Toward Omnipresent Journalism: A Case Study of the Real-Time Coverage of the San Antonio Spurs 2014 NBA Championship Game

By Zhaoxi (Josie) Liu

Based on a field study, this paper examines how the San Antonio Express News practiced omnipresent journalism in its coverage of the Spurs’ NBA 2014 championship game. This study refines the concept of omnipresent journalism as having two dimensions: time (real-time coverage) and space (on multiple platforms); and consisting of three rounds of news presentation: live tweets, real-time website updates and print paper. Such omnipresent journalism primes mobile journalism and requires journalists to be proficient in multitasking while prioritizing their tasks. Meanwhile, in the omnipresent news environment, journalists have perceived the print newspaper as the holy grail of quality journalism. Journalists also need to brace themselves for glitches, technological and otherwise.

Introduction

This article presents a case study of the multi-platform, real-time coverage of the San Antonio Spurs’ 2014 NBA championship game by the San Antonio Express News(hereafter the Express News), examining how the coverage strived toward omnipresence, in both temporal and spatial senses, through three rounds of news presentation: live tweets first, then website real-time updates, and finally, print.

The study focuses on the operation of the metro reporters as they went around the city to cover fan reactions on game night, rather than the coverage of the game per se by sports reporters. Using ethnographic methods, this study provides a close look at the operation from behind the scenes and assesses its broader implications for journalism.

Case studies have been widely carried out by journalism scholars for its advantage in providing in-depth examination with a clear focus, hence the chance to investigate real-world examples in a nuanced manner and providing insights that may not otherwise obtainable (Robinson, 2009b). There have been, for example, case studies of news coverage of Hurricane Katrina (Robinson, 2009a) and the murder of a police officer and the ensuing manhunt (Marcionni, 2013), live tweeting of the presidential primary debate (Heim, 2015), and the operation of a particular news organization (Robinson, 2009b).

The study presented here focuses on the news coverage of one event by one news outlet and has its limitations—a short time period and limited news material. However, the Spurs game was not just another event. In San Antonio, a possible win of the NBA title by the Spurs on their home court generates enormous local interest and is one of the biggest and most important event coverage the Express News undertakes. It is a major journalistic operation and a chance to observe and study such an operation from the inside is scarce. In addition, this operation embodies the key aspects of news production routines in the newsroom and therefore the analysis transcends just one particular event. From day to day, many other stories, from the breaking news of a crime to the local celebration of July 4, are covered more or less the same way: following the three rounds of presentation (discussed in detail later) and striving to be omnipresent. Understanding how such a major event is covered using digital tools and platforms, therefore, provides valuable insight into the new trends of journalism practice.

This case study, from just one news organization, may not explain what happens at other news originations. Nevertheless, through dissecting the process of covering one major event, it endeavors to address some broader implications for journalism in the age of social media, mobile phones and distributed content.

The Newspaper Industry’s Struggle and Omnipresent Journalism

It is no longer news that the newspaper industry is struggling to stay alive and the possible disappearance of the print newspaper all together has been speculated for some time (Brock, 2013; Westlund, 2013). The number of daily newspapers, as well as their circulation, has been on steady decline in recent decades. There were 1,878 daily newspapers in the United States in 1940, and that number dropped to 1,331 in 2014. Total daily circulation peaked in 1984 at more than 63 million and dropped to just 40 million in 2014; Sunday circulation follows the same trajectory (National Newspaper Association, 2015). In the 1940s, over one-third of Americans received a daily newspaper. By the end of the first decade of the 21st century, readership was down by about half to less than 15% of the population (Kamarck & Gabriele, 2015).

Declining readership goes hand-in-hand with decline in advertisement revenue, and the economic recession in 2008 exacerbated the situation. In 2007, newspapers in the United States made around $42 billion in print advertisement revenue, and in 2014, the number dropped to around $16 billion. Even though newspapers have started to make profit from their digital products, the increase in digital advertisement revenue—$3.2 billion in 2007 and slightly up to $3.5 billion in 2014—is almost trivial comparing with the loss of print advertisement revenue (Barthel, 2015). The economic hardship of the industry also led to the downsizing of the journalism workforce. In 2007, there were 52,600 full-time newsroom employees in newspapers. Two years later, 20% of those jobs were gone and the lost jobs may never return despite the recovery of the economy (Jurkowitz, 2014). According to the American Society for Newspaper Editors, total newsroom employment dropped to 32,900 by 2015 (Kamarck & Gabriele, 2015).

In 2014, the newspaper industry faced yet another major change in readership: 39 of the top 50 digital news websites, including some newspaper websites, have more traffic to their sites and associated applications coming from mobile devices than from desktop computers, prompting a Pew Research Center report to declare, “Call it a mobile majority” (Mitchel, 2015, para. 1). Meanwhile, more and more Web and mobile users are getting their news from social media such as Facebook (Mitchel, 2015). In short, the changing news consumption habits, mostly driven by the fast-evolving mobile devices and social media, demand constant adjustment and adaptation of newspapers and other news organizations.

The rhetoric of the moribund newspaper notwithstanding, there are still over 1,000 newspapers in circulation in the United States and they are still striving to survive, even thrive (National Newspaper Association, 2015). In the past eight or nine years, for instance, newspapers have rushed to create mobile applications in an attempt to gain a foothold on the home screen of the mobile phones (Westlund, 2013). A 2011 survey revealed that 62% of daily newspapers with circulations above 25,000 had a mobile app. A majority of those without a mobile app planned to develop one within a year (Jenner, 2012). Today, very few newspapers, if any, do not have a mobile app. The Express Newsand mysa.com (the Express News’s free website) each has its own mobile app.

To survive the digital age, one strategy newspapers have tried to adopt is to become omnipresent, being available on as many different platforms as possible, as discussed by Westlund (2013). Beside such spatial presence, this study adds a temporal dimension to further enhance the concept of omnipresent journalism—the kind of journalism that presents news in real time, as well as on multiple platforms: print, website, social media, mobile apps, etc. Taking into account the temporal dimension is particularly relevant to journalism as timing is a crucial component of news. In other words, the concept of omnipresent journalism discussed in this study is located in the meta-perspective of the survival of the newspaper industry, as omnipresent journalism can be regarded as the industry’s response to various crises it is facing. This concept indicates the industry’s constant adaptation to ever changing technologies and ways of conducting journalism, and its search for a future.

The word “omnipresent” has been used in journalism to describe the pervasive presence of news in today’s society (Purcell, Rainie, Mitchell, Rosenstiel, & Olmstead, 2010). The theoretical contribution of this study lies in its advancement of “omnipresent journalism” as a scholarly concept, including both temporal and spatial dimensions and useful in assessing and explaining a new trend in journalism practice. As a scholarly concept, “omnipresent journalism” is rather new, but the phenomena that inspire the concept have existed for some time. Robinson (2011), for example, has studied journalism as a process in a mobile obsessed and social media saturated environment, comprised of a fluid, on-going productive process as opposed to producing just a finite print product. She depicts the entire day-to-day operation in the newsroom as an “authorship uncertain and work forever unfinished” process, due to the involvement of the audience through online comments and the need to produce news for multiple platforms using multiple technologies. The coverage of the Spurs game was also a multi-author, multi-platform, multi-product process. However, this study stresses that the process of covering the game is not just for producing a product; it is the product. Such a shift is a distinct feature of journalism in an age of mobile devices and social media.

As demonstrated through the coverage of the Spurs game, the entire process of the coverage was presented to an audience through live tweets and constant website updates. What the audience consumed, from what they saw on their mobile phones, computers or other devices on the game night, to the print newspaper they read the next morning, was no longer a finite news product, but a process. It is not just journalism as or in process; it is journalism of process, involving multiple platforms, multiple types of journalistic product, multiple tools/devices, and multiple deadlines. And such a process, this study argues, is omnipresent in both temporal and spatial dimensions and therefore embodies the practice of omnipresent journalism.

To better understand such omnipresent journalism, this study explores the following questions:

RQ1: How did the Express News practice omnipresent journalism in its coverage of the Spurs championship game, both in terms of time and space?

RQ2: What are such omnipresent journalism’s implications for journalism in a broader sense?

Methodology

The San Antonio Express News is the only daily newspaper serving the San Antonio area. A Hearst newspaper, the Express News has a daily paid circulation of about 100,000 and 200,000 on Sunday (print and digital combined). The newsroom employs more than 140 reporters and editors. In the week ending December 6, 2015, the newspaper’s website, http://www.mysanantonio.com, had 11.8 million page views and 1 million unique visitors, which is a good snapshot of the site’s traffic. The annual page-view total in 2015 was over 500 million, based on figures provided by the newspaper. Content on mysa.com is free, but the newspaper has another, fee-based website, called the premium website: www.expressnews.com, launched in 2013 (Heckman, 2013). The focus of the current study is the free website because it is the main website that carried the real-time coverage of the Spurs’ 2014 triumph.

The main method for this study is ethnographic field research that involves observation and interviews. Ethnographic studies of news organizations have contributed to the field of journalism studies several classic works, covering different aspects of news production, from productions routines, news values to professional ideologies (Fishman, 1980; Gans, 1979; Gitlin, 1980; Tuchman, 1978). These works provide evidence of the methodological strengths of field research in studying journalists and their practices. Through its close contact with the field and people in the field, such studies can provide rich insights into the nature of news production and characteristics of practitioners, allowing studying them from the inside (Mabweazara, 2013; Paterson, 2008). The methods are open to contingencies and unexpected situations emerging in the field, and therefore are flexible in data collection, which allows more nuanced understanding of the subject (Berkowitz, 1989; Cottle, 2007). Such flexibility is particularly useful in investigating current developments in journalism as the newsrooms are experiencing fast and complex transformations on a daily basis (Mabweazara, 2013).

The findings of the current study are based on three kinds of data: field notes, interviews, and documents. Field notes were taken during an eight-week field study, in June and July of 2014, in the newsroom (mostly the Metro Desk) to explore journalists’ use of Twitter in news coverage. Realizing that the coverage of the Spurs game was a prominent example of using Twitter, the researcher followed the process of the coverage, from pre-coverage meetings to the aftermath. The researcher also accompanied a reporter to a sports bar and observed her work during the entire game.

Eight weeks are not a very long period for field research, but adequate for gathering ethnographical data for the question at hand. The first half of the field study was devoted to observing journalists’ use of Twitter and the second half to interviews. The research was designed as such in order to have a data set that includes journalists’ practices and their own reflections of the practices (Atkinson & Coffey, 2003; DeWalt & DeWalt, 2001).

During the first four weeks, the researcher came to the newsroom at least four days a week, each time spending two to four hours in the newsroom, observing and talking with journalists. In addition, the researcher accompanied some journalists on their reporting assignments to public meetings, crime scenes and other events, including the Spurs’ championship game. During the second four weeks, the researcher conducted semi-structured interviews with 18 Express News reporters, editors and online editors, including six reporters and editors who participated in the game-night coverage. Each interview lasted between 40 to 90 minutes and were audio recorded and later transcribed. Aside from these sit-down, one-on-one interviews, there were also dozens of shorter, less formal interviews with journalists regarding their operations. This study draws upon both the semi-structured and less formal interviews with journalists who covered the game, as well as those who did not. Per IRB requirements, no individual is named in this article, although the newspaper has agreed to be identified.

Documents used in this study are news artifacts related to the coverage under investigation, including digital replica of the newspaper, screenshots of the website and reporters’ Twitter postings. Some of the screenshots were taken on the game night and those webpages are no longer available. Some, such as the Twitter postings, were gathered after the game. The field notes and interviews are examined together with the news artifacts to provide a rather comprehensive assessment.

Results

The first part of this section, “The Operation,” answers the first research question about how the Express News practices omnipresent journalism in its coverage of the Spurs’ championship game. The second part of this section, “Implications for journalism,” answers the second research question about this approach.

The Operation

The San Antonio Spurs advanced to the 2014 NBA finals after defeating the Oklahoma City Thunder on May 31, 2014, in the sixth game of the Western Conference finals. They faced the Miami Heat for the second consecutive year in the finals. The year before, the Spurs lost to the Heat after a gruesome seven-game battle. They were ready to reclaim the trophy in the summer of 2014.

The Spurs won the first game of the series on June 5 but lost the second game three days later. They came back to win the third and fourth games and were only one win away from their fifth NBA title. Game 5, scheduled for Sunday, June 15, was to be held in San Antonio and the enormous excitement that had been building up in the city reached its apex. “Go Spurs Go!” had become the punchline for just about every conversation and everybody in the city had donned a Spurs jersey, it seemed, including several editors and reporters in the Express News newsroom. As the rest of the city was preparing for the ecstasy of welcoming back the NBA trophy in the hands of their beloved Spurs, the newsroom had been preparing for the news coverage of that huge moment.

Planning

On Friday, June 13, the metro editor was going around the newsroom, telling reporters about their assignments for the game night. At 5:30, a meeting was convened. At the meeting were several interns, the metro editor, two other editors, a Web editor, a feature writer, and a couple of reporters.

The metro editor assigned about a dozen reporters to several locations across the city, including a couple of sports bars, a local theater where fans gathered to watch the game, and downtown, where the post-game celebration would take place. (Reporters sent to the AT&T Center, where the game would be played, were from the Sports Desk, which was outside the parameter of this study)

The metro editor told the reporters that each of them was expected to send out three to five tweets of the scene, and post videos and photos of the fans. “We want you to live tweet,” said the metro editor. “As soon as you reach your post, we want you to start tweeting, taking pictures.” The feature writer mentioned to the reporters that if Twitter didn’t go through, use a text message service that would send the text message to Twitter. “Old school always goes through,” the writer commented.

The Web editor asked the reporters to email her their vignettes—quick, short snap shots of interesting moments, mini stories of no more than five paragraphs. Reporters were also urged to make sure their mobile phone was fully charged and bring a charger to the assignment, since they would be mostly using their phone to write and send content.

The metro editor told the reporters to send a minimum of four vignettes to mysa.com, and “you should hold back something for the print story.” The print paper was set to publish a main story summarizing fan reactions from across the city and the feature writer penning that story would select material from the vignettes posted onmysa.com. A limited number of vignettes would also be printed and the deadline for filing these vignettes was 10:30 p.m. The deadline for the main story was 11 p.m. “You got to make your deadline. We have zero wiggle room in this plan,” another editor told the reporters. (field notes, June 13, 2014).

Sunday, June 15, the game was on.

Game Night

The reporter arrived at the sports bar assigned to her at around 5:40 p.m. on Sunday. The bar was already packed with only a couple of empty tables. Right after taking a seat, the reporter took a photo of the scene with her phone and tweeted the photo. Pizza was ordered. Throughout the night, the reporter would sit down and take a few bites, get up to do some reporting—interviewing, taking photos or videos, tweeting, and writing—and then come back to the table when she got a moment to take a few more bites.

She talked with some fans and the waitresses and jotted down some notes, but recorded the conversation on her phone and transcribed from her phone when writing the story. “They talk too fast. They are too excited. I’m not fast enough,” she said. After using her phone for some time, she took out her laptop. She was trying to upload the videos on her phone to Brightcove, an online video hosting platform, and then tweet the link. But her phone wouldn’t upload the video and she had to transport the videos to her laptop and then upload using the laptop.

After the game started, the bar became noisier: about 10 TV sets all around, approximately 100 excited fans shouting, laughing, and talking. The reporter said she needed a quiet place to transcribe interviews from her phone so she went out to the patio. While sitting outside, she spoke to more fans. She sat at the picnic table on the patio and typed on her laptop for more than one hour, as the sky went from the golden twilight to completely darkness (field notes, June 14, 2014). She came back inside when the game was in the last quarter, around 9:30 p.m., sent out a couple of more tweets, including a video of fans chanting “Go Spurs Go” in the final moment of Spurs’ win, before signing off for the long night. The following video shows the actions and atmosphere inside the sports bar.

Based on the tweets and vignettes collected after the game, the reporter sent out 12 tweets (before the game, the tipoff, during the game, fan pictures, fan videos, links to the live coverage on the mysa.com, etc.) and four vignettes during a time period of nearly five hours, from one hour before the tipoff, when she first arrived at the bar, to about one hour after the game was over. Besides that, she wrote a short story for the print paper.

The Outcome: Three Rounds of News Presentation

The outcome of this operation was a coverage of the game night presented in three rounds, on different platforms at different times.

The first round of presentation was the reporters’ tweets. The reporter being shadowed, as well as other reporters in other locations across the city, took photos and videos of the scene upon their arrival and tweeted fan reactions throughout the game (field notes, June 17, 2014). They tweeted big scenes in various venues, close up shots featuring fans waving flags, posing in Spurs jerseys, holding a board cutout of the Coyote, the Spurs’ mascot, among other fan festivities, as well as videos of them chanting, honking, dancing, etc.

The website staged the second round of presentation as it gathered and presented, in real time, vignettes, photos and videos emailed or tweeted by the reporters. By the third quarter of the game, the home page had been updated to feature the story of fan reactions from across the city, titled “Spurs fans watch Game 5 around S.A.,” with a slideshow displaying photos and videos taken by reporters and photographers. Many of the photos were fetched directly from the reporters’ tweets. The story itself is an aggregation of vignettes written by reporters, each about 100 words, with time and location as the heading and the reporter’s name at the end.

The body of the story kept growing as reporters kept sending in vignettes throughout the night. This is very similar to live blogging, where time stamped material is added progressively to the body of the story in a reverse chronological order, with the latest update at the top of the webpage. This format has been used by other news websites, such as The Guardian, to cover major sports games as well as breaking news like the 2005 London subway bombing (Thurman & Walters, 2012). The slideshow kept growing as well. By the morning of June 16, it had more than 300 photos and videos. The story and the slideshow were shareable on Google+, Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest and more. Following are two screenshots of mysa.com from the game night.

The print paper was the last product to be put together that night and formed the third round of presentation. The next morning, people around the city saw the Express News with a giant, full-page photo featuring key players holding the trophy with big grins and a huge headline: Redemption. Cinco! (Spanish for “five”). Inside the A section are three pages of coverage of the win. There is the main story summarizing fan reactions across the city during and after the game, with many segments taken from the vignettes posted on mysa.com the night before. There is another story about fans who attended the game at the arena, and five standalone vignettes by five different reporters, including the one the researcher accompanied.

To answer RQ1, the Express News carried out omnipresent journalism, temporally and spatially, through three rounds of news presentation. In terms of time, the coverage spanned from at least one hour before tipoff until way past the end of the game, and the coverage of the fans’ celebration continued into the next day, as the homepage of the website on Monday morning was all about the post-game celebration. In terms of space, the coverage can be viewed everywhere: on the computer, the phone, the website, Twitter, other social media through sharing, and finally, the print paper.

Meanwhile, the process of such omnipresent journalism was unfolding right before the public eye through the three rounds of presentation, with Twitter being the rather raw reporting, the website aggregating with some curation, and finally the print carrying more refined stories. The process was no longer invisible to the public, but in full display online and on social media. The journalistic product consumed by the audience was no longer just the finished print paper as it was in the old times, but the entire process, from the raw material on Twitter to more polished stories in print. In fact, for the coverage to be omnipresent, to occupy all the time and space, it is almost necessary for the news organization to present the entire process rather than just one finite product. Omnipresent journalism is also journalism of process.

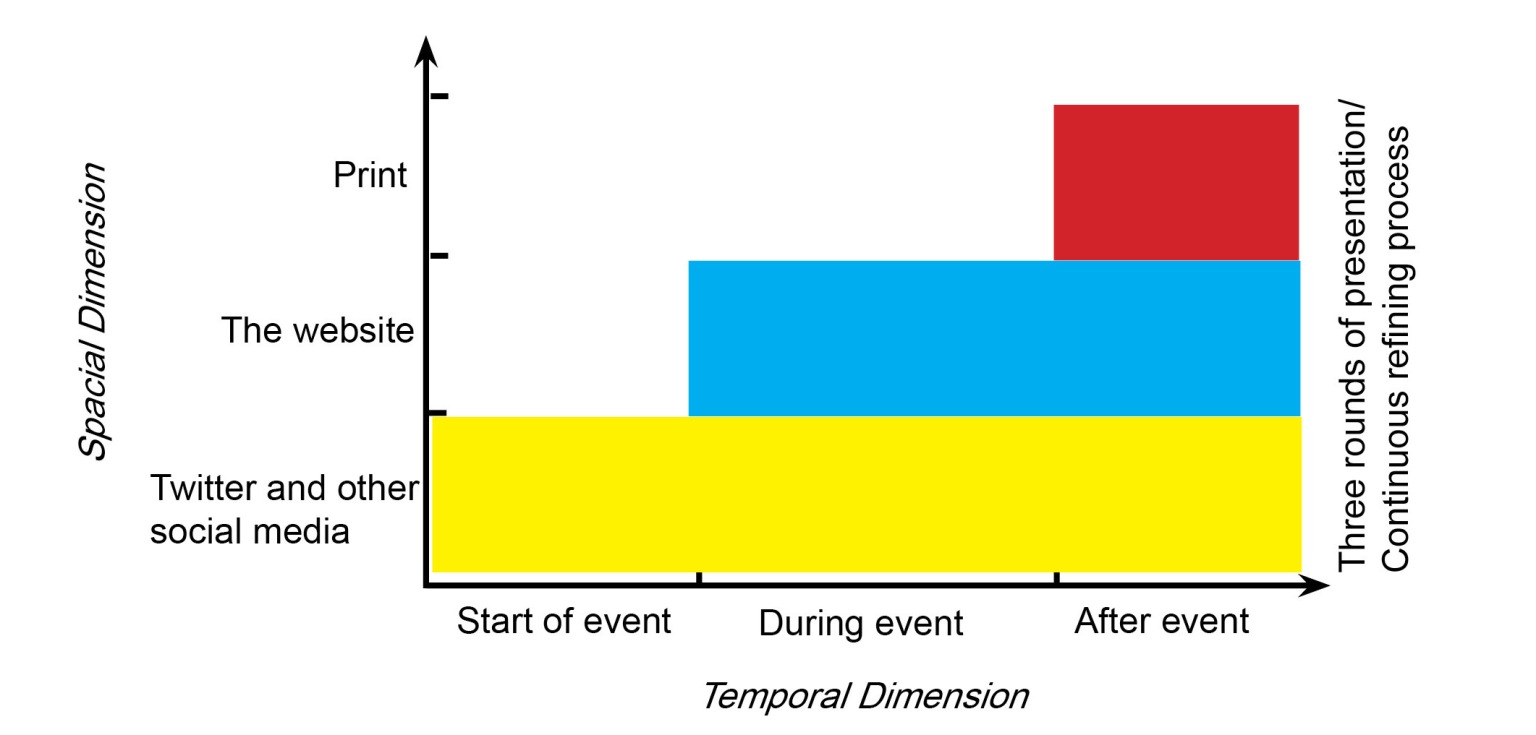

Figure 1 illustrates the key elements of the concept of omnipresent journalism discussed above.

Figure 1: The Concept of Omnipresent Journalism

Implications for Journalism

Having demonstrated the process of the process, this section answers RQ2 regarding the broader implications of omnipresent journalism from four aspects: mobile journalism, multitasking while prioritizing, the print paper as the Holy Grail and glitches.

Based on observations in the newsroom, the three rounds of presentation are routinely employed. Be it community events, school board meetings, or city council meetings, reporters would always take photos of the scene and tweet them right away, usually before the event even started. Several education reporters said they often live tweet the school board meetings (interviews, July 7, 18, 2014). When the news is important enough, reporters would write a short blurb to be posted on mysa.com as soon as possible, and then they would do more interviews throughout the day and develop the story into something more substantial and polished to be printed. The newspaper tries to be omnipresent not just during a major event like the Spurs game, but every single day. And therefore, the following discussion of the implications, even though mostly based on the game coverage, is for journalism in a broader sense.

The Rule of the Day: Mobile Journalism

Observations and conversations with journalists throughout the fieldwork unmistakably point to one major player in today’s news coverage: the mobile phone. The reporter at the bar used her phone to take photos and videos and tweeted them. She also used the phone to record the interviews. As an experienced journalist, she brought her laptop in case her phone wouldn’t work in some scenario, which turned out to be exactly the case.

Other reporters covering the game, who were considerably younger, said they did not bring a laptop and worked entirely from their mobile phone, with some help of the classic notebook and pen. One of them said the phone was much more portable while the laptop was bulky and inconvenient. “When I need to get up, I would have to close the computer and put it away” while a phone can be carried everywhere easily. In other words, the mobile phone is essential, and the laptop is optional. In fact, the Game 5 coverage can be seen as a new kind of news-making practice that would have been impossible without the mobile phone (Westlund, 2013). Mobile journalism, journalism produced and consumed on the mobile phone, has become the rule of the day.

Nor would have the coverage been necessary, perhaps, if not for the mobile phone. The need to produce such omnipresent journalism is mostly driven by the omnipresent mobile phones: they are always on, carried everywhere, and always demanding something to show. People at the Express News are very aware of the power of the mobile phone and what comes with it, such as social media and shareability. “It’s all about getting it out there and engaging the readership,” said a Web editor (interview, July 23, 2014). The importance of the mobile phone has become a widely acknowledged industry trend. “I think we just want to be where people are, and we want to provide them great experiences wherever they are,” says Dan Check, vice-chairman of The Slate Group (Mullin, 2015, para. 8).

In short, the omnipresent mobile phone has made it necessary for news coverage to be there all the time and on multiple platforms. Omnipresent journalism is made possible largely by mobile journalism.

The Multitasking, and Prioritizing, Journalists

To accomplish such omnipresent journalism—during the big event as well as daily reporting—journalists are destined to multitask, which puts more demand on the journalists.

Throughout the coverage of the Spurs’ game, the reporter being observed was multitasking the entire time. Working with two screens simultaneously, she took photos and videos on the phone and then uploaded the material to the laptop, recorded the interviews on the phone and listened to the recording and wrote the story on the laptop. During that night, she was juggling interviewing, photo shooting, tweeting, writing stories, texting and filing stories, and keeping herself from starving. Her job was not just to report and write, but also to take visual materials and tweet live. She was performing multiple tasks simultaneously, as a reporter, photographer and social media contributor. She was not alone. Another reporter said he had his phone in his hand, pen in his mouth, notebook tucked between his chin and neck, when he needed to type something on the phone while still doing interviews.

To handle such demanding tasks successfully, reporters not only need to train themselves into proficient multitaskers, but also learn another necessary skill: prioritization.

Multitasking without prioritization is only going to lead to more stress and possible failure. In today’s newsroom, reporters face multiple deadlines. On the game night, for example, the deadline for live tweeting was, of course, immediate. The deadline for the vignettes to be posted on the website was ongoing but imminent. The website wanted to post fresh material as soon as possible and update frequently. In addition, the reporters were supposed to write vignettes for the next day’s paper, and those vignettes should be different from what was already posted on the website. The deadline for the print piece was 10:30 p.m.

Given the rolling deadline, reporters needed to learn to prioritize the tasks. The reporter being observed on the game night sent out tweets as soon as she arrived at her assigned location, just to get something out first. She then spent time doing interviews for the vignettes. She got a text message from an editor asking for the vignettes and she sat down to write them on the patio. While she was writing, she ran into another group of fans and spoke with them, and took some photos and video. Then she decided she needed to prioritize the writing because the website needed something to post as soon as possible and the 10:30 deadline for the print piece was approaching. That was when she told the fans, who were still talking with her about their love for the Spurs, “Okay, I got to file this. I have half an hour to write this.” The fans left and the reporter sat alone in the dark on the patio to finish the writing (field notes, June 15, 2014; interview, July 7, 2014). After she filed her story, she tweeted the photo and video she took of another fan, indicated by the time stamp on her tweets. Apparently, she prioritized writing over live tweeting at that point of time, when facing imminent deadlines of filing vignettes. She mentioned using similar strategies for other assignments as well, all because she needed to live tweet, break the news onmysa.com, and still write a full story for the print paper.

Prioritization thus becomes a new, important skill to learn. Said this reporter: “It takes some level to understand what’s expected of you and what you can produce. To understand, okay, well, if I need to produce this, it’s gonna require this much time, so I better start addressing that now” (interview, July 7, 2014). According to another reporter, the key here is finding the balance. “How much should I be tweeting, how much should I be interviewing people, how much should I be writing or taking photos right now?” (interview, July 14, 2014). These are indeed the questions that the multitasking journalists need to figure out in order to meet the demands of omnipresent journalism.

The Holy Grail: The Print Paper

The three rounds of presentation: live tweets, website, and print, constitute a continuous refining process. In this process, for better or for worse, the print product has become something like the Holy Grail of journalism, highly valued and sought after by journalists. This phenomenon will be explained through tracking one particular episode reported by the reporter being observed, as it went through the refining process.

Soon after the game’s tipoff at 7 p.m., the reporter met in the bar a father with a daughter, both wearing sparkling golden fedoras to express their anticipation of winning the trophy. The reporter took a photo of them and tweeted it right away: “The Balakit family is all blinged-out in honor of the @spurs #GoSpursGo.” This tweet is pretty much raw material, as the reporter simply took a photo and tweeted it instantly, without much modification.

By 9 p.m., this same photo was included in a slideshow put together by mysa.com to accompany the collection of vignettes titled: “Spurs fans watch Game 5 around S.A.” In the slideshow, the cutline of this photo is slightly different from the tweet: “The Balakit family is all blinged-out in honor of the Spurs as they watch Game 5 at Freetail Brewing Co. on Sunday, June 15, 2014.” The Web editor had been monitoring reporters’ Twitter accounts and getting photos from the tweets. When the photo showed up on the website, it was already a piece of raw material repurposed. It was no longer a standalone tweet but part of a slideshow of hundreds of photos and videos taken by various reporters and photographers. The photo was now curated and reorganized as part of a different product, although the photo itself has not been modified. The cutline of the photo was mostly copied and pasted from the tweet, less the @ and # but adding time and location to fit the format of the slideshow. The spontaneous tweet was now slightly refined.

But it was not until the reporter wrote the story for the print paper that background of the photo was really fleshed out. She featured this father and daughter in a short story about how the game made the Father’s Day special for some fans. Another family of fans was also mentioned in the story. It had vivid details and quotes that could not have been presented with 140 characters.

At the planning meeting two days earlier, editors had instructed the reporters to save the best material for the print (field notes, June 13, 2014). The reporter observed by the researcher followed that instruction. Among all the tweets and vignettes she produced that night, the print story took the most time to write and was the most thoughtful piece. By the time it appeared in the paper, it had gone through a couple of editors and designers, becoming a rather refined product. The story was nicely laid out with the other four vignettes, side-by-side in single columns, with a big, cross-page photo on top and a banner headline: “S.A. celebrates its team.” The paper was sold out.

Among a dozen of reporters dispatched to cover fan reactions that night, only five of them had a bylined, standalone vignette printed in the next day’s paper.

During the eight-week field research, various reporters and editors expressed their high esteem for the print product. “I kind of see the printed word as the most valued. It costs more. It’s more work to produce. There is more thought put into it,” said a 58-year-old editor. “Deep down inside, that is what journalists today still want” (interview, July 2, 2014). The editor was largely right. The reporter being observed, who is in her early 30s, said she felt the real marker for quality journalism is still the stories that are “good enough to get in the paper. For me, it means more to have a story on the front page than just posted online” (interview, July 7, 2014).

Even interns in their early 20s agree. “I’m more excited opening up the paper and seeing my story than just being able to look at it and send people a link,” said one intern. “Anybody can post something online, on the blog; but not everybody gets the stuff actually printed. So yeah, I like seeing my stories in print better.” Indeed, a byline in print symbolizes authority and carries a sense of validation (Robinson, 2011).

When it is so easy to tweet and post articles online with virtually no space limit, the print product becomes a scarce resource that presents only the best of the best, hence marking the quality of journalism. The question is, if one day all newspapers cease to be printed, what would journalists hold as the marker of quality journalism? For now, the Express News, as many newspapers around the country, is a hybrid of print and online journalism. Having both fits the omnipresence strategy, in time and places, and creates some sort of synergy (Westlund, 2012; Westlund & Fardigh, 2011).

The Glitches

Omnipresent journalism, meanwhile, encounters inevitable glitches. Technological glitches are commonplace. The reporter at the bar could not upload videos from her phone to a website and had to transfer the videos to her laptop, spending more time and effort. A couple of other reporters had trouble posting tweets due to poor Internet connections, and one of them resorted to the texting service that sent text messages to Twitter (field notes, June 15, 17, 2014; interviews, July 7, 14, 2014). As an editor said, in a world that is filled with devices, journalists sometimes are at the mercy of technology (interview, July 2, 2014). They often find themselves having to do more digital troubleshooting than content editing (Robinson, 2007).

There are also human errors. Having to juggle between the website and the print posed some challenges in a major coverage like the Spurs game. The reporters were supposed to send vignettes to be posted on mysa.com throughout the night and the main story in the print paper would draw on these vignettes. The reporters were also instructed to set some material aside, supposedly the best material, for the next day’s print paper only. One reporter, however, confused these different type of stories and filed the same story to both the website and the city desk, resulting in the same episode appearing on mysa.com during the game, and in both the main story and the standalone vignette in the print paper the next day, an editor said (field notes, June 17, 2014).

Discussion and Conclusion

This case study explored how the San Antonio Express News practiced omnipresent journalism in its coverage of the Spurs’ NBA 2014 championship game. Such omnipresent journalism is accomplished in two dimensions—temporal and spatial—and through three rounds of news presentation—live tweets, real-time website updates and the newspaper. As such, the coverage was done in real time of the game and appeared on multiple platforms: Twitter, website, print, and other social media through sharing, to be viewed on the phone, other mobile devices, computer, and in print. The three rounds of presentation allowed the audience to consume not just a slideshow or article, but the entire process of news production. Omnipresent journalism, therefore, is journalism of process, in that the process has become an integral part of the product.

Such omnipresent journalism has broader implications for journalism in general. In the journalistic practice that strives to be omnipresent, the mobile phone plays the vital role, both in terms of the need to cater to people’s news consumption habits and being the essential tool for journalists. The demand of omnipresence puts a rather high demand on journalists, who have to be proficient in multitasking while still knowing how to prioritize their tasks as they face several different deadlines for different type of content they are tasked to produce. A lot of the content they produce on a daily basis, including the game night, is for online platforms, be it live tweets (text, photo, video, etc.) or website updates. But they save the best for the print, as the print is the last and most refined product of the day, and journalists have a very high esteem for the print product. Needless to say, from the first tweet of the scene to the newspaper being put together, it is often a long day for the reporters and editors and they have to brace themselves for possible glitches.

With analysis of both the temporal and spatial aspects, this study advances the concept of omnipresent journalism to be more comprehensive and have more interpretive power. The concept can be used to theorize an emerging mode of news production at newspapers; a mode that integrates the traditional/print and the emerging/online journalistic practice. The concept as presented in this paper also bridges the old and new theories of journalism studies. On the one hand, it resonates with the well-established concept of journalistic routines (Reese, 2001; Tuchman, 1978), which has played a significant role in the study of legacy media. On the other hand, it touches upon emerging concepts, such as distributed content, associated with the newly developed digital media.

However, the researcher would caution against deeming the omnipresent journalism as discussed in this paper as the ultimate solution to all the challenges facing the newspaper industry. There is a possibility that after a while, newspapers will find yet another way of producing and distributing news, because the challenge remains for newspapers to hold onto an audience big and stable enough to sustain the business of newspaper publishing, if it is sustainable at all. The newspaper industry is now facing strong competition from the digital native news outlets, such as ProPublica, BuzzFeedand Vox. These outlets are keen to innovate journalistic storytelling and are good at it, which gives them an edge in competing for the millennials (Jurkwitz, 2014).

For now, it suffices to say that such omnipresent journalism is necessary for the newspaper industry to stick around. Or, the industry simply cannot afford not being omnipresent. “The more pressing concern for the industry is making sure people are continuing to read our work,” said one reporter (interview, July 7, 2014), and newspapers have to go after the readers wherever they are, which means to present news anytime, anywhere: in real time, online, in print, distributed across social media, through websites as well as phone apps. A more distributed media ecosystem, as what is happening now, is where the content will go to the people more than the people will go to the content, according to Jeff Jarvis, director of the Tow-Knight Center for Entrepreneurial Journalism (Mullin, 2015). Being omnipresent, it seems for the time being, increases the chance of being noticed. The page views of the mysa.com on the night of the Spurs triumph spiked during the hours between 9 p.m. and 11 p.m., totaling more than 260,000 page views in those three hours, more than doubling the page views at the same hours a week earlier and a year before that.

Future studies could perhaps explore a bigger question: how much journalistic value is there in such omnipresent journalism? Does the concept of live tweeting enhance the calling of the profession (Robinson, 2011)? Or, in other words, does omnipresence make better journalism? Future studies could also conduct similar research in other newsrooms and examine to what extend such three-round news presentation is a pattern across the newspaper industry, or other legacy news organizations.

References

Atkinson, P. & Coffey, A. (2003). Revisiting the relationship between participant observation and interviewing. In J. A. Holstein, & J. F. Gubrium (Eds.), Inside interviewing: New lenses, new concerns (pp. 415-428). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Barthel, M. (2015). Newspaper: Fact sheet. Retrieved December 19, 2015, fromhttp://www.journalism.org/2015/04/29/newspapers-fact-sheet/

Berkowitz, D. (1989, August). Notes from the newsroom: Reflecting on a naturalistic case study. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication, Washington, D.C.

Brock, G. (2013). Out of print: Newspapers, journalism and the business of news in the digital age. London, UK: Kogan Page.

Cottle, S. (2007). Ethnography and news production: News developments in the field. Sociology Compass, 1(1), 1-16.

DeWalt, K. M. & DeWalt, B. R. (2001). Participant observation: A guide for fieldworkers.Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

Heckman, M. (2013). Chronicle’s new pay site spurs competitors. Retrieved December 21, 2015, from http://www.netnewscheck.com/article/23945/chronicles-new-pay-site-spurs-competitors

Fishman, M. (1980). Manufacturing the news. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Gans, H. J. (1979). Deciding what’s news: A study of CBS Evening News, NBC Nightly News, Newsweek, and Time. New York, NY: Pantheon Books.

Gitlin, T. (2003). The whole world is watching. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Heim, K. (2015). Live tweeting a presidential primary debate: Comparing the content of Twitter posts and news coverage, #ISOJ 5(1), 208-228.

Jenner, M. (2012, April). Diving into mobile: The mobile phone and tablet products of dailies and weeklies. Paper presented at the American Society of News Editors Convention, Washington, D.C.

Jurkowitz, M. (2014, March 26). The growth in digital reporting: What it means for journalism and news consumers. Pew Research Center. Retrieved December 19, 2015, from http://www.journalism.org/2014/03/26/the-growth-in-digital-reporting/

Jurkowitz, M. (2014, March 26). The losses in legacy. Pew Research Center. Retrieved December 19, 2015, from http://www.journalism.org/2014/03/26/the-losses-in-legacy/

Kamarck, E., & Gabriele, A. (2015). The news today: 7 trends in old and new media.Retrieved December 19, 2015, fromhttp://www.brookings.edu/research/papers/2015/11/10-news-today-7-trends-old-new-media-kamarck-gabriele

Mabweazara, H. M. (2013). Ethnography as negotiated lived experience: Researching the fluid and multi-sited uses of digital technologies in journalism practice. Westminster Papers 9(3), 99-120.

Marchionnia, D. (2013). Conversational journalism in practice. Digital Journalism, 1(2), 252-269.

Mitchell, A. (2015). State of the news media 2015. Retrieved December 31, 2015, fromhttp://www.journalism.org/2015/04/29/state-of-the-news-media-2015/

Mullin, B. (2015). Apple’s news, which launches today, is the latest in a trend toward distributed content. Poynter. Retrieved December 18, 2015, fromhttp://www.poynter.org/2015/apples-news-which-launches-today-is-the-latest-in-a-trend-toward-distributed-content/373305/

National Newspaper Association. (2015). Newspaper circulation volume. Retrieved December 19, 2015, from http://www.naa.org/Trends-and-Numbers/Circulation-Volume/Newspaper-Circulation-Volume.aspx

Paterson, C. (2008). Why ethnography. In C. Paterson, & D. Domingo (Eds.), Making online news: The ethnography of new media production (pp. 1-11). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Purcell, K., Rainie, L., Mitchell, A., Rosenstiel, T., & Olmstead, K. (2010). Understanding the participatory news consumer. Pew Research Center. Retrieved fromhttp://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2010/Online-News.aspx?r=1

Reese, S. D. (2001). Understanding the global journalist: A hierarchy-of-influences approach. Journalism Studies, 2(2), 173-187.

Robinson, S. (2007). Someone’s gotta be in control here. Journalism Practice, 1(3), 305-321.

Robinson, S. (2009a). A chronicle of chaos: Tracking the news story of Hurricane Katrina from the Times-Picayune to its website. Journalism: Theory, Practice and Criticism, 10(4), 431-450.

Robinson, S. (2009b). The cyber-newsroom: A case study the journalistic paradigm in a news journey from a newspaper to cyberspace. Mass Communication and Society, 12, 403-422.

Robinson, S. (2011). “Journalism as process”: The organizational implications of participatory online news. Journalism & Communication Monographs, 13(3), 137-210.

Thurman, N., & Walters, A. (2013). Live blogging: Digital journalism’s pivotal platform?Digital Journalism, 1(1), 82-101.

Tuchman, G. (1978). Making news. New York, NY: Free Press.

Westlund, O. (2012). Producer-centric versus participation-centric: On the shaping of mobile media. Northern Lights, 10, 107-121.

Westlund, O. (2013). Mobile news. Digital Journalism, 1(1), 6-26.

Westlund, O., & FÄRDIGH, M. A. (2011). Displacing and complementing effects of news sites on newspapers 1998-2009. The International Journal on Media Management, 13, 177-191.

Zhaoxi (Josie) Liu is an assistant professor at Trinity University in San Antonio. She used to be a journalist and focuses her research on cultural inquiries of journalism practice and inter-cultural communication.