#MarchForOurLives: Tweeted teen voices in online news

By Kirsi Cheas, Noora Juvonen and Maiju Kannisto

[Citation: Cheas, K., Juvonen, N., & Kannisto, M. (2020). #MarchForOurLives: Tweeted teen voices in online news. #ISOJ Journal, 10(1), 61-83.]

In February 2018, a school shooting in Parkland, Florida led to a new student movement advocating for stricter gun laws. This article examines whether and how Generation Parkland has transformed public discussion on gun violence through Twitter activism. This article argues that in most media, the social media activism of Generation Parkland was taken seriously. However, the ideological biases of the news media have continued to affect coverage and play a role in the framing process, and there are still generational power hierarchies that shape the mediated voice of Generation Parkland.

A growing number of teenagers are questioning the ability of politics to change things, and they are increasingly willing to use their voices to enact social change. Young people have often been at the forefront of social movements, but in 2018 they dominated social media conversations and news coverage, forcing politicians to respond (e.g., Pimentel, 2018). Social media was their most potent organizing tool and a way for them to get their angry voices heard. However, the coverage of their tweeted voices in online news has been entangled in multiple power hierarchies between consumers and professional journalists, citizens and politics, and different generations and ideological orientations.

In February 2018, a mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, led to a new student movement—March For Our Lives—advocating for stricter gun laws. This article examines how Generation Parkland has reframed public discussion on gun violence through Twitter activism. On the one hand, this article analyzes the ways in which the use of tweets in online news has challenged the existing power hierarchies; on the other, it examines how journalistic practices and ideologies at the same time shape the sourcing and framing of news on youth activism. More specifically, the research questions of this article are: 1) How did Parkland youth use social media to get their voices heard? 2) How did the tweeted teen voices become subject to ideological divisions shaping the coverage in different online news media? 3) How were intergenerational power hierarchies negotiated in the coverage of Generation Parkland?

The concept of generation is used in this article because it has important implications for the activism of the Parkland students, including their experiences and skills and attitudes, especially in the use of social media. The researchers use Generation Parkland as an analytical concept even though Parkland youth don’t call themselves this.

A social generation paradigm has gained increasing currency as a method in analyzing young people’s relationship with the life course (e.g., Wyn & Woodman, 2006). Even though there is also considerable criticism of generational research (e.g., Burnett, 2003; France & Roberts, 2014), the researchers found the concept of generation useful in capturing the combination of experiences, skills and attitudes that identify the driving forces behind the Parkland activism. The concept of Generation Parkland provides a means to define Parkland activists by their place in the life cycle and by their membership in a cohort of individuals born at a similar time. This concept locates Parkland youth within specific sets of technical, social, cultural and political conditions (Wyn & Woodman, 2006). Generation is commensurate to the different socialization experiences of individuals; generations exist as specific collective identities (France & Roberts, 2014). According to the Pew Research Center, anyone born from 1997 onward is part of Generation Z (Dimock, 2019, para. 5). What is unique for Generation Z is that social media, constant connectivity, and on-demand entertainment are largely assumed (Dimock, 2019). These new generational categories, like the Generation Z, describe the relationship between young people, the Internet, and politics (Bessant, 2014, p. 6).

According to Seemiller and Grace (2019), members of Generation Z see violence all around them. Whether online, in their schools, or in their communities, many have a sense of fear and anxiety for their own safety and the safety of others (Seemiller & Grace, 2019, p. 30). Theoretical development of Generation Z is still a work in progress, and it has limitations such as recognizing the influence of power, especially in different social contexts. However, the anxiety and exposure to incessant violence associated with the Generation Z does capture the experience that is central to Generation Parkland. Even to such an extent that many of the Parkland students have identified themselves as part of a “mass-shooting generation,” referring to their experience of having lived their entire lives in the shadow of mass shootings and in anticipation of them. By calling themselves a mass-shooting generation, they reframe the larger gun debate along generational lines. Through its elaboration of the concept Generation Parkland, this article contributes to the broader theoretical concept of Generation Z, clarifying specific ways in which this generation’s experiences of violence are communicated, and situated in relation to hierarchies between different generations in public debates.

Twitter enabled the Parkland students to participate in U.S. gun debates without third parties, such as media outlets. In doing so, the youth were able to destabilize established, generational power hierarchies. This article examines whether and how journalists were willing to use the tweeted frames of Generation Parkland in the coverage. Journalists must increasingly consider the values that elevate news stories in online environments, where readers happen upon news incidentally, and how these values might differ from traditional journalistic ones (Hermida, 2019; Mitchell et al., 2017). The degree to which the emergence of Twitter as a news source has affected the gatekeeping function of journalism has been of particular interest to researchers, as the role of Twitter has morphed over time (Groshek & Tandoc, 2017; Russell, 2019; Xu & Feng, 2014). In their study on the uses of the #Ferguson hashtag in the aftermath of the shooting of Michael Brown, Bonilla and Rosa (2015) pointed out that social media participation allowed protestors to contest mainstream media frames that vilified young shooting victims. Through participation in social media campaigns, activists could draw attention to the discussions about U.S. gun culture and structural violence toward Black people that the media was sidestepping.

In their study of the Parkland youth’s activism, Jenkins and Alejandro Lopez (2018, p. 8) offer a similar view into the disruptive effect of the social media strategies used by March For Our Lives: “Social media offers American youth a ‘no permission necessary’ means of routing around traditional gatekeepers who limit what can be said and thus what can be done.” In conservative rhetoric, open discussions about gun legislation are often framed as indecorous and disrespectful to victims, but in the case of the Parkland shooting, networked forms of protest allowed students to circumvent common media narratives and focus attention on legislation (Duerringer, 2016; Jenkins & Alejandro Lopez, 2018). This article examines how alternative frames constructed by Generation Parkland and expressed through Twitter managed to counter and replace media frames that have traditionally dominated coverage of school shootings in online journalism.

The research demonstrates that even though the voice of the Parkland youth has certainly been recognized and included in the online media, many news outlets have used it to support their own ideological frames rather than providing space for the critical frames of the young people. In other words, this article suggests that even though tweeting has given new possibilities for Generation Parkland to participate in the public debate, there are still generational power hierarchies, which are articulated through dominant frames imposed upon the frames promoted by the Parkland youth. Ultimately, this analysis at the intersection between social media and news media draws lessons for the future of journalism on how the use of tweeted teen voices can help journalists to create inclusive, intergenerational, and ethically sustainable coverage.

The research in this article builds on the premise that social media can provide a valuable tool with which young people can promote their views in the news. However, this tool is not powerful enough to overcome the ideologies shaping the production of news. Hence, the research investigates how the tweeted teen voices became subject to ideological divisions across online news media.

Another premise of the research is that young people constitute a marginal group with less possibilities to get their voices heard in the mainstream media than older generations, whose representatives have had the chance to establish positions and power in society. Therefore, the research examines how intergenerational power hierarchies were negotiated in the coverage of Generation Parkland. This study explores these questions:

RQ1: How did Parkland youth use social media to get their voices heard?

RQ2: How did the tweeted teen voices become subject to ideological divisions shaping the coverage in different online news media?

RQ3: How were intergenerational power hierarchies negotiated in the coverage of Generation Parkland?

Method

In this study, online news articles produced and published by different media in the U.S., as well as tweets integrated in these online news articles were analyzed. The core sample consisted of online news articles published by the Miami Herald, The New York Times, CNN, Fox News, and Breitbart News. While the first three news outlets have been characterized as leaning toward the political left, with their audiences representing more or less liberal views, Fox News has been regarded as promoting more conservative perspectives. Further along the spectrum, Breitbart News supports alt-right views (see AllSides Media Bias Chart, 2019; see also Mitchell et al., 2014).

The keywords used in the initial search on these sites were “Parkland school shooting” and “March For Our Lives,” specifying a time period between February 14, 2018 (the day of the shooting) and February 28, 2019 (to also include coverage on the one-year anniversary of the shooting and its aftermath). The findings were organized by relevance rather than order of appearance. The final core sample was narrowed down to a total of 280 news articles on the basis of stratified sampling, giving greater emphasis to those news sources that had produced more coverage (Miami Herald, The New York Times, Fox News, CNN) than media which had produced a smaller amount of coverage, such as the New York Post and the South Florida Sun-Sentinel. Inclusion of the Sun-Sentinel’s coverage in the sample is important, given that in April 2019 it was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in the category of Public Service for its Parkland-related reporting. According to the Pulitzer Prize board, the prize was given to this local newspaper for “exposing failings by school and law enforcement officials before and after the deadly shooting rampage at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School” (Pulitzer Prizes, 2019, para. 1). The Sun-Sentinel sample consists of “the most relevant coverage concerning the Parkland shooting,” according to their editorial board. For the Sun Sentinel’s archive, the findings were organized based on relevance (rather than chronological order) and the researchers analyzed the most relevant coverage. The New York Post places greater emphasis on entertainment than the other media analyzed here, thus allowing the research to take into account how this aspect was also manifested in the coverage of the March For Our Lives movement. According to the AllSides Media Bias Chart, the New York Post has right-leaning coverage, similar to Fox News, whereas the ideological leaning of the Sun-Sentinel has been debated. This sample, encompassing 30 news articles from each source, 60 in total, is more limited than the core sample of 280 articles in total. However, even this limited sample is sufficient to reveal the fact that tweets did not play a substantial role in their coverage.

After completing the collection of samples, a systematic coding scheme was developed to analyze how the voices of the Parkland youth and their tweeted frames were used in online coverage of the Parkland shooting. According to Merry (2020), framing is an especially important approach in the study of gun policy and related discussion (p. 16). Frames can be defined as persistent patterns of selection, emphasis, and exclusion (Gitlin, 1980, p. 7). According to Goffman (1974), definitions of social situations develop in accordance with frames of understanding. By framing, politicians and other social actors use journalists to communicate their preferred views on issues to a wider public, while journalists both use their sources’ frames as well as superimpose their own frames upon those of their sources in the process of producing news (D’Angelo & Kuypers, 2010, p. 1). In this article, deductive and inductive approaches to frame analysis were combined with frame analysis. Through a deductive approach, a number of dominant frames that have been found in mainstream news coverage concerning school shootings could be identified, such as “Culture of Violence,” “Public Health,” “Constitutional Rights,” and “Guns Don’t Kill, People Do” frames (e.g., Callaghan & Schnell 2001, Merry 2020, Steidley & Colen 2016). Melzer (2009) argues that the National Rifle Association’s (NRA) success in blocking gun control legislation is attributable to the fact that the organization began to systematically frame threats to gun rights as threats to all individual rights and freedoms (p. 224). Through an inductive approach, the research examines how the Parkland youth constructed new critical frames, reaching beyond and countering these dominant frames. All the frames were identified by specific keywords, catch phrases, and other expressions identified during initial close reading of the sample, before proceeding to systematic coding of the whole news sample. With the help of the NVivo software, all the frames were coded vis-a-vis frame sponsors and type of source (i.e., journalistic interviews, tweets, or other sourcing practices).

To detect nuances in the coverage, the research differentiates between those Parkland students promoting stricter gun laws and more conservative students, who defended gun rights, the voices and views of other social actors with “anti-gun” and “pro-gun” stances, including the parents of the Parkland students, school staff, local and national politicians and representatives of interest groups like the NRA, which is one of the most influential interest groups in U.S. politics. All these potential frame sponsors were identified with a specific code.

Additional data was gathered via the free Twitter API, focusing on the accounts of 24 students affiliated with the #MarchForOurLives movement, using the March For Our Lives official website as a source for these accounts. This data allowed the research to compare the tweeting activity of the Parkland student activists against the online news coverage; with the NodeXL Pro program, up to 3,200 tweets posted from each user between January 1, 2018 and February 22, 2019 were gathered. These tweets were analyzed quantitatively focusing on the peaks of tweeting activity.

Another important source material used when analyzing the voices of the Parkland student activists were books written by the students: Glimmer of Hope (Winterhalter, 2018) and We Say #Never Again (Falkowski & Garner, 2018). Through these books, this study was able to capture their authentic voice and the message they were aiming to deliver through social media.

Findings

The research demonstrates that the voice of the Parkland youth has been included in all of the online media analyzed. Hence it can be said that Generation Parkland has a voice that is taken into account by other generations in gun-related public debates. However, the research found that many news outlets used this voice to back their own ideological frames rather than allowing the original frames of the young people to come forth. This tendency to use the voices of the young activists to support the established positions of the news outlets could be detected on both sides of the left-right political spectrum.

As to the first research question “How did Parkland youth use social media to get their voices heard?” this study found that the Parkland youth engaged actively on Twitter and used social media to channel their criticism directly at those policy makers who they held responsible for gun-related misbehavior. They formulated a uniform message around the need for stricter gun control, centered on their specific generational experience of gun violence, which individual activists then echoed in their tweets. With their online and offline activities, the Parkland student activists succeeded in prolonging the life of the Parkland story in the news cycle. This differs significantly from the typical ways in which the media have responded to incidents of school shootings.

As to the second question, “How did the tweeted teen voices become subject to ideological divisions shaping the coverage in different online news media?” the study found that when the tweeted voices were incorporated in news texts, journalists framed the tweets in ways that caused their original context to get lost, and the youth’s frame was subjected to more powerful frames imposed by the journalists and their other sources, such as politicians or representatives of the NRA. News outlets also appeared to pick out tweets from those youths whose political views correlated with the outlet’s, excluding tweets from students who held opposing views.

As to the third question, “How were intergenerational power hierarchies negotiated in the coverage of Generation Parkland?” the study found that news outlets were eager to include the voices of Generation Parkland in their coverage. In their core message, the Parkland students emphasized their authority to speak on the subject of gun violence due to their personal experiences with it, and the notable number of tweets from Parkland students quoted in various outlets suggests the news media recognized their authority as well. However, the Parkland activists also became victims of conspiracy theories spread on right-leaning media outlets, which undermined the activism of Generation Parkland and questioned the students’ ability to operate on their own.

Tweeted Teen Voices Shaping the Media Coverage

Generation Parkland, born in the early to mid-2000s, tend to intuitively understand how to deploy social media to demand action on gun violence, and they know how to disseminate their message on social media in real time, using platforms that are familiar to them. Unlike the survivors of the 1999 Columbine school shooting, who came of age before the era of social media, or the survivors of the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in 2012, who were too young to speak out at the time, Generation Parkland is characterized by having both the means and the skills to share their message independently. Indeed, the Parkland youth have made it a point that the media should not own their narrative; it is their story, and thus it should be told by them and not by anyone else (Kasky, 2018).

During the first few days after the Parkland shooting, several students from Marjory Douglas High School formed a group and started to formulate their joint message: the U.S. needs stricter gun laws to prevent similar incidents from happening again. Following a series of mass shootings in the United States in recent years, there has been interest and attention in new legislation but this has led to almost no action, despite numerous polls showing widespread public support for measures like strengthened background checks and the banning of certain types of high-capacity gun magazines and military-style assault rifles. The NRA opposes most proposals to strengthen firearm regulations, and it is behind efforts at both the federal and state levels to roll back existing restrictions on gun ownership. Through their efforts to reach beyond the ideological debates shaping coverage on school shootings in the mainstream media, the Parkland youth constructed a critical #NeverAgain frame. While adopting influences from other commonly used “anti-gun” frames advocating restrictions to gun laws, the #NeverAgain frame built directly on the experiences of Generation Parkland, placing the Generation’s lived experiences and trauma at its center. Their #Never Again frame challenged the common frames that limit discussion to issues like mental health and the Constitution. Instead, they addressed the value of the experiences of the youth who had been involved in the shootings, and they argued that no other young people should ever again have such experiences.

Students from the March For Our Lives group reflect on the role of social media in their movement in Glimmer of Hope (Winterhalter, 2018). According to John Barnitt, Sarah Chadwick and Sofie Whitney, social media has given a platform to say what they want to say and reach millions of people: “We always had a voice, but now we had an audience” (2019, p. 46). Their posts on social media soon led to hundreds of media inquiries, and the students were pushed into the spotlight. Chadwick describes seeing President Donald Trump’s tweet in which he offered his condolences, thoughts, and prayers directly after the Parkland shooting. This made her so angry that she tweeted that the students didn’t want thoughts and prayers, they wanted policy and action. That was one of the first tweets that went viral, receiving around 300,000 likes.

Another angry voice that soon went viral belonged to Emma González, who gave a speech at an anti-gun rally on February 17, 2018, where she confidently declared that theirs is going to be the last mass-shooting generation. The frames sponsored by the NRA and right-wing politicians such as the Constitutional Rights and Guns Don’t Kill, People Do frames were claiming that tougher gun laws do not decrease gun violence. By countering these frames with the phrase “We call B.S.,” Gonzalez introduced the #NeverAgain frame and its potential to shake traditional approaches to gun violence through the lived experience of Generation Parkland. Calling for young people in favor of stricter gun control to take action and speak out against school shootings, González gained over a million followers on Twitter with her strong message. Wang et al. (2016) found that the tweets with powerful social messages had the ability to go viral and were helpful in making a networked social movement more prominent.

The Parkland activists found a clear target for their anger; they criticized the NRA and politicians who had accepted money from the group and thus lent it support. Twitter allowed the students to address representatives of the NRA and other politicians and policymakers directly, which they also did without fear. For instance, on February 23, Chadwick tweeted: “We should change the names of AR-15s to ‘Marco Rubio’ because they are so easy to buy.” This was a day after another Parkland activist, Cameron Kasky, had asked Senator Rubio (R-FL) if he would continue to take campaign donations from the NRA. Because Rubio’s answer at the town hall did not satisfy the activists, they continued the discussion on Twitter, directly addressing Rubio and further challenging him on his non-committal answer.

Social media was not just a channel for expressions of anger. Parkland activists used it as a means to coordinate activities and as a platform for messages of resistance and hope for change. The school shooting in Santa Fe on May 18, 2018 and other mass shootings after Parkland triggered reactions from the Parkland students. They sympathized, but also expressed that they were fighting on behalf of these new victims, strengthening the #NeverAgain frame by backing it up with lived experiences of more and more school shooting victims of their generation. People were also contacting the Parkland activists through social media, asking how they could donate and contribute, and what the students were going to do next (Jenkins & Alejandro Lopez, 2018, pp. 7–8; Whitney & Duff, 2018, p. 18).

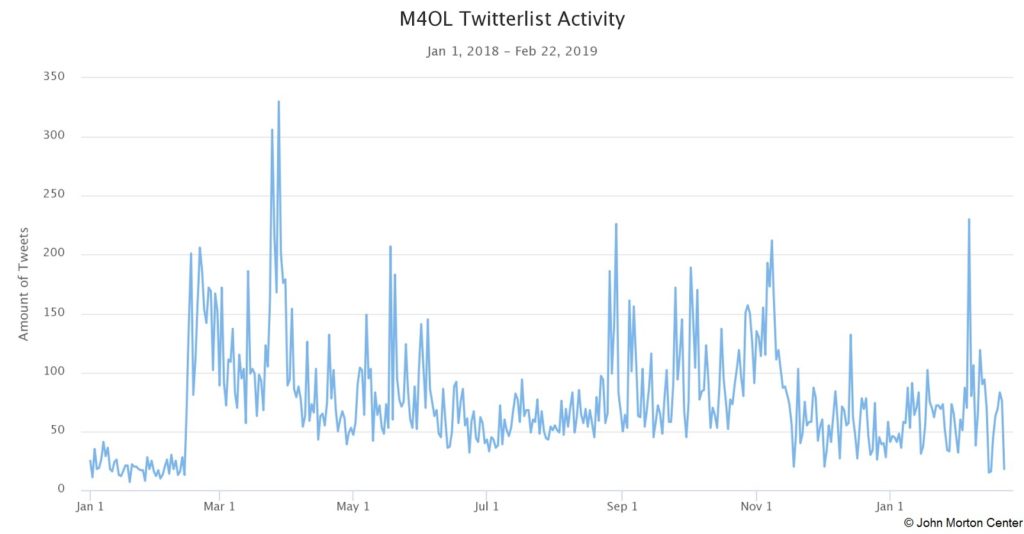

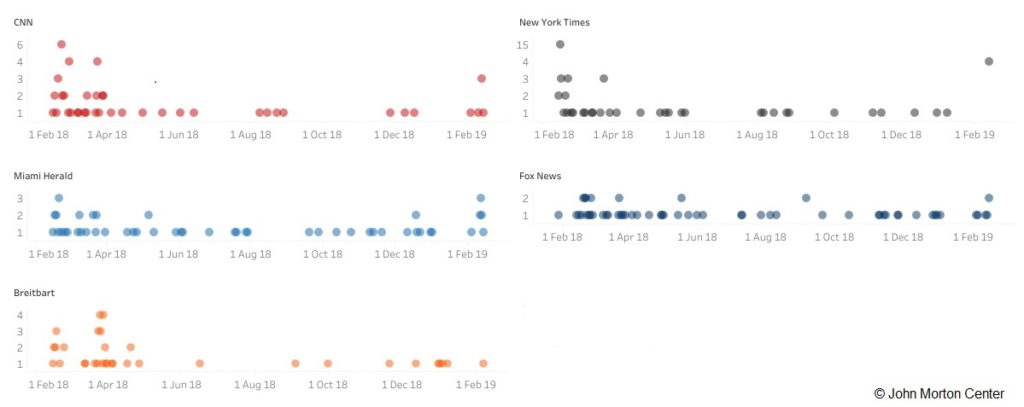

Analysis of Parkland news coverage reveals that peak media attention on the shooting coincided with the Parkland youth’s peak activity on Twitter. The duration of the coverage and tweeting activity are also linked. (See Figures 1 and 2). In other words, their tweets and other social media posts shaped the news media’s coverage of the Parkland shooting.

The peaks reflected in Figures 1 and 2 reflect the Parkland shooting (February 14) and its monthly anniversaries; another school shooting in Santa Fe, New Mexico (May 18, 2018); primary elections in Florida (August 28, 2018) and U.S. midterm elections in November. However, most of the peaks are connected to the activities of March For Our Lives movement, including the March For Our Lives demonstration in Washington, D.C. (March 24, 2018), the M4OL YouTube announcement (April 3, 2018), the National School Walkout (April 20, 2018), the Road to Change tour announcement (June 4, 2018), and the announcement of the Glimmer of Hope book (September 6, 2018). By the time the March For Our Lives protest took place in Washington, D.C. on March 24, 2018, the movement had gained millions of followers online and offline, reflected in 880 sibling events organized throughout the United States and around the world.

With their online and offline activities, the Parkland student activists succeeded in prolonging the life of the Parkland story in the news cycle. This differs significantly from the typical ways in which the media have responded to incidents of school shootings. A school shooting typically evokes a reaction sequence of a sudden moral panic but just as quickly the event is buried or fades away (Cohen, 1972, p. 9; Lindgren, 2011).

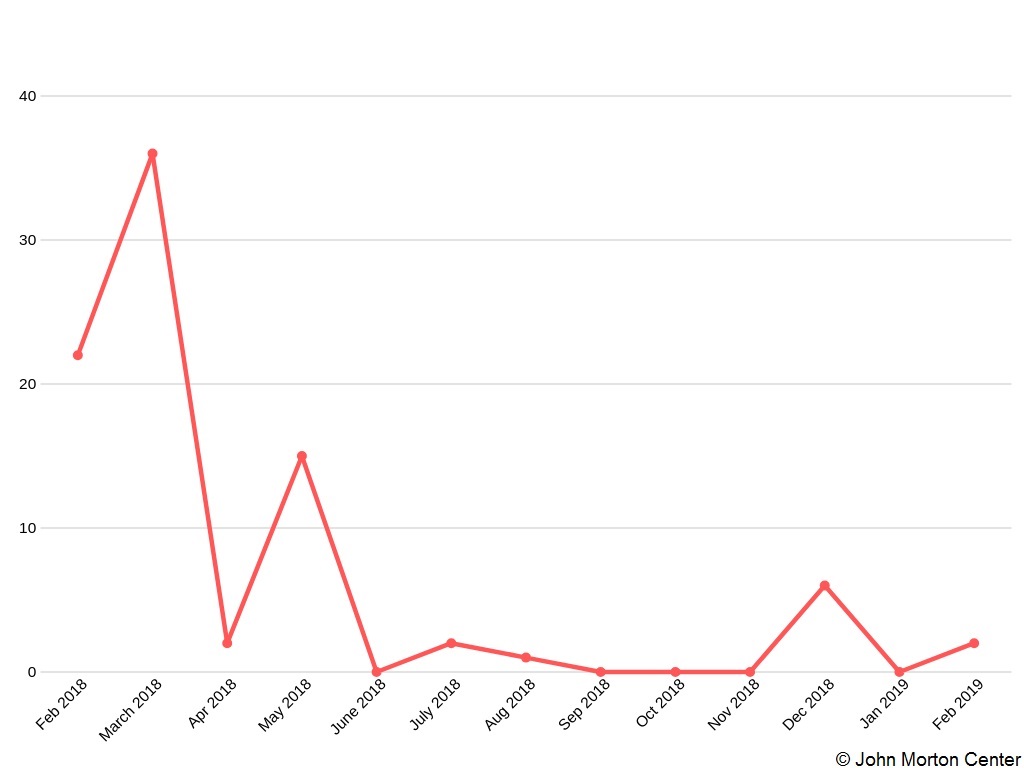

Likewise, The Trace, a non-profit organization that covers firearms issues, found that the Parkland shooting commanded more attention than previous attacks; in the three months following it, news articles mentioned gun control-related terms 2.5 times more than after previous mass shootings (Nass, 2018). A clear majority of the students’ tweets quoted in the sample of online news articles combined their lived experiences with sophisticated demands for more gun control, showing that through the #NeverAgain frame, the students were able to bring attention to many aspects of the gun control debate. The tweets covered a wide range of issues, including appeals to politicians and the NRA, calls for action, and debates about legislation from conservative proposals to stopping school violence to the repeal of the Second Amendment implying pre-existing right to keep and bear arms. Usually, coverage of most mass shootings is quickly eclipsed by other news. According to The Trace, two high-profile events sparked by the attack—a student walkout on March 14 and the March For Our Lives rally on March 24—attracted a large volume of media attention, pushing the coverage rate above the initial peak (Nass, 2018). In the research material, there is a similar peak in the Parkland students’ tweets used in online media coverage (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Number of the Parkland students’ tweets per month used in online media coverage between February 14, 2018 and February 14, 2019.

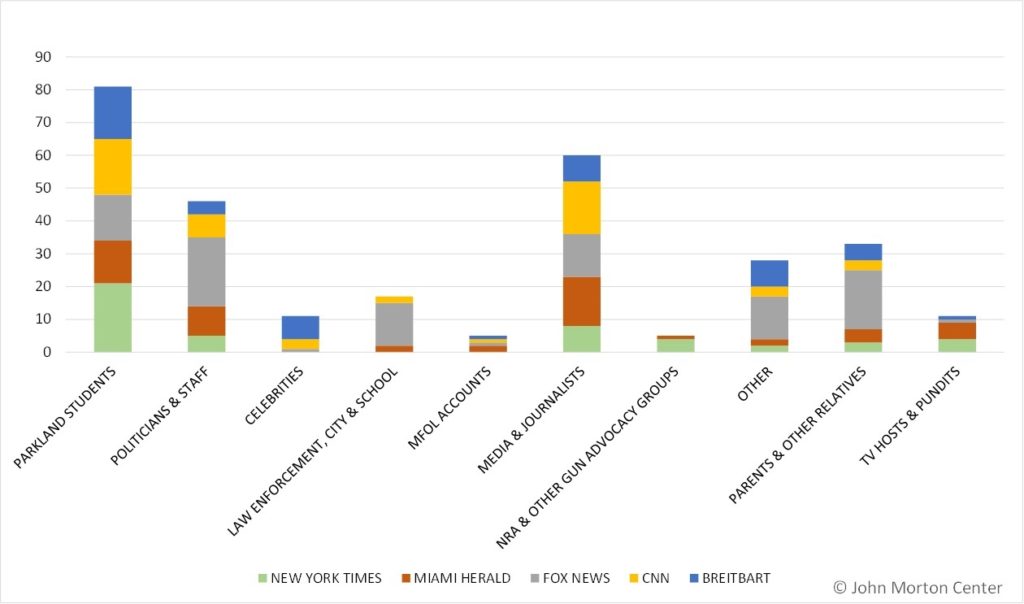

Looking at the different tweet sources included in the online news coverage, one can see that the share of tweets by the Parkland students was substantial. In the coverage of The New York Times, CNN, and Breitbart News, the students’ tweets had the highest share (see Figure 4). In particular, The New York Times, CNN, and the Miami Herald were explicit about their goal of letting the Parkland youth tell their story in their own words; for this reason, they turned to Twitter.

Studies show that when journalists gather information through Twitter, they tend to still rely mostly on the accounts of other media outlets, law enforcement officials, and other established sources of information. Journalists show reluctance in using the Twitter accounts of private citizens as sources. (Moon & Hadley, 2014; Wallsten, 2015). In addition, according to journalistic ethical codes, reporters should use heightened sensitivity when dealing with juveniles (SPJ Code of Ethics, 2014): young people should be given the chance to be heard but journalists should be aware of their vulnerability, since juveniles may not be able to recognize the ramifications of what they say (Foreman, 2016, p. 218).

Taking into consideration the journalistic tendency to rely on official news sources, it is remarkable how clearly the voices of the underaged Parkland students were heard in news coverage. They also inspired and enabled other teen voices to be heard as well. The Miami Herald published stories in collaboration with The Trace, assembling a team of more than 200 children and teenagers to research and write short portraits of every underaged victim. This way, over time, the #NeverAgain frame was sponsored and expanded in collaboration between different sectors of Generation Parkland. This leads to a more detailed discussion of how the tweeted teen voices became subject to ideological divisions shaping the coverage in different online news media.

Ideological Divisions in Tweets

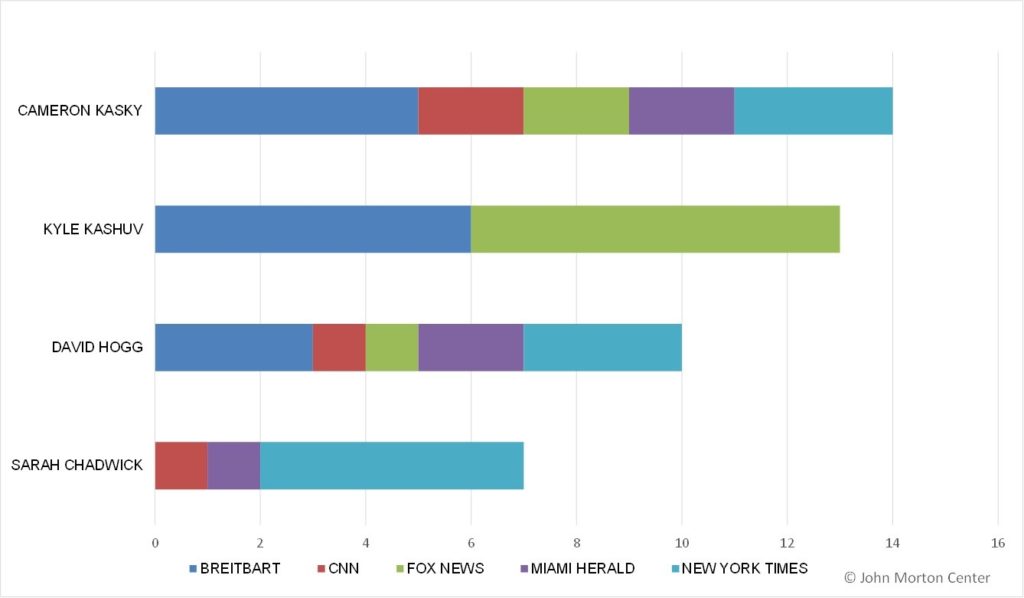

In addition to the March For Our Lives movement, other students of Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School became active after the shooting. Among them was Kyle Kashuv, a conservative student who became an advocate for gun rights. On Twitter and in his many public talks, Kashuv claimed that it is the people who are the issue, not guns. This way, through their lived experiences, voices representing Generation Parkland also contributed to the traditional ideological frames in the school shooting coverage such as the “Constitutional Rights,” and “Guns Don’t Kill, People Do” frames (Callaghan & Schnell 2001, Merry 2020; Steidley & Colen 2016). These conservative frames also became significant through contributions from some parents of the Parkland kids, especially Andrew Pollack, father of senior Meadow Pollack, who was killed in the shooting. It is hardly surprising that Kyle Kashuv and Andrew Pollack were frequently quoted in conservative Fox News and alt-right Breitbart News coverage of the Parkland shooting and its aftermath, whereas the young student activists of March For Our Lives, advocating for stricter gun laws, were cited and their causes promoted more frequently in the more liberal press (i.e., CNN, The New York Times, and the Miami Herald). Likewise, Fox News and Breitbart News regularly featured Kashuv’s and Pollack’s tweets (see Figure 5), whereas the tweets by Sarah Chadwick, Cameron Kasky, David Hogg, and other representatives of the March For Our Lives movement were more frequently included in the more liberal press.

As the previous section notes, The New York Times, CNN, and the Miami Herald explicitly emphasized the importance of respecting the authentic narrative of the Parkland youth, recognizing the traditional media’s limitations and turning to Twitter to hear their real story. In this sense, journalists did not want to impose any ideological perspective. Instead they made an effort to hear and to understand the voices of the students. Nonetheless, the fact that they wanted the story of March For Our Lives activists rather than that of Kyle Kashuv, and that the conservative media was interested in Kashuv’s views rather than those of the March For Our Lives activists, reflects persistence of the traditional ideological boundaries. At the same time, the primary purpose of the use of the #NeverAgain frame in the liberal press seemed to be to ridicule competing media who were ignoring or downplaying the frame, rather than placing primary emphasis on this frame’s potential to transform the gun debate.

Some cases may appear to be exceptions, but a deeper analysis shows that they are not. For instance, on April 5, 2018, Breitbart News published an article titled “Black Parkland Students Feel Ignored by Peers, Media” (see Nolte, 2018). The story, building on the HuffPost’s interviews with Black students from Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, describes:

The black Parkland students held a press conference last week. Tyah-Amoy Roberts, a black student who spoke at the press conference, told Refinery29, “We feel like people within the movement have definitely addressed racial disparity, but haven’t adequately taken action to counteract that racial disparity.” She said that March For Our Lives organizers did not invite her to any of their meetings, adding, “They’ve been saying, but they haven’t been doing.” The students were also angry at the media for focusing on everyone but the black students. (Nolte, 2018, para. 4-5)

At first glance, one might think that Breitbart News is actually concerned about the fate of Black Parkland students. However, as it is known to promulgate alt-right views, a much more likely explanation is that the criticism is actually directed at the liberal media, given its focus on the anti-gun students in the spotlight of the March For Our Lives movement.

Journalists also openly reflected on their own work and shortcomings. For instance, The New York Times story titled “Reporting on a Mass Shooting, Again” (see Symonds & Brooks, 2018) emphasized that even though mass shootings occur quite regularly, the newspaper’s journalists are cautious to avoid routines that would make coverage of shootings sound too similar. This story also addresses the newspaper’s critical approach toward biased sources on social media: “Twitter, especially, can be a fruitful source of details—but also a dangerous one, susceptible to being clouded by misinformation, both unintentional and not” (Symonds & Brooks, 2018, para. 10). Thus, while the newspaper acknowledges the importance of following Twitter to understand the specific message of the Parkland activists, it also expresses awareness of the fact that tweets by policymakers and other actors often reflect biased views and must be treated with caution.

Some of the tweets incorporated in the coverage did not seem relevant for the Parkland activists’ cause. Instead, they were used in the news for other purposes. For instance, when David Hogg, one of the principal activists in the March For Our Lives movement, did not get accepted into college, he was mocked by Fox News host Laura Ingraham. Hogg posted a tweet urging advertisers to boycott Ingraham’s show, forcing Ingraham to publicly apologize to him. CNN then interviewed Hogg in its “New Day” broadcast, with host Alyson Camerota shouting, “What kinds of dumbass colleges don’t want you?” By claiming that any college that did not accept Hogg was “dumb,” the CNN host offered support to Hogg’s efforts as an activist and the March For Our Lives movement. At the same time, CNN claimed distance from Fox News, which had mocked Hogg for not being accepted to these colleges. Other media, including Breitbart News, leveraged the rivalry between CNN and Fox News by drawing attention to the traditional ideological divisions between these different media—and away from gun reform and the original frames that the March For Our Lives movement was trying to advocate for.

Generation Parkland and Intergenerational Power Hierarchies

This final section of the article discusses whether the different media took Generation Parkland seriously in their coverage of the school shooting. In all of the media analyzed, the parents of the March For Our Lives founders and other active parents at Marjory Stoneman Douglas School were regularly interviewed. However, in articles focusing on March For Our Lives, the actual chance to speak was predominantly given to the students themselves. The media that most frequently gave a voice to parents rather than their children was the South Florida Sun-Sentinel. As a local news outlet, it focused more on the investigation of those found guilty of misconduct—such as the authorities who did not enter the building to protect the kids, even when hearing an active shooter in the building—and local politics rather than the national debate on gun politics, in which March For Our Lives was involved.

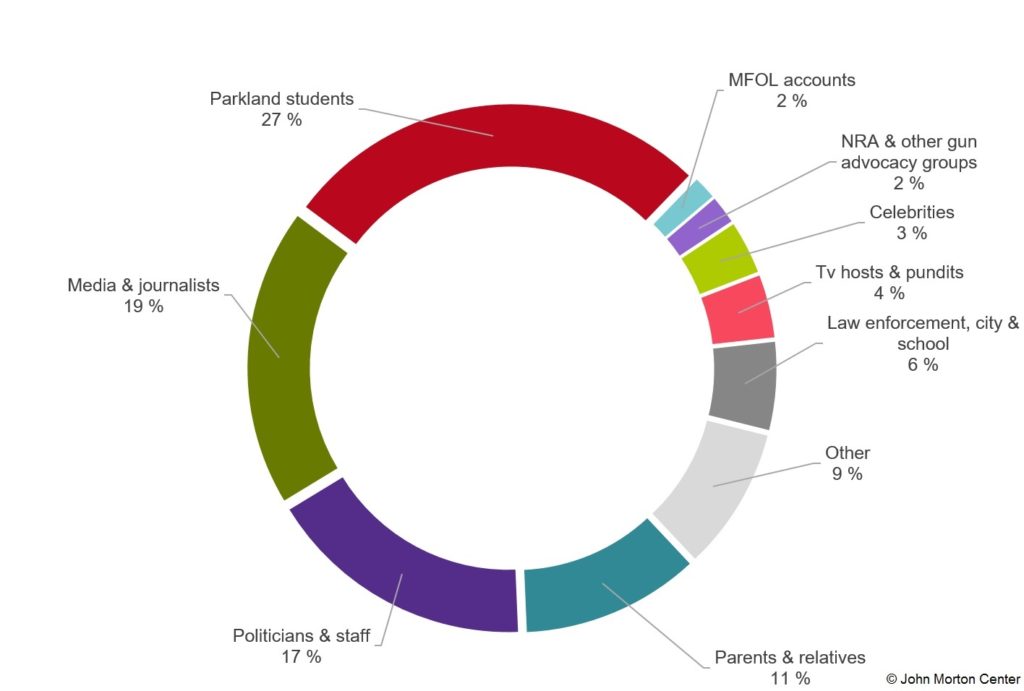

In most media, the young age of the Parkland students did not undermine their credibility, and their Twitter and other social media activism was also taken seriously, as manifested in the various tweets integrated within the news coverage. In terms of all the tweets included in the coverage of the Parkland shooting and its aftermath, the tweets of the students had the biggest share at 27% (see Figure 6). However, it is important to point out that the March For Our Lives account represented only 2%. Individual voices like stories and opinions fit better with journalistic narratives and attract more media attention. The messages of grief of the parents mainly included political messages rather than personal grievings. Overall, the media seemed ready for Generation Parkland to claim their space in the news.

There were also some pessimistic stories, however, which seemed to paint the goals of the Parkland students as idealistic and unrealistic. On the anniversary of the school shooting on February 14, 2019, the “year after” reportage by many media addressed the unmet goals, arguing that many of the expectations for Generation Parkland had been too high. For instance, in its story titled “Parkland: A Year After the School Shooting That Was Supposed to Change Everything” (see Mazzei, 2019), The New York Times interviewed students and others who pessimistically stated: “I haven’t gone back to school because I haven’t seen a change” (Mazzei, 2019, para. 14). It is nonetheless worth noting that these stories did not ridicule the March For Our Lives movement or suggest that they should stop. Instead, many of the news articles gave support for the Parkland students’ continued fight, listing the accomplishments that they had achieved. A column published in the Miami Herald on March 21, 2018 recognized the failings of older generations, titled: “May the Parkland kids forgive us for failing them so miserably” (Pitts, 2018, para 1).

The most radical form in which the capacity and authenticity of Generation Parkland were underestimated was expressed by Breitbart News, which repeated the false claim that the Parkland youth were not even students but “crisis actors” exploiting a tragedy to question the nation’s gun laws. According to such conspiracy theories, the March For Our Lives activists were puppets who had been manipulated and coached by the Democratic Party and gun-control advocates. Claims were made that liberal forces in the FBI were trying to undermine President Trump and his pro-gun, pro-Second-Amendment supporters. Such theories were provoked by the remarkable public-speaking skills of many activists, such as David Hogg, which enabled them to make compelling arguments.

Conspiracy theories represent a way to create a credibility gap between Generation Parkland and its predecessors. As Breitbart News described March For Our Lives, “A movement sparked by the shooting deaths of 17 people at Parkland High School in Florida morphed into an adult-led anti-Second Amendment protest using the March For Our Lives teens to register voters” (Star, 2018, para, 1). Connections between media’s treatment of Parkland students and other youth activists, such as 16-year-old climate activist Greta Thunberg, would be a thought-provoking line for possible future investigation. Breitbart News’s portrayal of the Parkland students as political puppets can be compared to the treatment of Thunberg by many conservative media outlets, which has included suggestions that the adults around the teenage activist are manipulating her for political gain.

While using Twitter to participate in political debate, the Parkland activists were exposed to negativity and belittling by both social media and online media outlets. Delaney Tarr describes the position of March For Our Lives student activists: “We’ve been propelled onto the national stage, where we are open to a level of criticism that no teenager should face. We are treated simultaneously like adults and children, neither respected nor understood” (Tarr, 2018, p. 23). Alfonso Calderón, one of the co-founders of #NeverAgain, expressed how the expectations leveled toward their generation are very hard:

I know that politicians have always screwed up,” he explained. “They have always said the wrong thing at the wrong time, and they’re still been taken seriously, time and time again, instead of being disavowed or disqualified for even holding an office after saying ridiculous statements. Meanwhile, my generation is – for example, Emma González, she’s an inspiration to us and she’s working for us, but, if she were to say something that was non-factual, you know she would be highly scrutinized by literally everybody, including the President. (Witt, 2018, para. 14)

Social media, which for teenagers is a common means to relieve stress, has turned into a new type of pressure for student activists, who feel that their every move is being monitored and that there are people waiting for them to make a misstep (Tarr, 2018, p. 23).

Many media outlets were explicit about their goal of including the voices of the Parkland students in their articles, and the large share of students’ tweets quoted shows that the voice of Generation Parkland was given weight in media coverage. However, generational hierarchies revealed themselves especially in conspiracy theories that questioned the ability of young activists to act on their own. The relationship between younger and older generations was recognized when the media portrayed the failings of older generations in building a better world for youth to live in. The Parkland students’ reflections on how their activism was received in the media show they are keenly aware of generational tensions that cause them to be treated as children while simultaneously facing intense pressure and scrutiny around their activism.

Conclusions

Regardless of the background of the youth behind an anti-gun movement like March For Our Lives, conspiracy theories would probably abound. However, it is true that the founders of the March For Our Lives movement do come from a relatively wealthy area: in 2017, Parkland had a population of 28,900, the median household income was $131,525 (compared to the U.S. national average of $59,039), and Parkland’s poverty rate was 3.4% (compared to 12.3% nationwide) (DataUsa, 2017). While the liberal media have taken the students’ arguments, tweets, and speeches quite seriously, others have expressed suspicions about their educational advantage. Future research could advance this question by examining the possibilities for students with less privileged backgrounds to advocate stricter gun laws across traditional and social media. Do other youth activists pertaining to the Generation Z have similar possibilities as Generation Parkland to challenge the power hierarchy of generations?

There have been expectations that digital journalism would be more democratic, transparent, novel, and participatory than earlier news technologies. But as Zelizer (2019) has observed, expectations of democratic access and sharing for all have been unevenly realized in digital technology. The use of Twitter in news can contribute to more multi-voiced coverage and intergenerational dialogue, but only if the challenges related to the structural inequities and the questions of journalistic ethics are taken into consideration in the use of tweeted voices in the coverage. When using tweeted voices, it is important to recognize the way the tweets produce stories: Instead of being told by individuals to clearly defined audiences, stories are told collectively, although not necessarily collaboratively, by large numbers of users. Through such collective actions, and the influence of elite users with a large number of followers, tweets can transform news coverage, but do not necessarily make it democratic and provide access to users with less social capital (Sadler, 2017).

This study has shown that the Parkland students’ use of social media, Twitter in particular, has significantly shaped the media coverage concerning the Parkland shooting and its aftermath. They have had their voices and tweets quoted in leading national media such as CNN, The New York Times, and the Miami Herald. Their tweets and messages have also shaped the news agenda, leading journalists to formulate headlines and story angles recognizing the students’ determination and permitting space and attention to their lived experiences on the matter. Other aspects that have often dominated the news, such as comments by politicians and authorities, have been reduced to secondary importance in comparison to the message of the students.

This said, the ideological biases of the media examined here have continued to affect coverage and play a role in the framing process, despite the voices of the Parkland students receiving a substantial share of space in online news. For instance, the more liberal sources CNN, The New York Times, and the Miami Herald systematically cited the Parkland activists pushing for more gun control, whereas the more conservative Fox News and alt-right Breitbart News frequently interviewed more conservative activists, critics of the March For Our Lives movement, and pro-gun parents. The alt-right and conservative media also explicitly expressed doubts about the credibility of the young activists. In this way, the media have not gone beyond their traditional ideological boundaries. Even when granting space to Generation Parkland, the media’s positions have remained clearly liberal or conservative. For this reason, there was a strategic advantage and rationale to the students’ use of social media as their primary means of communication, which allowed them to stay true to their own voice rather than having it filtered by mainstream media gatekeepers with their respective agendas.

It can be asked how influential the online activism of the Parkland students really was. Theories about so-called “slacktivism” posit that the use of social media for activism creates an illusion of engagement, discouraging participation in activism in offline environments (Morozov 2012). Jenkins and Alejandro Lopez (2018) argue, however, that although social media creates superficial engagement, it also makes it possible for youth to build strong social ties and generate shared perspectives, increasing the likelihood of offline action. As Gerbaudo writes, “contemporary forms of protest communication, including activist tweets, Facebook pages, mobile phone apps, and text messages revolve to a great extent precisely around acts of choreographing: the mediated ‘scene-setting’ and ‘scripting’ of people’s physical assembling in public space” (2012, p. 40).

Only four days after the shooting, the Parkland students announced their plan to organize the March For Our Lives rally on March 24, 2018, inviting people to join the movement. The fact that they were able to attract 800,000 people to the event in Washington D.C., in addition to countless sister demonstrations, suggests that their social media activism did increase offline action as well, engaging people who wanted to protest against gun violence and support action to prevent future school shootings. The Parkland youth’s Twitter activism highlighted the stagnant nature of narratives around mass shootings and caused journalists to engage with the lived experiences and political opinions of school shooting survivors. Despite some negative coverage by conservative and alt-right media, most journalists allowed the voices of the activists to come through in a positive or neutral light.

The findings of this research draw lessons for the future of journalism. The use of tweeted teen voices can help journalists in their efforts to create inclusive—and in some ways intergenerational—coverage. However, a great deal still remains to be done before fully intergenerational and ethically sustainable coverage is achieved. Given that teens clearly have things to say, they need to be taken seriously as full members of the democratic society. Future research is needed to continue to address big themes such as ideological divisions and generational hierarchies that have been raised by the research in this article.

This study built on news coverage produced and published within a year of the Parkland shooting. Future research should examine more current coverage about the March For Our Lives movement and whether and how tweeted voices have become more voluminous or silent over time.

References

2019 Pulitzer Prizes. (2019). Retrieved from https://www.pulitzer.org/prize-winners-by- year/2019

AllSides Media Bias Chart (2019). Retrieved from https://www.allsides.com/media-bias/ media-bias-chart

Barnitt, J., Chadwick, S., & Whitney, S. (2018). Creating a social media movement: Mid to late February. In D. Winterhalter (Ed.), Glimmer of hope: How tragedy sparked a movement (pp. 39–48). New York, NY: Penguin Books.

Bessant, J., (2014). Democracy bytes: New media, new politics and generational change. London, England: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bonilla, Y., & Rosa, J. (2015). Ferguson: Digital protest, hashtag ethnography, and the racial politics of social media in the United States. American Ethnologist, 42(1), 4–17. doi:10.1111/amet.12112

Burnett, J., (2003). Let me entertain you: Researching the ‘thirtysomething’ generation. Sociological Research Online, 8(4). Retrieved from http://www.socresonline.org. uk/8/4/burnett.html

Callaghan, K., & Schnell, F. (2001). Assessing the democratic debate: How the news media frame elite policy discourse. Political Communication 18(2), 183– 213. doi:10.1080/105856001750322970

Cohen, S. (1972). Folk devils and moral panics: The creation of the Mods and Rockers. London, England: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

D’Angelo, P., & Kuypers, J. (2010). Introduction: Doing news framing analysis. In P. D’Angelo & J. Kuypers (Eds.), Doing news framing analysis: Empirical and theoretical perspectives (pp. 1–13). New York, NY: Routledge.

Data USA. (2017). Parkland, Florida. Retrieved from https://datausa.io/profile/geo/ parkland-fl/

Dimock, M., (2019, January 17). Defining generations: Where Millennials end and Generation Z begins. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www. pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/01/17/where-millennials-end-and-generation-z- begins/

Duerringer, C. M., (2016). Dis-honoring the dead: Negotiating decorum in the shadow of Sandy Hook. Western Journal of Communication, 80(1), 79–99. doi:10.1080/10 570314.2015.1116712

Falkowski, M. & Garner, E. (Eds.). (2018). We say #Never Again. Reporting by the Parkland student journalists. New York, NY: Crown.

Foreman, G. (2016). The ethical journalist: Making responsible decisions in the pursuit of news. Chichester, West Sussex, England: Wiley-Blackwell.

France, A., & Roberts, S. (2015). The problem of social generations: A critique of the new emerging orthodoxy in youth studies. Journal of Youth Studies, 18(2), 215–230. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2014.944122

Gerbaudo, P. (2012). Tweets and the streets: Social media and contemporary activism. London, England: Pluto Press.

Gitlin, T. (1980). The whole world is watching: Mass media in the making and unmaking of the new left. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Goffman, E. (1974). Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience. York, PA: Northeastern University Press.

Groshek, J., & Tandoc, E. (2017). The affordance effect: Gatekeeping and (non) reciprocal journalism on Twitter. Computers in Human Behavior, 66, 201–210. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.09.020

Hermida, A., (2019). The existential predicament when journalismmoves beyond journalism. Journalism, 20(1), 177–180. doi:10.1177/1464884918807367

Jenkins, H., & Alejandro Lopez, R. (2018). On Emma González’s jacket and other media: The participatory politics of the #NeverAgain movement. Brown Journal of World Affairs, 25(1), 1–18.

Kasky, C. (2018). How it all began: February 14. In D. Winterhalter (Ed.), Glimmer of hope: How tragedy sparked a movement (pp. 1–9). New York, NY: Penguin Books.

Lindgren, S. (2011). YouTube gunmen? Mapping participatory media discourse on school shooting videos. Media, Culture & Society, 33(1), 123–136. doi: 10.1177/0163443710386527

Mazzei, P. (2019, February 13). Parkland: A year after the school shooting that was supposed to change everything. The New York Times. Retrieved from https:// www.nytimes.com/2019/02/13/us/parkland-anniversary-marjory-stoneman-douglas.html

Merry, M. K. (2020). Warped narratives: Distortion in the framing of gun policy. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press

Mitchell, A., Gottfried J., Kiley J., & Matsa, K. E. (2014). Political polarization & media habits. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.journalism. org/2014/10/21/political-polarization-media-habits/

Mitchell A., Gottfried J., Shearer E., & Lu, K. (2017). How Americans encounter, recall and act upon digital news. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www. journalism.org/2017/02/09/how-americans-encounter-recall-and-act-upon- digital-news/

Moon, S. J., & Hadley, P. (2014). Routinizing a new technology in the newsroom: Twitter as a news source in mainstream media. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 58(2), 289–305. doi:10.1080/08838151.2014.906435

Morozov, E. (2012). The net delusion: The dark side of Internet freedom. New York, NY: PublicAffairs.

Nass, D. (2018, May 17). Parkland generated dramatically more news coverage than most mass shootings. The Trace. Retrieved October 10, 2019, from https:// www.thetrace.org/2018/05/parkland-media-coverage-analysis-mass-shooting/

Nolte, J. (2018, April 5). Black Parkland students feel ignored by peers, media. Breitbart News. Retrieved from https://www.breitbart.com/the-media/2018/04/05/black- parkland-students-feel-ignored-peers-media/

Pimentel, J. (2018, December 23). 20 Young Activists Who Are Changing the World. Retrieved March 13, 2020, from https://www.complex.com/life/young-activists- who-are-changing-the-world/

Pitts, L. (2018, March 21). May the Parkland kids forgive us for failing them so miserably. Miami Herald. Retrieved from https://www.miamiherald.com/opinion/opn- columns-blogs/leonard-pitts-jr/article206152469.html

Russell, F. M. (2019). Twitter and news gatekeeping: Interactivity, reciprocity, and promotion in news organizations’ tweets. Digital Journalism, 7(1), 80–99. doi:10 .1080/21670811.2017.1399805

Sadler, N. (2017). Narrative and interpretation on Twitter: Reading tweets by telling stories. New Media & Society, 20(9), 3266–3282. https://doi. org/10.1177/1461444817745018

Seemiller, C., & Grace, M. (2019). Generation Z: A century in the making. London, England: Routledge.

SPJ Code of Ethics—Society of Professional Journalists. (2014, September 6). Retrieved from https://www.spj.org/ethicscode.asp

Star, P. (2018, June 16). Left wing adult-led March for Our lives launches voter registration tour. Breitbart News. Retrieved from https://www.breitbart.com/ politics/2018/06/16/left-wing-adult-led-march-for-our-lives-launches-voter- registration-tour/

Steidley, T., & Colen, C. (2016). Framing the gun control debate: Press releases and framing strategies of the National Rifle Association and the Brady Campaign. Social Science Quarterly 98(2), 608–627 doi: 10.1111.ssqu.12323

Symonds, A., & Brooks, R. (2018, February 16). Reporting on a mass shooting, again. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/16/ insider/reporting-mass-shooting-parkland.html

Tarr, D. (2018). Pushed into the spotlight. In M. Falkowski & E. Garner (Eds.), We say #Never Again. Reporting by the Parkland student journalists (pp. 21–24). New York, NY: Crown.

Wallsten, K. (2015). Non-elite Twitter sources rarely cited in coverage. Newspaper Research Journal, 36(1), 24–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739532915580311

Wang. R., Liu, W., & Gao, S. (2016). Hashtags and information virality in networked social movement. Online Information Review 40(7), 850–866. doi.org/10.1108/ OIR-12-2015-0378

Whitney, S., & Duff, B. (2018). Becoming a team: February 15 and 16. In D. Winterhalter (Ed.), Glimmer of hope: How tragedy sparked a movement (pp. 13-21). New York, NY: Penguin Books.

Winterhalter, D. (Ed.). (2018). Glimmer of hope: How tragedy sparked a movement. New York, NY: Penguin Books.

Witt, E. (2018, February 19). How the survivors of Parkland began the Never Again movement. The New Yorker. Retrieved from https://www.newyorker.com/news/ news-desk/how-the-survivors-of-parkland-began-the-never-again-movement

Wyn, J., & Woodman, D. (2006). Generation, youth and social change in Australia. Journal of Youth Studies, 9(5), 495–514. https://doi. org/10.1080/13676260600805713

Zelizer, B. (2019). Why journalism is about more than digital technology. Digital Journalism, 7(3), 343–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2019.1

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Helsingin Sanomat Foundation. We thank Jaakko Hirvioja, Project Researcher, for assistance with research material and graphs, Albion Butters and Mila Seppälä for the great help with language editing and the staff of John Morton Center for North American Studies, University of Turku, for comments that greatly improved the manuscript. We would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers of this article for their suggestions and feedback.

Kirsi Cheas received her Ph.D. from the University of Helsinki, Finland in 2018. Her research has focused on cross-national comparisons of ways in and extent to which journalists incorporate diverse voices and views in the news. She is particularly interested in how different technological developments and digital tools can enhance marginal people’s possibilities to have an impact in society.

Maiju Kannisto is a cultural historian and media scholar with experience in media industry and journalism studies. She received her PhD in Cultural History from the University of Turku, Finland, in 2018. Most recently, she has been studying news coverage of school shootings, the dynamic relationship between legacy media and social media, and ethical journalism at the John Morton Center for North American Studies.

Noora Juvonen received her B.A. in Area and Cultural Studies from the University of Helsinki in 2018 and is currently working toward her master’s in American Studies at the University of Southern Denmark. Her research interests include American youth activism and the study of online activist communities.