeking out information that reinforces beliefs, as noted in Johnson’s (2018) conclusion that repeated fake news appeals and accusations on social media function to radicalize some white men as they seek to find others who are “like” them.

These findings lead to RQ2: To what extent do demographic variables predict the public’s reliance on confirmation bias when identifying fake news?

Developing Confidence in Identifying Fake News

Confidence is a crucial element in suppressing the spread of misinformation, which otherwise fuels confusion, mistrust and partisanship (Nyilasy, 2019). Individuals develop confidence in their ability to identify misinformation through a tenuous progression in which incongruous data can undermine their certainty (Burke, 2010). While some research has focused on how individuals fact-check in social media spaces (Jun, Meng, & Johar, 2017; McNair, 2017; Wenzel, 2019) and Van Duyn and Collier (2019) found that increased exposure to fake news is associated with diminished accuracy in identifying real news, relatively little work has been done to understand the potential impact of social identity theory and demographic variables on people’s confidence in their ability to recognize fake news.

What we do know about confidence is that it involves complex information processing (Chaxel, 2016) which is intricately dependent on the person analyzing the issue and gaining knowledge until they feel secure in their skills to handle it (Wan & Rucker, 2013). Information is processed in different methods based on how confident the individual is about the strength of the argument they’re considering and how relevant it is to their life (Wan & Rucker, 2013). The more relevant the information is to a person, the greater the depth of their cognitive processing. Confidence also is linked to identity management because new information can threaten any number of identities an individual holds, especially if it’s seen as a direct challenge to a particularly salient identity (Martiny & Kessler, 2014). Individuals whose demographic details are tightly bound to their sense of identity may rely more heavily, for example, on their political ideology or gender identity to help them assess information in the context of what they think their group believes and develop confidence that those evaluations are accurate. Thus, information that disputes “truth” as recognized through a group identity might affect confidence in regard to belonging to the group as well as the ability to effectively identify fake news.

In one of the few studies on confidence and misinformation, Schwarzenegger (2020) found that news consumers with higher confidence believed they could better differentiate between truthful and fake news than could people with lower confidence. Similarly, individuals with greater confidence in their news literacy are more skeptical of misinformation when they encounter it online (Paisana, Pinto-Martinho & Cardoso, 2020).

Because lower confidence in identifying misinformation undermines informed analysis, RQ3 asks: To what extent do demographic variables predict the public’s confidence in their own ability to identify fake news?

Methodology

Similar to other studies examining perceptions of misinformation (e.g. Bathel et al. 2016; Tandoc et al., 2018b), an online survey was developed to answer the research questions. Pretests were conducted with a convenience sample of 20 adults ranging in age from 21 to 70 to ensure the reliability of question wording and response measures, all of which were drawn from previous research as detailed below.

With internal funding for this study from a university grant, the survey firm Qualtrics was contracted to recruit respondents from its national pool of survey participants in October 2017. Requirements for the present study included that all participants were at least 18 years old and had one or more social media accounts. Each participant received under $5 for a completed survey from Qualtrics, and survey-takers certified at the start of the questionnaire that they would provide true and honest responses. Data was collected from 553 participants, and the sample was weighted to control for a greater number of female participants (n=390, 70.7%). The weighted sample yielded a more even gender breakdown, with 50.6% female (n=390) and 49.4% male (n=381) for a total weighted n of 771. Other demographic data from the weighted sample is generally representative of the U.S. adult population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2019), and further demographic data is provided below.

Demographic Overview of Participants

Participants split fairly evenly into three groups of political ideology: 37.1% (n=286) indicated they were on the liberal spectrum, 30.8% (n=237) identified as conservatives, and the remaining 32.1% (n=247) identified as neither liberal nor conservative. Their ages ranged from 18 to 84, with 25% (n=193) being 18-29, 37.2% (n=287) were 30-49, 22.5% (n=173) were 50-64, and 15.3% (n=118) were 65 and older. More than three-quarters (76.5%) of the participants were White or Caucasian (n=589). About one-quarter (n=193, 25.1%) had high school as their highest education level, 55.9% (n=431) had some college or had graduated with a bachelor’s degree, and 15.8% (n=122) had some graduate education or had earned a graduate or professional degree.

Measures

Independent Variables: Demographics

The independent variables in each RQ are the demographic factors. For age, survey participants were asked to enter their current age as a whole number. Gender options were either male or female. Participants selected their race from seven choices: Black or African-American, White or Caucasian, Hispanic or Latino, Asian or Asian-American, Native American, multiple races, or other. In order to run the regression analysis, the categories were collapsed into two groups: White and all others. To indicate their highest level of education, participants chose from eight options: less than high school, high school, some college, bachelor’s degree, some graduate education, professional certificate, master’s degree, and doctoral degree. Finally, in regard to political ideology, participants were asked to choose where they would place themselves on a scale that included: very liberal, somewhat liberal, closer to liberal, neither liberal or conservative, closer to conservative, somewhat conservative, and very conservative.

Dependent Variables: Fake news cues

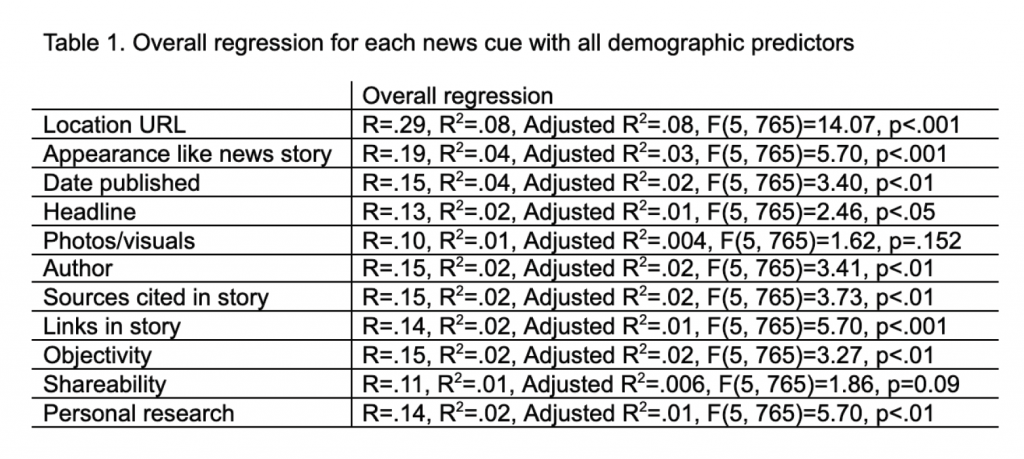

RQ1 examines 11 cues that participants might look for when trying to determine if a news story contains fake news. The survey presented them with a variety of features theorized in other work as being factors in identifying fake news, such as scrutinizing the headline, sources, visuals and shareability of the story, as well as trying to find the same information on their own from a different source (Jun et al., 2017; Tandoc et al., 2018a; Tandoc et al., 2018b). Table 1 displays a complete list of the news cues. Participants noted on a seven-point semantic differential scale the frequency with which they rely on the features (1=Never to 7=Extremely often).

Dependent Variable: Confirmation bias

The dependent variable in RQ2 is based on research that indicates people prefer information that supports beliefs they already hold so as to not create cognitive dissonance (Westerwick, Johnson, & Knobloch-Westerwick, 2017; Winter, Metzger, & Flanagin, 2017). Participants used a seven-point semantic differential scale (1=Not important to 7=Very important) to indicate the importance of a news story confirming what they already believe when they are deciding whether it contains fake news.

Dependent Variable: Confidence in Identifying Fake News

The dependent variable in RQ3 is the participants’ confidence in their ability to identify misinformation. They were not primed in the survey with specific examples of mis- or disinformation because, as Fletcher and Nielsen (2018) found, the public broadly understands “fake news” but does not wade into categorical distinctions. To avoid confusion, participants were asked how confident they are in their ability to recognize news that is made up, which mirrors a similar question asked by Barthel et al. (2016) in a Pew study. Responses on a seven-point semantic differential scale ranged from Not at all confident (1) to Very confident (7).

Results

Fake News Cues

With RQ1, this study asked “To what extent do demographic variables predict the public’s reliance on news cues when identifying fake news?” as it sought to empirically examine concepts theorized in other studies (Jun et al., 2017; Tandoc et al., 2018a; Tandoc et al., 2018b) that suggested the news audience looks for particular cues when determining whether an article contains misinformation. Those cues include headlines, visuals, links within stories, sources cited in stories, and date published. In addition, other news cues examined in this study included how frequently participants reported relying on their own assessments of objectivity and conducting personal research. Because of the number of independent and dependent variables involved in analyzing this research question, an individual regression test was run for each news cue to determine the influence of the demographic variables on it. In answering RQ1, the present study found that of the 11 news cues, nine had statistically significant overall regressions, which are listed in Table 1 and indicate small but significant relationships between some of the variables. The significant regressions showed demographics help predict reliance on the following news cues when determining the presence of misinformation: location URL, appearance like a news story, date published, headline, author, sources cited within story, links in the story, objectivity and personal research.

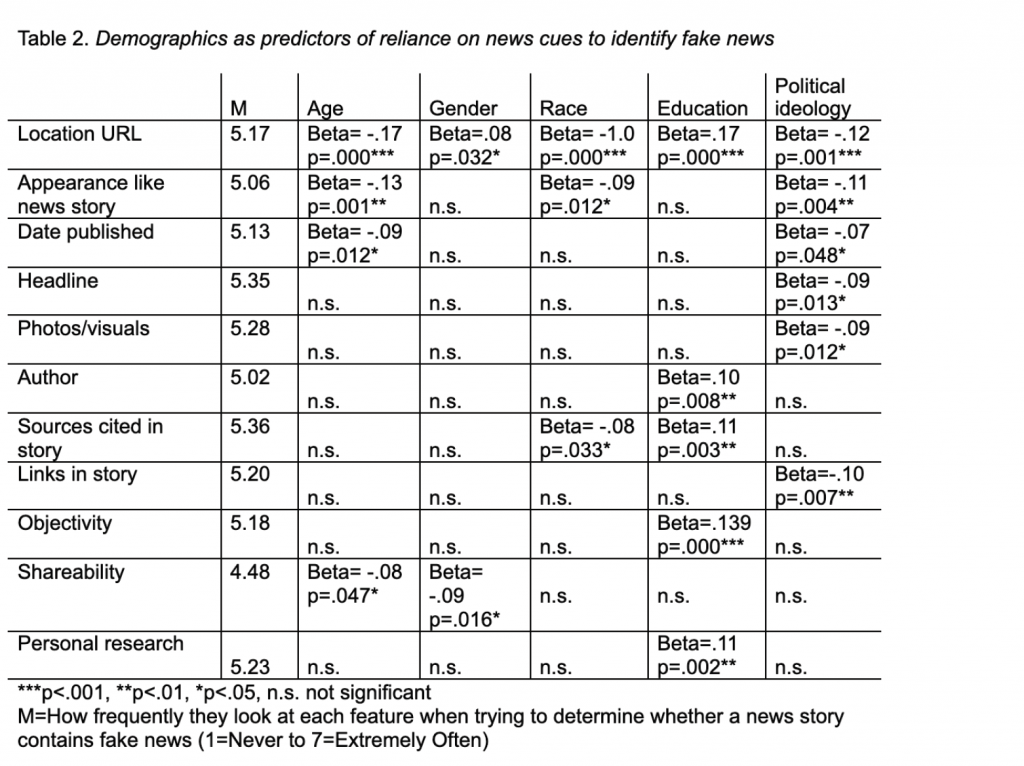

To add greater detail in answering RQ1, Table 2 presents the statistically significant regression details for each news cue and participants’ demographics. Political ideology was a statistically significant factor in six features, with participants who were more liberal reporting they more frequently relied on examining the URL, story appearance, headline, visuals, date published and links when trying to determine whether news stories contain fake news.

Education level also was a significant influence, with more highly educated individuals reporting they spend more time conducting research on their own and assessing an article’s objectivity, as well as contemplating the piece’s URL, author and sources.

Age, too, played a role in the reliance on looking to certain cues: Younger people said they more frequently use the story’s URL, appearance, publication date and shareability as indicators of whether the material might present misinformation.

White participants indicated they more frequently consult the URL, appearance and sources cited. Women said they look at story URLs more often than men, and men indicated they look for shareability options more frequently than women.

Taken together, only the URL of the story was significant across the five demographic variables, and the appearance of the information as looking like a news story was significant in three of the demographic variables. The remaining news cues were significant in only one or two demographic variables, suggesting much work is to be done to improve recognition of these features as keys to identifying misinformation.

Confirmation Bias

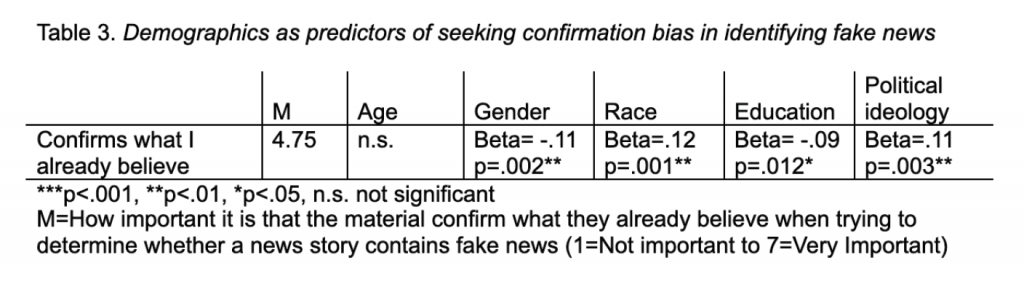

To better understand the role of confirmation bias in fake news assessments, RQ2 posed the question: “To what extent do demographic variables predict the public’s reliance on confirmation bias when identifying fake news?” The desire for confirmation bias was compared across the five demographic variables as predictors, and the overall regression was statistically significant, R=.21, R2=.05, Adjusted R2=.04, F(5, 765)=7.34, p<.001, with small relationships between the variables.

Table 3 presents the statistically significant regression findings. Confirmation bias had several drivers, with the following demographic variables indicating that having information confirm what they already believe was of great importance to them: being male, non-White, less educated and more conservative. That confirmation bias was significant in four of the five demographic variables indicates that certain individuals’ identities may influence their desire for information that does not challenge what they perceive their in-groups believe to be true.

Confidence in Identifying Fake News

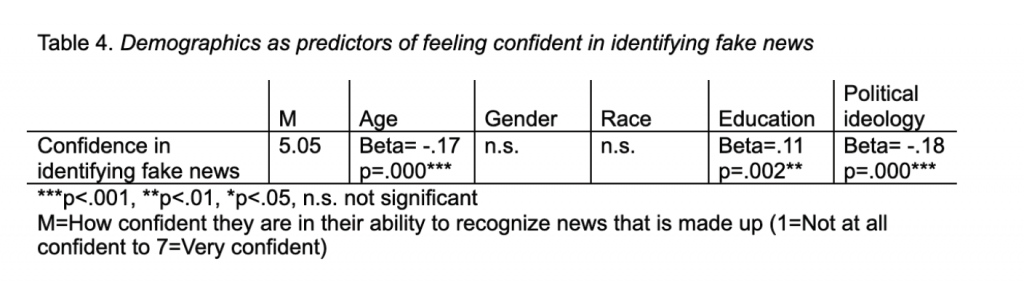

On a limited scale, previous research (e.g. Burke, 2010) has examined how people develop confidence in identifying misinformation but there is no known research on the influence of an individual’s education, age and other demographics on feeling confident in their own ability to recognize fake news. RQ3 investigated the ability of demographic variables to predict personal confidence in identifying news that is made up by asking, “To what extent do demographic variables predict the public’s confidence in their own ability to identify fake news?” The overall regression with all five predictors was statistically significant, R=.30, R2=.09, Adjusted R2=.08, F(5, 765)=15.17, p<.001, though the relationships between the variables were small.

Table 4 shows the statistically significant regression findings. Political ideology, age, and education were significant influences, with people who were younger, more liberal and more educated being more confident in recognizing misinformation. This finding rises in stark contrast to the demographic identities of those who reported for RQ2 that they rely on information that confirms what they already believe and is discussed in the next section.

Discussion

As recent events like the U.S. presidential elections of 2016 and 2020 and the COVID-19 pandemic have shown, fighting misinformation can seem insurmountable. This study sought to develop a better understanding of how individuals’ demographics influence their perceptions about misinformation. Specifically, this research examined how age, race, gender, education and political ideology impact people’s assessments about fake news related to 1) their reliance on cues like headlines and visuals, 2) the extent to which they believe information should confirm what they already believe, and 3) their confidence in their own ability to identify misinformation. Although a growing body of literature (e.g. Bago, Rand & Pennycook, 2020; Brummette, DiStaso, Vafeiadis & Messner, 2018; Edgerly, Mourao, Thorson & Tham, 2020; Hopp, Ferucci & Vargo, 2020; McNair, 2017; Mourao & Robertson, 2019; Tandoc et al., 2018a; Tong et al., 2020) examines news audiences’ experiences with various forms of misinformation, it rarely takes a close look at the role of multiple demographics and how those identities influence the ways in which people assess news. By filling this gap, the present study uses empirical data to highlight the importance of understanding how our social identities can inform what we see as credible cues of legitimate news, why certain groups of individuals may seek out information that confirms what they already believe, and why other groups report feeling more confident in their ability to identify fake news.

Social identity theory helps explain how we make sense of our many identities—which includes how we see ourselves as belonging to certain demographic groups and seeking to maintain connections to those groups (Go, Jung & Wu, 2014; Perloff, 1996). In this study, social identity theory aids in interpreting the findings so more effective news literacy strategies can be developed—particularly in relation to education and political ideology since those variables were significant predictors in each research question.

The sustained influence of education in the regression analyses suggests it could be one of the most important factors in bridging partisan ideologies as individuals assess news. Education was the only demographic variable to have a significant influence on two key news cues: evaluating objectivity and conducting personal research. Previous studies have shown that news audiences still struggle to identify objective news (Urban & Schweiger, 2014) and that performing research on their own requires extra cognitive effort that people are generally not inclined to undertake (Edgerly, Mourao, Thorson & Tham, 2020). Better education in the form of repeated news literacy training could help to build research skills and an appreciation for objectivity, which carries a trickle-down influence on several of the news cues because those literacy programs stress looking to features like headlines and sources cited when verifying accuracy and objectivity (Urbani, 2019). That younger people showed greater frequency in looking at certain news cues suggests the effectiveness of recent concerted efforts to boost media literacy skills in K-12 education and at some higher education institutions, as well as through public materials developed by nonprofits, libraries and media organizations. Social identity theory suggests that one possible way to boost older adults’ reliance on news cues is to focus on incorporating more people from their perceived in-group (other older adults) to help educate them about which features they can trust as credible indicators of legitimate news.

Of concern is that people who identify as more liberal and as having more education look to several news cues more frequently than conservatives and those with less education when they are assessing whether the material contains misinformation—the concern is that people who identify as more conservative and as having less education are not looking to news cues at the same rate. It’s possible that an explanation for this phenomenon can be found in confirmation bias. People who were more conservative and less educated also reported feeling it was important to have information confirm what they already believe when trying to determine if the material contains fake news. Through social identity theory, it could be that the demographic identities of people who are more conservative and less educated are tightly bound in finding information that they believe represents the views of their in-group and are less concerned with the credibility cues they could independently ascertain from features like URLs, headlines and photos. The draw to be “like” others with whom we identify is a powerful psychological motivator that can lead individuals to dismiss oppositional information and seek data that supports what the group believes to be true (Tripodi, 2018; Winter, Metzger, & Flanagin, 2017). To combat this, it will be crucial to recruit people who are viewed as in-group to encourage individuals who are more conservative and less educated to see the value in relying on news cues to determine whether a news story contains misinformation instead of more readily dismissing material that might challenge what they believe to be true.

Similarly, people who were more liberal and had more education were more likely to be confident in their ability to identify fake news. Understanding the function of identity in social group membership may help to develop new strategies that will engage conservatives and those with less education in becoming more confident. Since these groups relied more heavily on confirmation bias when determining if a story contained fake news, it’s possible they were less concerned with whether they felt confident in identifying misinformation and instead relied more on how they perceived their in-group to assess fake news. Further research using experimental design can begin to investigate these potential relationships.

As with all research, this study has limitations and points to several avenues for future research. Among the limitations are that the data was weighted to balance the greater number of female participants in the survey and that because of lower numbers in some of the seven race categories, the groups had to be collapsed into two options (White and non-White) in order to run the statistical analyses. These necessary decisions may have led to decreased nuance in assessing how these demographic factors can be small but significant predictors of evaluating certain news cues and relying on confirmation bias when determining whether news contains misinformation.

Moving forward, another survey-based project could use a larger sample of participants with a more even demographic spread and test the reliance on social media as a news source against the variables already included in this study. Additional research could examine the interaction of the news cues and a preference for confirmatory information that was suggested in Moravec, Minas and Dennis (2019) and it could create a model to examine the interactions of the demographic variables on each other as the independent variables are added. Using experimental design, researchers could test different news cues (headlines, story URLs, etc.) in news stories and social media posts to learn which wording and visuals trigger “fake news” judgments.

Conclusions

Circling back to the Pew report mentioned in the introduction and the “complicated relationship” Americans have with the media (Gottfried, Walker & Mitchell, 2020, para. 1), this research confirmed some of the strain on that relationship might be attributed in a small but significant way to the demographic background of the public and their reliance on certain cues to signal that articles might contain fake news. It also confirmed that certain demographics are a factor in many Americans’ tendency to prefer confirmatory information and that our confidence in identifying misinformation is tied to age, education and political ideology. But simply knowing these things won’t help change that a considerable swath of Americans don’t trust news or the journalists who produce it.

So how can this data help journalists and other groups fight misinformation? The present research helps identify what journalists and educators can work on, based on the characteristics of who’s looking at certain cues—and who isn’t. This project reinforces previous findings that partisanship is real (Tripodi, 2018; Zompetti, 2019) and it affects behavior in terms of relying on certain cues and seeking out confirmatory information (Bago, Rand & Pennycook, 2020; Edgerly & Vraga, 2020; Kaye & Johnson, 2016). It indicates that education and age are also important considerations in devising strategies to help the public become better at evaluating information and recognizing fake news. Knowing about the influence of demographics matters because it enables us to bring those characteristics together and combine them with other pieces of information that can work in tandem to, as boyd (2017) explained, “develop social, technical, economic, and political structures that allow people to understand, appreciate, and bridge different viewpoints” (para. 23).

News literacy education can alleviate the pull of partisan information by providing people with better tools to evaluate the veracity of material and look beyond whether it reinforces their existing beliefs. It is not reasonable to expect people to “overcome” being conservative or liberal because those ideologies may be central to their identity—but we can use news literacy education to give people greater access to developing the skills to recognize balanced, valid arguments in the different viewpoints that are presented in news articles and other forms of information by talking to them through individuals they perceive as credible in-group members. In recognizing the value of the totality of facts around an issue, it can lessen problematic extremist positions and assuage perceived threats to individuals’ partisan identities (Schaffer & Roche, 2017). Taken together, these experiences could bolster news consumers’ confidence in identifying misinformation.

The central takeaways from this research are that demographics—particularly age, education and political ideology—do influence our experiences with journalism and perceptions about misinformation. Understanding how identity informs which news cues people rely on when they’re trying to determine if a news article contains misinformation can help journalists develop strategies to draw attention to cues that are important but overlooked by some news consumers and assist news professionals in better engaging with their audience. The demographic data here provides clearer detail about which areas need greater focus in the effort to help people become more critical consumers of news and information and better learn which cues can signal credibility. Starting from the foundation of utilizing authoritative in-group members to teach about the importance of assessing multiple news cues, we can hope to use news literacy education to lessen people’s tendency to gravitate toward information that confirms what they already believe when they’re evaluating potential fake news—especially among those whose demographic variables indicated a heavier preference for such confirmation. Ideally, news literacy knowledge will inspire greater confidence across age, race, gender, education and political ideology in identifying misinformation and disrupt the cycle of partisanship that is an overwhelming detriment to the critical analysis of factual reasoning, verification through impartial data and the recognition of objectivity.

References

Attwell, K., Smith, D. T., & Ward, P. R. (2018). ‘The Unhealthy Other’: How vaccine rejecting parents construct the vaccinating mainstream. Vaccine, 36(12), 1621–1626.

Bago, B., Rand, D. G., & Pennycook, G. (2020). Fake news, fast and slow: Deliberation reduces belief in false (but not true) news headlines. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 149(8), 1608–1613.

Barthel, M., Mitchell, A. & Holcomb, J. (2016, December 15). Many Americans believe fake news is sowing confusion. Pew Research Center. http://www.journalism.org/2016/12/15/many-americans-believe-fake-news-is-sowing-confusion/

boyd, danah. (2017, March 27). Google and Facebook can’t just make fake news disappear. Wired. https://www.wired.com/2017/03/google-and-facebook-cant-just-make-fake-news-disappear

Brummette, J., DiStaso, M., Vafeiadis, M., & Messner, M. (2018). Read all about it: The politicization of “fake news” on Twitter. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 95(2), 497-517.

Burke, S. J. (2010). The impact of confidence in evaluating on discounting: A missing information example. Journal of Consumer Behavior, 9(5), 333-348.

Cameron, J. E., & Lalonde, R. N. (2001). Social identification and gender-related ideology in women and men. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40(1), 59-77.

Chaxel, A. S. (2016). Why, when and how personal control impacts information processing: A framework. Journal of Consumer Research, 43(1), 179-197.

Chia, S., & Cenite, M. (2012). Biased news or biased public? Journalism Studies, 13(1), 124–140.

Colleoni, E., Rozza, A., & Arvidsson, A. (2014). Echo chamber or public sphere? Predicting political orientation and measuring political homophily in Twitter using big data. Journal of Communication, 64(2), 317–332.

Dixon, G. N., McKeever, B. W., Holton, A. E., Clarke, C., & Eosco, G. (2015). The power of a picture: Overcoming scientific misinformation by communicating weight-of-evidence information with visual exemplars. Journal of Communication, 65(4), 639–659.

Edgerly, S. & Vraga, E. K. (2020). That’s not news: Audience perceptions of “news-ness” and why it matters. Mass Communication and Society, 23(5), 730–754.

Edgerly, S., Mourão, R. R., Thorson, E., & Tham, S. M. (2020). When do audiences verify? How perceptions about message and source influence audience verification of news headlines. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 97(1), 52–71.

Fletcher R., & Nielsen R. K. (2018). Are people incidentally exposed to news on social media? A comparative analysis. New Media & Society, 20(7), 2450–2468.

Go, E., Jung, E. H., & Wu, M. (2014). The effects of source cues on online news perception. Computers in Human Behavior 38, 358–367.

Gottfried, J., Walker, M., & Michell, A. (2020, August 31). Americans see skepticism of news media as healthy, say public trust in the institution can improve. Pew Research Center. https://www.journalism.org/2020/08/31/americans-see-skepticism-of-news-media-as-healthy-say-public-trust-in-the-institution-can-improve/

Greene, S. (2004). Social identity theory and party identification. Social Science Quarterly, 85(1), 136–153.

Guess, A., Nagler, J., & Tucker, J. (2019). Less than you think: Prevalence and predictors of fake news dissemination on Facebook. Science Advances, 5(1), 1–8.

Hopp, T., Ferucci, P., & Vargo, C. J. (2020). Why do people share ideologically extreme, false, and misleading content on social media? A self-report and trace data-based analysis of countermedia content dissemination on Facebook and Twitter. Human Communication Research, 46(4), 357–384. https://doi. org/10.1093/hcr/hqz022

Johnson, J. (2018). The self-radicalization of White men: “Fake news” and the affective networking of paranoia. Communication, Culture & Critique, 11(1), 100–115.

Jun, Y., Meng, R., & Johar, G. V. (2017). Perceived social presence reduces fact-checking. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 114(23), 5976–5981.

Kaye, B. K., & Johnson, T. J. (2016). Across the great divide: How partisanship and perceptions of media bias influence changes in time spent with media. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 60(4), 604–623.

Kessler, S. H., & Engelmann, I. (2019). Why do we click? Investigating reasons for user selection on a news aggregator website. Communications: The European Journal of Communication Research, 44(2), 225–247.

Khalili, H., Orchard, C., Laschinger, H. K. S., & Farah, R. (2013). An interprofessional socialization framework for developing an interprofessional identity among health professions students. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 27(6), 448–453.

Kim, A., & Dennis, A. R. (2019). Says who? The effects of presentation format and source rating on fake news in social media. MIS Quarterly, 43(3), 1025–1039.

Lindeman, M., & Sundvik, L. (1995). Evaluative bias and self-enhancement among gender groups. European Journal of Social Psychology, 25(3), 269–280.

Ma, B., Ma, G., Liu, X., & Lassleben, H. (2020). Relationship between a high-performance work system and employee outcomes: A multilevel analysis. Social Behavior & Personality: An International Journal, 48(1), 1–9.

Magnum, M. (2013). The racial underpinnings of party identification and political ideology. Social Science Quarterly, 94(5), 1222–1244.

Martinangeli, A. F. M., & Martinsson, P. (2020). We, the rich: Inequality, identity and cooperation. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 178, 249–266.

Martiny, S. E., & Kessler, T. (2014). Managing one’s social identity: Successful and unsuccessful identity management. European Journal of Social Psychology, 44(7), 748–757.

McNair, B. (2017). Fake news: Falsehood, fabrication, and fantasy in journalism. Routledge.

Moravec, P. L., Minas, R. K., & Dennis, A. R. (2019). Fake news on social media: People believe what they want to believe when it makes no sense at all. MIS Quarterly, 43(4), 1343–1360.

Mourão, R. R., & Robertson, C. T. (2019). Fake news as discursive integration: An analysis of sites that publish false, misleading, hyperpartisan and sensational information. Journalism Studies, 20(14), 2077–2095.

Nelson, J. L., & Taneja, H. (2018). The small, disloyal fake news audience: The role of audience availability in fake news consumption. New Media & Society, 20(10), 3720–3737.

Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2010). When corrections fail: The persistence of political misperceptions. Political Behavior, 32(2), 303–330.

Nyilasy, G. (2019) Fake news: When the dark side of persuasion takes over. International Journal of Advertising, 38(2), 336–342.

Paisana, M., Pinto-Martinho, A., & Cardoso, G. (2020). Trust and fake news: Exploratory analysis of the impact of news literacy on the relations with news content in Portugal. Communication & Society 33(2), 105–117.

Perloff, R. M. (1996). Perceptions and conceptions of political media impact: The third-person effect and beyond. In A. N. Crigler (Ed.), The psychology of political communication (pp. 177–197). University of Michigan Press.

Schaffner, B. F., & Roche, C. (2017). Misinformation and motivated reasoning. Public Opinion Quarterly, 81(1), 86–110.

Schwarzenegger, C. (2020). Personal epistemologies of the media: Selective criticality, pragmatic trust, and competence-confidence in navigating media repertoires in the digital age. New Media & Society, 22(2), 361–377.

Shin, J., & Thorson, K. (2017). Partisan selective sharing: The biased diffusion of fact-checking messages on social media. Journal of Communication, 67(2), 233–255.

Smelter, T. J., & Calvillo, D. P. (2020). Pictures and repeated exposure increase perceived accuracy of news headlines. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 34(5), 1061–1071.

Sundar, S. S., Knobloch-Westerwick, S., & Hastall, M. (2007). News cues: Information scent and cognitive heuristics. Journal of the American Society of Information Science and Technology, 58(3), 366–378.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel & W. G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relation (pp. 7–24). Hall Publishers.

Tandoc, E. C., Lim, Z. W., & Ling, R. (2018a). Defining “fake news:” A typology of scholarly definitions. Digital Journalism, 6(2), 137–153.

Tandoc, E. C., Ling, R., Westlund, O., Duffy, A., Goh, D., & Lim, Z. W. (2018b). Audiences’ acts of authentication in the age of fake news: A conceptual framework. New Media & Society, 20(8), 2745–2763.

Tong, C., Gill, H., Li, J., Valenzuela, S., & Rojas, H. (2020). ‘Fake News Is Anything They Say!’ Conceptualization and weaponization of fake news among the American public. Mass Communication and Society, 23(5), 755–778.

Tripodi, F. (2018). Searching for alternative facts: Analyzing scriptural inference in conservative news practices. Data & Society Research Institute. https://datasociety.net/library/searching-for-alternative-facts/

Urban, J., & Schweiger, W. (2014). News quality from the recipients’ perspective. Journalism Studies, 15(6), 821–840.

Urbani, S. (2019, October 14). Verifying online information: The absolute essentials. First Draft. https://firstdraftnews.org/latest/verifying-online-information-the-absolute-essentials/

U.S. Census Bureau. (2019, July 1). Quick facts. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219

Van Duyn, E., & Collier, J. (2019). Priming and fake news: The effects of elite discourse on evaluations of news media. Mass Communication and Society, 22(1), 29–48.

Wan, E. W., & Rucker, D. D. (2013). Confidence and construal framing: When confidence increases versus decreases information processing. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(5), 977–992.

Weeks, B. E., & Garrett, R. K. (2014). Electoral consequences of political rumors: Motivated reasoning, candidate rumors, and vote choice during the 2008 U.S. presidential election. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 26(4), 401–422.

Wenzel, A. (2019). To verify or disengage: Coping with ‘fake news’ and ambiguity. International Journal of Communication, 13, 1977–1995.

Westerwick, A., Johnson, B. K., & Knobloch-Westerwick, S. (2017). Confirmation biases in selective exposure to political online information: Source bias v. content bias. Communication Monographs, 84(3), 343–364.

Whitaker, M. C. (2020). Us and them: Using social identity theory to explain and re-envision teacher-student relationships in urban schools. Urban Review, 52(4), 691–707.

Winter, S., Metzger, M., & Flanagin, A. (2017). Selective use of news cues: A multiple-motive perspective on information selection in social media environments. Journal of Communication, 66(4), 669–693.

Zompetti, J.P. (2019). The fallacy of fake news: Exploring the commonsensical argument appeals of fake news rhetoric through a Gramscian lens. Journal of Contemporary Rhetoric, 9(3/4), 139–159.

Amber Hinsley, Ph.D. joined the faculty at Texas State in Fall 2020 after 10 years at Saint Louis University. Hinsley uses her experience as a former journalist to blend the instruction of journalism and multimedia skills in classes with her research, which currently focuses on misinformation related to news and health as well as journalists’ use of social media as professional tools. Her research has been published in a variety of academic journals including Journalism, Journalism Studies, Newspaper Research Journal, Journal of Radio and Audio Media, and Computers in Human Behavior.