Mapping digital-native U.S. Latinx news: Beyond geographical boundaries, language barriers, and hyper-fragmentation of audiences

By Jessica Retis and Lourdes M. Cueva Chacón

[Citation: Retis, J., & Cueva Chacón, L.M. (2021). Mapping digital-native U.S. Latinx news: Beyond geographical boundaries, language barriers, and hyper-fragmentation of audiences. #ISOJ Journal, 11(1), 35-63.]

In the post-digital era, Latinx journalists have encountered new spaces to communicate with bicultural and bilingual audiences in the United States. Seeking to fill a gap in the investigations about diversity in digital journalism, our research takes on the task of identifying these news media projects to advance the study of contemporary professional practices. This article presents preliminary findings of a larger research project that seeks to map digital-native U.S. Latino news media by examining their online content and their strategies to produce and disseminate information about Latinx communities. A review of 103 Latinx digital outlets revealed that most are very young, are present where Latinx populations are growing faster (i.e., Midwest), and almost half of them produce original content for more than one digital platform. Finally, these digital-natives see their mission as informing, amplifying, and elevating the discourse about Latinx communities and are boosting the development of Latinx diasporic transnational media spaces.

The rapid changing synergies of news production, distribution and consumption in the digital era have altered long-established journalism models. New journalism models have emerged in the American news media landscape during the digital and the now so-called post-digital era (Cramer, 2015). The expansion of the U.S. non-profit news sector since the mid-2000s was invigorated by funding from foundations and donors (Birnbauer, 2018). The rise and growth of crowd-funded journalism as a novel business model (Jian & Usher, 2014) has been examined as a result of a displacement from a mainstream media model to a more networked public sphere (Benkler, 2006). In the case of Latinx media, these new synergies require also thinking in terms of transnational and global flows and situating “diasporic cultures” in their midst, understanding them in terms of their relation to the complex ethnoscapes, financescapes, mediascapes, technoscapes, and ideoscapes that make up the global terrain and the networks that populate these (Appadurai, 1996; Tsagarousianou & Retis, 2019).

These rapid-changing scenarios require constant adaptations. For practitioners, these new contexts demanded revisiting the traditional ways of producing news while remaining profitable and keeping financing quality journalism (Chinula, 2017). For researchers, they required implementing critical forums for scholarly discussion and investigations about the wide-ranging implications of digital technologies for the practice and study of journalism (Franklin, 2013; 2014). In the realm of these ever-changing scenarios, Latino media outlets have encountered new spaces to communicate with bicultural and bilingual audiences in the United States and beyond. (In this essay, the terms Latino, Latina, and Latinx are used interchangeably to refer to people from Latin American descent. The researchers acknowledge that these terms are embraced and contested within the Latino communities and academia since they imply both common and diverse pan-ethnic experiences.)

Seeking to fill a gap in the investigations about diversity in digital journalism, our research project takes on the task of identifying new news media outlets to advance the study of contemporary practices. This article presents initial findings of a larger research project that seeks to map digital-native U.S. Latinx news media by examining their online content, their strategies to produce and disseminate information about Latinx communities as well as the way they interact with their audiences.

Literature Review

Latino Media in the American News Media Landscape

Examining demographic changes become essential to study the diverse nature and impact of Latinx in the American news media landscape. In 2020, 60.6 million Latinxs constituted 18.5% of the nation’s total population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020) and is projected to grow up to 106 million in 2050 (Krogstad, 2014). These growing patterns impact the emergence and development of information and communication needs. Latino media have been part of the American news media landscape for more than two centuries. Despite the trend to consider them mainly as ethnic or minority media, they have demonstrated to be part of the American public sphere—e.g., Spanish-language news casts have out-performed major English-language broadcast networks in primetime—(AP, 2019).

As media reflects the demographics, changes in their audiences influence their production/consumption synergies. If one takes a look at the history of Latino media, one can see that since the foundation of the first Spanish-language print newspaper, El Mississippí, in 1808, to the launching of Conecta Arizona, a Spanish-language daily stream of news to subscribers on WhatsApp, Facebook, and other social media platforms in May 2020, not only have 200 years passed, but also a series of transformations in the digital and social media world. But both then and now are news media ventures seeking to meet the needs for information and self-representation.

Latino news is a product of bilingual journalism practices that require bicultural competencies to gather, assess, present, and disseminate news and information about, or relevant to, Latinx communities. Offered in Spanish, English, or bilingually, Latino media engages with the understanding of current affairs, but also the history, economics, politics, and culture of diverse groups, whether U.S.-born or immigrants, as well as their global liaisons with countries where they trace their origins (Retis, 2021). Following the complex nature of the Latinx groups in the United States, the media they produce are not a monolith but reflect the vast and deep differences between the communities they serve (Aguilera, 2020). Just as there is no such thing as the “Latino vote” (Rakich & Thomson-DeVeaux, 2020), U.S. Latino media is made up of a myriad of different types of outlets. The larger research project in which this article is based seeks to desegregate the complex components that make up the digital Latino media interactions in the American digital journalism ecology. It seeks to dismantle the tendency to homogenize Latinx communities and, consequently their mediascapes by constructing an interdisciplinary perspective that helps understand the complex, diverse, and constantly changing dynamics of Latinx communities living in a highly mediated transnational life and their media and communication practices (Retis, 2019a).

As argued elsewhere, the political economy of the media and sociology of newsmaking theoretical approaches help us understand how, throughout their more than two centuries of life, Latino news outlets’ editorial profile has ranged from politically conservative to liberal and reflected the status of their audiences as exiles, refugees, immigrants or U.S.-born Latinxs. Ownership has varied from private to non-commercial, from subsidized enterprises to community-based projects, from U.S. Latino initiatives to Latin American foreign investment ventures. Latino news coverage has ranged from local to regional, national, international, transnational, and even translocal. An advocate for immigrants marginalized by discriminatory political, linguistic, and cultural policies in their beginnings, Latino news media today serves growing communities of Latinx people born in the United States and abroad, educated in English, and speaking Spanish at home (Retis, 2019b).

The way in which Latino news media is produced, disseminated and consumed has varied considerably during these more than 200 years, but more extremely during these past two decades. Since the premier of Latino USA, on April 1993, as one of the first experiments to create an English-language Latino-centered public radio program in NPR to the Kickstarter crowdfunding campaign to launch Radio Ambulante, a podcast that tells Latin American stories in Spanish in 2011, only two decades have passed, but the storytelling in a digital format and the sourcing of content has evolved considerably. Both, the changes of the demographics and the news media industry have converged in a conjunction in which not only have Latinx audiences grown in their linguistic complexity, but news media practices have evolved in nature (Retis, 2019b).

The rapid changes of the Latinx news media production, distribution and consumption accompanied the practices of their specific audiences, but are also a reflection of the larger new media American landscape. The majority of adults in the United States now get their news online and are favoring mobile devices over desktops/laptops (Walker, 2019); the online space has become a host for the digital homes of both legacy and new “born on the web” news outlets; and advertising revenues across digital outlets, beyond news, are growing, with technology companies playing a large role in the flow of both content and revenue (Pew Research Center, 2019). While Latinos’ needs of information and self-representation have remained constant throughout the decades, the ways they consume their news have been changing. In recent years, and more specifically in the last two decades, technological and economic forces have transformed general news media. The fragmentation of ethnic media (Mayer, 2001)—which historically played a significant role in the development of immigrant communities—presents challenges and opportunities for bilingual news.

Researchers have addressed the need to understand the evolution of media moving away from the traditional perspectives to conduct the analysis beyond technological determinism, examine innovative media platforms to understand the types of journalism they produce, and construct an integrated view of the media ecosystem (García, Lopez & Vázquez, 2019; Scolari, 2013). Drawing on Scolari, the ecology metaphor to media can be interpreted in two complementary ways: 1) the media as environments or 2) the media as species that interact with each other (Scolari, 2012). He argues how both media history and media archeology have demonstrated that “all media were once new media” (Gitelman & Pingree, 2003, p. xi), repositioning the emergence of new forms of communication in a context that is much wider and less linked to the urgencies of the market and the marketing discourse. To overcome traditional approaches, researchers suggest to study new models of content production within the framework of diversity and the interdisciplinary nature of journalism studies (García, Lopez & Vázquez, 2019).

Following the discussion on the analysis of media evolutions, scholars have embarked on the task of defining the media that emerged as a result of the most recent technological transformation in news media and information consumption. Contrary to legacy media, these types of new media confluence in a myriad of disparate ventures. Lerman and Cohen-Avigdor (2004) incorporated the perspective of a natural life cycle of new media evolution in a six-phase model: 1) birth, 2) market penetration, 3) growth, 4) maturation, 5) defensive resistance, and 6) adaptation, convergence, or obsolescence. Scolari (2012) argues that to facilitate its application to different media and historical contexts, this natural life cycle model can be condensed into three phases: 1) emergence, 2) dominance, and 3) survival or extinction.

Bringing this perspective into the analysis of Latinx news media one can try to understand the socio-demographic changes, the evolution of the news media landscape, and the growth of both Latinx Spanish-language speakers and English-language speakers. This proposal is not a linear one that overviews the history of Latino media as a historical sequence of events, but a comprehensive understanding of intermediality seeking to provide elements of a complex environment in which Latinx media coexist and interact with mainstream media and other ethnic media. Moreover, this study seeks to understand how they intertwine at a local, regional, national, binational, transnational, and even translocal levels. As Scolari suggests (2012), the emergence, dominance, and survival or extinction phases and processes can overlap and it is essential to keep in mind the diversity of media and communication experiences at different moments of their simultaneous developments.

The Transnational and Translocal Nature of Latinx and Their Media

New technological platforms, social networks, and the immediacy of virtual communication point to transnational communications processes in which individual and collective identities reproduce complex historical, social, and cultural dynamics. In this regard, the academy needs to understand the impacts that the social dynamics of transnational groups have on their own members and on others, as they are proving to be a key element of globalization processes. Networks and migratory chain viewpoint permit us to comprehend the reconfiguration of these ties within transnationalism (Guarnizo & Smith, 1998; Levitt and Glick Schiller, 2004). The study of media flows and counterflows (Thussu 2007), the shape and evolution of media linguistic regions (Sinclair & Straubhaar, 2013), and the culture industries (Dávila, 2001; Yúdice, 2002), much like class media (Wilson, Gutierrez & Chao, 2003), enables us to understand the macrostructural complexities of media production, circulation, and consumption. More concretely, studies from diasporic transnationalism and media spaces (Georgiou, 2006) elucidate the particularities and contradictions of the communicative practices of Latinx communities and their news media habits.

Until recently, television was the main source of information for Latinx communities followed by Internet, radio, and print newspapers. A report published in 2018 showed an impressive shift, by demonstrating how on a typical weekday, three out of four Latinxs get their news online, nearly equal to the share who do so from television. This growth mirrors the trend in the overall U.S. population (Flores & Lopez, 2018). Behind this trend lie significant divides across generations, language use, and immigrant status among Latinos. As argued earlier, it is essential to understand the transformation of Latinx audiences and how their news media consumption practices influence the transformation of the media they check for their news. Latinx millennials are driving many of the recent changes in Latinxs’ news consumption. Moreover, this generation (those ages 18 to 35) has a higher share than among other racial or ethnic groups (Flores & Lopez, 2018). On the other hand, foreign-born Latinxs tend to be older than the U.S.-born Latinxs, and continue to rely on television for news. However, the complexity of Latinx groups also drive the need for immediate information at different geographical levels.

With the incursion of the internet but more specifically with the transition from web 1.0 to 2.0, a series of opportunities were opened to produce news media beyond the traditional outlets. Soon the concept of “new media” was embraced to differentiate digital publications from “legacy media” or those who remain in the traditional print or broadcast platforms. More recently, as Salaverría (2019) annotated, scholars have distinguished between “legacy” digital publications, meaning those derived from consolidated journalism brands, and new online publications, characterized by their digital nature and recent origins. As he listed, a variety of new labels have emerged in trying to categorize the recent ventures in the digital scenario, “such as ‘digital-born’ (Nicholls, Shabbir, & Nielsen, 2016), ‘digital-native’ (Pew Research Center, 2015; Wu, 2016), ‘online-native’ (Harlow & Salaverría, 2016), or even simply as ‘pure players’ (Sirkkunen & Cook, 2012) or ‘start-ups’ (Naldi & Picard, 2012; Wagemans, Witschge, & Deuze, 2016)” (as cited in Salaverría, 2020, p. 1). In his editorial for the issue “Digital News Media: Trends and Challenges,” Salaverría (2020) annotates that most research about digital-native news media phenomenon has been limited to case studies, exploring either global-reaching brands or some local cases. He argues that one of the main limitations of case studies is that they usually focus on the most successful and well-developed examples, the characteristics of which hardly apply to the average publications. In order to get a more nuanced idea about the contributions and problems of the average digital-native news media, broader studies are needed. This is precisely one of the main objectives of the larger research project in which this article is based on: to map and explore the challenges and opportunities that a myriad of new ventures is facing when offering news information for diverse Latinx audiences. Drawing on Wu (2016), for this article, the focus is on Latinx “digital-native media” to describe the ventures that were born and grown entirely online.

Mapping Digital-Native U.S. Latinx News Media

In the early 2010s, Franklin (2013) argued that digital journalism is complex, expansive and constitutes a massive and ill-defined communications terrain which is constantly in flux. It “engages different types of journalistic organizations and individuals, embraces distinctive content formats and styles, involves contributors with divergent editorial ambitions, professional backgrounds, and educational experiences and achievements, who strive to reach diverse audiences” (Franklin, 2013, p. 2). Almost a decade later, research has demonstrated that digital journalism not only has a great potential to improve journalism, but also represents a series of challenges due to the pressures facing new businesses among other specific risks (Buschow, 2020).

Embarking in the task of studying digital journalism has its own challenges and opportunities as it is a rapidly changing field that unfolds around us. In this context, Franklin and Eldridge (2018) suggest to think about this area of study and its place in our broader societies; take into consideration that digital developments have been more uneven than expected; and prevent leaving important debates and unforeseen consequences underexplored. Most recent investigations indicate that journalism studies scholars should consider the priority that has been placed on the way digital technologies have been integrated into journalism. They call for a renewed emphasis on the overall digital ecology, in which journalism is woven throughout a range of media and networks (Eldridge & Franklin, 2018).

Drawing on Husband’s notion of the multi-ethnic public sphere (1998), Yu proposes to include a multicultural media system that considers both availability and accessibility of ethnic media for a larger audience. By mapping ethnic media that produce in English or bilingually online, studies help advance theoretical debates on ethnic media as independent spheres focused on speaking by and listening to minority voices to move the perspective into understanding what needs to be in place in order to enable these voices to be heard (Yu, 2017).

The larger research project in which this study is based, seeks to bring light to an understudied area in the American digital journalism studies: how race, language, and news information needs intertwine in the American news media landscapes in their stages of emergence, dominance, and survival or extinction. In other words, looking at the Latinx component of the American digital journalism.

Since 2001, and more specifically between the mid-2000s and mid-2010s, the American news media landscape has witnessed the emergence of new spaces of production, distribution and consumption of news media with information about or relevant to Latinx communities. In the early stages, these types of media were launched in the midst of the advances of online communication technologies. After the economic recession and more precisely during the late 2000s and beginning of the 2010s, Latinx digital-born media advanced their engagement with Latinx communities in English and Spanish.

At the change of the new decade new synergies of survival or extinction took place in various and diverse platforms.

In this study, the aim is to examine and understand the current situation of Latinx digital-native media and explore their engagement with their audiences beyond language, race, age and ethnicity. This is done by exploring its transnational nature and understand how these types of media interact locally, nationally, and internationally. Consequently, our project seeks to answer the following research question:

RQ1: What is the current state of Latinx digital-native news media in the United States?

In order to do so, the researchers looked into who they are, where they are located, what platforms they are using, and what they interpret as their mission. It can be argued that digital-native Latinx news media are journalistic ventures launched, developed, and maintained online to gather, assess, present, and disseminate news and information about, or relevant to, Latinx communities. Produced in Spanish, English, or bilingually, they are of recent origin and characterized by their digital nature, tend to produce original content for more than one platform, and increasingly engage with their audiences through social media. Due to the ever-evolving contexts in the post-broadcast era and with the advent of social media, digital Latinx news production, dissemination, and consumption are transnational and bilingual. It goes beyond informing in two languages but understanding linguistic and cultural diversity as well as innovative ways of storytelling.

The transnational nature of Latinx communities demands a transnational perspective that puts Latinx groups at the center of the analysis and explores the fluidity of their news habits. Efforts in mapping these news media outlets using digital ethnography methods provides the opportunity to understand how they are created, launched, and developed.

Methodology

The objectives of this paper are two-fold: 1) to contribute with a first attempt to mapping the digital-native Latino news media in the United States and 2) to provide a preliminary categorization of new models of digital-native Latino journalism in an era of fragmentation.

To answer the research question and fulfill the objectives of the project, this study employed a mixed methodological approach. Digital ethnography methods were front and center to this study because of the nature of the news media organizations that are the focus of this research and because of the multiple digital platforms where they have a presence. In addition to that, qualitative and quantitative content analysis was used to collect descriptions of platforms, objectives and mission, and business models.

Digital ethnography research does not differ from ethnography in the sense that participant observation is still its core method (Boellstorff, 2012). The news organizations were considered the participants for this study but were not separated from the actual humans who give them life. The observation included, but was not limited to, the participants’ self-representation in the digital world, their digital journalistic products, their digital interactions with their audiences, and in some cases, the promotion or the extension of the news discourse by the journalists on their own digital spaces. In order to conduct the observation, the field site was defined as the network (Burrel, 2017) of all of the online sites where all the previously mentioned could be observed. Finally, the authors relied on their professional and academic experience following and observing Latino media in the United States for several years to “be able to put into words some aspect(s) of the field otherwise left unspoken” (Hine, 2017, p. 52).

In order to identify as many digital-native news organizations as possible, the authors performed an extensive search starting with projects such as The State of The Latino News Media (Mochkofsky & Maldonado, 2019), reports such as Hispanic Media Today (Retis, 2019), searched directories such as SembraMedia.com’s (n.d.), looked into crowdsourcing supporting organizations such as NewsMatch.org, paid close attention to suggestions offered by social media sites when visiting news organizations’ social media feeds, sought recommendations through personal networks, and conducted systematic web searches. The data collection and observations were conducted between March and October 2020.

The transnational nature of some projects presented challenges to identify digital-native Latinx news organizations. To limit the scope of this essay and to make it manageable, only journalistic projects totally or partially produced in the continental United States were included in this paper. News media produced in Puerto Rico and other Spanish speaking countries and territories were not included in this study, but they will be part of the larger project.

To identify if the journalism outlet was a digital-native, the authors analyzed the descriptions available in the sites’ “about us,” “mission,” and/or “vision” pages; consulted external sources, such as news reports about the launching of the outlet, and searched for indications of a life in the offline world. Several news organizations included in the study live only on social media or other online-only 44

platforms (i.e., messaging apps, podcast services), which automatically gave them the identity of a digital-native. The researchers encountered more than 120 news organizations that were not included in this paper because they were originally created based on a non-digital product. Many newspapers in Spanish fit in this category as well as recordings of sports news shows that are also distributed through podcasting services such as Apple Podcasts or Spotify. Two important cases not included in this study following this criterium are El Tecolote and Latino USA. In the former, the newspaper has now an important and renovated online presence, and in the latter, the show is not tied anymore to a radio station and produces more content than its original Sunday show. Nevertheless, they were not included in this contribution because they were not entirely born and grown online (Wu, 2016), but are part of the larger project in which this study is based on.

News media was defined as producing hard and soft current news (Boczkowski, 2009; Tuchman, 1973)—which included news reports, analysis, opinion, and commentary but not long form, crónica, or fact-checking. Journalism projects were defined as ongoing projects at the time of evaluation. Projects that consisted of a short and finite series of articles, podcasts, or videos were not included this time but are part of our extended study.

Drawing on Harlow and Salaverria’s (2016) categorization of digital natives in Latin America, this study adopted the following: 1) ownership: private, public, or nonprofit; 2) philosophy or their approach to the production of news: commercial, nonprofit, or educational; 3) technological approach to news: traditional, or innovative. In addition to their classification, the researchers looked at: 4) platform: which included website, podcast, social media, messaging app, or multiple if the news organization produced original content on multiple platforms and not simply distributed the same content on different platforms; 5) geographical location: state; 6) size: one-person-band (1 to 4 people involved), micro (5-15), small (16-50), medium (51-200), or large (201-plus); 7) audience: hyperlocal, local, regional, national, and transnational; and 8) language: Spanish, English, Spanglish, or bilingual.

Findings

RQ1: What is the current state of Latinx digital-native news media in the United States?

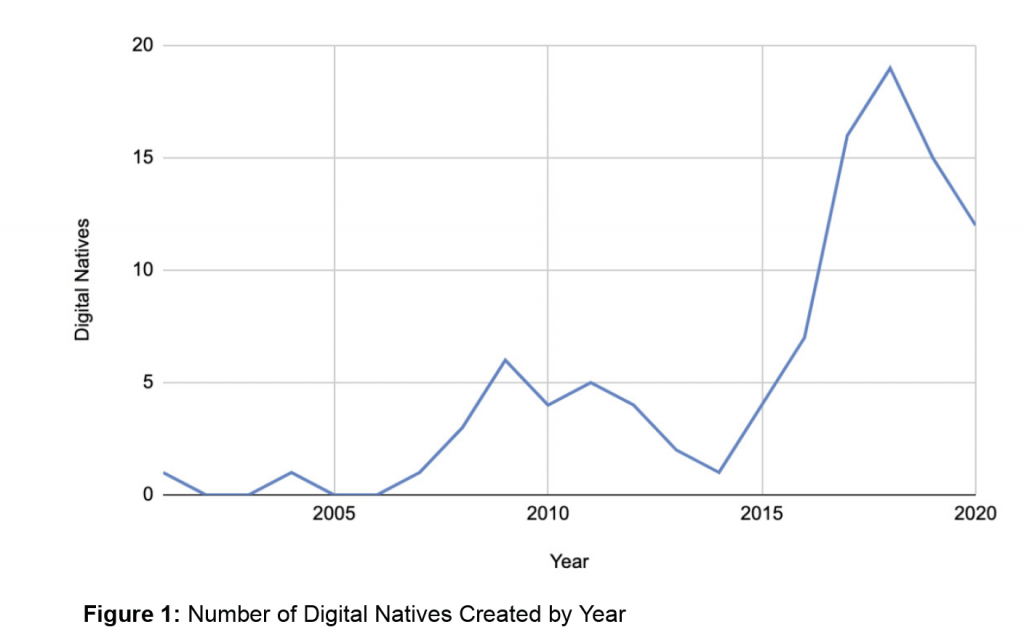

The analysis yielded 103 digital-native Latino news media projects. The oldest was founded in 2001 (¡LatinoLA!) and the most recent in 2020. The year 2018 was the top one with 19 digital natives initiating operations that year followed by 2017 and 2019 with 16 and 15 new digital natives each year respectively. In other words, although Latinx digital natives have been around for a long time, 62 news organizations (61%) are 4 years old or younger. (See Figure 1.)

More than half of the organizations (54.4%) delivered their content only in Spanish, 28% only in English, and 15.5% were bilingual delivering news in both English and Spanish. The podcast ¿Qué Pasa Midwest? was the only organization that delivered their news in a fully bilingual format because the host switched languages to make the content understandable in both languages. The news and satire site, Pocho, was the only one that delivered them consistently in English and Spanglish.

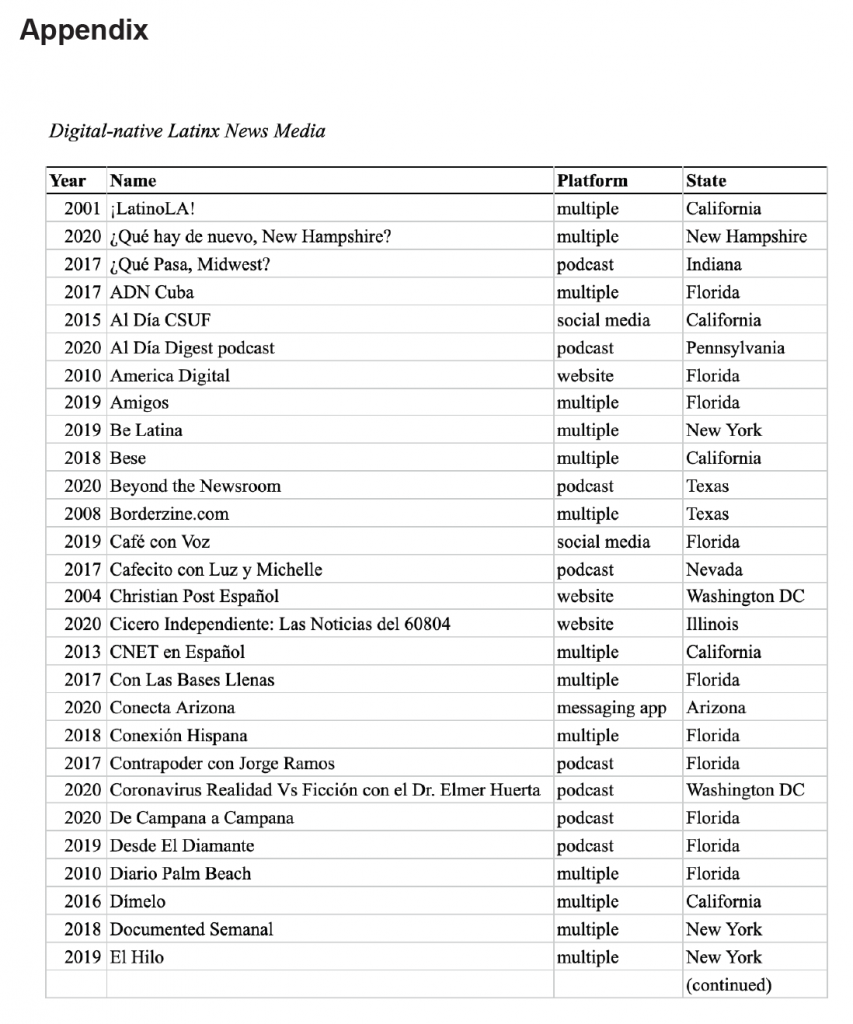

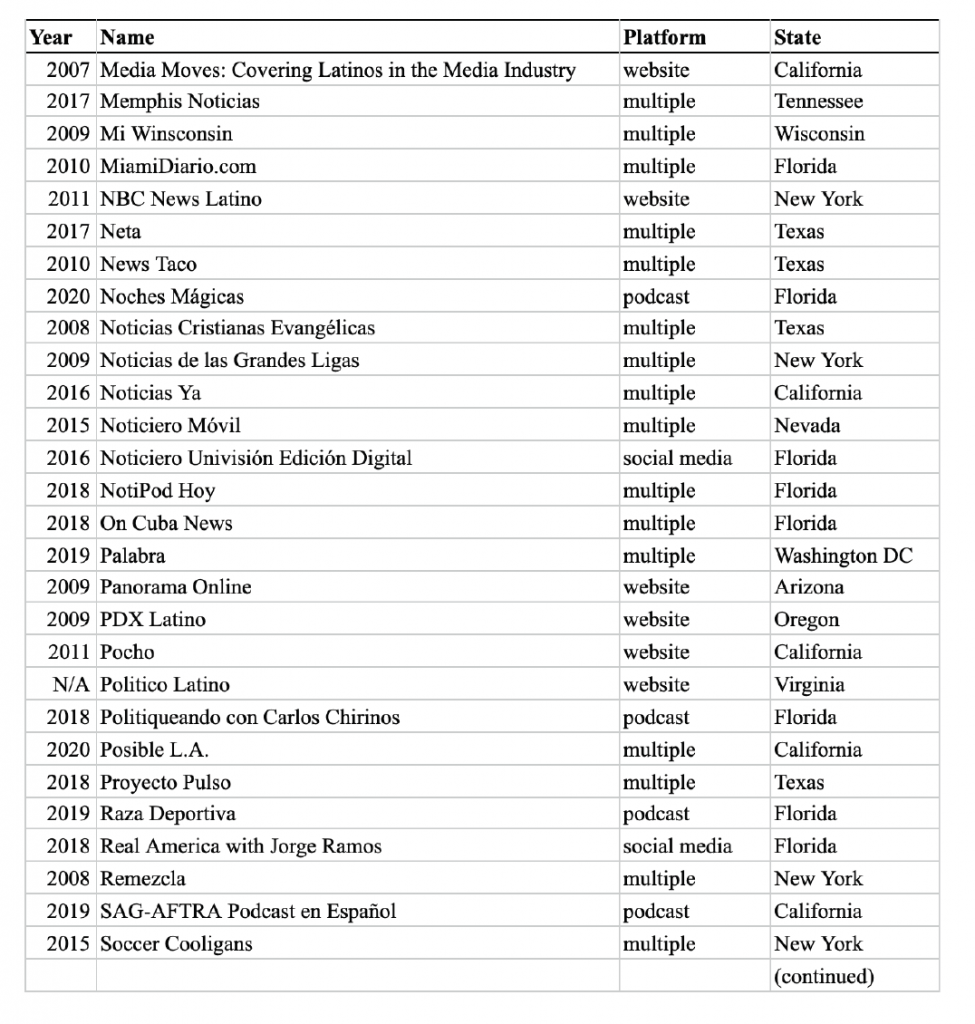

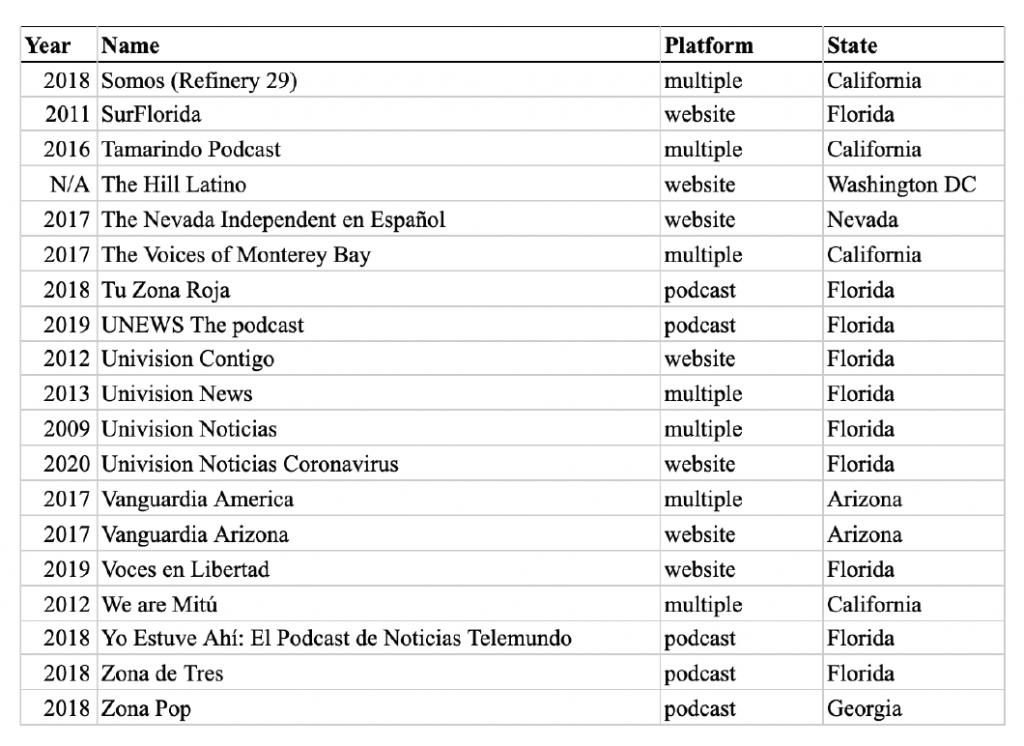

Four states concentrated 73.8% of the Latinx news organizations: Florida (34%), California (19.4%), New York (12.6%), and Texas (7.8%) with organizations having a presence in 20 out of the 50 states in the United States. (See Appendix).

A great majority (76.7%) of these organizations were identified as privately funded, 21.4% were nonprofit, and only 2 (1.9%) organizations were funded through public media (local public radio and television stations under the Corporation of Public Broadcasting). Among the digital-natives categorized as nonprofit, six (5.8%) were identified as educational because their parent organizations are universities.

Regarding their size, the majority of digital natives (77.7%) have 15 or less people in their staff. Almost half of those (40%) were organizations that were run by four or less people and that have been classified as one-person-band. The 46

other half, 37.7%, were organizations with a staff between five and 15 people (micro). For the remaining organizations, 1.9% were small (16-50 employees), 7.8% were medium (21-200), 7.8% were large (201-plus), and 4.8% were identified as automated services such as sections for Latinos on NBC, Politico, The Hill, among others.

Finally, about a quarter (27%) of the digital natives were backed by or part of traditional media conglomerates such as Univision, Telemundo, ESPN, NBC, The Washington Post, or The McClatchy Company. In other words, the large minority of digital efforts (73%) are being supported by independent and not-for-profit efforts unlike traditional Latino news media, which is dominated by conglomerates, such as Univision, Telemundo, and Impremedia.

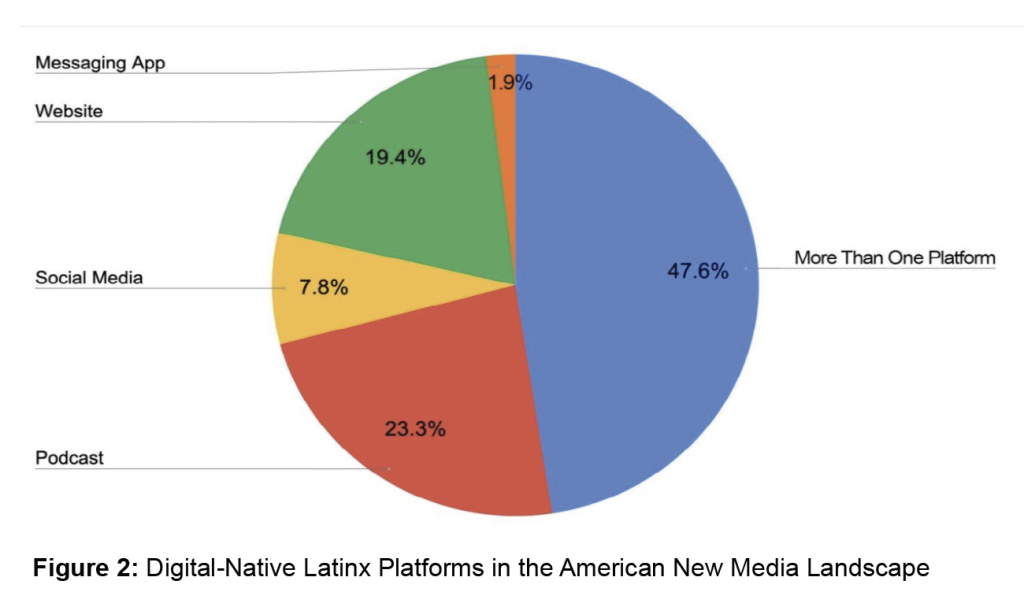

Digital-Native Latinx Platforms in the American New Media Landscape

Almost half of the Latinx digital-native outlets analyzed during March and October 2020 (47.6%) produced original content for more than one platform followed by 23.3% that produced only podcasts, 19.4% only content for websites, 7.8% only content for social media, and 1.9% only for messaging apps. Overall, the most popular platform was website (57.1%) followed by podcast (46.7%), social media (41.9%) and messaging app (7.6%). (See Figure 2.)

Regarding audience reach and engagement of Latinx digital native news outlets, our study found that the messaging app WhatsApp is emerging as a new platform to deliver news for Spanish-speaking Latinx communities. Six out of the eight organizations who used messaging apps to deliver news, used WhatsApp as a platform. Two of them used it as the most important platform to deliver the news (Conecta Arizona and ¿Qué Hay de Nuevo New Hampshire?). Facebook (78.6%) and Twitter (75.7%) were the most popular social media networks where the digital natives had a presence followed by Instagram (60.2%) and Other (24.3%) such as LinkedIn, Periscope, and Snapchat.

The news content produced by the news organizations on their different platforms was reviewed to understand the ways they employed the digitalness or the multimedia, interaction, or participatory affordances of the different platforms (Harlow & Salaverría, 2016). Organizations who produced content following traditional means (i.e., written text, photography, audio or video newscasts) were labeled as traditional while organizations who took advantage of the affordances of different platforms, especially social media (i.e., Facebook Live, Facebook Watch, IGTV) were labeled innovative. More than half (59.2%) of the digital natives were identified as innovative and the remaining 40.8% were identified as traditional. This finding suggests that the new generations of digitally savvy journalists and their interest to serve larger and more diverse Latinx communities—as it will be shown in the next section—are driving the exploitation of the affordances of the new digital platforms.

Latinx Diasporic Transnational Media Spaces

The study of Latin American diasporas and their media requires an interdisciplinary perspective that helps understand hegemonic and subaltern dynamics around capital/population/media flows (Retis, 2019a). During the months of March and October of 2020, the observations to the Latinx digital-native news organizations’ presence in the digital world as well as the content they produced allowed the identification of their approaches to the production of news in terms of the audiences they wanted to reach as well as represent. Following these criteria, the analysis shows that half of the news organizations (50.5%) were oriented toward a Latinx national audience, followed by transnational (18.4%), regional (15.5%), hyperlocal (5.8%), and local (9.7%).

Most news organizations who defined their audiences as hyperlocal, local, or regional would clearly establish that in their self-descriptions. For instance, Cicero Independiente, a website with news from Cicero, Illinois, had a subhead that read: “Bringing you news from the 60804” (Cicero Independiente, n.d.) clearly referencing Cicero’s zip code; the news site MiamiDiario.com described itself as the window to Miami and encouraged its readers to “enjoy Miami in Spanish with them” (author’s translation) (MiamiDiario.com, n.d.); and The Nevada Independent en Español described itself as having reporters covering the north and south of Nevada (Gray, 2020). Organizations who sought to reach audiences at the national level would describe their mission as to report about issues that concerned all Latinos. For instance, Latin Post declared to be an “online media company that aims to serve the Latino population in the United States” (Latin Post, n.d.) and Real America with Jorge Ramos described the outlet as an “exploration of America” (Real America with Jorge Ramos, n.d.).

Preliminary findings of the ongoing research project indicate that the Latinx digital-native media outlets that reached and represented transnational audiences had some or all of the following characteristics:

1) Part of their staff was located outside the United States—or moved back and forth—but reported on issues inside the United States. Some examples are El Washington Post, a podcast in Spanish with a Spanish host located in Washington D.C., a Colombian host in Madrid, Spain, and a Colombian host in Bogota, Colombia. They report on world issues as well as the most important events going on in the United States for Spanish-speaking audiences in the United States and the world. A similar example is the podcast El Hilo, that covers issues in the Americas with Latin American hosts in London and Mexico City but produced and edited from New York City.

2) Part of their staff literally inhabits the U.S.-Mexico border and reports and interacts with audiences on both sides of the border. Borderzine.com, created in 2008, is the oldest digital native doing this at El Paso-Ciudad Juárez border. Part of its staff are Mexican students who attend The University of Texas at El Paso but live in Ciudad Juárez and cross the border every day. El Migrante, a project by Internews’ Listening Post Collective, has journalists in the San Diego-Tijuana and El Paso-Ciudad Juárez borders reporting on stories and resources for and about immigrants on the border. They distribute a digital newsletter through WhatsApp and produce a weekly podcast for their audience with literacy problems. Finally, Conecta Arizona reproduces a radio newscast, delivers news, and discusses salient issues all on WhatsApp with its audiences in Arizona and Sonora, Mexico.

3) Their staff are refugees from another country who report for the same group in the United States and other parts of the world. Two news organizations reflect this group very clearly, Voces en Libertad and Café con Voz which are organizations created by Nicaraguan journalists who had to leave their country because of persecution by the Ortega administration. In the case of Voces en Libertad, the journalists report from Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Spain, and the United States about what is happening in Nicaragua with the intention to inform the Nicaraguan community in the United States and Café con Voz is produced from Miami with a similar objective.

During the observation, a diverse set of editorial perspectives were identified within these outlets. More in-depth examination of their contents and how they can become influential for their audiences will be developed in the larger research project this study is based on. What we can indicate here is the trend in seeking to amplify the Latinx voices in the United States.

Informing, Amplifying, and Elevating the U.S. Latinx Voices

The objectives and mission presented by the digital-native Latinx news media varied but three strong themes emerged from their self-descriptions of their objectives and mission. More than 15% of the organizations defined their mission as to inform their audiences of the issues that impact them. Most of the digital natives in this group delivered their news only in Spanish catering to Latinx born outside the United States and/or recently arrived to the United States. For instance, the audio newscast delivered via WhatsApp, ¿Qué Hay de Nuevo, New Hampshire?, described itself as:

A new radio newscast produced by New Hampshire Public Radio.

Receive a five-minute audio file from Monday to Friday with the most important stories of the day and with up-to-date information about how the Coronavirus pandemic is affecting the economy, politics, society, and New Hampshire’s cultural context. (Author’s translation) (Nhpr.org, n.d.)

A second group, of about a fifth of the outlets, sought to write or deliver stories about Latinos or through Latino lenses in order to amplify the voices or the presence of the Latinx communities in the United States. These news organizations would talk about how Latinx communities have been under reported or ignored and they saw the need to correct that wrong. For instance, El Tímpano described its mission as:

El Tímpano—Spanish for “eardrum”—informs, engages, and amplifies the voices of Oakland’s Latino immigrants. Through innovative approaches to local journalism and civic engagement, El Tímpano surfaces community members’ stories, questions, and concerns on local and national issues, and provides information relevant to their needs. (El Tímpano, n.d.)

Finally, a third group, smaller in numbers but with a stronger message, also talked about amplifying the presence of Latinx communities in the United States. However, this group used the word “elevating” signaling to an elevation of the status of and the discourse about Latinos. These news organizations would talk about correcting stereotyping and false and inaccurate media narratives. For instance, NBC Latino talked about “elevating the conversation around Latinos” (NBC Latino, n.d.) and Somos from Refinery29, sought “to elevate, educate, and inspire a new generation of changemakers committed to Latinx visibility” (Refinery29, n.d.) 50

Discussion

This study consisted of digital ethnographic observations of 103 digital-native Latinx news media in the continental United States. Our findings confirmed some historical trends. First, that Latinx media tends to concentrate in the South and Southwest; and second, that the prevailing ownership model for most Latino outlets is private ownership and it is conducted often as an independent effort (Mochkofsky & Maldonado, 2019; Retis, 2019b). However, the findings also show that digital-natives are springing up in Northern states as well where Latinx presence is growing such as the Midwest (i.e., Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Wisconsin, etc.) (Noe-Bustamante et al., 2020) and that there is an increasing number of news outlets funded through philanthropic efforts and/or local crowdfunding. In addition to that, it is important to highlight the presence of student media and journalism schools’ efforts involved in the production of news for Latinx audiences. Historically, campus-based newspapers have played an important role in advocating for Latinx communities (Simón Salazar, 2019) and these findings suggest that the new generation of Latinx student journalists, professionals, and professors are continuing that work.

Latinx digital-natives are consistently producing original content for more than one platform and social media is increasingly part of that effort. This trend mirrors what is happening in the general landscape: the majority of adults in the United States get at least some news online; and the online space has become a host for the digital homes of both legacy news outlets and new “born on the web” news outlets. This also reflects the fact that not only Latinx audiences are moving into multiple online and social media options, but the general landscape is evolving in this direction. As digital advertising revenue across all digital entities continues to grow, digital technology companies are playing a large role in the flow of news and revenue (Pew Research Center, 2019).

The media spaces created by Latinx digital-native news organizations are increasingly becoming transnational. Close to 20% of the observed news organizations had staff outside the United States who reported about issues in the country, had reporters not only covering but inhabiting both sides of the U.S.- Mexico border, or were refugees who reported about their countries of origin. Drawing on Georgiou (2006), we found that Latinx diasporic transnationalism became less about the place and more about the space; thus, these complex and multifaceted geographical synergies instead of excluding each other, intertwine at various levels where we can identify the emergence and development of consensual and contradictory forms of transnational imagined communities (Anderson, 2006.)

Last but not least, Latinx news organizations continue to show a strong interest in informing, as well as amplifying the Latinx community’s voices and elevating the discussion about their communities which reveals the important role these organizations play in the U. S. multicultural media system focused on enabling Latinx voices to be heard (Yu, 2017).

Conclusions

This contribution attempted to examine and understand the complex nature of digital-native Latinx news media outlets being produced in various regions in the United States. We sought to advance the scope of our study beyond geographical boundaries due to the diasporic transnational nature of these ventures. Even though this contribution presents the preliminary findings of a larger research project, it demonstrates main trends occurring within the U.S. Latinx digital information circuits.

Our observations during 2020, helped to identify that even though Latinx digital-native outlets have been present very early in the digital age, most of them are very young and therefore are under researched. The fast pace of the technological evolution and the business challenges will probably mean challenges for researchers as well; however, it is important to continually map and monitor these changes as they are part of the larger United States multicultural media landscape.

Spanish continues to be the dominant language used for Latinx news media; however, following the language preferences of the different generations of Latinx communities, offerings of news in English are increasingly growing as it was reflected in the number of English-only outlets reviewed in this study and also in the bilingual offerings amounting to close to half of the total.

The digital environment and, more specifically, these digital-natives are boosting the development of Latinx diasporic transnational media spaces. Latinx digital-natives not only are created where Latinx communities have historically resided (South and Southwest) or where Latinx communities are newly migrating (Midwest), they are also facilitating spaces for diasporic transnationalism where news organizations, established in and publishing from the United States, have personnel all over the world that reports for Latinx communities in the United States.

Latinx media continues to be a mostly independent effort where the majority of outlets have less than 15 people and are not backed by the traditional media conglomerates, but with evidence of a growing philanthropic funding either by foundations or crowdfunding.52

As the general news media consumers, Latinx audiences are moving into multiple online and social media options. As digital advertising revenue across all digital entities continues to grow, digital technology companies are playing a large role in the flow of news and revenue. Future research will examine these types of synergies within digital native Latinx news media outlets.

This study shows that, more than ever, contemporary digital-native Latinx news media participate in the heightened interconnectivity and intermediality practices beyond geographical boundaries, language barriers, and hyper-fragmentation of audiences (Deuze & Witschge, 2020; Elleström, 2010; Jenkins, 2006; Jenkins & Deuze, 2008). The complexity of their nature becomes fluid and travels back and forth from the local to the regional and foremost to the international level and drives back to hyperlocal, local, and even translocal levels. Mapping all these synergies demands a comprehensive understanding of multiple variables that intervene in these simultaneous news media production and consumption activities. Although a necessary effort, this study shows only the tip of the iceberg. This study did not include input from the news media producers and therefore it reflects only what it is in the surface. More research is needed to learn about the routines that create these transnational spaces and the innovation that these challenges generate.

Many Latinxs speak English and Spanish. This bilingualism is reflected in their news habits. Hispanic millennials use English-language news sources more than older generations. Foreign-born Latinos prefer Spanish-language news sources. These trends in news habits have influenced Latinx news media shifts. The lack of studies on bilingual digital media is, paradoxically, inversely proportional to the emergence of new educational projects to teach bilingual journalism. This is one of the main reasons we have embarked on this collaborative mapping project through a digital ethnography lens. The ongoing larger project seeks to analyze and understand the industry, strategies, new business models, and interactions with audiences. The results of this study will help to assess, design, and update the pedagogical curricula of several bilingual journalism programs in the Southwest.

This study presents the current situation of the Latinx digital-native news media in the United States. Closely following historical and new trends among these outlets can provide educators with sorely needed information to train bilingual journalists who can better serve their Latinx communities by understanding their information needs and creating the transnational spaces they demand. 53

References

Aguilera, J. (2020). Why it’s a mistake to simplify the ‘Latino Vote.’ Time, November 5, 2020. Retrieved from https://time.com/5907525/latino-vote- 2020-election/

Anderson, B. (2006). Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. Verso.

Associated Press (AP). (2019, May 21). Univision set to finish as No. 1 Spanish-language network in primetime for 27th consecutive broadcast season; Ranks among ABC, CBS, FOX and NBC as top five broadcast network. Retrieved from https://apnews.com/press-release/pr-businesswire/2faf760b6e0b4705a1e03d86 1d9c7475

Benkler, Y. (2006). The wealth of networks: How social production transforms markets and freedom. Yale University Press.

Bimbauer, B. (2018). The rise of nonprofit investigative journalism in the United States. Routledge.

Boczkowski, P. J. (2009). Rethinking hard and soft news production: From common ground to divergent paths. Journal of Communication, 59(1), 98–116. DOI:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2008.01406.x

Boellstorff, T. (2012). Rethinking digital anthropology. In H. A. Horst & D. Miller (Eds.), Digital anthropology, (pp. 39-60). Routledge. https://doi. org/10.4324/9781003085201

Burrell, J. (2017). The Fieldsite as a network: A strategy for locating ethnographic research. In L. Hjorth, H. Horst, A. Galloway, & G. Bell (Eds.), The Routledge companion to digital ethnography, (pp. 77–86). Routledge.

Chinula, M. (2017, June 19). 7 business models that could save the future of journalism. Media Entrepreneurship. Retrieved from https://ijnet.org/en/story/7- business-models-could-save-future-journalism

Cicero Independiente. (n.d.) Home. Retrieved November 9, 2020 from https:// www.ciceroindependiente.com/categories-english 54

Cramer F. (2015). What is “post-digital”? In D. M. Berry, & M. Dieter (Eds.), Postdigital aesthetics: Art, computation and design, (pp. 14–26). Palgrave Macmillan.

Dávila, A. (2001). Latinos, Inc.: The marketing and making of a people. University of California Press.

Deuze, M., & Witschge, T. (2020). Beyond Journalism. Polity Press.

El Tímpano. (n.d.) Home. Retrieved November 9, 2020, from https://www.eltimpano.org/

Eldridge II, S., Hess, K., Tandoc Jr., E. C., & Westlund, O. (2019). Navigating the scholarly terrain: Introducing the digital journalism studies compass. Digital Journalism, 7(3), 386–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2019.1599724

Eldridge II, S., & Franklin, B. (2018). Introducing the complexities of developments in digital journalism studies. In S. Eldridge, & B. Franklin (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of developments in digital journalism studies (1 ed.). Routledge.

Elleström, L. (Ed.) (2010). Media borders, multimodality and intermediality. Palgrave.

Ferruchi, P., & Alaimo, K. (2019). Escaping the news desert: Nonprofit news and open-system journalism organizations. Journalism, 21(4), 489–506. https://doi. org/10.1177/1464884919886437

Flores, A., & Lopez, H. (2018). Among U.S. Latinos, the internet now rivals television as source for news. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https:// www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/01/11/among-u-s-latinos-the-internet-now-rivals-television-as-a-source-for-news/

Franklin, B. (2014). The future of journalism in an age of digital media and economic uncertainty. Journalism Studies, 15(5), 481–499. DOI:10.1080/14616 70X.2014.930254

Franklin, B. (2013). Editorial. Digital Journalism, 1(1), 1–5, DOI:10.1080/216708 11.2012.740264

García, B., López, X., & Vázquez, J. (2019). Journalism in digital native media: Beyond technological determinism. Media and Communication, 8(2), 5–15.55

Georgiou, M. (2006). Diaspora, identity and the media: Diasporic transnationalism and mediated spatialities. Hampton Press.

Gitelman, L., & Pingree, G. (Eds.). (2003). New media, 1740–1915. The MIT Press.

Gray, L. (Host). (2020, November 2). Cafecito con Luz y Michelle Episodio 143: Un vistazo a la boleta electoral de Nevada [Audio podcast]. https://thenevadaindependent.com/podcast/cafecito-con-luz-y-michelle-episodio-143-un-vistazo-a-la-boleta-electoral-de-nevada

Guarnizo, L., & Smith, M. (1998). Transnationalism from below. Transaction Publishers.

Harlow, S., & Salaverría, R. (2016) Regenerating journalism. Digital Journalism, 4(8), 1001–1019. DOI:10.1080/21670811.2015.1135752

Hine, C. (2017). From virtual ethnography to the embedded, embodied, everyday internet. In L. Hjorth, H. Horst, A. Galloway, & G. Bell (Eds.), The Routledge companion to digital ethnography (pp. 47–54). Routledge.

Hurcombe, E., Burgess, J., & Harrington, S. (2019). What’s newsworthy about ‘social news’? Characteristics and potential of an emerging genre. Journalism, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1464884918793933

Husband, C. (1996). The right to be understood: Conceiving the multi-ethnic public sphere. Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research, 9(2): 205–215.

Husband, C. (1998). Differentiated citizenship and the multi-ethnic public sphere. Journal of International Communication, 5(1-2): 134–148.

Jian, L., & Usher, N. (2014). Crow-funded journalism. Journal of Computer- Mediated Communication, 19, 155–170.

Kaye, J., & Quinn, S. (2010). Funding journalism in the Digital Age: Business models, strategies, issues and trends. Peter Lang.

Jenkins, H. (2006) Convergence culture: Where old and new media collide. New York University Press.56

Jenkins, H., & Deuze, M. (2008). Editorial: Convergence culture. The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 14(1), 5–12.

Latin Post. (n.d.) About Us. Retrieved November 9, 2020 from https://www. latinpost.com/about-us

Lehman-Wilzig, S., & Cohen-Avigdor, N. (2004). The natural life cycle of new media evolution: Intermedia struggle for survival in the Internet age. New Media & Society, 6, 707–730. DOI:10.1177/146144804042524

Lenhoff, A., & Schudson, M. (2012). The classroom as newsroom: Leveraging university resources for public affairs reporting. International Journal of Communication, 6, 2677–2697.

Levitt, P., & Glick-Schiller, N. (2004). Conceptualizing simultaneity: A transnational social field perspective on society. International Migration Review, 38(145), 595–629.

Lewis, C. (2008). Seeking new ways to nurture the capacity to report. Without an independent news media, there is no credibility informed citizenry. Nieman Reports, Spring, 23–27.

Mayer, V. (2001). From segmented to fragmented: Latino media in San Antonio, Texas. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 78(2), 291–306.

MiamiDiario.com [@miami_diario] (n.d.). Tweets [Twitter Profile]. Retrieved November 9, 2020 from https://twitter.com/miami_diario

Mitchelstein, E., & Boczkowski, P. J. (2009). Between tradition and change: A review of recent research on online news production. Journalism, 10(5), 562– 586. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884909106533

Mochkofsky, G., & Maldonado, C. (2019). The state of the Latino news media. Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism. Retrieved from http://thelatinomediareport.journalism.cuny.edu/

Morton, T. (2012). This wheel’s on fire: New models for investigative journalism. Pacific Journalism Review, 18(1), 13–16.

NBC Latino. (n.d.) In Facebook [Facebook Page]. Retrieved November 9, 2020, from https://www.facebook.com/NBCLatino57

Nhpr.org (n.d.) Noticias en espanol. Retrieved November 9, 2020, from https:// www.nhpr.org/topic/noticias-en-espanol#stream/0

Noe-Bustamante, L., Lopez, M. H., & Krogstad, J. M. (2020) U.S. Hispanic population surpassed 60 million in 2019, but growth has slowed. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/07/07/u-s-hispanic-population-surpassed-60-million-in-2019-but-growth-has-slowed/

Pew Research Center (2019). The state of news media. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/topics/state-of-the-news-media/

Rakich, N., & Thomson-Deveaux, A. (2020, September 22). There’s no such thing as the “Latino vote”. FiveThirtyEight. Retrieved from https://fivethirtyeight. com/features/theres-no-such-thing-as-the-latino-vote/

Real America with Jorge Ramos. (n.d.) In Facebook [Facebook Page]. Retrieved November 9, 2020 from https://www.facebook.com/RealAmericaWithJorgeRamos/about

Requejo-Alemán, J., & Lugo-Ocando, J. (2014). Assessing the sustainability of Latin American investigative non-profit journalism. Journalism Studies, 15(5), 522–532. DOI: 10.1080/1461670X.2014.885269

Refinery29. (n.d.) Somos. Retrieved November 9, 2020, from https://www.refinery29.com/en-us/latinx-somos

Retis, J. (2019a). Homogenizing heterogeneity in transnational contexts: Contemporary Latin American diasporas and the media in the Global North. In J. Retis & R. Tsagarousianou (Eds.), The handbook of diasporas, media, and culture (pp. 115–136). Willey-Blackwell.

Retis, J. (2019b). Hispanic media today. Democracy Fund. Retrieved from https://democracyfund.org/idea/hispanic-media-today/

Retis, J. (Forthcoming). Latino news media. In G. Borchard (Ed.), Encyclopedia of American journalism. 2nd edition. Sage.

Robinson, S. (2017). Teaching journalism for a better community: A Deweyan approach. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 94(1), 303–317. DOI: 10.1177/107769901668198658

Rosenthal, R. (2012). A multiplatform approach to investigative journalism, Pacific Journalism Review, 18(1), 17–29.

Salaverría, R. (2020). Exploring digital native news media. Media and Communication, 8(2), 1–4. DOI: 10.17645/mac.v8i2.3044

Salaverría, R. (2019). Digital journalism: 25 years of research. El Profesional de la Información, 28(1), 1–27. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2019.ene.01

Sembramedia.org. (n.d.) El ecosistema. Retrieved from https://directorio.sembramedia.org/el-ecosistema/

Scolari, C. (2013). Media evolution: Emergence, dominance, survival, and extinction in media ecology. International Journal of Communication 7, 1418– 1441.

Scolari, C. (2012). Media ecology: Exploring the metaphor to expand the theory. Communication Theory, 22(2), 204–225. DOI: 10.1111/j.1468- 2885.2012.01404.x

Simón Salazar, H. L. (2019). Movimiento voices on campus: The newspapers of the Chicano/a student movement. Journal of Alternative and Community Media, 4(3), 56–70.

Sinclair, J., & Straubhaar, J. (2013). Latin American television industries. Palgrave.

Thussu, D. (2007). Media on the move: Global flow and contra-flow. Routledge.

Tsagarousianou, R., & Retis, J. (2019). Diasporas, media, and culture: Exploring dimensions of human mobility and connectivity in the era of global interdependency. In J. Retis & R. Tsagarousianou (Eds.), The handbook of diaspora, media and culture (pp. 1–20). Willey-Blackwell.

Tuchman, G. (1973). Making news by doing work: Routinizing the unexpected. American Journal of Sociology, 79(1), 110–131.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2020, August 11). Profile America facts for features: CB20-FF.07. Hispanic Heritage Month 2020.59

Walker, M. (2019). Americans favor mobile devices over desktops and laptops for getting news. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/11/19/americans-favor-mobile-devices-over-desktops-and-laptops-for-getting-news/

Wilson, C., Gutierrez, F., & Chao, L. (2003). Racism, sexism, and the media: The rise of class communication in multicultural America. Sage.

Wu, L. (2016). Did you get the buzz? Are digital native media becoming mainstream? #ISOJ 6(1). Retrieved from https://isojjournal.wordpress. com/2016/04/14/did-you-get-the-buzz-are-digital-native-media-becoming-mainstream/

Yu, S. (2017). Multi-ethnic public sphere and accessible ethnic media: Mapping online English-language ethnic media. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44(11), 1976–1993.

Yúdice, G. (2002). Las industrias culturales: Más allá de la lógica puramente económica, el aporte social. Pensar Iberoamérica, June-September (1), 16–23.

Jessica Retis is Associate Professor in the School of Journalism and Director of the Master’s in Bilingual Journalism at the University of Arizona. Retis holds a Major in Communications (University of Lima), a Master’s in Latin American Studies (National Autonomous University of Mexico) and a Ph.D. in Contemporary Latin America (Complutense University of Madrid). She has two decades of journalism experience in Peru, Mexico, and Spain and has worked as a college educator for almost three decades in universities in the United States, Spain, and Mexico. Research areas include Latin America, international migration, diasporas and transnational communities; cultural industries; Latino media in Europe, North America and Asia; journalism studies, bilingual journalism, and journalism education.

Lourdes M. Cueva Chacón is Assistant Professor in the School of Journalism & Media Studies at San Diego State University. Cueva Chacón holds a M.S. in Information Science (UNC Chapel Hill), a M.A. in Communication (University of Texas El Paso), and a Ph.D. in Journalism (University of Texas Austin). Cueva Chacón has more than seven years of experience reporting the U.S.-Mexico border as well as Latinx communities in the United States. Her research areas include media sociology, coverage of minoritized and marginalized communities in the United States, digital-native news media in the Americas, and collaborative journalism in Latin America.