Quality, quantity and policy: How newspaper journalists use digital metrics to evaluate their performance and their papers’ strategies

By Kelsey N. Whipple and Jeremy L. Shermak

[Citation: Whipple, K., & Shermak, J. (2018). Quality, quantity and policy: How newspaper journalists use digital metrics to evaluate their performance and their papers’ strategies. #ISOJ Journal, 8(1), 67-88.]

Through insights from 521 editorial employees at 49 of the largest newspapers in the United States, this research explored the way journalists use audience analytics data, social media responses, newsroom strategies, performance evaluations, personal and professional feedback and other newsroom and content factors to make decisions about their readers, content and professional performances. The survey included both qualitative and quantitative assessments, and the researchers applied an iterative textual analysis to the in-depth answers to understand journalists’ understanding of and fears about their newspapers’ digital strategies.

When “all the news that’s fit to print” became all the news that’s fit to publish in the unfathomable amount of digital real estate afforded by the Internet and displayed across various new media platforms, the standards and routines journalists use to measure what, exactly, is fit to go where adapted to the new realities (Allan, 2006; Bivens, 2008; Singer, 2004) as well. The Internet has adjusted and increased the number and types of needs journalism gratifies for its audiences (Dimmick, Chen, & Li, 2004). As those standards and needs have shifted, so have shared perceptions of who’s fit to create journalism and how, exactly, to judge that person’s fitness, or their professional competence and performance. The digital age has brought with it many challenges, opportunities and changes for the professional practice of journalism. Revolution in the craft has even altered the way journalists consider and measure the success of their stories and other content online (Anderson, 2011; MacGregor, 2007; Vu, 2014). Traditional measures such as print circulation and pick-up rates, while still relevant, tell journalists nothing about their online audiences, which might not overlap—entirely or at all—with their print readership. Today, online audiences can be conceptualized via demographic data gauged through a variety of web metrics—page views, monthly active users, unique visitors, pages per visit, time on site, social media engagement and more—across a variety of tools and platforms—Google Analytics, Chartbeat, Facebook Insights, Sprout Social, Social Flow, Hootsuite, Tweetdeck, etc.

Journalists use those web performance metrics to make gatekeeping decisions about online content, including prioritizing successful content on the homepage and other valuable parts of the website and increasing the media richness of that content in hopes of duplicating or spreading its success (Anderson, 2011; Vu, 2014). The degree to which journalists understand the monetization and financial impact of their readers, through those web metrics and other evaluating factors, influences how much they pay attention to and incorporate audience responses into their content (Tandoc, 2013). However, most research to date has focused on how these metrics influence the decisions editors make about content geared toward an audience.

This study explores the value and impact of audience analytics data on journalists’ professional roles by examining the ways journalists measure and interpret the success of their professional performances. It considers how editors measure their output and how those means of measurement correspond with the journalists’ knowledge and perception of their publications’ digital strategies. Through a detailed survey sent to a purposive sample of journalists who work in a variety of editorial positions at 49 of the top U.S. newspapers, 521 American journalists assessed the importance and influence of various web performance metrics, including online audience size, social media shares and likes, total time spent on their content online and reader comments, as well as qualitative performance indicators, including the quality of the content, the impact of the content on the community and recognition from the public and other journalists.

The purpose of this study is to understand how newspaper journalists evaluate their own performances and those of their institution’s digital strategies, both of which hold significant potential impact for the content they produce and the ways in which it is published. In doing so, this study expands the application of the hierarchy of influences (Shoemaker & Reese, 2013) in the digital age, particularly the influence of the organization and the audience in online journalism, as well as the potential impact of qualitative and quantitative performance metrics on the communications routines level of gatekeeping theory (Shoemaker & Vos, 2009). Both applications serve a practical purpose for the public by helping to expand a shared understanding of the institutional values and professional motivations of journalists and the ways they value and interpret their roles during an increasingly digitally focused era of the industry.

Literature Review

The Hierarchy of Influences

Journalists make professional decisions every day based on a number of internal and external factors that Shoemaker and Reese (2013) have explored and codified as the hierarchy of influences. Their hierarchy provides the framework for this paper, because it helps to explain the means through which the content that journalists create is affected by the attitudes and norms of the journalists who create it and the organizations to which they belong. The hierarchy of influences is underlined by a series of basic assumptions, including the idea that journalists’ attitudes and the newsroom osmosis (Breed, 1955) process through which they learn institutional routines influence the creation of news. That influence is significant to this study, which analyzed journalists’ use of several means of judging quality of their content, their own performances and their attitudes about both.

This study explores the priorities of journalists at three levels of the hierarchy of influences: organizational, individual and routines. At the organizational level, the structure of the journalists’ workplace, the institutional standards and character of that organization and the editors and other superiors who enforce the processes and priorities of the publication combine to exert an organizational influence on the content produced by that publication (Shoemaker & Reese, 2013). Most organizations prioritize their economic goals—the need to make money in order to continue creating content (Shoemaker & Reese, 2013). This economic motivation is particularly strong in the era of Internet-based publications and failing and reactionary digital business models (Chyi & Tenenboim, 2017). For newspapers, this means a focus on the relationship between content and advertising. In this article, economic goals are manifested in the idea of measuring audience size and growth through online metrics. Other means of measuring economic health and growth include subscriptions (both print and digital), the size of a paper, the size of its staff and the revenue of the company that owns the paper.

The structure of an organization and the processes routinized within it also impact content creation. According to Shoemaker and Reese (2013), “Organizational structure is the playing field on which employees compete for scarce resources” (p. 155). This structure helps employees navigate conflicts and guarantee promotion and progression within the organization, and it is through this structure that they come to learn what is expected of them in their positions (Breed, 1955). The priorities of the organization tend to overrule those of the individual journalist (Epstein, 1973). This study explores the implications of the structure of an organization on journalistic content through survey questions about the means through which organizations determine the success of their employees. According to Shoemaker and Reese:

Whenever media workers deduce what their supervisors want and give it to them, de-facto control has been exercised. Whether policies are overt or covert, if employees do not come to an understanding of acceptable and deviant behaviors, they are either fired or leave for a more palatable organization. (2013, p. 159)

The way journalists work also influences the content they produce. The routines level of analysis considers the impact of the “patterned, repeated practices, forms, and rules that media workers use to do their jobs” (Shoemaker & Reese, 2013, p. 165). These routines may be enforced by an organization or guided by individual attitudes and preferences, and they can also be guided by the audiences (Loosen & Schmidt, 2012) that media companies spend a great deal of time and funding tracking (Shoemaker & Reese, 2013). Analysts within these companies study the audience’s demographic information and behaviors to understand what types of content they consume and how they respond to it. “Time spent, number of clicks, and page views allow organizations to directly measure several dimensions of audience interest in content and advertisements” (Shoemaker & Reese, 2013, p. 170). The importance of the audience has expanded since the media made the transition to the Internet (Shoemaker & Reese, 2013). This study explores the routines level of analysis through the journalists’ attention to their audiences and peers, including through online metrics, social media engagement and metrics, reader responses and reception by peer journalists.

News Values and the Individual Level

Another accepted standard by which journalists make decisions about their content is a standard system of news values, the elements that give a story its importance and motivate a journalist to pursue it. According to Shoemaker & Reese (2013), “News routines provide a perspective that often explains what is defined as newsworthy in the first place … Through their routines, [news workers] actively construct reality” (p. 182). This construction is routinized within the newsroom and within the academic study of journalism, and news values have been studied widely by scholars including Shoemaker and Reese (2013), O’Neill and Harcup (2009) and Schultz (2007). Traditional news values contribute to the level of quality journalists perceive within their content; these values include “prominence and importance,” “conflict and controversy,” “the unusual,” “human interest,” “timeliness” and “proximity” (Shoemaker & Reese, 2013, p. 171). Determining what content is newsworthy and what isn’t, “is a cognitive exercise, a judgment that any person can make” (p. 173).

However, journalists make that determination based on their understanding of the news values they have been institutionally trained to recognize and value. In this way, “journalists work within a complex institutional and cultural environment that leaves its imprint on the daily news. Decisions are not made by autonomous journalists, but are rather the product of the framework of social relationships at the newspaper” (Clayman & Reisner, 1998, pp. 196-197). This study analyzes how journalists assess the quality of journalistic work and how they use that value to gauge the performance of individual journalists.

Gatekeeping Theory

A more detailed means through which journalists make decisions about what to cover and how to cover it can be understood with the help of gatekeeping theory. Shoemaker and Vos (2009) parsed gatekeeping theory into many of the same levels reflected in the hierarchy of influences, including the organizational and communication routines domains, which apply directly to this study. The audience is an important consideration in the practice of gatekeeping, despite the fact that journalists usually have “modest exposure to their audience” (Shoemaker & Vos, 2009, p. 53). This exposure is sifted through audience typifications created by editors (Sumpter, 2000), who use these mental models of their audiences as a standard for how to make decisions about what content to create for those audiences. In this way, “the audience has come to influence news content in as much as journalists develop routines based on assumptions or intuitions about the audience” (Shoemaker & Vos, 2009, p. 54). This study uses the relationship between gatekeeper and audience as grounding to explore how audience engagement and reception affect how journalists measure and define the success of quality journalism.

Measuring the Quality of Journalism

There are many ways, both quantitative and qualitative, to measure the quality of journalistic content. Measuring the quality and success of journalism is critical because “good” journalism is believed to “lead to better decisions by citizens and more accountability of government” (Lacy & Rosenthiel, 2015, p. 9). The glaring question, then, is: What is considered “good”? Journalistic scholars and professional practitioners define quality journalism differently.

Scholars have historically measured journalistic quality through the notions of demand and production. Demand considers the reasons why consumers seek journalism and how it serves particular needs—a perspective that often includes the theoretical framework of uses and gratifications (Lacy, 2000; Ruggerio, 2000). Meanwhile, production relates to an assessment of content whereby journalists can control elements of their work to meet the presumed needs of the audience in terms of civic and cultural influences (Lacy & Rosenthiel, 2015).

For practitioners, including reporters and editors, the criteria that determine quality may differ from newsroom to newsroom. Bogart (1981) attempted to solidify practitioners’ definitions of quality, taking a quantitative approach to measure journalism quality in print newspapers by creating a scale that incorporated such data as average length of story, number of letters to the editor per issue and the presence of an astrology column. While laying a foundation for future quantitative measures to come, Bogart’s (1981) scale is predictably antiquated in the age of digital journalism. Web platforms have given both scholars and journalists access to metrics capable of quickly and accurately measuring audience engagement. Both reporters and editors now regularly include these metrics in assessments of their publications and personal work (Lacy & Rosenthiel, 2015).

Use and Perception of Metrics in the Newsroom

Today, metrics, social media and online surveys enable journalists to create a more realistic picture of their audiences in the digital age (Tandoc & Ferrucci, 2017). Despite these new insights, literature suggests that analytics are used most often to make changes in routines and story distribution. For example, journalists reported that they are influenced by audience metrics and Twitter feedback in choosing what to write about (Tandoc & Ferrucci, 2017). Hanusch (2017) found that some reporters regularly tracked the metrics of their individual stories, even outside of regular working hours. Some reported going as far as adjusting elements of their stories online if they were not receiving enough page views. They would “slightly adjust stories using a different headline, angle or image to achieve better engagement or a wider audience” (Hanusch, 2017, pp. 1578). Journalists are more likely to write follow-ups and continue coverage of stories that received higher degrees of audience engagement as evidenced by digital metrics (Vu, 2014; Welbers, van Atteveldt, Kleinnijenhuis & Ruigrok, 2016).

Journalists may also give more attention to metrics because of the lingering sense of financial instability in the industry (Tandoc, 2015). These metrics may quantify a sort of “symbolic capital” (p. 785) that represents meeting audience preferences, which, in turn, is believed to assess economic capital, therefore improving the economic stability of their publication (p. 793).

Despite the availability of seemingly helpful insights, journalists’ attitudes about metrics vary greatly. Tandoc and Ferrucci (2016) found that “the strongest predictor of intention to use audience feedback is the journalist’s attitude toward such practice” (p. 155). Karlsson and Clerwall (2013) believe that the value of analytics is driving journalists away from their norms, perhaps having a greater impact than the journalists who participated in their study would like to admit. Agarwal and Barthel (2015) found that journalists felt that reliance on analytics as a judgment of their work may lead to a lower quality of journalism, due in part to a lack of cohesion within their organizations, suggesting that “higher ups” offered little guidance or feedback.

And that assumes that journalists are acquainted with analytics data for the work they create, which is determined through institutional hierarchy. Access to and use of metrics depends significantly on an individual’s position of power in the newsroom. Those with more senior, authoritative positions in the hierarchy—such as editors—are more likely to access the data, despite it being available to everyone in the newsroom (Hanusch, 2017, p. 1577).

Editors express a keen focus on analytics because these data represent revenue in a time during which there is great concern about the future of financial stability in journalism (Chyi & Tenenboim, 2017). Editors have admitted that stories receiving the most clicks on their websites and the most attention on their social media accounts were more likely to be updated and followed-up on through future successive stories on the same topic (Tandoc, 2014). These editors equated higher web traffic with “a job well done” (Tandoc, 2014, p. 569), indicating a relationship between digital metrics and perceived quality of content.

Using Metrics to Define Journalistic Quality

Journalists have shifted their assessments and definitions of quality over time because of changes in their audiences and advancements in media technology (Tandoc & Ferrucci, 2017). The emphasis on data as an evaluation of journalistic quality is exemplified by the hiring of data-dedicated analysts at traditional outlets such as the New York Times, as well as digital-native outlets such as BuzzFeed and Vox (Lacy & Rosenthiel, 2015). Unsurprisingly, digital-only publications have more robust analytics with open access to many, if not all, in the newsroom. Print publications—even those with an online presence—use more basic analytics (such as lists of the top 10 most popular stories of the day) with more limited access (Hanusch, 2017). Both today and in the coming years, studying the effects and consequences of metrics on the newsmaking process will be critical in this era of “big data” (Boczkowski, 2015).

Despite the proliferation of metrics in measuring the quality of content, these approaches are not without limits. One very prominent limitation is the absence of a true qualitative assessment of the work, where nuances in the stories may not be detected strictly by data analysis and might instead require human assessment. For example, Tandoc and Ferrucci (2017) found that evaluations from superiors were more influential than metrics in altering news production routines. However, there is little research about how evaluations from superiors blend with metrics to help journalists define quality. One example of integrating human assessment and metrics is the American Press Institute’s “Metrics for News” program. This tool first “tags” stories based on editors’ assessments and then uses engagement metrics to essentially see if the audience agrees with them (Lacy & Rosenthiel, 2015).

In their overview of many studies of journalism quality assessments, Rosenthiel and Lacy (2015) found that assessing journalist quality must take a multi-faceted approach in which both qualitative and quantitative considerations are factored in to the assessment. Although a great deal of scholarship has been devoted to how metrics alter work routines and content selection (e.g. Hanusch, 2017; Tandoc & Ferrucci, 2017; Welbers, et. al., 2016), an examination of how journalists view the quality of their work in today’s data-driven newsrooms is lacking. This study seeks to fill that gap and build upon previous work to answer the following research questions:

RQ1: What qualitative and quantitative values do news organizations use to think about and measure the success of their content?

RQ2: How often do editors and superiors use qualitative and quantitative values to gauge the performance of journalists?

RQ3: To what extent do digital performance metrics impact the content journalists create, and in what ways?

RQ4: How do print- and web-focused journalists evaluate the success of their newspapers’ digital strategies?

RQ5: What concerns do journalists express with their newspaper’s digital strategies and the state of digital journalism?

Methods

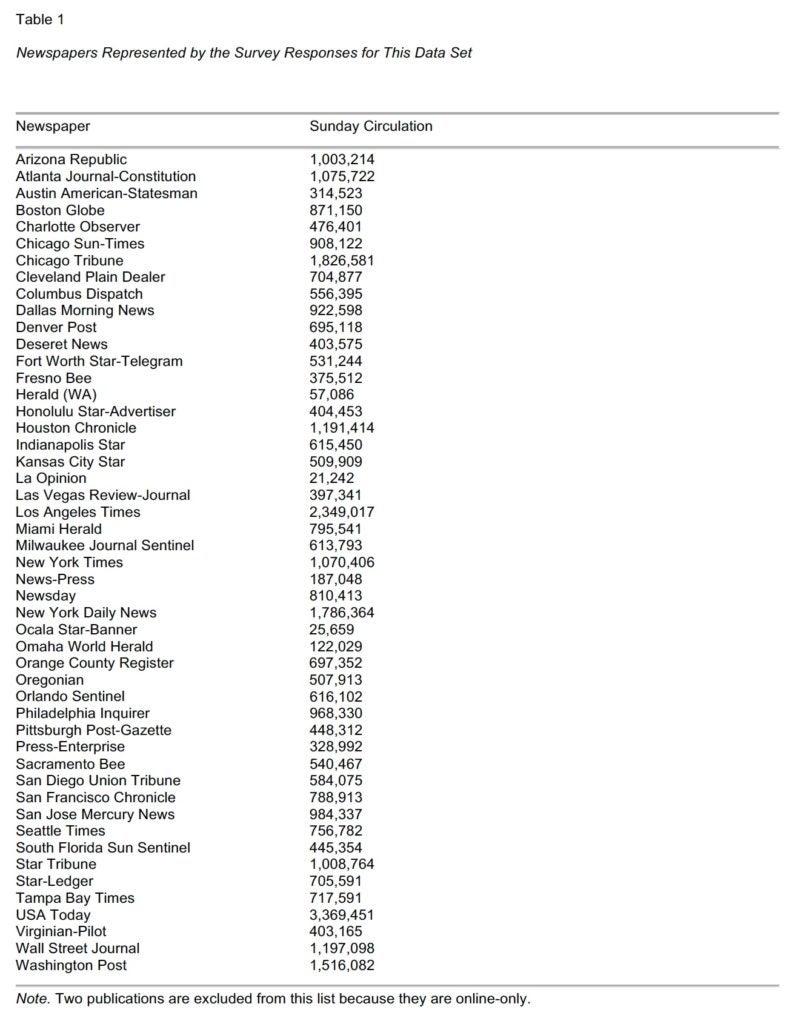

This study was conducted through a survey administered via the online survey software Qualtrics and emailed in December 2016 and January 2017 to U.S. newspaper journalists working at the top 50 U.S. newspapers by Sunday circulation, according to the Alliance for Audited Media’s (AAM) Q3 2016 report, of 100,000 or more. Sunday circulation was selected as the key factor in selecting newspapers to include in this research because the Sunday issue traditionally is the most popular. For the purpose of this research, which asks respondents to identify whether their roles are print- or digital-focused, the existence of both products was necessary for inclusion. Therefore, two newspapers were eliminated from the original AAM list for the reason that they are online-only and do not offer a print product. After eliminating online-only entities, the Wall Street Journal was added to the list because while it still operates both in print and online, it was excluded from Sunday circulation numbers after discontinuing its Sunday edition in 2015 (Barthel, 2016). Lastly, the authors elected to include La Opinion, the highest-circulating Spanish-language newspaper in the U.S., to increase the inclusivity and diversity of the corpus.

This study surveyed journalists working at the top U.S. newspapers, according to their Sunday circulation, about their use of multiple qualitative and quantitative values to measure the success of their content and the impact of digital audience metrics on their content, as well as the values editors use to gauge the performance of the journalists below them. For the quantitative questions, we used median and interquartile range as measures of central tendency due to the fact that the data was not normally distributed. The following summary describes the results in relation to the research questions for this project.

Newspaper contact information was obtained using Cision, a database containing more than 1.6 million media contacts that pulls information from publicly available sources such as social media. The final list included 5,217 journalists. Eliminating 23 bounced emails, a total of 5,194 journalists were asked via their professional email accounts to complete the Qualtrics survey. Of that total, 521 journalists from 49 different U.S. newspapers filled out the entire survey (a response rate of approximately 10%) during the six weeks it was available (see Table 1 for list of publications).

This response rate represented 1.6% of the 33,000 full-time newsroom employees in the United States (Barthel, 2016). Among respondents, among those indicating gender (n = 335), 59.1% (n = 198) were male and 40.9% (n = 137) were female. There were 189 respondents who elected not to share their gender. The average age among all respondents who elected to share (n=322) was 50.08 years. Females electing to share their age (n = 129) averaged 47.59 years while males disclosing their ages (n = 192) were an average 51.69 years old.

The survey consisted of 67 cross-sectional questions designed to assess journalists’ understanding of their newspapers’ print and online readership, as well as the degree to which the journalists know about their publication’s digital strategies and how they assess those strategies. Questions about their publications’ digital plans included, “On a scale of 1 to 7, how much do you think you know about your newspaper’s digital strategy?” and, “How well do you think your newspaper’s digital strategy is working? [‘Not at all’ to ‘Very much’].” Additional open-ended questions probed for details about their thoughts and thought processes.

In addition, questions asked the journalists to assess how both quantitative and qualitative factors are used within their newsrooms to judge the performance of the journalism they create. Sample questions in that area included, “How often do you use the following [page views, time spent on content, social media shares and likes, readers’ online comments/other (please specify)] to track readers’ responses to the content you produce?” and “To what extent do you think online metrics affect the content you produce? [‘Not at all’ to ‘Very much’].” Using the same metrics in addition to more qualitative options (quality of the content, impact of the content in the community and recognition from peer journalists) the journalists were asked to analyze the frequency with which those metrics are applied in their newsrooms and the extent to which they believe they should be used. The same scale of “Not at all” to “Very Much” applied to questions including, “How often do your editors and superiors use the following to gauge your performance as a journalist?” and “Do you think your news organization should use the following to gauge the value of content?” The researchers then analyzed the frequencies of the survey results and the correlations between the journalists’ stated actions and perceptions. The quantitative survey results were analyzed using the statistical software SPSS.

Additionally, the survey also included a number of open-ended write-in questions, which were created with the goal of allowing the respondents to answer more complicated questions with detailed answers they could steer in any direct they’d like. The write-in questions had no maximum text limit. This study found footing in one specific open-ended survey question, which was posed as: “How well do you think your newspaper’s digital strategy is working? Why or why not?” To achieve a deeper understanding of the way journalists perceive their newspapers’ digital strategies and their concerns about the state of the newspaper industry online in light of those strategies, the researchers performed a textual analysis of the write-in responses (n = 230) to the survey question asking journalists to assess the success of their newspapers’ digital strategies. The results of this textual analysis are explored in RQ5.

Results

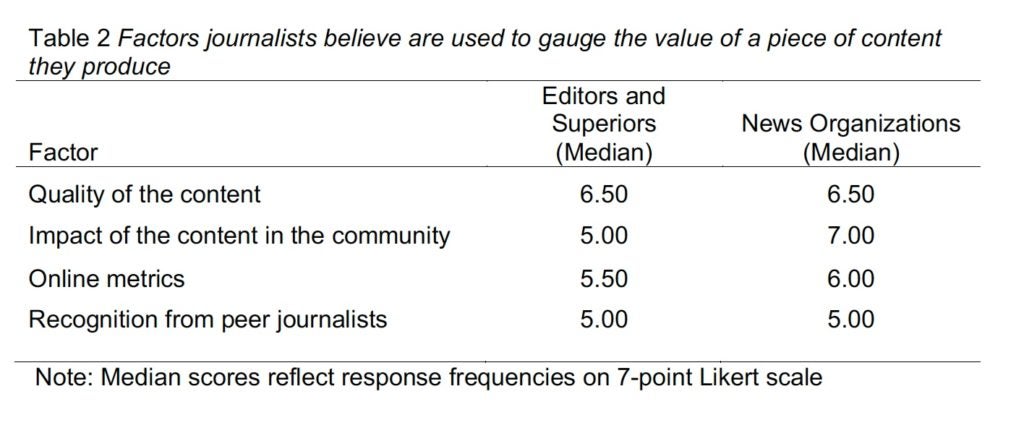

RQ1 asked what qualitative and quantitative values news organizations use to think about and measure the success of their content. According to the results, both editors and news organizations highly value online metrics. Indeed, online metrics ranked the highest for editors when journalists were asked to indicate the priorities of their superiors. When asked what their new organizations use more generally, the journalists agreed (Mdn = 7, IQR = 1) that their organizations most often use the perceived impact of the content on the community—a qualitative measure—as the most important means of assessing the value of their journalism. Organizations were also perceived to value the quality of the content (Mdn = 6.5, IQR = 2) and online metrics (Mdn = 6, IQR = 4), though online metrics did not top organizational measures of gauging content the way they topped editors’ priorities.

While the organizational level is believed to focus on the impact content has on the community, the editors and people in power in the newsrooms were seen as more likely to focus on quality. The journalists strongly believe their editors and superiors use quality of content (Mdn = 6.5, IQR = 2) as the primary factor in gauging its value. After that top value, they use the impact of the content on the community (Mdn = 5, IQR = 4) and online metrics (Mdn = 5.5, IQR = 4) equally often to gauge the value of content.

Both the organizations and the editors are equally unlikely to be influenced by recognition from peer groups (Mdn = 5, IQR = 3) when gauging the value of their content.

In the survey, questions about this topic asked journalists to write in their own, more detailed and open-ended responses outside of the multiple-choice options available. This allowed the journalists to form their own answers and include multiple levels of the hierarchy of influences, if they desired. In a write-in response, one journalist stressed that online metrics should not be an optional consideration. Instead, they must be mandatory. And maybe they already are: “Do they have a choice in this day and age?” Another journalist wrote that superiors use the content’s contributions to advertising revenue to judge its value, while someone else wrote that editors should consider gauging the “impact of stories on possible advertising appeal, eg. boxing events.” These two responses suggest that advertising revenue may be an additional consideration worth studying when it comes to how journalists measure the performance of their content, but one response suggests that it shouldn’t be taken into account as such while the other suggests it should.

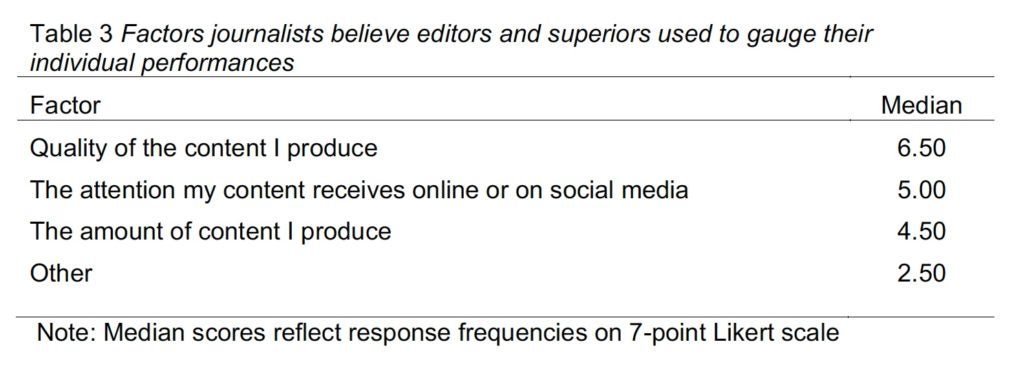

RQ2 examined how often editors and superiors use qualitative and quantitative values to gauge the performance of journalists. For this question, journalists indicated how often their editors use values such as the amount of content produced, the quality of that content, the attention it receives online and on social media and other factors to gauge their professional performance. The quality of the content (Mdn = 7, IQR = 3) was identified as the most important consideration. The journalists indicated that their editors do value the attention content receives online and on social media (Mdn = 5, IQR = 1), as well as the amount of content they produce (Mdn = 4, IQR = 2), though much less—and in that order of significance. For this, question, too, journalists wrote in their own suggestions for items they believe their editors use to measure their performance at work. Notably, one journalist mentioned that, because he or she is a freelance contractor, editors do not use online metrics as a means of evaluating his or her performance, though that is used to evaluate all other journalists in the newsroom. Another complained about the lack of feedback from editors in general.

RQ3 examined the extent to which digital performance metrics impact the content journalists create, and in what ways. Journalists were asked how much digital performance metrics influence the content they create. On a scale of not at all (one) to very much (seven), the median score was a five (IQR = 3), indicating that digital metrics are an important factor in the decisions journalists make about their content.

RQ4 analyzed how print- and web-focused journalists evaluate the success of their newspapers’ digital strategies. We sought to gauge journalists’ knowledge of their publication’s digital strategies based on their self-determined dominant platform—print, online, or hybrid (both print and online)—as well as how they evaluated the success of that strategy. Unsurprisingly, journalists who identified as online-dominant were most knowledgeable about their publication’s digital strategies (Mdn = 6, IQR = 1). Hybrid journalists were the second-most knowledgeable (Mdn = 5, IQR = 2), followed by print journalists (Mdn = 4, IQR=2). In general, the journalists surveyed indicated a mid-range level of satisfaction with the effectiveness of their newspaper’s digital strategies. Online-focused journalists were most likely to believe their newspaper’s digital strategies were working, while print-focused journalists were least likely. Journalists who identified as falling into print-web hybrid responsibilities fell in the middle. Using ordinal regression analysis, we found that journalists’ knowledge of their newspapers’ digital strategies is a strong indicator of their beliefs that those strategies are working (Γ = .392). The more journalists know about their paper’s digital strategy, the more likely they are to believe that strategy is successful.

RQ5 explored the types of concern journalists express with their newspaper’s digital strategies and the state of digital journalism. We asked journalists to assess their newspaper’s digital strategies and defend their answers by explaining why they were working or why they were not. The goal of this question was to understand the thoughts and processes of journalists when it comes to interpreting their newspaper’s digital strategies—and their own positions and job satisfaction as they relate to those strategies. This question also provided respondents with the open-ended opportunity to share their concerns with their newspaper’s digital plans, and many chose to contextualize those concerns within larger worries about the state of digital journalism today. More than 44% of respondents answered the write-in question, and most comments were notably detailed. They were also overwhelmingly negative. In their responses, which connected to the previous four research questions, journalists mentioned many online analytics they use to gauge the success of their paper’s digital strategies, including page views, unique visits, clicks, likes, and digital subscriptions. Through a textual analysis of the (n = 230) responses to this open-ended question, we uncovered five distinct themes about which the journalists were concerned: The journalists worried that their paper’s profit models aren’t working, the print product is still the top priority, the quantity of content is prioritized over its quality, digital strategies are changing too quickly, and staff sizes are too small to carry these strategies out effectively. Each of these themes touch on the organization level of the hierarchy of influences, and each is explored in detail below.

Lack of profit.

Unsurprisingly, one big worry the journalists expressed about their newspaper’s digital strategies was the fear that their papers aren’t profitable online and the people in charge of their online strategies don’t know how to become so. They expressed confusion and an overriding lack of faith in their paper’s abilities to forge a successful digital future. “Last year we far exceeded all our goals for clicks and page views, and yet it appears we lost money as a company,” one journalist said. “It suggests their business model isn’t working.” Others complained about the intrusion of analytics numbers in the newsroom, which might help journalists understand monetization of their content but also occasionally demoralize them. “I resist the idea of tailoring content toward fickle online audience that goes for clickbait,” said one respondent, who also mentioned that his staff receives “daily click counts [that] I sometimes find dismaying.

Many journalists fear that the industry might have focused too heavily on the web side of the business too soon, at the cost of ignoring the part of the business that continues to generate the most profit. “Business model is not working for most newspaper websites,” wrote one journalist. “Print still supports the digital side, even though there is very little recognition of this in most newsrooms.” Even those who didn’t express concern about monetization included it as a goal of their paper’s digital plans. “Our digital strategy is to develop content and apps that subscribers will pay for,” wrote one journalist. These thoughts were presented as fears, concerns and frustrations that directly impact the journalists’ job satisfaction.

Print is still king.

Another journalist described what he or she referred to as “The same problem seen everywhere,” or the fact that, “The print edition pays the rent, but its resources are ravaged to feed the digital future, with little financial return in the short and potentially long term.” In responses to this survey question, digital success was regularly compared to print success in terms of importance. “Our digital audience is increasing but not enough to offset print losses,” wrote another journalist. “And the quality of what we produce has declined dramatically, because of staff cuts, etc. and the nature of our online world, which is not always interested in quality writing and reporting.” This suggests that the print product is treated as more valuable than the online product, and that it is of higher quality—and that the two products are still different and have not been combined in journalists’ minds or in the production process. Another respondent commiserated with that perspective, albeit with a historic outlook: “I just think it’s hard to monetize that online traffic. It started with Craigslist gutting the classified ads that used to provide 40-60% of a newspaper’s revenue.”

Quantity over quality.

Other journalists feared that a newsroom focus on audience analytics data might distract the editorial staff from creating quality journalism or spread their time and priorities too thin to leave room to create it. “We are not catching up fast enough,” wrote one respondent. “We are still worried about clicks and page views (aka, #s) when we should really be pouring resources into producing journalism that is actual journalism, impacting readers.” The use of the phrase “actual journalism” might imply that some online journalism that gets clicks and page views does not adhere to the standards of print journalism. A focus on digital growth could also mean expanding a paper’s online audience to the national level and moving past a strictly local readership, worried one journalist. “We get readers through search engines who are not engaged or loyal to our brand,” worried one respondent. This fear suggests a concern about the long-term identity of the newspaper, and whether it will shift if its readers shift. Some people viewed technology as a potential curse for the industry:

I think we [are] unwitting participants in our own demise. We’ve outsourced our digital distribution to Facebook and Twitter rather than spending the energy on creating an environment that people might consider a destination, i.e., a website they feel compelled to navigate to and where they know they will find curated content.

Too much change.

Respondents also complained about “sometimes incoherent and always ever-changing” goals that fluctuate according to a paper’s finances. The more these goals change, the more journalists claimed to lose faith in them. To these journalists, even with a digital strategy, it’s “not clear that it either produces better journalism or that it creates more subscribers,” said one respondent. “The focus on how to best seize upon digital opportunities seems to change from quarter to quarter, as though corporate leadership and digital strategists are trying to figure out something that really works,” wrote one respondent. “As such, there is a lack of consistency to the efforts over time.” This lack of consistency breeds concern and frustration in journalists who must adapt and adhere to shifting strategies. Many journalists shared a similar hope for a sort of “magic bullet” solution that would make digital journalism profitable in one fell swoop. In the meantime, there’s a great deal of experimentation. “Who knows the way forward?” asked one journalist. “We’re certainly trying.”

Another journalist was more pessimistic:

I try not to think too big picture in my job. It’ll give me a headache. I can feel the newspaper industry collapsing. And those in charge don’t seem to convey confidence that whatever new model they’re implementing at the time is working.

Even disseminating a digital strategy within the newsroom poses challenges. “It’s not ‘public’ enough within the newsroom,” one journalist said of his or her newspaper’s strategy. “We’ve had a lot of system changes lately and are now part of a corporate arrangement, so we should ‘re-declare’ our newspaper’s online strategy so everyone is on board and knows how to proceed.”

Lack of resources.

Resource concerns were also common, as journalists worried that their newsrooms don’t have enough staff members to produce good journalism or don’t have enough web support behind their editorial staffers. “Not enough money/resources expended on our digital strategy,” is how one journalist summed up issues in his or her newsroom. These concerns also include technology quality; journalists worried about poor websites, mobile products and app design and weren’t sure their newspapers had the technological skills to improve them. The journalists surveyed regularly situated their papers’ digital plans in the context of recent or upcoming product releases, indicating a clear tie between the quality of a paper’s digital technology and its potential to achieve digital success. “We are told another web redesign is around the corner,” said one respondent. “I’d like to think it will be an improvement, but I’ll believe it when I see it.”

Discussion

Although this survey didn’t directly ask journalists to describe their professional motivations, the factors they use in order to measure their own success can lead to understanding the goals they are motivated to achieve at the organization level of the hierarchy of influences. For newspaper journalists, both qualitative and quantitative measures of success are important considerations at the organizational level and in the way editors gauge the value of journalistic content, part of the routines level. Across the board, however, the most frequently used measure of success is the quality of the journalism, which speaks to the professionalism of the occupation and the institutional level of the hierarchy of influences. The results suggest that journalists use a wide variety of factors to understand the worth of the content they create, and those factors—including impact in the community, online metrics and recognition from peer journalists—span multiple levels of the hierarchy of influences as well.

The quality of the content remained the top consideration when journalists were asked to identify the priorities their editors and superiors use to assess their performance in the workplace, an indication that, in general, the newsrooms’ overall philosophies for both content and professional performance focus on the same highest-ranked goal. However, when asked to assess their newspaper’s digital strategies in an open-ended question, a number of journalists expressed concerns that those strategies prioritize the quantity of the content over its quality. This conflict in responses might represent a disagreement between the way digital strategies are envisioned at the organizational level and the way they are enacted at the individual and routines levels of the hierarchy. Further research could build on and clarify this conflict. At the same time, editors also use additional factors—again, both quantitative and qualitative—to measure the success of their staffers, including attention online and on social media and the amount of content journalists produce.

Digital performance metrics frequently influence the content that journalists create. This finding is consistent with existing literature indicating that digital metrics influence journalists during multiple stages of the writing process, such as editing (Hanusch, 2017) and determining follow-up and extended coverage of specific stories (Vu, 2014). Furthermore, this prevalence of digital performance metrics in journalists’ work routines is important to note because it can diminish the quality of their work due to less guidance and feedback from editors (Agarwal & Barthel, 2015) and increasing institutional pressure to create content that “gets more clicks” (Tandoc, 2014). Previous research positing those ideas find support in these journalists’ open-ended assessments of their paper’s digital strategies, in which they worry about the influence of audience data on editorial decision-making.

Those who identified as online-only journalists indicated they were more knowledgeable of their publication’s digital strategies than print-only or hybrid journalists. In fact, online journalists reported strong certainty in their understanding of digital strategy, while print journalists replied with consistently middle-range knowledge of digital strategy. This measure of knowledge aligns with each group’s belief that their digital strategy is working. Online reporters were more likely to believe in the success of their newspapers’ digital strategies. In fact, for journalists across all platforms, the more knowledgeable they are of a digital strategy, the more likely they are to believe it is working. This relates to previous literature that found a direct relationship between journalists’ attitudes toward digital feedback and their likelihood of integrating it into the work routines (Tandoc & Ferrucci, 2016).

Despite these results, journalists also expressed considerable fears and frustrations about their papers’ digital strategies and how those strategies speak to the realities of online journalism today. In particular, they worried that the print product is still their paper’s most important focus, and they feared that prioritizing the digital product doesn’t mesh with a financial state in which the print paper is still more profitable than the website. This concern is reflected in research by Chyi and Tenenboim (2017), which suggests that media outlets may have jumped the gun when it comes to the digital revolution and placed too much focus on the digital potential of a business that continues to owe much to print. The journalists also worried about the ways their audiences are shifting online and the amount of resources available to them as they attempt to follow their supervisors’ occasionally confusing and constantly changing digital strategies.

These results demonstrate a platform-based divide amongst journalists who may be working within the same organization. This division in the newsroom—where perceptions of digital strategy are split along print and online boundaries—could possibly result in fractured goals and ideologies for the news organizations at large. This fractured mindset is also reflected in journalists’ thoughts about their newspaper’s digital strategies, which are considered to be divorced from their plans for print; in many cases, the papers’ print and digital products were referred to as entirely distinct. There appears to be a need for editors and superiors to solidify expectations and content evaluations towards a more unified team of journalists striving to meet shared, well-articulated and well-documented goals.

Limitations

This research was intentionally limited to the study of newspaper journalists who represent the 49 of the top major newspapers in the United States. It does not include journalists who work at smaller newspapers or other types of media outlets, including magazines, radio, television and online-only publications, and the results cannot be applied outside the realm of newspaper journalism. However, these results can be used as a bridge toward further research as applied to journalists who work in other media, and the way those journalists think about their jobs and professional performances, as well as their publication’s digital strategies.

This research is also the result of a 10% sample of more than 5,000 journalists approached via an online survey. Future studies would benefit from a larger pool of participants, as well as different methods of research geared toward in-depth qualitative analysis. Because this study was conducted via a survey, the researchers were unable to delve into the motivations journalists tie to the measurements they use to understand their work or to produce any sample anecdotes of how each value or metric is applied in regular newsroom interactions. Furthermore, the results can only provide us with initial insights due to limited statistical significance. While this was addressed by comparing median and interquartile range, continuing study would benefit from the statistical strength inherent of a larger corpus. The results of this study cannot be used to understand journalistic strategies outside of mainstream newspapers or applied to the general population. Future research would benefit from in-depth interviews or ethnography to help scholars understand in greater detail how these factors interact in real-time scenarios and how they differ according to journalistic roles and responsibilities. Because this study only divided journalists into print, web and hybrid (both print and web) categories based on the platform for which they conduct the most work, it relied on those distinctions to understand the difference between strategic understanding and decision-making, rather than the types of tasks the journalists perform in the newsroom: writer, section editor, managing editor, freelancer, etc. These factors are all important to future research about the professional roles and mindsets of journalists in the digital age.

Future Research

This study focused on a number of commonly used means of gauging content, such as reception by peer journalists, impact on a community and performance online and on social media, as broad categories through which to understand how journalists and their editors perceive the value of content and the performance of individual journalists. However, future research would benefit from moving beyond those broad categories into more specific examples—moving from social media to a division between shares, likes and reactions; between Facebook and Twitter and other social media platforms; etc. For example, this survey grouped all audience analytics data into a larger “online metrics” category; in the future, scholars should seek to understand the extent to which journalists use a variety of different metrics—including page views, visits, ad impressions and time on site—to make the same and other decisions.

This would be particularly helpful in understanding whether journalists value audience-focused engagement metrics or financially motivated monetization metrics more highly in gauging the success of their journalism. What is the key performance indicator? And when it comes to those online metrics, is there a standard measure of success? A benchmark of 2,000 page views might mean wild success for a smaller outlet, while it could indicate an unreturned investment for a larger, more mainstream online publication. Future research could expand upon these results by examining virality, how it’s measured and what the average range of goals for digital success—measured via online metrics—is for different types of media outlets.

References

Agarwal, S. D., & Barthel, M. L. (2015). The friendly barbarians: Professional norms and work routines of online journalists in the United States. Journalism, 16(3), 376–391.

Allan, S. (2006). Online news: Journalism and the Internet. Maidenhead, UK: McGraw-Hill Education.

Anderson, C. W. (2011). Between creative and quantified audiences: Web metrics and changing patterns of newswork in local US newsrooms. Journalism, 12(5), 550-566.

Barthel, M. (2016, June 15). Newspapers: Fact sheet. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.journalism.org/2016/06/15/newspapers-fact-sheet/

Bivens, R. K. (2008). The Internet, mobile phones and blogging: How new media are transforming traditional journalism. Journalism Practice, 2(1), 113-129.

Boczkowski, P. J. (2015). The material turn in the study of journalism: Some hopeful and cautionary remarks from an early explorer. Journalism, 16(1), 65-68.

Bogart, L. (1981). Press and public: Who reads what, when, where, and why in American newspapers. Hillsdale, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates.

Breed, W. (1955). Social control in the newsroom: A functional analysis. Social Forces, 33(1), 326-335.

Bivens, R. K. (2008). The Internet, mobile phones and blogging: How new media are transforming traditional journalism. Journalism Practice, 2(1), 113-129.

Chyi, H. I., & Tenenboim, O. (2017). Reality check: Multiplatform newspaper readership in the United States, 2007–2015. Journalism Practice, 11(7), 798-819.

Clayman, S. E., & Reisner, A. (1998). Gatekeeping in action: Editorial conferences and assessments of newsworthiness. American Sociological Review, 178-199.

Dimmick, J., Chen, Y., & Li, Z. (2004). Competition between the Internet and traditional news media: The gratification-opportunities niche dimension. The Journal of Media Economics, 17(1), 19-33.

Epstein, E. J. (1973). News from nowhere: Television and the news. New York, NY: Random House.

Hanusch, F. (2017). Web analytics and the functional differentiation of journalism cultures: individual, organizational and platform-specific influences on newswork. Information, Communication & Society, 20(10), 1571-1586.

Karlsson, M. & Clerwall, C. (2013). Negotiating professional news judgment and “clicks”. NORDICOM Review, 34(2), 65-76.

Lacy, S. (2000). Commitment of financial resources as a measure of quality. In R.N. Picard (Ed.), Measuring Media Content, Quality, and Diversity: Approaches and Issues in Content Research (pp. 25-50). Turku, Finland: Media Group, Business and Research Development Centre, Turku School of Economics and Business Administration.

Lacy, S. & Rosenstiel, T. (2015) Defining and measuring quality journalism. Retrieved from http://mpii.rutgers.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/129/2015/04/Defining-and-Measuring-Quality-Journalism.pdf

Loosen, W., & Schmidt, J. H. (2012). (Re-) discovering the audience: The relationship between journalism and audience in networked digital media. Information, Communication & Society, 15(6), 867-887.

MacGregor, P. (2007). Tracking the online audience: Metric data start a subtle revolution. Journalism Studies, 8(2), 280-298.

O’Neill, D. & Harcup, T. (2009). News values and selectivity. In K. Wahl-Jorgensen & T. Hanitzsch (Eds.). Handbook of Journalism Studies (pp. 161–174). Hoboken, NJ: Routledge.

Ruggiero, T. E. (2000). Uses and gratifications theory in the 21st century. Mass Communication & Society, 3(1), 3-37.

Schultz, I. (2007). The journalistic gut feeling: Journalistic doxa, news habitus and orthodox news values. Journalism Practice, 1(2), 190-207.

Shoemaker, P. J. & Reese, S. D. (2013). Mediating the message in the 21st Century: A media sociology perspective. New York, NY: Routledge.

Shoemaker, P. J. & Vos, T. (2009). Gatekeeping theory. New York, NY: Routledge.

Singer, J. B. (2004). More than ink-stained wretches: The resocialization of print journalists in converged newsrooms. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 81(4), 838-856.

Sumpter, R. S. (2000). Daily newspaper editors’ audience construction routines: A case study. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 17(3), 334-346.

Tandoc, E. C. (2015). Why web analytics click. Journalism Studies, 16(6), 782-799.

Tandoc, E. C. (2014). Audiences, journalists, and forms of capital in the online journalistic field. Revista Română de Comunicare Şi Relaţii Publice, XVI (3), 23-33.

Tandoc, E. C., & Ferrucci, P. R. (2017, March). Giving in or giving up: What makes journalists use audience feedback in their news work? Computers in Human Behavior, 68, 149-156.

Vu, H. T. (2014). The online audience as gatekeeper: The influence of reader metrics on news editorial selection. Journalism, 15(8), 1094-1110.

Welbers, K., van Atteveldt, W., Kleinnijenhuis, J. & Ruigrok, N. (2016). News selection criteria in the digital age: Professional norms versus online audience metrics. Journalism, 17(8), 1037-1053.

Kelsey N. Whipple is a doctoral student at the School of Journalism at the University of Texas at Austin, where she holds the school’s first Dallas Morning News Graduate Fellowship for Journalism Innovation. Her research focuses on gender, gender identity and class in the media and the influence of technology on mass communication. Whipple received her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in journalism from the University of Missouri’s School of Journalism.

Before moving to Austin, Whipple worked for an alt-weekly newspaper company as its Editorial Digital Director. In this role, she oversaw audience development, social media, online publishing and other digital best practices for 11 alt-weeklies across the country. She has also worked as a long-form staff writer and led digital strategy at the local level as a web editor. At UT, she is an assistant instructor for Digital Storytelling Basics, helping students navigate the rapidly evolving world of online journalism.

Jeremy L. Shermak is a doctoral student in the School of Journalism and Moody College of Communication Doctoral Fellow at the University of Texas at Austin. He has nearly 20 years of professional experience as a college professor, media analyst, and journalist. He has taught at the collegiate level for 14 years. He spent eight years as an assistant professor of communications at Moraine Valley Community College near Chicago, teaching journalism and written communications. He was the student facilitator for the honors program, founder and advisor for the student podcasting network, and lead consultant in the revision and creation of the journalism curriculum.

Shermak also has practical media experience. He began as a general assignment/sports reporter and photographer at the Harbor Country News in New Buffalo, Michigan, before moving on to the same role for the South Bend Tribune in South Bend, Indiana. He later worked as a media relations analyst at comScore Networks, an Internet analytics agency, and then managing editor at market research firm Mintel International.

Shermak’s research interests include crisis communications, sports journalism and partisan media. He is currently studying partisan influence on weather forecasting as well as local news framing of climate change reports. His work has been published in the journal Digital Journalism.