Six things you didn’t know about headline writing: Sensationalistic form in viral news content from traditional and digitally native news organizations

By Danielle K. Kilgo and Vinicio Sinta

From the listicle to the personalized headline, sensational form has become prevalent in online content. Interacting with online news articles through liking, sharing and commenting is one of the most popular social media forms of audience interactions with news organizations in modern times. Using a content analysis of viral Facebook news articles, this study examines the degree to which sensational forms appear in headline writing, including forward referencing, personalization, “soft” news structures and listicles. Findings suggest that while both types of organizations use these strategies, digitally native organizations are more likely to employ sensationalistic tactics in headlines while traditional organizations are more likely to appear in viral news for breaking stories. The discussion suggests that audience preference and expectation from specific news organizations may indicate content success.

Introduction

From the list of “6 things you must know” before doing a particular activity like water skiing or voting in the next election to the personalized headlines of today that beg youto read this, sensational form is paving the way for new content presentation, and driving engagement with online audiences. Headlines that use this type of language, ostensibly designed with virality in mind, are part of various news organizations’ strategies to reformat content for social media environments. Features like the use of forward referencing, personalization, and “listicle” structures are engaging, yet provoking, sensational strategies that entice readers to click, and then read online articles.

Enticement through headline writing and sensationalistic strategies is certainly nothing new, yet content structured through lists, personalization, and other sensational forms, are increasingly found among shared social media stories. For example, BuzzFeed has made a name for itself as the king of the viral “listicle” (Alpert, 2015), although list-form formats for texts are well established in our literary history. While some render BuzzFeed strategies “clickbait,” the company has vowed to take news and news distribution seriously, even if it means including tactics such as those mentioned previously. And, although all news organizations have not unanimously adopted these tactics, these pragmatic and structural devices are now more ubiquitous than ever. The purpose of this study is to determine the characteristics of viral news—news that has been evaluated highly by social media audiences, specifically those in Facebook.

The concept of sensationalism has been connected with appeals to audience emotion (Haskins, 1984), and sensational tactics and content have been useful in grabbing audiences’ attention. In the current digital and social media environment, news organizations and content providers are increasingly competing for attention and interaction with content from readers through social news sharing, liking and commenting. Content with the highest penetration and interaction numbers are often considered viral. However, the strategies for creating viral online content are volatile, and success depends on a number of considerations. Because sensationalism is coined as a tactic news organizations use to grab readers attention, this research explores the degree to which sensational tactics may appear in the most viral content within social media.

This article uses the overarching dynamics of journalism converged into a digital world to explore the audience preference to certain forms of sensationalism. Sensational form—the way things are written to exploit readers’ curiosity—has received less fierce criticism in the canon of academic scholarship that criticizes sensationalism. Despite the distaste for the industry, sensationalism has successfully captivated audiences’ attention, and many of the most prolific purveyors of “click-bait” and viral content are leaders of Web traffic and social media sharing in recent years (Cresci, 2014; Salmon, 2014; Sonderman, 2012). Thus, in digital environments and social media arenas, are these increasingly familiar sensationalistic forms rising to the top of the viral news pulpit? Are “traditional” and digitally native publications adopting these strategies, and do social media audiences welcome these practices?

We begin with a literature review of the state of online journalism and the emerging differences between digitally native and traditional organizations and their online presence, followed by a review of sensationalism and emerging sensational forms of news presentation. We then describe our methods and results of a content analysis of viral news from five traditional and two digitally native news organizations in 2014. Our research aims to discover the degree to which sensational form appears in viral news, and the characteristics of these strategies as they appear in online journalistic outlets.

The findings of this study help highlight the prevalence of these sensational forms, and their use by various types of news organizations in the most shared news content of specific news organizations in 2014. Additionally, this examination furthers conversations about the convergence of practices by traditional media organizations into digital spaces.

Participatory Journalism and Social News

Online news has revolutionized the amount of interactivity between audiences and media platforms. News content in the online sphere entices people to engage, redistribute, and discuss news, especially in social environments. Social media play important roles in influencing public participation with online news and thrives on constant interactive and engaging content (Antony & Thomas, 2010; Bennett, Breunig, & Givens, 2008; Boulianne, 2009; Nah, Veenstra, & Shah, 2006). Some news organizations maintain and adhere to traditional journalistic online practices (Deuze, 2003; Hermida & Thurman, 2008). However, many news organizations publish aggressively across media platforms, from online sites to social media to mobile applications (Bechmann, 2012; Wolf & Schnauber, 2014). Successful convergence of these practices to the digital realm requires adapting uses and methods to connect successfully with a wider target population (Domingo, Quandt, Heinonen, Paulussen, Singer, & Vujnovic, 2008; Klinenberg, 2005; Lawrence, Molyneux, Coddington, & Holton, 2013).

Online journalism often incorporates audiences through participatory content creation, engagement tactics, and networked distribution channels. While most online media offer new venues for interaction with readers, social media platforms have expanded the realms in which news organizations can engage and preserve audiences (Suau & Masip, 2013). This new digital area has left many traditional news organizations struggling to maintain their traditional norms and values. Despite the new dynamics of the digital world, traditional media outlets tend to continue to default to traditional journalistic standards (Deuze, 2003; Domingo et al., 2008; Hermida & Thurman, 2008). Studies reveal, for example, that offline content typically was shoveled online “as is,” with journalists failing to take full advantage of the Internet’s multi-way communication potential, instead using online platforms as merely another venue for dissemination. However, as digital news consumption has increased among audiences, these dynamics have changed.

Two types of news organizations have emerged as key players of online news distributors: the traditional news organization with an online presence, and the digitally native news site. For traditional news organizations, we specifically examine outlets that had established print or broadcast counterparts before embarking in the digital realm. The latter, digitally native news organizations, were not birthed from their print counterparts, but instead, existed, first, in the digital arena. The impacts and strategies of these organizations have been left relatively unexplored in academic research (Revers, 2014). Digitally native organizations have drafted new strategies for engaging audiences, challenging journalistic norms in the digital sphere, and conquering online interactivity with audiences. A recent Pew Research Center report (2015) revealed that digitally native organizations audience rankings surpass traditional media counterparts. Among the most successful cases are publications such as U.S.-based BuzzFeed and The Huffington Post, which have taken advantage of social media platforms to disperse their content and use social media analytics to evaluate their impacts. This participatory news distribution format has been disrupting the norms of the news media industry for the online world globally, with changes ranging from a broadening of the fundamental roles and functions of a “news organization” to changing the writing style.

The social aspects of communication are essential economically as well, with online-only publications relying, largely, on clicks and shares to equal revenue. Seen through a positive lens, the democratic potential of this digital participatory journalism—journalism that thrives on two-way communication with audiences—is an unprecedented and convenient venue for increasing public awareness and knowledge (Borger et al., 2012; Bowman & Willis, 2003).

However, not everyone is an optimist. “Since its inception, online journalism has been derided as a lower form of work than traditional journalism” (Barthel, Moon, & Mari, 2015, p. 13). Social media complicates these notions, especially as journalism has incorporated social media into news distribution and evaluation (Hermida & Thurman, 2008). On the more pessimistic side of this debate, scholars argue that the online sphere does not grant increased democratic potential (Hayes, Singer, & Ceppos, 2007). Borger et al. (2012) argued that contrary perspectives focus on the degradation of journalistic quality and journalistic norms, and the blurring lines of press objectives and press financial gain. Thus, the debate about online news and the sensational aspects that accompany it is ongoing in both the scholarly and professional realms.

In the virtually unlimited space offered in online platforms, most news outlets do not face the temporal and spatial constraints associated with traditional journalism, but instead, fight to catch and keep the readers’ attention. Social evaluation, whether through subscription, reader feedback, or viewership size, is an important part of the assessment process. At the same time, though the incentives that guide production are different for various media types, Web traffic, and advertising have become major considerations for the creation and distribution of content developed in multiple spheres, including print and broadcast journalism. The relative ease and immediacy of Web analytics enable newsrooms to respond to content, better tailor practice for their audiences, and adopt news digital skills (MacGregor, 2007). The audiences’ role in assessing this information through interaction in online spheres proves to be an even more vital component to the news production agenda.

Sharing and interacting with online content is an integral part of participatory journalism practices. For example, more than half of all online content consumers exchange information with others (Allsop, Bassett, & Hoskins 2007). In online environments, the audience plays a significant role in increasing the distribution capacity of news and establishing quality standards. On social media networks, this role is fulfilled by different interactions with content, including liking, sharing, and commenting on news items. To some degree, these interactions assess quality as well as virality within a social network. This journalist-audience interaction is pivotal in creating viral news.

Berger and Milkman (2012) evaluated content characteristics of viral news, operationalizing viral news as articles that were most-shared from The New York Times’website. The analysis showed that news stories with more emotional content (i.e. vocabulary), and with a positive tone were more likely to shared through e-mail. Today, this operationalization is limiting, especially because news sharing becomes a more prevalent practice in social networks than through e-mails. The present study, however, uses total interaction numbers (and for this study, these numbers come from the leading social media platform Facebook) to assess the characteristics of viral content. Using the combination of multiple types of interactions (commenting, sharing, liking) we are better able to assign a quantitative value, at the very least, of the number of times people interacted with information within this platform suggesting the potential for virality in one dominating social network.

Sensationalism

To some extent, the negative perceptions of participatory journalism can be associated with similar arguments and negative perceptions of sensationalism. Sensationalism has been ambiguously defined for years. The term’s general classification refers to the narrative, less structured, news stories that do not fit into the typical “hard” news genre.

However, the evaluation of sensationalism is best understood by Haskins (1984) who refers to sensationalism as evoking curiosity—albeit he believes this curiosity is morbid. The morbidity of sensationalism is rather an evaluation than a characteristic of the term, and ultimately, the evaluation of sensationalism creates a debate about the concept. At one end, scholars view sensationalism as a model for showing decency by exploiting the extreme (Stevens, 1985). At the other end, journalism critics have held harsh sentiments toward sensationalism, regarding it as a contributor to a news “sewer,” degrading and dumbing down the minds of readers everywhere (Adams, 1978; Bernstein 1992; Slattery & Hakanen, 1994). In these instances, sensationalism is akin to the stories found in tabloids, and at the core of their arguments is the content, not the structure. By removing the evaluation, and focusing directly on the notion that sensationalism is a form that evokes curiosity, we can examine this term as a more legitimate strategy in emerging journalism practices. Thus, this research builds off of Haskins’ (1984) assertion that sensationalism uses tactics that evoke curiosity.

The increased prevalence of sensationalistic journalism in the digital realm intentionally seeks to engage audiences through simplistic, attractive content that drives audience emotion or peaks interest. In an explication of sensationalism, Grabe and colleagues (2001) argued that the concept deals with both form and content. Regarding content, sensational stories are described as focused on celebrities, crime, and social taboo (Davie & Lee, 1995; Shaw & Slater, 1985). Form is identified by the techniques—writing and visual—that help present stories in a sensational way. Specifically, we look at particular stylistic and curiosity-evoking forms and article structures in which sensationalism might thrive: soft news structures, personalization, forward referencing and listicles.

“Hard” and “soft” news. “Hard” and “soft” news articles tend to address vastly different new values. Soft news stories have been considered simplistically as the counter to all news that is not considered “hard.” Soft news includes stories deviating from the news formats typical before the pre-1980 advent of cable/satellite network and Internet presentation of news (Baum, 2002). At the core of soft news are tactics identified with sensationalism: shock, intrigue, and curiosity. According to Patterson (2000), soft news articles are centered on human-interest stories and sensationalistic features. Additionally, soft news articles are structured in a way that leads to more narrative styles of writing, a form much less rigid than breaking news stories. Hard news stories typically include breaking events, invoke values of timeliness and importance, and adhere to the inverted pyramid design, and thus are less likely to include sensational topics.

Forward referencing. Blom and Hansen (2015) argued that many headlines include the linguistic facets of forward referencing. Forward referencing is the “reference of forthcoming (parts of the) discourse relative to the current location in the discourse” (Blom & Hansen, 2015, p. 87). This strategy identifies an object without first giving it a definition, using pronouns and demonstrative adjectives instead, leaving the actual subject as a mystery. This form is substantively different to the traditional journalistic headline which typically identifies the “who” or “what” central to the news story. For example, a headline that reads, “Listen carefully. This is what rape culture sounds in America” does not define what “this” is—and therefore evokes curiosity through form. These tactics use a form of provoking reader interest by introducing information gaps that entice to click on the headline. Examples of forward-referencing illustrate the variety of ways in which users can generate curiosity and suspense, tempting some readers to continue reading to find out information that would have traditionally been already available in a more traditional headline. In their study of Danish publications, Blom and Hansen (2015) found forward-referencing techniques present in about 17.2% of articles. The authors’ measures of forward-referencing were adapted in this study, and were used to examine the presence in viral media.

Personalization. Another potential curiosity-driving element of sensationalism is personalization: news that addresses the reader directly. Mateson (2004) argues that outlets such as The Guardian created weblogs that bridge gaps with the reader by building interpersonal relations. One way in this interpersonal relationship thrives is though an inclusive and explicit use of personal pronouns. Lauerbach (2009) contends that this personalization of information is an intentional effort to connect with audiences on an intimate level. Additionally, imperative sentences that have understood subjects are forms of personalized headline writing. We argue that this strategy also evokes curiosity in readers by identifying personally with the reader, and could also be considered a form of sensationalism. Personalization creates an invitation for audiences to not only read, but also engage on a personal level—not a traditional value of news.

Listicle structure. Published in 1989, “The 7 habits of highly effective people” is still a widely popular book—its shelf life extending well into its second decade as a best seller. Revered for its clear and concise yet moving content, the text is perhaps a prime example of the editorial markets’ “viral” listicle—or arrangement of information in a list article (or book). Headlines for listicles typically begin with a cardinal number and organize information in the form of a list. While BuzzFeed is often credited as the king of the listicle in the online news sphere (Alpert, 2015; Cresci, 2014), the inclusion of this type of content in news outlets has grown in recent years.

Listicles are also derided for their role as part of a trend of degradation in content quality. In a listicle article itself, Poole (2013) discussed whether listicles were the first steps to unraveling the “very fabric of written culture.” Still, the listicle has also been hailed for its simplification of information, and its ability to be read in nonlinear form, despite the apparent negativity it garners from critics, and to some extent, news organizations have produced content using this structure (Alpert, 2015). Information in listicles is organized into a concrete number of items: 7 habits, 10 things, 11 ways. Listicles entice the reader provide a useful structure for a seemingly comprehensive analysis of an issue with brevity.

Research Questions and Hypotheses

The overall question guiding this study is the degree to which news audiences in social media environments interacted with content that was structured sensationally. We examine each sensational form—soft news, forward referencing, personalization and listicles—as indicators of the degree to which sensational form might contribute to overall virality. We then examine each form for their presence in digitally native and traditional publications as indicators of possible deviation in audiences’ preferences for news structure.

RQ1: To what extent do hard and soft news appear in viral headlines?

RQ2: How do hard and soft news strategies appear differently in viral news between traditional and online native publications?

RQ3: To what extent does personalization appear in viral headlines?

RQ4: How do personalized strategies appear differently in viral news between traditional and digitally native news organizations?

RQ5: To what extent do listicles appear in viral headlines?

RQ6: How do listicles appear differently in viral news between traditional and digitally native news organizations?

RQ7: To what extent does forward referencing appear in viral headlines?

For the concept of forward referencing we can hypothesize possible news organization preferences by advancing Blom and Hansen’s (2015) work which showed that forward-referencing is more often used in soft news than in hard news, and in tabloid and commercial news organizations than traditional outlets.

H1: Forward referencing is more likely to appear in soft news stories.

H2: Forward referencing is more likely to appear in digitally native publications.

Methodology

To answer the research questions and test the hypotheses presented above, we conducted a content analysis of content and structural characteristics of online headlines from seven news organizations.

Data and sampling. A subscription was purchased from NewsWhip, a media analytics data company that catalogs social media interactivity on content of more than 100,000 news organizations, including the degree to which individual articles are shared, “liked,” and commented social media platforms (NewsWhip’s Social Publisher Rankings – Methodology, 2014). The subscription allowed the researchers access to download content from a set list of news organization tracked by Newswhip. Ultimately, seven media companies were purposefully selected for the study. Five of these are “legacy” media—news organizations that were prominent before the advent of online media and that continue to be known primarily for their offline products: newspapers The New York Times and The Guardian and television networks CNN, Fox, and the BBC. The other two media organizations included in the sample are “online-native” content providers based in the United States: The Huffington Post and BuzzFeed.

We identified potential viral or highly valued news articles by isolating the top 600 most viral stories news stories with the highest sum of social media interactions on Facebook (total number of comments, shares and likes) for the year 2014 from all seven publications. While we acknowledge other social media platforms are can be critical players in spreading viral news, we isolate Facebook because it is the largest social network in the world, and because social media platforms each have distinctive cultures and audiences, and thus what is viral on one network may not be viral within another. Articles averaged about 39,000 total marked interactions (M = 39004.1, SD = 68576.1). After eliminating three duplicate entries we were left with 597 items for coding: 55.3 percent from digitally native publications (n = 330) and 44.7 percent from traditional publications (n = 267). The number of items coded from each individual news outlet is as follows: The Huffington Post (n = 154); BuzzFeed (n = 156); Fox (n = 102); CNN (n = 40); The New York Times (n = 50); BBC (n = 32); and The Guardian (n = 43).

Coding. Coding featured the following variables: source, hard news/soft news, personalization, forward referencing and listicles. After three rounds of testing and refining the aforementioned measurements, coders, all authors of this paper, ran inter-coder reliability tests with a series of items that account for slightly under 10% of the total sample (n = 50). Cohen’s kappa was used to calculate inter-coder reliability between two coders, both authors of this study (Neuendorf, 2002). The results of this ICR test were satisfactory according to Poindexter and McCombs (2000), with reliability coefficients ranging from kappas of .73 to 1. Individual kappa scores are reported with descriptions of each variable.

Source. NewsWhip data included the domain URL under which each news item was posted, as well as the date of publication. We further used the URL domains to categorize news items as traditional media (NYT, Guardian, Fox, CNN, BBC) anddigitally native (Huffington Post, BuzzFeed) (k = 1).

Hard/Soft News. Each news item was coded based on whether the news story corresponded to “hard” news stories (i.e. breaking news, public affairs reporting) or “soft” news stories, which in this case anything from non-time sensitive feature stories to quizzes and tests (k = .91).

Personalization. Headlines were coded for wording that addresses (or involves) the reader directly: these could include second-person pronouns (the use of “you” or an inclusive “we”), or, alternatively, the use of first-person (“I”, or a non-inclusive “we”). Example: “Foodini’ machine lets you print edible burgers, pizza, chocolate” (CNN); “Reading on a screen before bed might be killing you” (The Huffington Post). Additionally, imperative statements, or statements that request or command information that do not include “you” in the subject but instead imply “you” in the subject, were included as a personalization or intent to specifically address the reader (k = .88).

Forward referencing. Headlines were coded for the inclusion of words that allude to events or newsmakers that require reading the full article for understanding. Coders identified only situations were demonstrative pronouns such as “this”; “what”; and “why” were used before a declaration of the identifier in a headline. Some examples are: “Why most Americans oppose gun control” (Fox News); “This is what happens to your body when you’re embarrassed” (BuzzFeed) (k = .73).

Listicles. A third structural recurrent among the most viral articles in the sample was the use of lists and countdowns. These pieces, coined listicles, usually have headlines that describe the category of the listed items, as well as the total number. Listicle features are not mutually exclusive with forward referencing and personalization. Examples: “21 classic NYC spots that closed forever in 2014” (BuzzFeed); “25 of the best clubs in Europe, chosen by the experts” (The Guardian) (k = 1).

Data Analysis. Descriptive statistics and chi-square analysis were run to answer most variables in this study. RQ1 and RQ2 asked the degree to which hard and soft news appears in viral headlines and this appearance variation by news organization types. Frequencies were used to identify the extent of content variations, and chi-square tests were run to understand variations in news publications. RQ3 through RQ6 asked the extent to which personalization and listicles appeared in viral headlines and their differences by news organization type. Descriptive statistics and chi-square analysis were used to answer these questions. RQ7 asked the degree to which forward referencing appeared, and was answered using descriptive statistics. H1 (Forward-referencing is more likely to appear in soft news stories) and H2 (Forward-referencing is more likely to appear in digitally native publications) were both answered using chi-squared analysis.

Results

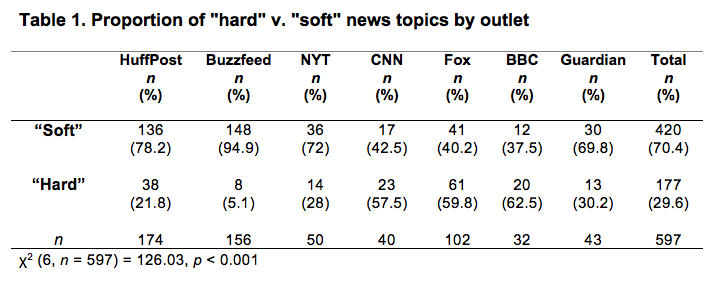

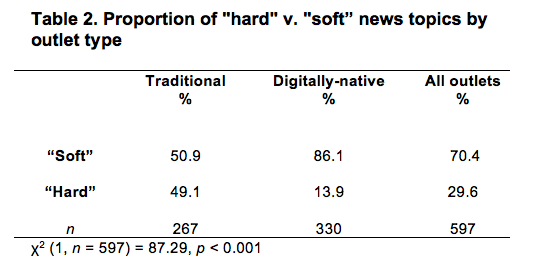

The first research question asks about the (RQ1) prevalence of “hard” versus “soft” news in viral headlines from 2014, and (RQ2) how their proportion varies according to the type of media outlet. The results of our content analysis showed 70.4% were “soft” news, while only 29.6% were “hard”, or breaking news.

As for the prevalence of both types of news stories in traditional and digitally-native news sites, Tables 1 and 2 show that the two digitally native outlets had the highest proportion of “soft news” while traditional media sites were more likely to have “hard news” within their viral articles, χ2 (1, n = 597) = 87.29, p < 0.001.

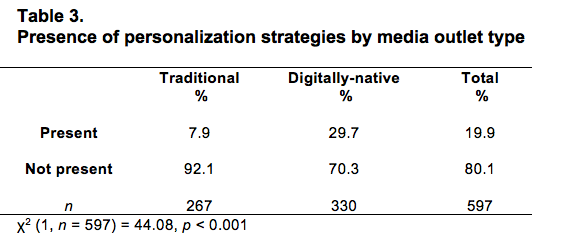

The remaining research questions and hypotheses deal with the structure of the headlines and their prevalence in different types of news stories. RQ3 asks about the prevalence of personalization in the most viral headlines from 2014. According to the analysis, 119 headlines, amounting to 19.9% of the sampled items, contained first or second person pronouns, writing from the perspective of the author(s) or addressing the reader. The breakdown by type of media outlet (RQ4), presented in Table 3, shows that the digitally native sites were statistically more likely to use these strategies, χ2 (1,n = 597) = 44.08, p < 0.001.

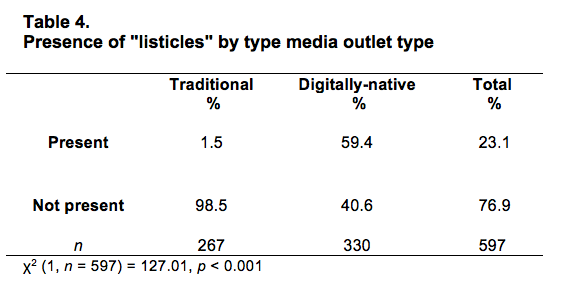

RQ5 deals with the pervasiveness of “listicles” among the most viral items posted in 2014. Analysis revealed that 138 stories (23.1% of the sample) were presented in the listicle format. As the breakdown by outlet on Table 4 shows, almost all of the highly viral items using a list-like structure were published by digitally-native outletsBuzzFeed and The Huffington Post, χ2 (1, n = 597) = 127.01, p < 0.001 (RQ6).

RQ7 addresses the prevalence of forward referencing strategies, such as the use of indicative pronouns or adjectives, or the deliberate introduction of information gaps in headlines. According to the results of the content analysis, 43 headlines, amounting to 7.2% of the sample included at least one feature of forward referencing. Among these, the most common strategy was the use of This, either as a demonstrative adjective or as a pronoun, and was found in 20 headlines, or 3.4% of the sample. Less common were the use of What (2.2%), Why (1.7%) or personal pronouns (0.5%).

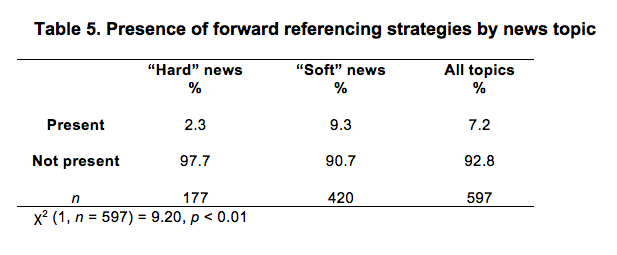

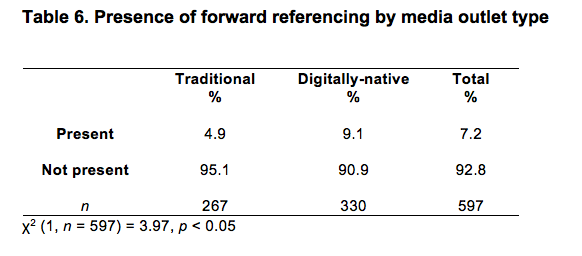

H1 predicts that forward referencing is more likely to appear in soft news than hard news. A chi-square test (presented in Table 5) supports the hypothesis—”soft” news were statistically more likely to feature forward referencing than breaking news or public affairs reporting, χ2 (1, n = 597) = 9.20, p > 0.01. These crosstabs show that only four hard news stories (2.3%) successfully employed forward referencing.

In a similar vein, H2 postulates digitally native content providers would be significantly more prone to use forward referencing. This hypothesis was also supported by a chi-square test (shown in Table 4), although the observed effect is not as strong, χ2 (1, n = 597) = 3.94, p > 0.05. As noted in RQ2, only 43 stories overall included forward referencing, 30 of which appeared in digitally native organizations and 13 that appeared in traditional publications.

Discussion

Social media has opened the doors to expansive modes of two-way communication between media organizations and audiences. These interactions have led to wider scopes of information distribution to hard-to-reach audiences, and allow news organizations to have audience assessment of material. Scholarship that focuses on the digital realm seeks to answer questions such as: What do audiences share with their peers? How do they interact with content? In this context, we see sensationalism is one tactic that has helped foster connections with the public since the rise of “Yellow Journalism,” even though the ethical foundations and implications of the concept remain in question.

In this study, we sought to understand how frequently sensational forms appear in viral online content and what types of organizations are more likely to employ these tactics. Our findings revealed that among the most viral news stories, those published by digitally native organizations are more likely to feature sensationalistic forms. While legacy organizations have a significant presence in viral content and utilize sensational tactics to engage audiences, these strategies appear less frequently in their viral content in comparison to online native organizations. The possible use differences may be partially accredited to the varying business models of digitally native and traditional organizations. While traditional organizations have established offline revenue sources—such as subscription and broadcast advertising—digitally native organization compete with both the traditional organization and other online content providers. Thus, the attention-grabbing sensational practices may be more reliable for them to gather much-needed traffic, which often a significant part of their business models.

A prominent form of sensational from in viral news items is the listicle. Listicles accounted for about one-quarter of viral content in this study, and online native organizations successfully use the tactic most often. However, the appearance of this form in most viral content supports claims that online and mobile news consumers are perhaps most likely to engage in a “news snacking”—that is easy-to-read, concise formats (Lawor, 2013). Listicles also offer a commercial advantage for news organizations. For example, listicles that require the reader to click on multiple pages will generate more impressions for a page. It is not surprising then that almost half ofBuzzFeed’s most viral headlines are listicles, and the organization is the leader in sensational news among the sample in this study.

However, in light of BuzzFeed’s more recent declarations to produce credible news, it appears that mass Facebook audiences prefer their former content. This finding brings into question BuzzFeed’s future potential to act as a key player in online news distribution. How has, or will, this organization find balance and credibility in the continued production of what appears to be their standard, sensational and viral content while producing more hard-setting news for the masses? If BuzzFeed is, in fact, providing more standard news, we speculate there are different economic incentives for doing such than those of their entertainment content.

Overall, viral news articles are mainly soft news; hard news and breaking news formats were a minority of the viral content put out by online news outlets. Therefore, we surmise that the highest social activity on Facebook is less about being the first to “break” news though the temporal nature of breaking news may indeed be a factor in some situations. Instead, viral news production is about disseminating content that is relatable and narratively written. This observation is important for news management companies who are continually adopting strategies to engage publics within this particular network.

In terms of a global distribution strategy for news content, the personalized, narratively written and soft news formats are more likely to be shared in a more expansive way than hard news. We do not make the assertion that hard news is any less important, and certainly has its place in social media networks. However, for journalists aiming to expand their reach to national or global levels, sensational approaches examined in this study may be more successful for articles with less temporal immediacy. An important limitation of this study is that these viral tactics are not necessarily valid in other social media networks. Future studies should examine cross-network virality and the variations in content from with high levels of audience interactions in additional platforms such as Twitter, Tumblr, and Instagram.

Our findings also illustrate that readers may choose to interact with content from traditional news organizations for different reasons than digitally native organizations. Among traditional media, most viral stories were breaking, hard news—indicating audiences continue to turn to them to share that type of immediate information, instead of digitally news organizations. In spite of the great popularity that sites likeBuzzFeed and The Huffington Post currently enjoy, legacy media still command higher levels of trust (Pew Research Center, 2014), and thus this may account for the content variations found in this study. Additionally, this finding indicates that sheer evaluation of news quality and effectiveness should not be limited to social media interactions and possibility of viral news.

On the other end of the spectrum, audiences may prefer to share information from digitally native organizations that are more narratively based. Similarly, it is also possible that legacy media companies, such as The New York Times, choose social media agendas at the beginning of the day, and like Lee, Lewis and Powers (2014) suggest, these agendas primarily consist of hard news topics. Therefore, if traditional organizations have not succeeded in employing these sensational form tactics in the past, it is possible they do not appear in this sample because journalists and editors are aware of the audience’s preferences for breaking news.

This study also discovered that about 20% of the content with the most Facebook activity featured personalization strategies in their headline. Though social media dynamics are constantly changing, in 2014, audiences’ responded to personalized, but generalizable, approaches to news storytelling. These strategies, again, were significantly more prevalent in content from digitally native media than in the sites of legacy news outlets. However, when examining the output of individual media organizations, we were able to identify that among traditional media The Guardian is particularly more open to using personalization strategies, with personalized headlines appearing in 16.3% of their viral headlines.

Forward referencing was present in viral media only about 7.3% of the time. While this form of writing may indeed be significant in achieving curiosity, its prevalence in highly viral stories is minimal—less than even so than forward referencing strategies found in 2013-2014 coverage of Danish publications by Blom and Hansen (2015), which included a more significant 17%. While this study does not attempt to predict the extent of the use of forward referencing, it appears that in the United States this is an emerging tactic that entices audiences to be interested in or engage with content in social media arenas.

The observations from this content analysis place online native organizations as perhaps the best at creating viral content; BuzzFeed and The Huffington Post alone make up more than half of the sample of widely shared stories. However, the forms of sensationalism that online native organizations use are not present near as often in traditional media, leaving extensive room for further exploration. If these structural elements are most prevalent in digitally native organization viral headlines, what specific characteristics of traditional media produce viral news aside from breaking news? Future studies should examine the content of viral news—such as topics and news values—which could potentially provide more insight for commonalities in viral news. Still, these findings reveal that online journalism outlets can still utilize sensational forms as an opportunity for engaging wider audiences.

By identifying form variances in viral content, this study highlights the degree to which some forms of sensationalism are observable in the most viral media. This study only accounts for a partial description of viral content. We urge future researchers to look into the sensationalism from a contextual standpoint (i.e. news value and news topic) within viral media to see if patterns can be established. This is particularly the case for traditional media organizations, which appear to either employ these tactics less often, or to have less success with audiences interacting with sensationally structured content. Future studies should further explore the interplay between subject matter, form and the predetermined trust that audiences have in particular media outlets, which might provide further insights into what makes people engage with, and share online news contents.

We were able to identify that approximately half of viral news incorporated some sensationalistic writing tactic in the headline. However, this finding does not necessarily support the idea that online journalism brings with itself a degradation of traditional journalism values as critics of sensationalism presume (Barthel, Moon, & Mari, 2015). Instead, by looking at the most viral content, we speculate that sensationalistic form should be viewed as a packaging element, and considered a useful tool for distributing information in a highly competitive social environment. For example, a BuzzFeed headline that reads “16 important tips every iPhone 6 owner should know” includes useful, technology information for readers and up-to-date information about issues owners may encounter with the iPhone 6. This article is not aligned with negative evaluations of sensationalism, despite its presentation in a sensationalist way. Therefore, while sensational form is indeed prevalent among viral content, this does not necessarily equate a decline in journalistic standards. Instead, our study finds that prevailing headline writing tactics are useful in encouraging audiences to engage with content, through liking, sharing and commenting on social media.

Future studies should consider further the relationship between form and contextual intricacies of viral news, exploring how tone and emotion drive audience engagement with certain content. Additionally, it would be important to advance this exploratory study by considering other posting tactics that might drive virality, such as the inclusion and framing of visuals included with the social media postings, as well as other collateral texts that accompany headlines.

Conclusion

Ultimately, journalism and storytelling are not “antithetical activities” (Tuchman, 1976, p. 96). Our findings suggest that using these curiosity-building types of sensationalistic form are effectively part of what makes some content viral. While sensationalism offers a gamut of responses from scholars about the good and bad aspects of its form and content expectations, its tactics make people share, engage people through “liking” and commenting, and ultimately help distribute information to broader audiences. This study finds that employing sensational presentation tactics such as personalized headlines and narrative structures might be beneficial to reaching more general audiences because they tend to be shared more often.

Traditional media organizations have been less successful at employing or less inclined to use these tactics, as viral headlines from these organizations are less likely to include the sensational forms of personalization, forward referencing, listicles, and soft news. It is possible that legacy news organizations, which developed their craft before the advent of social media, are just more prone to maintain and adhere to traditional journalistic practices in online environments (Deuze 2003; Hermida & Thurman, 2008).

As the legitimacy of sensationalism forms are negotiated, and journalistic organizations attempt to validate their principles and practices, the media empires struggling to connect with audiences online may find increased engagement with minor modifications of content and structure, improving two-way communication and fostering the much-desired model of the Internet as a sphere for informed deliberation.

References

Adams, W. C. (1978). Local public affairs content of TV news. Journalism Quarterly, 55(4), 690-695.

Allsop, D. T., Bassett, B. R., & Hoskins, J. A. (2007). Word-of-mouth research: Principles and applications. Journal of Advertising Research, 47(4), 388-411.

Alpert, L. I. (2015, January 29). BuzzFeed nails the “listicle”; What happens next? The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from http://www.wsj.com/articles/buzzfeed-nails-the-listicle-what-happens-next-1422556723

Antony, M. G., & Thomas, R. J. (2010). “This is citizen journalism at its finest”: YouTube and the public sphere in the Oscar Grant shooting incident. New Media & Society. 12: 1280–1296.

Barthel, M. L., Moon, R., & Mari, W. (2015). Who retweets whom? How digital and legacy journalists interact on Twitter. Tow Center for Digital Journalism. New York, New York. Retrieved from: http://towcenter.org/research/who-retweets-whom-how-digital-and-legacy-journalists-interact-on-twitter/

Baum, M. A. (2002). Sex, lies, and war: How soft news brings foreign policy to the inattentive public. The American Political Science Review, 96(1), 91-109.

Bechmann, A. (2012). Towards cross-platform value creation: Four patterns of circulation and control. Information, Communication & Society, 15(6), 888-908.

Bennett, W. L., Breunig, C., & Givens, T. (2008). Communication and political mobilization: Digital media and the organization of anti-Iraq war demonstrations in the US. Political Communication, 25(3), 269-289.

Berger, J., & Milkman, K. L. (2012). What makes online content viral? Journal of Marketing Research, 49(2), 192-205.

Bernstein, C. (1992, June). The idiot culture: Reflections of post-Watergate journalism.The New Republic, 22.

Blom, J. N., & Hansen, K. R. (2015). Click bait: Forward-reference as lure in online news headlines. Journal of Pragmatics, 76, 87-100.

Borger, M., van Hoof, A., Costera Meijer, I., & Sanders, J. (2012). Constructing participatory journalism as a scholarly object. Digital Journalism, 1(1), 117–134.http://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2012.740267

Boulianne, S. (2009). Does Internet use affect engagement? A meta-analysis of research. Political Communication, 26(2), 193-211.

Bowman, S., & Willis, C. (2003). We media. How audiences are shaping the future of news and information. The Media Center at the American Press Institute. Reston, VA. Retrieved from: http://www.hypergene.net/wemedia/download/we_media.pdf

Cresci, E. (2014, August 11). 21 things you need to know about BuzzFeed’s success. The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/media/2014/aug/11/21-things-you-need-to-know-about-buzzfeeds-success

Davie, W. R., & Lee, J. S. (1995). Sex, violence, and consonance/differentiation: An analysis of local TV news values. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 72(1), 128-138.

Deuze, M. (2003). The Web and its journalisms: Considering the consequences of different types of news media online. New Media & Society, 5(2), 203-230.

Domingo, D., Quandt, T., Heinonen, A., Paulussen, S., Singer, J. B., & Vujnovic, M. (2008). Participatory journalism practices in the media and beyond: An international comparative study of initiatives in online newspapers. Journalism Practice, 2(3), 326-342.

Grabe, M. E., Zhou, S., & Barnett, B. (2001). Explicating sensationalism in television news: Content and the bells and whistles of form. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 45(4), 635-655.

Hayes, A. S., Singer, J. B., & Ceppos, J. (2007). Shifting roles, enduring values: The credible journalist in a digital age. Journal of Mass Media Ethics, 22(4), 262-279.

Haskins, J. B. (1984). Morbid curiosity and the mass media: A synergistic relationship. InMorbid curiosity and the mass media: Proceedings of a symposium (pp. 1-44). University of Tennessee/Gannett Foundation.

Hermida, A., & Thurman, N. (2008). A clash of cultures: The integration of user-generated content within professional journalistic frameworks at British newspaper websites. Journalism Practice, 2(3), 343-356.

Klinenberg, E. (2005). Convergence: News production in a digital age. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 597(1), 48-64.

Lauerbach, G. (2009). Audience design in national and international news: The case of BBC and CNN. Language in Life, and a Life in Language: Jacob Mey–A Festschrift, 267-275.

Lawor, A. (2013, August 12). 5 ways the listicle is changing journalism. The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/media-network/media-network-blog/2013/aug/12/5-ways-listicle-changing-journalism

Lawrence, R. G., Molyneux, L., Coddington, M., & Holton, A. (2014). Tweeting conventions: Political journalists’ use of Twitter to cover the 2012 presidential campaign. Journalism Studies, 15(6), 789-806.

Lee, A. M., Lewis, S. C., & Powers, M. (2014). Audience clicks and news placement: A study of time-lagged influence in online journalism. Communication Research, 41(4), 505-530.

MacGregor, P. (2007). Tracking the Online Audience. Journalism Studies, 8(2), 280-298.

Matheson, D. (2004). Weblogs and the epistemology of the news: Some trends in online journalism. New Media & Society, 6(4), 443-468.

NewsWhip’s social publisher rankings-Methodology. (2014). NewsWhip. Retrieved fromhttp://blog.newswhip.com/index.php/2014/07/ultimate-guide-newswhips-social-publishers-rankings.

Nah, S., Veenstra, A. S., & Shah, D. V. (2006). The Internet and anti-war activism: A case study of information, expression, and action. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(1), 230-247.

Patterson, T. E. (2000). Doing well and doing good: How soft news and critical journalism are shrinking the news audience and weakening democracy-and what news outlets can do about it. Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University.

Pew Research Center (2014). Political polarization and media habits. Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center. Retrieved fromhttp://www.journalism.org/2014/10/21/political-polarization-media-habits/

Pew Research Center (2015). State of the News Media 2015. Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.journalism.org/2015/04/29/state-of-the-news-media-2015/

Poindexter, P. M., & McCombs, M. E. (2000). Research in mass communication: A practical guide. Boston, MA: Bedford St. Martin’s.

Poole, S. (2013). Top nine things you need to know about ‘listicles’. The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/nov/12/listicles-articles-written-lists-steven-poole

Revers, M. (2014). The twitterization of news making: Transparency and journalistic professionalism. Journal of Communication, 64(5), 806-826.

Salmon, F. (2014). Viral math [Blog post]. Reuters-Analysis and opinion. Retrieved fromhttp://blogs.reuters.com/felix-salmon/2014/02/02/viral-math/

Shaw, D. L., & Slater, J. W. (1985). In the eye of the beholder? Sensationalism in American press news, 1820-1860. Journalism History, 12(3-4), 86-91.

Slattery, K. L., & Hakanen, E. A. (1994). Sensationalism versus public affairs content of local TV news: Pennsylvania revisited. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 38(2), 205-216.

Sonderman, J. (2012, October 23). Huffington Post leads news sites with the most viral stories on Facebook. Poynter. Retrieved fromhttp://www.poynter.org/news/mediawire/192652/huffington-post-leads-news-sites-with-the-most-viral-stories-on-facebook/

Stevens, J. D. (1985). Sensationalism in perspective. Journalism History, 12(3-4), 78-79.

Suau, J., & Masip, P. (2013). Exploring participatory journalism in Mediterranean countries. Journalism Practice, 8(6), 670–687.http://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2013.865964

Tuchman, G. (1976). Telling stories. Journal of Communication, 26(4), 93–97.

Wolf, C., & Schnauber, A. (2015). News consumption in the mobile era: The role of mobile devices and traditional journalism’s content within the user’s information repertoire. Digital Journalism, 3(5), 759-776.

Danielle K. Kilgo is a doctoral candidate in the School of Journalism at The University of Texas at Austin. Her research interests include political and visual communication.

Vinicio Sinta is a doctoral student in the School of Journalism at The University of Texas at Austin. His research centers on ethnic-oriented news media, with a focus on U.S. Latinos/as.