Quieting the Commenters: The Spiral of Silence’s Persistent Effect on Online News Forums

By Hans K. Meyer and Burton Speakman

The Internet may help overcome the Spiral of Silence because posters can remain anonymous. Forum moderators could alleviate some concerns by imposing group norms, such as moderation, to ensure civility. Through a nationwide survey, this study focuses specifically on comments at the end of news stories to examine the impact journalists can have on the conversation. Despite online advantages, the study finds the spiral of silence persists, but journalists who noticeably moderate comments have an effect. The key to overcoming the spiral of silence is helping commenters feel part of a community with other forum participants.

Introduction

Only a small percentage of readers are willing to comment on news stories online (Chung & Nah, 2009; Larsson, 2011), but online comments represent one way a newsroom can fulfill its democratic mission. Online comments at the end of news stories can serve as a “forum for public criticism and compromise,” that Kovach and Rosenstiel (2004, p. 6) call one of the essential elements of journalism. They can also help a newroom increase engagement and build audience as legacy media’s audience is shrinking.

Newsrooms need to understand why people do not join conversations publically, and the Spiral of Silence may help. People are unwilling to comment publicly because they want to avoid the isolation their minority opinions can cause (Noelle-Neumann, 1993). A bandwagon effect occurs when one side of an issue is more aggressive and causes their opinion to surge in popularity (Noelle-Neumann, 1993). It does not matter if those who are more aggressive actually represent the majority of the population (Noelle-Neumann, 1993). Journalists will play an important role in applying the democractic principles of the Internet in order to decrease their readers’ fears.

This study examines what elements a journalist can control to help overcome the spiral of silence and ensure that comments at the end of news stories create the public forum Kovach and Rosenstiel (2004) envisioned. Through a nationwide survey (N = 1,007) of Internet users that specifically asks them whether they comment at the end of news stories, the study measures participants’ experience with the spiral of silence within these forums and then asks what, if anything, journalists can do to lessen its effects. It also looks at how some of online forum features, such as anonymity and civility, influence feelings of isolation and if news organizations’ actions such as requiring real names, registration, or enforcing civility through active moderation make a difference. Beyond the theory, the study also describes, in part, what is needed to overcome a fear of isolation and bring audiences into a community.

Literature Review

The climate of public opinion is based on who speaks (Noelle-Neumann, 1993). If one side voices its opinion loudly, the other side may assume it is in the minority and remain silent (Noelle-Neumann, 1993). People make decisions on how vocal they will be through guidance from their environment (Johnstone, 1974). Research has found that during group settings many people would conform to the majority, ignoring their personal perception (Jackson & Saltzstein, 1958).

The key driver is a fear of social isolation (Noelle-Neumann, 1993; Salmon & Oshagan, 1990; Shoemaker, Breen & Stamper, 2000). One of the key missions of community journalism is to bring people together (Lauterer, 2005). Journalism remains different from other forms of communication because it seeks to give people the information they need to be free and self-governing (Kovach & Rosenstiel, 2001), and encourages them to publicly comment to create compromise. Newspapers have always had ways for their audiences to talk back, usually through letters to the editor (Reader, 2005), but the Internet provides easier and more inclusive options. However, does the Spiral of Silence happen when the Web offers everyone a place to voice their opinion in relative safety? Furthermore, does a journalist’s role change in creating an inclusive forum when so few people comment on online news stories?

Spiral of Silence and the Internet

New media have forced scholars to re-evaluate theories that were created to explain issues within legacy media (Gearhart & Zhang, 2015). The Web has fundamentally changed how the public receives and interacts with information (Porten-Cheé & Eilders, 2015). Prior to the Internet, few opportunities existed for people to publicly state their opinions. Options such as calling a talk show or writing a letter to the editor carried the risk of offending, alienating, or angering people the commenter would see each day. Noelle-Neumann’s theory was based on the limited choices in mass communication and their ability to influence a perceived majority opinion (Schulz & Roessler, 2012). Online, however, users are often led to information that conforms to their beliefs because algorithms chose news by what a person has previously viewed (Schulz & Roessler, 2012). Users focus on these sites and may avoid commenting on more mainstream locations (De Koster & Houtman, 2008).

To avoid condemnation, people look for sites that cater to their ideas because they feel isolated in other locations, both off and online (De Koster & Houtman, 2008). It is possible that those believe they face stigmatization in the offline world will feel more comfortable in online communities, where sites represent a “virtual refuge” (De Koster & Houtman, 2008). Finding other comments that agree with one’s opinion increases the likelihood of commenting, while finding posts that are hostile to one’s beliefs decreases that possibility (Gearhart & Zhang, 2015). Users also ignore posts inconsistent with their beliefs (Gearhart & Zhang, 2015).

Interpersonal connections also influence involvement in social media activity (Nekmat, Gower, Gonzenbach & Flanagin, 2015). People are motivated by how close they are to the message; comments from friends or family have more influence than those from people they do not know (Nekmat, Gower, Gonzenbach & Flanagin, 2015).

On the other hand, Porten-Cheé and Eilders (2015) found that online dissonance actually made members of the public more likely to speak about a topic. Familiarity and comfort within the online environment was the key determination of their willingness to comment online (Porten-Cheé & Eilders, 2015). In a similar vein, people who consider an issue important are more likely to comment despite others’ opinions (Ho, Chen & Sim, 2013). However, the bulk of Spiral of Silence research suggests that having a minority opinion remains the key detriment to online participation (Schulz & Roessler, 2012). People remain less likely to comment online if they believe their opinion is in the minority even if they can be anonymous online (Nekmat & Gonzenbach, 2013; Yun & Park, 2011). Even those with opinions in the majority are not more motivated to comment (Nekmat & Gonzenbach, 2013).

Online activity tends to be more about expressing an opinion and less about tangible action (Nekmat et al., 2015). People understand the difference between online and offline commentary and react accordingly (Schulz & Roessler, 2012). What happens online is limited to a small number of people unless traditional media notices what is being said (Schulz & Roessler, 2012). In addition, the permanence of online comments may discourage people from interacting (Nekmat & Gonzenbach, 2013). In the online context, the definition of Spiral of Silence cannot be based simply on the fear of isolation, because the relative anonymity of the Internet makes isolation outside of an individual website unlikely. For the purposes of this paper, the Spiral of Silence exists when someone fears a negative reaction that makes them less likely to comment at the end of online news stories (De Koster & Houtman, 2008; Nekmat & Gonzenbach, 2013; Porten-Cheé & Eilders, 2015; Schulz & Roessler, 2012).

Building online communities through commenting

How frequently people hear opinions can also effect the Spiral of Silence, and journalists play a pivotal role in the opinion dissemination online (Crawley, 2007). The more frequently people hear opinions against their own, the less likely they are to state their views (Eveland & Shah, 2003). The effect compounds over time with fewer people willing to make comments that represent minority positions (Eveland & Shah, 2003). Journalists need to make sure that a diversity of opinions are publicized. “News organizations act as a sentry, not for the community as a whole but for the dominant group[s] of power and influence” (Crawley, 2007, p. 320).

This is even more of a challenge considering the number of people who comment on online newspaper stories remains low (Weber, 2014). More diversity occurs as journalists encourage participation, and often, the best way to do that is to get involved (Meyer & Carey, 2014). In addition, people participate more in online conversations if the issue is salient to a smaller area, such as a city or a region in which they are involved (Weber, 2014). Those who feel a sense of belonging to a community are also more willing to comment (Jo & Kim, 2003; Meyer & Carey, 2014; Shah, McLeod & Yoon, 2001).

Anonymity

The concept of online community, however, seems contrary to the Spiral of Silence in its traditional form. A strong community with a majority opinion could lead to more isolation for those who do not share that opinion. Anonymity can also be a detriment to community. It is hard to connect with someone without knowing her name. But Borton (2013) found anonymity is a precursor to commenting on stories online. More than 80% of engagement-themed comments were posted on media websites anonymously (Borton, 2013). Isolation should not be as much of concern to Web users whose identities are unknown (Yun & Park, 2011). Along the same lines, making people identify themselves through some registration system decreased the number of people who commented (Borton, 2013). On the contrary, after South Korea passed a law banning anonymous online comments, the number of comments decreased, but the number of participants did not (Cho & Kim, 2012).

Uncivil comments devolve into name-calling and involve contempt and derision for another person’s opinion (Santana, 2014; Coe, Kenski & Rains, 2014). When incivility becomes personal, particularly if it focuses on the traits of a person, the comments are less valuable to public discourse (Brooks & Geer, 2007). Online incivility influences how people think about and react to certain issues (Anderson, Brossard, Scheufele, Xenos, & Ladwig, 2014) because uncivil comments have a greater effect on a person’s perception of unfamiliar issues (Anderson et al., 2014). Anonymous commenters are much more likely to be uncivil (Santana, 2014).

These varying definitions of incivility paint an inconsistent picture of how often it occurs in online comments (Coe, Kenski & Rains, 2014; Papacharissi, 2004). Journalists themselves seem unconcerned because they say they read comments, but they rarely reply (Meyer & Carey, 2014; Stroud, Curry, Scacco & Muddiman, 2014). The easiest way to combat incivility is for journalists to get involved (Meyer & Carey, 2014; Stroud, Curry, Scacco & Muddiman, 2014).

In addition, incivility may not have the discourse killing consequences many researchers predict. Uncivil comments resulted in arguments between posters and more comments (Brooks & Geer, 2007). Anonymity allows more people to comment, including those who would otherwise be silenced, which is more relevant to free speech than reading a few uncivil comments (McCluskey & Hmielowski, 2012; Papacharissi, 2004; Reader, 2012).

Trust matters, credibility and commenting

Giving people the freedom to comment in the ways they want is also central to the trust news organizations are trying to establish with their audiences. Audiences judge newspapers on how connected to the community they are based on institutional reputation (Newhagen & Nass, 1989). Online people base their decision on content to determine credibility, not the medium itself (Flanagin & Metzger, 2000). Credibility for online readers will relate more to the publication, not any individual reporter (Newhagen & Nass, 1989).

In addition, the public tends to view media more favorably if they are familiar with it (Bucy, 2003; Flangin & Metzger, 2007). Readers are also more likely to engage in interactive functions, such as submitting a letter to the editor, or a news story tip, with a news organization they know well (Chung, 2008). This is not to say that individual reporters have no role in influencing the public’s willingness to comment on online news stories. Having personal knowledge of the reporter does add personal credibility that works in combination with institutional credibility (Newhagen & Nass, 1989). Journalists who interact with the audience generate a greater sense of community and make people more willing to comment (Jo & Kim, 2003).

Community and its impact on Spiral of Silence

Newspapers become indispensable when they relentlessly become part of the communities they serve (Lauterer, 2005). Community connection helps determine someone’s willingness to comment because trust and cooperation take time to build (Jo & Kim, 2003 p. 214). Psychological attachment to a community also increases involvement (McLeod et. al., 1996). Those who have stronger ties to a community are more likely to be involved in sharing their opinion online (Cuba & Hummon, 1993; Sampson, 1988).

Building community means spending time in it. Residential stability, i.e. time spent living in a community, is a significant factor in creating community attachment (Sampson, 1988; Scheufele, Shanahan & Kim, 2002; Shah, McLeod & Yoon, 2001). Local ties and social networks account for more than 17% of the variance in someone’s activity within the community (Scheufele, Shanahan & Kim, 2002). Those who have lived in the community longer are more likely to be knowledgeable about local issues, and knowledge impacts the willingness to comment (Scheufele, Shanahan & Kim, 2002). Any type of structural connection to the community seems to make people more likely to be involved and willing to share their opinion (McLeod et. al., 1996).

The Role of Journalists

Journalists wanting to increase participation have to weigh the contrasting notions of anonymity and responsibility, but this is not an old problem. In one form or another, journalism has always worked to maintain its standing within its communities through establishing credibility (Meyer, 1988). The main reason journalists give for not allowing anonymity is their hope that real names lead to more civil discussions. Some publications have even removed comment sections, particularly for controversial stories (Santana, 2016).

However, merely seeing that a site is moderated makes readers more willing to comment because reciprocity is a necessary component for the creation of vibrant online communities (Lewis, Holton & Coddington, 2014). Seeing this active presence was the key determination as well for the creation of a sense of virtual community (Meyer & Carey, 2014).

However, the effectiveness of a journalist’s moderation is limited if those who comment do not trust them (da Silva, 2015). Journalists may have a propensity to select comments based on their own editorial values, which could isolate some participants and reduce any feeling of community (Diakopoulos, 2015). However, overall consistent involvement from journalists does have the ability to create positive relationships and feeling of community involvement and thereby increase the possibility of commenting (Chung & Nah, 2009).

Race

Some aspects exist which journalists cannot control. Based on traditional Spiral of Silence considerations, demographic factors such as age, race, education, and income may also matter in terms of someone’s willingness to comment on newspaper stories online. In general minorities are not engaged because they have negative feelings toward the media (Hackett & Carroll, 2006). Awad’s (2011) study of the San Jose Mercury News showed that Latinos felt excluded from the publication because its reporters did not cover their community objectively.

Journalists who work to create engaged communities can mitigate racial effects. Community media, particularly publications aimed at minorities, are helping to create a more engaged and participatory culture (Deuze, 2006). Through computer technology community media can cultivate participation from minorities (Sabiescu, 2012). To be successful these efforts cannot be seen as coming from outside, but must be part of the minority community’s vision and goals (Sabiescu, 2012).

Age is also a factor journalists must confront. Older people are more confident in their opinions and more connected to their communities (Cuba & Hummon, 1993; Scheufele, Shanahan & Kim, 2002; Shah, McLeod & Yoon, 2001). Those who are younger are less likely to be civically engaged (Scheufele, Shanahan & Kim, 2002; Shah, McLeod & Yoon, 2001). Those who are older and have higher incomes tend to be more involved in their communities (Scheufele, Shanahan & Kim, 2002). Age also influences both issue awareness and attitude strength (Scheufele, Shanahan & Kim, 2002).

But age, like all demographic factors, does not always override the motivation to comment. Individuals who would normally self-censor are willing to speak out about issues they believe are more important (Hayes, Glynn & Shanahan, 2005). Inherent knowledge of issue, involvement level in online forums, and availability of similar opinions are better determinants than age (Nekmat & Gonzenbach, 2013). Those who are more educated are more likely to comment (Ho, Chen & Sim, 2013; Nekmat & Gonzenbach, 2013).

Income could reduce the willingness to comment (Noelle-Neumann, 1993). Both income and education are related to a person’s willingness to comment publically (Lasorsa, 1991). The poor are often excluded from communities, and their voices are ignored (Laderchi, Saith & Stewart, 2003). The larger the public, the more likely education, income, or race will be important to the Spiral of Silence (Noelle-Neumann, 1993).

Hypotheses and Research Question

Previous research presents a wealth of way to predicte a Spiral of Silence effect, but have also offered differing opinions on how these predictors apply to online communication. They also offer mixed findings on the role that journalists’ effort to overcome the fear of isolation have in the online realm. Therefore, the main research question this study seeks to answer is the following: What factors influence the Spiral of Silence as it relates to people’s willingness to comment on online newspaper stories?

The expectation is that a person’s motivation and sense of community will be a significant factor in their willingness to comment on online newspaper articles. Commenters are typically motivated to participate through a combination of social and interactive reasons (Springer, Engelmann & Pfaffinger, 2014). Speakman’s (2015) study indicated that motivational factors were more influential than demographics. Furthermore, Meyer and Carey (2014) found that creation of a virtual community online was the primary predictor for someone’s willingness to comment online. “Even when participants noticed that online comment forums are characterized by rude or poorly written comments, they were still more likely to participate if they felt a sense of virtual community,” (Meyer & Carey, 2014 p. 223). Therefore, the study explores the following hypothesis:

H1: A belief that commenting helps to create a sense of community will have a direct and positive effect on perceived Spiral of Silence.

Anonymity is important to consider in this study because anonymous comments are common. Creating a registration requirement might remove some uncivil comments, but the audience is unconcerned (Reader, 2012). Those who do not comment are often much more against registering on a site than those who do (Springer, Engelmann, & Pfaffinger, 2014). Audiences believe anonymity leads to more comments (Springer, Engelmann & Pfaffinger, 2014), and studies have suggested that eliminating anonymous commenting leads to fewer people willing to comment, (Borton, 2013; Reader, 2012). Therefore, the study explores the following hypothesis:

H2: Procedures to eliminate anonymous commenting will have a direct and negative effect on perceived Spiral of Silence.

This study also considers credibility to be a motivating factor. As Bucy (2003) noted, the public believes publications they are familiar with are more credible. Credibility to some degree is formed by social relationships (Metzger, Flanagin & Medders, 2010). Group thinking is also a factor if someone trusts a publication (Metzger, Flanagin & Medders, 2010). In a similar vein, social networks are significant for both institutional participation and participation in public forums (McLeod, Scheufele & Moy, 1999). Therefore, the study explores the following hypothesis:

H3: Whether someone considers a publication to be credible will have a direct and positive impact on perceived Spiral of Silence.

As people live in a community for a long time they develop an attachment to the area, and are more willing to be involved in within it (Jo & Kim, 2003; McLeod et. al., 1996). In addition, those who have resided within an area for an extended period of time are more likely to have social interactions developing a level of community attachment that would motive them to speak out when they consider an issue salient (Cuba & Hummon, 1993; Sampson, 1988; Scheufele, Shanahan, & Kim, 2002; Shah, McLeod & Yoon, 2001). Those with stronger ties to the community and who feel more connected to the community will be more motivated and more likely to make a public comment. Therefore, the study explores the following hypothesis:

H4: Residency will have a direct and positive influence on perceived Spiral of Silence.

The role of demographics in the perceived Spiral of Silence effect online remains debated. Any factor that makes someone feel separated or isolated such as income, education or race will reduce their willingness to publically comment on issues (Noelle-Neumann, 1993). However, Johnson and Kaye (2002) found that age, education, and income were not relevant if someone found online newspaper content credibile. Furthermore, demographic variables did not matter when Web reliance and motivational factors were more significant (Johnson & Kaye, 2002). Therefore, the study asks the following research question:

RQ1. Will demographic factors such as race, age, income, and education have an influence on perceived Spiral of Silence?

Method

Rather than looking at individual forums, the study relied on a nationwide panel to find a wide range of views. The researchers created an online survey administered byClearVoiceSurveys.com, which has more than 540,000 panelists across the United States. The researchers paid $4 for each response. The invitations began in November 2012 and were completed in less than week.

The panelists who are part of ClearVoiceSurveys.com represent a wide variety of ages, incomes, education levels and races. They generally respond at a 20% rate because they are given a small cash reward (between $1 and $3) for completing a survey. For this particular study, ClearVoice invited panelists to participate until the researchers had received more than 1,000 completed responses. The number of panelists who turned down the study was not reported, so a response rate is not available. The invitations to panel members were based on U.S. census proportions of men and women and race. More than 63% of respondents were Caucasian, while 13% identified as Black or African American. More than 16% identified as Hispanic or Latino while 5% identified as Asian. The number of panelists who turned down the invitation was not available. Panel studies have become the preeminent method for sampling large groups as telephone and mail surveys have become increasingly difficult to conduct and they have consistently been reliable in generating generalizable samples (Halaby, 2004).

In total, 500 men and 507 women responded. Ages ranged from 18 to 67 with a mean age of 38.7. Participants had lived in their current home from one to 42 years, with a mean of 15.1 years. Median income level was $25,000 to $50,000 annually (28% of the sample) while another 24% earned between $50,000 and $75,000. Roughly 16% of the sample reported annual yearly income at less than $25,000, while the same percentage reported making between $75,000 and $100,000. Another 16% had income levels higher than $100,000 annually.

Median education level was a college degree (32%), while 27% reported some college and 24% had a high school degree only. Roughly 14% reported having an advanced degree (Master’s, Ph.D. or J.D.).

The study asked participants to estimate how often they post comments at the end of news stories on a continuous scale of never (1) to very often (5). The mean score for participation was 2.72 with an SD of 1.20. The largest percentage of respondents (31%) said they sometimes posted while 26% posted rarely, 16% posted often, and 9% posted very often. More than 18% of respondents said they never posted comments at the end of news stories.

The main dependent variable for this study was a perceived Spiral of Silence effect, which the researchers operationalized through four questions that asked how likely participants were to respond with a comment if the story’s point of view conflicts with theirs, most of the other comments conflict with their point of view, they do not feel strongly about the topic the story addresses, and if other comments have taken an aggressive tone. These question factored together with a Cronbach’s alpha of .853. Tavakol and Dennick (2011) report that alpha values between .7 and .9 represent acceptable values for assesing whether separate variables work together to measure the same concept.

The key factors the literature suggests that affect spiral of silence are anonymity, civility, and the actions of moderators—in this case journalists—to make the conversation more open. The researchers operationalized anonymity in two ways: how important it was that participants used their real names, and what impact requiring participants to register and use real names to post comments have. These two measures correlated at .653 and were summed and averaged as one variable.

Journalists may also have an effect on a perceived spiral of silence if they maintain an active moderating presence in forums. The study asked if participants had noticed active moderation in a newspaper comments section and how important it was for them to see it.

To operationalize engagement, the study asked respondents to rate their level of agreement with how being able to comment at the end of news stories (1) gave them a more positive attitude toward the news organization, (2) helps them trust the organization more, (3) makes them believe the story a bit more, (4) suggests the news organization cares about its audience, and (5) makes them think about connection with other people in the community. All five questions were averaged into one variable with a Cronbach’s alpha of .898.

Finally, the study measured the impact of commenting on community by asking respondents if they are likely to comment at the end of the news story if (1) the news story contributes to a sense of community, (2) the person who wrote the story creates a sense of community, and (3) the organization behind the story helps create community. All three questions were averaged into one variable with a Cronbach’s alpha of .934.

Results

The goal of the study is to build a model describing the effects of the Spiral of Silence in an online forum. The study focused on the comments at the end of online news stories because journalism has a mandate to build community and journalists’ actions can lessen the effects of the Spiral of Silence.

H1 examined whether the feeling of community affected perceived Spiral of Silence. An ANOVA that transformed the self-reported Spiral of Silence variable into low, moderate, and high groups and compared each group’s mean score on commnity creation showed strong statististical significance (F = 362.01, df = 2, p < .01). Significant differences were found for each group: low SoS effects (n = 378, M = 2.55), moderate (n= 443, M = 3.42) and high (n = 199, M = 4.23) at the p < .01 level. H1 was supported because feelings that comments created community had a direct positive effect on perceived Spiral of Silence.

H2 hypothesized that procedures journalists take to eliminate anonymity have have a direct negative effect on perceived Spiral of Silence. To test this hypothesis, a one-way ANOVA using the SoS groups as the factor and procedures to eliminate anonymity as the DV was statistically significant (F = 235.06, df = 2, p < .01) across all groups, with low (n = 378, M = 2.015), moderate (n = 443, M = 2.93) and high (n = 199, M = 3.82) all significant at the p < .01 level. H2 was supported.

H3 examined whether participants reported allowing comments at the end of stories enchanced the crediblity of the story and the news organization. A one-way ANOVA using the SoS groups as the factor and credibility as the DV found statistical significance across all groups (F = 175.66, df = 2, p < .01), with low (n = 378, M = 3.0198), moderate (n = 443, M = 3.5350), and high (n = 199, M = 4.2186) all siginificant at the p < .01 level. H3 was supported.

H4 examined the effect of residenct on perceived Spiral of Silence, but an ANOVA using the SoS group as the factor and the number of years a person had lived in his or her home as the DV, failed to find statistical significance overall (F = 2.94, df = 2, p > .05). Mean scores failed to shed light on why H4 was not supported as the low (n = 371, M = 15.30) and moderate (n = 432, M = 15.80) group had almost identical mean scores, while the high group (n = 198, M = 12.96) reported they had lived in the area three years less.

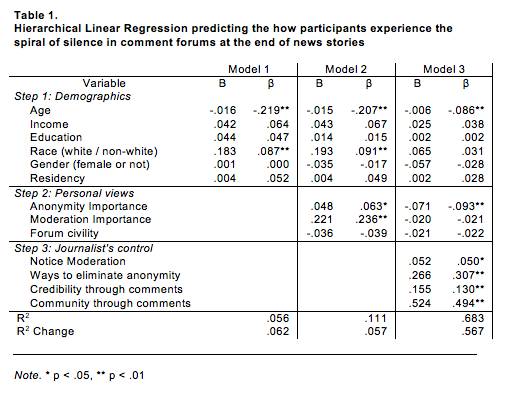

To determine the overall effect of community, anonymity, credibility and residency along with demographics, and the importance of and noticing moderation, the researchers built a hierarchical linear regression model to predict perceived Spiral of Silence. The first step contained demographic variables including age, education, income, race, gender, and residency, while the second represented the participants’ attitudes toward commenting. The final step contained all that a journalist can do to lessen the spiral of silence and encourage commenting, such as eliminate anonymity, create credibility and foster community.

The key predictors in this model, which accounted for more than 68% of the variance in perceived Spiral of Silence, and also mediated some of the effects of demographic and attitude issues in the first and second steps, were community, taking steps to eliminate anonymity, and credibility. Age remained a siginificant predictor in the final step while anonymity importance was a significant negative predictor. In other words, the more journalists sought to control the comment forum at the end of news stories through requiring registration, eliminating anonymity and enforcing community rules and credibility, the more perceived Spiral of Silence participants reported. This model suggests that to encourage people to overcome a fear of isolation, journalists do not necessarily need to be involved. In fact, the more likely people were to want comments to create community and enhance credibility, the more likely they were to report experiencing a spiral of silence effect.

The researchers created a second model with only the significant predictors to help determine what would encourage those who read news stories online to submit comments. Perceived Spiral of Silence was the first step, followed by attitudes and elements within a journalist’s control in the second step. The final step contained the two strongest predictors of perceived Spiral of Silence, community and credibility.

In a model that accounted for nearly 42% of the variance in how frequently someone said they contributed comments at the end of news stories, perceived Spiral of Silence was the key predictor accounting for 38% of the variance by itself. Efforts to mediate that made a difference were whether participants noticed moderation and what procedures the news organization took to eliminate anonymity. Credibility was not a significant predictor while community predicted only at the p < .05 level.

Discussion

Through a nationwide survey of online users with a specific focus on those who comment at the end of news stories, this study examined Spiral of Silence theory in the Internet age. Just as certain online features, such as the ability to comment anonymously and to easily connect with people all over the world, had the potential to lessen perceived spiral’s effects, the enforcement of group norms, such as requiring real names or actively maintaining a moderating presence, reinforced the isolation inherent in the theory. Overall, the study found direct positive effects for community, credibility and procedures to eliminate anonymity on perceived Spiral of Silence. In other words, as respondents feel more strongly that comments at the end of news stories exist to enhance a feeling of community, imbue news stories and organizations with credibilty, and that journalists need to take steps to remove anonymity, such as require real names or registration to post, they also experience stronger feelings of isolation from the site.

The model suggests several solutions for journalists interested in creating community online and the first might be the simplest. Young people report they experience less spiral of silence effects than older respondents, so journalists need to find ways to get them more involved. The online comment section could be the ideal place as young people are also more likely to be comfortable online. They need the guidance an involved journalist can offer.

The challenge with the model predicting reported Spiral of Silence is that it seems to put journalists in a no-win situation. If they want to lessen the effects of the spiral and encourage participation and meet their mandate to foster community and create a forum for public criticism and compromise, they need to loosen their control. They need to allow anonymity and look for those for whom crediblity and community are less important. This may mean, in fact, that the seemingly unrelated and unedited comments that many news stories receive are good ways to encourage people to join online conversations.

This model, it must be remembered predicted only the extent that respondents reported they experienced a Spiral of Silence effect. When predicting how frequently that respondents said they participated in comments at the end of news stories, community remained an important factor, although not as important as their reported Spiral of Silence. The strongest predictor in this model that added about 3% to the variance predicted was whether respondents noticed moderation in online news story comment forums. Respondents still had to overcome the fear of isolation the Spiral of Silence explains, but noticing a journalist supported them made a big difference, even when that journalist was taking steps to eliminate anonymity.

What this means for journalists is using comments at the end of their stories to overcoming fear of isolation and building forums for public criticism and compromise will not be easy. The first and easist step is having a noticeable presence in those forums. More journalists need to read they comments their stories receive (Meyer & Carey, 2014) and find positive ways to interact with commenters. They cannot make commenters feel like they are the ones responsible for giving the story with believability and meaning. Commenters should feel free to say what they want, within reason, whether it is directly related to the topic of the story or not.

This study also suggests that anonymity plays a somewhat contradictory role in perceived Spiral of Silence and a person’s willingness to post a comment at the end of a news story. The strong negative beta in the participation model suggests that the more important people find anonymity, the less frequently they post comments. However, the steps journalists take to eliminate anonymity were a strong positive predictor of participation, suggesting that those who comment the most frequently want to see people use real names and do not mind registering. When dealing with these two seemingly diametrically opposed views, journalists have to be careful. Their procedures to eliminate anonymity cannot seem to take anything away from those who value it. Clear but simple rules are needed, such as having to use a real name or a Facebook account, but journalists should not take these rules too far such as limiting the number of accounts a person can have or limiting the frequency with which she can comment.

This study suggests that some of the former determinants in the traditional definition of the Spiral of Silence have lost their impact. The length of time someone had lived in a commmunity was neither a predictor in the regression model or in a one-way ANOVA by itself. The Internet has fostered a worldwide community where the place one resides makes less difference than it once did. The nationwide, racially diverse panel the study used suggests that the effects of race and gender have decreased as well. The Internet has opened more opportunities for minorities and women to be heard. The ubiquity of the Internet, which most people now have in the palm of their hand through their smartphones, may have also overcome some of the effects of income and education.

The study is limited in its ability to examine specifics. While the nationwide sample the study used allowed it to tell a more comprehensive picture than studies that focused on a particular news site, it also presented some challenges with how respondents defined concepts. The researchers, for example, asked respondents to think about comments at the end of stories on a newspaper website but did not define the parameters any further. Respondents could consider biased forums, such as Daily Kos,Instapundit, or the Drudge Report, as newspaper sites. Those who visit sites like these typically have strong opinions they are willing to share. They also have a like-minded community in which to share them. These people could have experience less Spiral of Silence, but the researchers have no way of knowing.

Other definition challenges remain in the survey. All of the measures in the study are self reports. The researchers have no way of verifying, for example, how frequently respondents actually commented at the end of news sites. In fact, the percentages in this study seem higher than similar studies that focused on individual sites. Future research could take a case study approach, pairing this study’s nationwide sample, with specific examples and observations of news comment use in people’s homes. A content analysis of the comments themselves could suggest ways in which incivility is manifest, but it would be difficult to study those who do not comment that way. Other research could interview some of the survey respondents in depth to see more clearly what their motivations are for commenting and how the Spiral of Silence operates in an online enviroment.

Conclusion

Despite its limitations, this study makes a significant contribution to understanding the effects of the Spiral of Silence on online communities and on how journalists can use online communities to fulfill their mission to provide public forums. It adds nuance to the effect of anonymity and procedures to eliminate it, and suggests that anonymity may not be the best way to overcome Spiral of Silence effects. It underscores the need for journalists to get involved in comment forums and understand their audiences better to know when to push and when to back off in encouraging their participation. In the end, the study suggests that the Spiral of Silence persists in online comment forums. In fact, it may be an artifact of human nature that will always exist, no matter the communication platform or technology used. However, the Internet and journalists working with audiences online can make a difference in at least encouaging a few more people to overcome the isolation and participate in a forum for public criticism and compromise.

References

Anderson, A., Brossard, D., Scheufele, D., Xenos, M. & Ladwig, P. (2014). The “nasty effect:” Online incivility and risk perceptions of emerging technologies. Journal of Computer‐Mediated Communication, 19(3), 373-387.

Arpan, L. M. (2009). The effects of exemplification on perceptions of news credibility.Mass Communication & Society. 12(3), 249-270.

Awad, I. (2011). Latinas/os and the mainstream press: The exclusions of professional diversity. Journalism, 12(5), 515-532.

Borton, B. (2013). What can reader comments to news online contribute to engagement and interactivity? A quantitative approach. Retrieved from University of South Carolina Scholar Commons: http://scholarcommons.sc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3346&context=etd

Brooks, D. J. & Geer, J. (2007). Beyond negativity: The effects of incivility on the electorate. American Journal of Political Science, 51(1), 1-16.

Bucy, E. P. (2003). Media credibility reconsidered: Synergy effects between on-air and online news. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 88(2): 247-264.

Cho, D. & Kim, S. (2012). Empirical analysis of online anonymity and user behaviors: The impact of real name policy. Paper presented at the 45th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. 3041-3050.

Chung, D. S. (2008). Interactive features of online newspapers: Identifying patterns and predicting use of engaged readers. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13, 658-679

Chung, D. & Nah, S. (2009). The effects of interactive news presentation on perceived user satisfaction of online community newspapers. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 14, 855–874.

Coe, K., Kenski, K. & Rains, S. (2014). Online and uncivil? Patterns and determinants of incivility in newspaper website comments. Journal of Communication, 64(4), 658-679.

Crawley, C. (2007). Localized debates of agricultural biotechnology in community newspapers: A quantitative content analysis of media frames and sources. Science Communication, 28(3), 314-346.

Cuba, L. & Hummon, D. M. (1993). A place to call home: Identification with dwelling, community, and region. The Sociological Quarterly, 34(1): 111-131.

Dalisay, F. (2012). The spiral of silence and conflict avoidance: Examining antecedents of opinion expression concerning the U.S. military buildup in the Pacific island of Guam. Communication Quarterly, 60(4), 481-503.

da Silva, M. T. (2015). What do users have to say about online news comments? Readers’ accounts and expectations of public debate and online moderation: A case study.Participations Journal of Audience & Perception Studies, 12(2), 32-44.

De Koster, W. & Houtman, D. (2008). Stormfront is like a second home to me.Information, Communication & Society, 11(8), 1155-1176, doi:10.1080/13691180802266665

Deuze, M. (2006). Ethnic media, community media and participatory culture.Journalism, 7(3), 262-280.

Diakopoulos, N. (2015). Picking the NYT picks: Editorial criteria and automation. Editor’s Note. International Symposium on Online Journalism, 5(1) 147.

Eveland Jr., W. P. & Shah, D. V. (2003). The impact of individual and interpersonal factors on perceived news media bias. Political Psychology, 24(1), 101-117.

Flangin, A. J. & Metzger, M. J. (2000). Perceptions of Internet information credibility.Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 77(3): 515-540.

Flangin, A. J. & Metzger, M. J. (2007). The role of site features, user attributes, and information verification behaviors on the perceived credibility of Web-based information. New Media & Society, 9(2): 319-342.

Gearhart, S. & Zhang, W. (2015). “Was it something I said?” “No, it was something you posted!” A study of the Spiral of Silence theory in social media contexts. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 18(4), 208-213.

Hackett, R. & Carroll, W. (2006). Remaking media: The struggle to democratize public communication. CITY, STATE: Routledge.

Halaby, C. N. (2004). Panel models in sociological research: Theory into practice. Annual Review of Sociology, 30, 507–544. Retrieved fromhttp://www.jstor.org/stable/29737704

Hayes, A. F., Glynn, C.J. & Shanahan, J. (2005). Validating the willingness to self-censor scale: Individual differences in the effect of the climate of opinion on Opinion Express,International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 17(4), 443-455.

Ho, S. S., Chen, V. H. H. & Sim, C. C. (2013). The Spiral of Silence: Examining how cultural predispositions, news attention, and opinion congruency relate to opinion expression. Asian Journal of Communication, 23(2), 113-134.

Jackson, J. M. & Saltzstein, H. D. (1958). The effect of person-group relationships on conformity processes. The Journal Of Abnormal And Social Psychology, 57(1), 17-24.

Jeffres, L., Jian, G. & Atkin, D. (2009). Voicing complaints in the public arena. Ohio Communication Journal, 47, 97-112.

Jo, S. & Kim, Y. (2003). The effect of Web characteristics on relationship building.Journal of Public Relations Research, 15(3): 199-223.

Johnson, T. J. & Kaye, B. K. (2002). Webelievability: A path model examining how convenience and reliance predict online credibility. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 79(3): 619-642.

Johnstone, J. (1974). Social integration and mass media use among adolescents: A case study. In J. Blumler, & E. Katz (Eds.), The uses of mass communication (pp. 35-48). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Laderchi, C., Saith, R. & Stewart, F. (2003). Does it matter that we do not agree on the definition of poverty? A comparison of four approaches. Oxford Development Studies, 31(3), 243-274.

Larsson, A. (2011). Interactive to me—Interactive to you? A study of use and appreciation of interactivity on Swedish newspaper websites. New Media & Society, 13(7), 1180-1197.

Lasorsa, D. L. (1991). Political outspokenness: Factors working against the Spiral of Silence. Journalism Quarterly, 68(1/2), 131-140.

Lauterer, J. (2005). Community journalism, relentlessly local. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

Lee, H., Oshita, T., Oh, H. & Hove, T. (2014). When do people speak out? Integrating the Spiral of Silence and the Situational Theory of Problem Solving. Journal of Public Relations Research, 26(3), 185-199.

Lewis, S. C., Holton, A. E., & Coddington, M. (2014). Reciprocal journalism: A concept of mutual exchange between journalists and audiences. Journalism Practice, 8(2), 229-241.

Lin, C., & Salwen, M. (1997). Predicting the Spiral of Silence on a controversial public issue. Howard Journal of Communications, 8(1), 129-141.

McLeod, J. M., Daily, K., Guo, Z., Eveland, W. P., Bayer, J., Yang, S. & Wang, H. (1996). Community integration, local media use, and democratic processes. Communication Research, 23(2), 179-209.

McLeod, J. M., Scheufele, D.A., Moy, P. (1999). Community, communication, and participation: The role of mass media and interpersonal discussion in local political participation. Political Communication, 16(3): 315-336

McCluskey, M. & Hmielowski, J. (2012). Opinion expression during social conflict: Comparing online reader comments and letters to the editor. Journalism, 13(3), 303-319.

Metzger, M. J., Flanagin, A. J. & Medders, R. B. (2010). Social and heuristic approaches to credibility evaluation online. Journal of Communication, 60, 413-439.

Meyer, H. K. & Carey, M. C. (2014). In moderation: Examining how journalists’ attitudes toward online comments affect the creation of community. Journalism Practice, 8(2), 213-228.

Meyer, P. (1988). Defining and measuring credibility of newspapers: Developing an index. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 65(3), 567-574.

Nekmat, E. & Gonzenbach, W. J. (2013). Multiple opinion climates in online forums: Role of website source reference and within-forum opinion congruency. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly. 90(4), 736-756, doi: 10.1177/1077699013503162

Nekmat, E., Gower, K. K., Gonzenbach, W. J. & Flanagin, A. J. (2015). Source effects in the micro-mobilization of collective action via social media. Information, Communication & Society, 18(9), 1076-1091, doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2015.1018301

Newhagen, J. & Nass, C. (1989). Differential criteria for evaluating credibility of newspapers and TV news. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 66(2), 277.

Noelle-Neumann, E. (1993). The Spiral of Silence: Public opinion—Our social skin (Second ed.). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Papacharissi, Z. (2004). Democracy online: Civility, politeness, and the democratic potential of online political discussion groups. New Media & Society, 6(2), 259-283.

Porten-Cheé, P. & Eilders, C. (2015). Spiral of silence online: How online communication affects opinion climate perception and opinion expression regarding the climate change debate. Studies in Communication Sciences,15(1), 143-150.

Reader, B. (2005). An ethical “blind spot”: Problems of anonymous letters to the editor. Journal of Mass Media Ethics, 20(1), 62-76.

Reader, B. (2012). Free press vs. free speech? The rhetoric of “civility” in regard to anonymous online comments. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 89(3), 495-513.

Rose, M. & Baumgartner, F. (2013). Framing the poor: Media coverage and U.S. poverty policy, 1960-2008. The Policy Studies Journal, 41(1), 22-53.

Sabiescu, A. (2012). Exploiting the intergenerational connection in community media initiatives for minority cultures: A case study. The International Journal of Technology, Knowledge and Society, 7(6), 1-18.

Salmon, C. & Oshagan, H. (1990). Community size perceptions of majority opinion, and opinion expression. Public Relations Research Annual, 2(1-4), 157-171.

Sampson, R. J. (1988). Local friendship ties and community attachment in mass society: A multilevel systemic model. American Sociological Review, 53(5): 776-779.

Santana, A. (2014). Virtuous or vitriolic: The effect of anonymity on civility in online newspaper reader comment boards. Journalism Practice, 8(1), 18-33.

Santana, A. (2016). Controlling the conversation: The availability of commenting forums in online newspapers. Journalism Studies, 17(2), 141-158.

Scheufele, D. A., Shanahan, J., & Kim, S. H. (2002). Who cares about local politics? Media influences on local political involvement, issue awareness, and attitude strength.Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 79(2): 427-444.

Schulz, A. & Roessler, P. (2012). The Spiral of Silence and the Internet: Selection of online content and the perception of the public opinion climate in computer-mediated communication environments. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 24(3), 346-367.

Shah, D. V., McLeod, J. M. & Yoon, S. H. (2001). Communication, context, and community: An exploration of print, broadcast, and Internet influences.Communication Research, 28(4): 464-506.

Shoemaker, P., Breen, M. & Stamper, M. (2000). Fear of social isolation: Testing an assumption from the Spiral of Silence. Irish Communications Review, 8, 65-78.

Speakman, B. (2015). Interactivity and political communication: New media tools and their impact on public political communication. Journal of Media Critiques, 1(1): 131-144.

Springer, N., Engelmann, I. & Pfaffinger, C. (2015). User comments: Motives and inhibitors to write and read. Information, Communication & Society, 18(7): 798-815.

Stroud, N., Curry, A., Scacco, J. & Muddiman, A. (2014). Journalist involvement in comment sections. Retrieved February 10, 2016, from Engaging News Project:http://engagingnewsproject.org/research/journalist-involvement/

Tavakol, M. & Dennick, R. (2011). Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. International Journal of Medical Education, 2, 53–55. http://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.4dfb.8dfd

Weber, P. (2014). Discussions in the comments section: Factors influencing participation and interactivity in online newspaper readers’ comments. New Media & Society, 16(6): 941-957.

Yun, G. W. & Park, S. Y. (2011). Selective posting: Willingness to post a message online.Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 16, 201-227, doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2010.01533.x

Hans K. Meyer is an associate professor at the E. W. Scripps School of Journalism at Ohio University. His research focuses on how journalists adapt online to engage audiences and build community.

Burton Speakman is a Ph.D. candidate at the E.W. Scripps School of Journalism at Ohio University. His published research explores how user-generated content can influence public perception and credibility.