“We are the 200%”: How Mitú constructs Latino American identity through discourse

By Ryan Wallace

[Citation: Wallace, R. (2020). “We are the 200%”: How Mitú constructs Latino American identity through discourse. #ISOJ Journal, 10(1), 13-33.]

Focusing on a digital native publication, this study uses the example of mitú to understand how culturally-specific content may be transforming the ways in which news and culture are articulated to online news audiences. In order to analyze the diverse messages constructed by mitú and their intended purposes, this study used a critical discourse approach to deconstruct mitú’s content across multiple platforms and symbol systems. Aside from directly confronting notions of patriarchy, machismo, and other hegemonic ideologies within Latino American culture, mitú’s discourse illustrates the formation of a broader Latino American identity—acknowledging the diverse intersectional characteristics of this group.

While contemporary journalism has had a long tradition of empowering democratic societies and informing mass audiences, critiques of the industry’s maleness and whiteness have raised significant questions about who it is that journalists envision their audiences to be. News has been described as an elite form of discourse, created and reproduced to reinforce existing socioeconomic hierarchies (Van Dijk, 2013). But as new generations of Americans are becoming increasingly engaged with news media, some publications are beginning to think outside of the box, to not only engage diverse audiences but produce content tailored to the experiences and cultures of what were once considered to be minority groups in the United States. One such media company, mitú, not only challenges traditions held by journalists in the United States, but also those throughout Latin America. As a digital native, the company has created a vast network of audiences with a global reach—averaging more than two billion monthly views for its creative content (Graham, 2016). And as a form of Latino journalism, mitú is creating culturally-relevant content for Latino American audiences and directly challenges the ways in which this multicultural group has been represented in the news and other forms of media (Acevedo & Beniflah, 2018). It also tackles ideological values deeply ingrained in Latino culture that serve as biases against gender, race, sexuality and color. Through both its discourse and organizational structure, being co-founded by Latina Beatriz Acevedo and having elevated other Latinas to executive roles in senior leadership, mitú proves to be an interesting case study for investigating how contemporary journalism is being reimagined in the United States—challenging sociocultural power structures, privilege across cultural contexts, and patriarchy.

Connecting with more than 90 million readers each month, mitú is a brand that acknowledges the increasing multiculturality of the United States and is developing multidimensional content that appeals to Latinos born in the United States (Acevedo & Beniflah, 2018). Their inspiration and their audience is what they refer to as “the 200%—youth who are 100% American and 100% Latino” (We Are Mitu, 2019). And while still technically considered a minority group in the United States, this audience represents a growing force in the American population. According to recent census data, over the past decade Latinos have accounted for more than half of the nation’s population growth, while Millennials are projected to soon become the largest living adult generation in the United States (Pew, 2014, 2018a). At the intersection of these two groups is a diverse population of individuals, with mixed ethnic and cultural backgrounds. And though their numbers are growing, recent data suggests that Latino Americans have serious concerns over their position in the United States—as recent policies and racism have specifically targeted Latinos during the Trump presidency (Pew, 2018b). By using social media and journalism to represent these realities, mitú is engaging audiences with “Things That Matter” through the lens of what makes them connected, rather than different (We Are Mitu, 2019).

This study takes the example of mitú to better understand how digital native publications are now creating opportunities for moving beyond traditional journalistic roles. By analyzing mitú’s discourse, it looks at how culturally specific news and other media content can be used by news media in order to challenge ideological hegemonies like notions of patriarchy. It also brings to light ways in which journalism may be working beyond traditional roles to help construct new identities for its audiences—by articulating the complexity of Latino American racial, gendered, and sociocultural diversity. This study analyzes mitú’s discourse to better understand how Latino American identity is constructed through confrontation with traditional ideological hegemonies. The research questions it seeks to answer are significant, as they bring together two theoretical strands of Latino journalism and hegemony, particularly during an era when both journalism and Latino American identity are being openly challenged in the United States. Just as mitú seeks to reach underrepresented audiences and address the multiculturality of the United States, this study brings attention to how particular ethnic and cultural groups are challenging hegemonies and using different media to reconceptualize what is journalism in a contemporary context.

Literature Review

Legacy News Media

Emerging at the turn of the seventeenth century in western Europe, contemporary journalism began as a feature of the printing revolution (Wahl-Jorgensen & Hanitzsch, 2009). From the beginning, early newspapers targeted a particular audience of social elites and spoke to positions of power (Wahl-Jorgensen & Hanitzsch, 2009). News as a form of mass communication did not take shape until the eighteenth century, when it emerged as a form of discourse for representing and informing public opinion (Wahl-Jorgensen & Hanitzsch, 2009). While journalism spread across western Europe, the modern conception of journalism and its news values are believed to be a product of Anglo-American invention (Chalaby, 1996). This historical context of contemporary journalism is important to understand because of the central role that Anglo-American ideological values played in the creation of the modern press (Chalaby, 1996).

Journalism co-evolved with the American nation itself, so much so that the two became inextricably interrelated (Chalaby, 1996). While this can be seen in the conception of a “free press” in the United States, it can also be seen by the role that the English language and Anglo-Saxon identity play in the production and representations of news media—not only are they central, but they also contribute to the dominant hegemony (Chalaby, 1996). Because news is a social construction that is not discursively neutral, these foundational values are important factors for analysis of how journalism contributes to the formation of a social reality (Broersma, 2010). In particular, as this study focuses on the growing importance of media that speaks to specific racial/ethnic audiences, it is vital to recognize journalism’s role as a symbolic process that creates, recreates and maintains social reality (Broersma, 2010). And, in particular cases, can also largely contribute to the social construction of racial/ethnic identity.

Latino Journalism

As a form of journalism that is created with a particular audience in mind, both in the modes of production of media and in the central focus of their narratives, mitú is a contemporary illustration of Latino journalism. Latino journalism is strategically and purposefully created for the 200%—those that are at once American and Latino. This form of discourse is unique in that through it the Latino identity is denationalized, recognizing similarities amongst the collective diaspora, and a new national identity of Latino Americans is created (Rodriguez, 1999). Shared experiences in cultural and social knowledge serve as touchstones for this new national identity, as well as shared struggles with power (Rodriguez, 1999). Through a unique and detailed symbol system, Latino journalism constructs the social reality of Latinos living in the United States by relating their identity to other Latinos—creating a narrative that shows Latinos around every corner of American life (Rodriguez, 1999). Although two of the key motives of Latino journalism (as a form of cultural preservation or recreation, and as a way to situate Latinos into the dominant society) have been written about, few studies have investigated how Latino journalism serves as a form of cultural resistance to hegemony (Rodriguez, 1999). Using mitú as a contemporary case of Latino journalism, this study brings to light concrete examples of these motives in practice and introduces new lines of inquiry into theories of identity and the effects that journalism can have on society.

In order to understand the discourse of Latino journalism, it is important to consider the central motives of these practices and how they relate to broader sociocultural hegemonies (Lazarte-Morales, 2008). This form of journalism is articulated around the interplay between power and differences, conveying complex dimensions that not only serve as critical lenses through which the news can be viewed, but also contribute to the construction of a new group identity (Lazarte-Morales, 2008). Resulting as a consequence of contemporary American xenophobia, representations of Latinos in the United States and for Hispanic audiences are inherently tied to political and cultural power (Rodriguez, 1999). In fact, by analyzing the construction of a Latino American audience, researchers must consider the political, economic and social dimensions of various communities (Rodriguez, 1999). In the United States, Latinos are often treated as a homogeneous group (Cauce & Domenech-Rodriguez, 2002). However, multiple waves of immigration have brought groups of individuals from various regional, economic, and racial groups into the United States (Cauce & Domenech-Rodriguez, 2002). For these reasons, Latino journalism must report differences in a nuanced way that acknowledges the complexity of many factors, but also coalesce similarities in order to construct a new Latino American identity.

In recent decades, journalism as a broader industry has become transformed by the introduction of new technology (Fenton, 2010). The rise of the Internet and digital media have not only changed the modes of production for journalists, but have also changed the dynamics of what information could be relayed to news audiences (Fenton, 2009). With the introduction of hyperlinks and ease of sharing multimedia content like video and audio, online news publications are able to supply their audiences with greater context than ever before (Fenton, 2009). And now, as the Internet has become as ubiquitous as journalism, the industry is beginning to see the emergence of “digital native media”—news publications that were born and grown only online (Wu, 2016). Digital native media differ from traditional news publications in many ways, but perhaps most importantly in their ability to benefit from digital networks and use of the affordances of different social platforms to create multimedia content that directly speaks to an online news audience (Wu, 2016). As a digital native publication, mitú represents an interesting case study for looking at how Latino journalism is articulated in an online environment.

Race and Ethnicity in the United States

Race and ethnicity are complex social constructions based on a myriad of traits ranging from ancestry and nationality to physical appearance and culture (Renn, 2012). In the United States, these social categories have been significant not only as they are used for identification of social groups, but also for the creation of individual and group identities (Renn, 2012). Individual experiences in the United States are seen through the lenses of race, culture and nationality, so much so that they are significant factors at the foreground of conceptions of identity (Renn, 2012). As a widely diverse ethnic group, it is important to acknowledge the mixed-races of Latino people–coming from European, African and Indigenous heritage (Cauce & Domenech-Rodriguez, 2002). Thus, the racial identities of Latinos is vast, with most individuals being bi- or multiracial (Cauce & Domenech-Rodriguez, 2002). How this racial mixture is articulated into contemporary racial identities is complex and often has to do with sociocultural contexts.

Theories of Identity—Intersectionality and Simultaneity

As theories of identity have developed throughout the latter part of the 20th century, scholars began to acknowledge that one aspect of an individual’s identity cannot simply be extracted from their identity as a whole (Renn, 2012). Differences amongst race and ethnicity, therefore, do not illustrate the true complexity of social dynamics. Taking an intersectionality approach, looking at the integrative ways in which social identities are created, it can be seen that race and ethnicity cannot be understood alone without the contexts of gender, sexuality, social class, ability, and other social characteristics (Renn, 2012). Together, the experience of individuals and groups of individuals must consider the multiple, intersecting facets of their identities, as well as how these identities differ from the prevailing hegemony. Intersectionality allows scholars to not only interrogate the dimensions of social categories of differences, but also their similarities and the ever-present role that inequalities play in social context (Azmitia & Thomas, 2015).

To understand how identity contributes to and is altered by broader discourses of power, hegemony and patriarchy in the United States, it is important to turn to another feminist concept—simultaneity (Holvino, 2010, 2012). Transnational feminists developed the notion of simultaneity out of an understanding that identities signify relations of power in social contexts and that other social processes like class contribute to the construction and constant re-articulation of identities (Holvino, 2012). Simultaneity can be defined as “the simultaneous processes of identity, institutional and social practice, which operate concurrently and together to construct people’s identities and shape their experiences, opportunities, and constraints” (Holvino, 2012, p. 172). And this concept not only helps explain existing power structures based on dimensions of identity that may vary from the prevailing hegemony of power, but also how inequality is reproduced through other characteristics (Holvino, 2010, 2012). This understanding of identity allows for a more complex, multi-dimensional view of what it means to be Latino.

In a contemporary digital landscape, the transition from traditional legacy media to those of “social media” have had significant implications for the process of creating, representing and recreating identities in a social context (Manago, 2015). As young audiences transition into adulthood, the Internet and its various platforms provide them with the opportunity to not only construct their identity in the public sphere, but in the digital sphere as well (Manago, 2015). The affordances for self-expression and the ability to actively contribute to the formation of one’s own identity are powerful consequences of social media (Manago, 2015). They not only allow young audiences to consume messages, but also create them on the same screen, and to very strategically craft public personas (Manago, 2015). Digital media, therefore, are important for understanding new networks that are emerging, how people are coming together on social media, and how new publications may help articulate these online identities in meaningful ways.

Patriarchy and Hegemonic Ideologies

Empirical evidence increasingly suggests that an American national identity is pervasive throughout the United States in spite of its members increasingly becoming more ethnically diverse (Citrin et al., 2001). However, the conception of the American identity is far more complex when diversity is addressed (Citrin et al., 2001). Although White members conflate their national and ethnic identities by creating a sense of solely being American, minority groups have begun to describe themselves in plural terms—being at once American and members of distinct ethnic/racial groups (Citrin et al., 2001). This plurality not only results in the simultaneity of multiple identities, but also various ways of encountering similar notions of patriarchy and hegemonic ideologies. In particular, this study looks at news discourse as both a way of promulgating and of confronting ideological hegemonies (Van Dijk, 2009). Questioning how culturally specific news discourse deals with these ideological views, it is important to identify the ideological hegemonies in American culture, but also their analogues in Latino culture.

Similar to the White patriarchal hegemony of the United States, the role of the family has been a significant cornerstone for social education and identity construction for Latinos (Cauce & Domenech-Rodriguez, 2002). In some ways, although it has been posited that the goals of American families of color may be different than those of White families in the process of social education, certain hegemonic ideologies manifest across these groups (Cauce & Domenech-Rodriguez, 2002). However, because they are rooted in distinct cultural norms, particular values are articulated in unique ways for minority groups (Cauce & Domenech-Rodriguez, 2002). For Latinos, values that have been described include: familismo (importance of family closeness), personalismo (importance of personal goodness), marianismo (emphasis on a woman’s role as a mother, who sacrifices and suffers for her children), and machismo (emphasis on a man’s role as head of household) (Cauce & Domenech-Rodriguez, 2002). These values collectively contribute to a larger goal of maintaining stability and tradition in Latino families, however, in the context of the United States they reify hegemonic notions of masculinity, patriarchy and distinct cultural roles (Cauce & Domenech-Rodriguez, 2002).

Other ideological values that are common in Latino culture also contribute to the hegemony of what it means to be American, particularly as it is seen through the lens of race. Pigmentocracy, a stratification system based on the color of one’s skin, is a common practice in Latin American societies and continues into the American context (Bonilla-Silva, 2002). Power dynamics in the United States reflect a similar and often unstated Black-White binary paradigm, where power relations are constructed based on skin color (Delgado & Stefancic, 2017; Rockquemore & Arend, 2002). Historically, race relations have played a significant role in public discourse and in the United States have contributed to structural inequalities in many aspects of everyday life (Rockquemore & Arend, 2002). Although Americans are increasingly acknowledging a transformation of race relations, as racial categories are blurred, inequalities persist (Rockquemore & Arend, 2002).

Expanding the idea that Latino journalism not only can construct social reality but may also construct a new Latino American identity for its audiences, this study uses mitú as a case for understanding how Latino journalism confronts hegemony and patriarchy in the United States. Together, these theoretical strands allow for the following central research questions to be investigated:

RQ1: To what extent does mitú’s discourse construct a Latino American identity?

RQ2: How does mitú’s discourse challenge patriarchy and other ideological notions of hegemony?

In a contemporary context, this study not only seeks to fill an important theoretical gap in the literature, but also seeks to discuss the complexity of Latino identity and how this group is situated within broader ideological hegemonies.

Method

To address these questions, this study relied on qualitative methods to gather a thick description and analysis of mitú’s content across multiple social networking platforms and its digital publication—with particular attention to how processes of race, gender and culture are actively discussed. Through a critical discourse analysis, this study sought to understand how a Latino American identity is articulated by mitú and how its discourse contends with ideological hegemonies that are pervasive in both American and Latino cultures. This method is particularly important for this study because it views language and discourse as social practices, which allows analyses to understand the linguistic and semiotic elements of discourse in addition to the specific context in which this discourse takes place (Fairclough, 2013; Lazar, 2014; Wodak & Fairclough, 2013). As Latino American identity is articulated across multiple symbol systems, this qualitative approach allows for a better understanding of how this complex discourse is articulated. As a method that treats power and ideologies as being intrinsically connected to discourse, as they are reproduced through language and symbol systems, a critical discourse analysis allows for critiques of structural relationships to be made with a particular emphasis on how they are manifested in media content (Fairclough, 2013; Lazar, 2014; Wodak & Fairclough, 2013).

In order to obtain a comprehensive view of mitú’s discourse, this analysis developed a comprehensive, cross-platform corpus. The corpus for this study was gathered in October 2019 by manually scraping all of mitú’s social media content and articles from the publication’s website, including: 15,603 posts from Instagram, 956 YouTube videos, 8,072 original articles from mitú’s website, and a Facebook page with more than five years of content. As the multimedia content throughout this corpus relied on multimodal forms of discourse, borrowing from various symbol systems, this study’s analysis considered not only textual, but visual and aural discourse as well. The following results of this analysis consider both platform specificity, as well as how discourse across these platforms contribute to mitú’s broader discourse about Latino American issues.

Findings

Social Media, Simultaneity, and the Construction of Latino American Identity

While social media content is not entirely a part of mitú’s journalistic discourse, as a digital native publication, cross-platform use of social media is a significant part of the company’s overall messaging. In support of the publication’s mission to “engage [their] audience through a Latino POV across multiple platforms,” social media facilitate the dissemination of news and entertainment content, as well as provide a space for Latino Americans to identify cultural commonalities regardless of their national or racial ties. For these reasons, analyses of mitú’s social media content was at the core of answering RQ1 (To what extent does mitú’s discourse construct a Latino American identity?). As a part of the company’s strategy to engage audiences, on social media they are able to create news, comedy, animations and even nostalgia with multimedia content through a Latino point-of-view. Intertextual cues from popular American and Latin American cultural references, as well as an emphasis on the diversity of Latinos, contributes to the notions of intersectionality and simultaneity—that multiple characteristics can define identity, and that these characteristics can work at the same time to create plurality in how identities are articulated.

Guacardo—“El Aguacate Travieso”

As an anthropomorphic representation of one of the United States’ most notable imports from Latin America, mitú’s clever mascot Guacardo is far more than a naughty avocado. Videos of the cartoon character emerged through the publication’s social media accounts in early 2017, and since then he has become a symbol not only for the publication, but also for its audience. Created by Danna Galeano, a Colombian Latina and one of mitú’s animators, Guacardo is an awkward and comedic character who can often be found dancing or fumbling his way through situations. And although this animation is not directly a part of mitú’s journalistic discourse, his character contributes largely to the publication’s construction of a Latino American identity.

Placed in the context of parodies of music videos and classic films, Guacardo’s content relies heavily on intertextual cues from popular American culture. Borrowing from American entertainment, Guacardo’s character can be viewed as an extended metaphor for Latino Americans’ significant participation in the production and consumption of popular American culture. As seen in Figure 1 Guacardo is often interpolated into scenes lacking Latino or cartoon characters, and in many cases takes on the roles of famous characters in music, television or film. Interestingly, although Guacardo’s character occasionally borrows from Mexican culture (e.g.: wearing mariachi clothing), his identity as articulated through his content remains amorphous. His character does not have a voice or accent, although the written text that accompanies his content is almost entirely in English. And unlike mitú’s other content which is bilingual or refers to intertextual cues from other Latin American nations, Guacardo’s character is deeply embedded in the United States context. These unknown origins of the character and missing cultural cues contribute to the idea of constructing a Latino American identity, without racial or national ties outside of the United States.

This construction of identity is most easily seen through one of Guacardo’s most famous characters, as he embodies the late Selena Quintanilla-Pérez. The famous Latina American singer-songwriter was known as the “Queen of Tejano music,” and since her death has become iconic not only for her music but also for the cultural legacy that she left behind (Paredez, 2009). Her life story served as an illustration of racial and socioeconomic inequalities along the Texas-Mexico borderlands, and has even contributed to discourse over American citizenship (Paredez, 2009). In addition, in the context of the United States her memory, as seen in Figure 2, has contributed to the formation of latinidad—or what it means to be a Latina (Paredez, 2009). Guacardo’s representations of the beloved singer contribute to the embodied acts of commemoration that have helped Latina Americans articulate their own identity and helps illustrate an image of what a Latino American identity may look like.

Cross-Platform Socials and Shared Experiences

With various levels of popularity and impact across platforms, mitú’s social media presence is a critical and interesting component of the brand’s overall discourse. Platforms like Snapchat, Instagram and Facebook connect readers directly with mitú’s news content, as it is embedded and hyperlinked in various ways to take advantage of each platform’s affordances. However, most importantly is that its social media content goes beyond just communicating the news. Each platform provides mitú with a way of engaging its target audience through culturally relevant content such as videos, parodies, comedic skits, animations and memes. Increasingly the connection between news content and that of entertainment is being made across mitú’s social media platforms, working together to construct characteristics of a Latino American identity and informing this audience about issues relevant to their community.

Although the discourse on each platform appears to be distinct, with a unique composition of content, collectively they share much of the same content that is cross-posted as well as many of the same characteristics. Looking at intertextual cues used in many of the posts, it can be seen that mitú’s social media discourse borrows heavily from both American and Latin American entertainment media, which is bilingual in nature. It makes reference to famous Latino icons, as well as contemporary allusions to American pop culture, and often it finds ways to combine the two. The functional outcome of this tactic is to create nostalgia for childhood, breakdown individual differences, and emphasize shared experiences amongst Latino Americans. The broader significance is that this approach articulates a distinct Latino American culture that is at once unique, but also hybridized because of its influences from American and Latin American media.

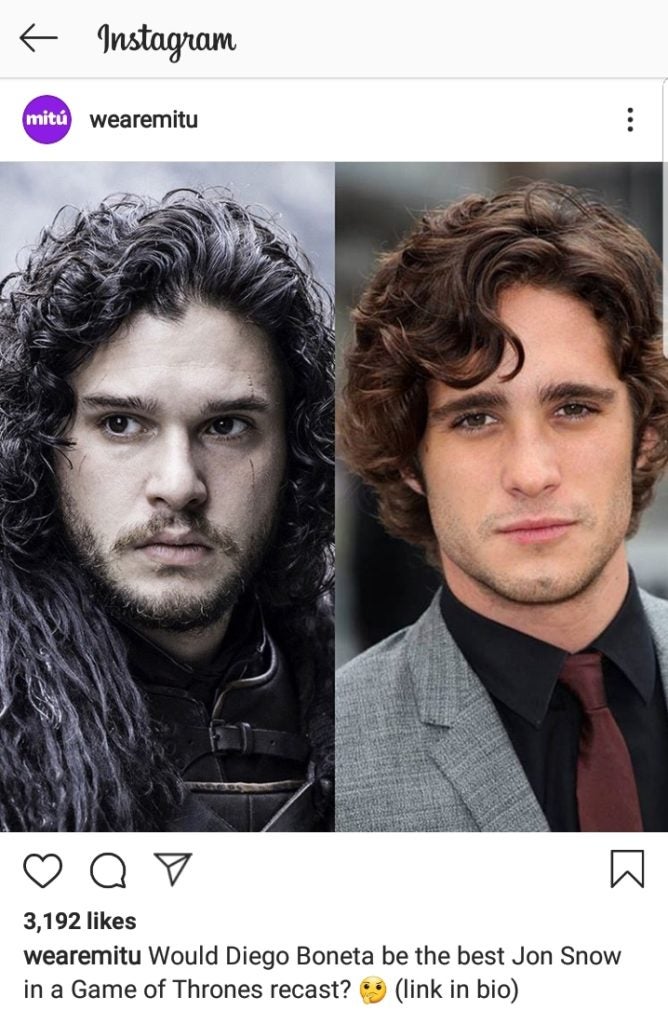

This articulation of Latino American identity through social media can most notably be seen by discourse surrounding three central topics—celebrity, comedy, and food. While celebrity representation on mitú’s social media pages occasionally incorporate American celebrities of different ethnic/racial backgrounds than its core audience, often the celebrities that are highlighted are Latinos of various races and nationalities. Rather than focusing on the exceptionalism of these individuals, their celebrity is used to connect various aspects of identity such as shared national origins, to contribute to a uniform Latino American culture. Celebrities illustrate the vast presence that Latinos have in American and global entertainment industries, and where Latinos are not found, mitú creates counternarratives as to where these industries could incorporate more Latinos and celebrities of color. By “recasting” famous movie and television characters with Latinos, as seen in Figure 3, mitú creates a space for conceptualizing Latino American identity as being deeply embedded into the broader United States mainstream culture—rather than that of a minority group.

As seen through the creation of its mascot Guacardo, and viral videos of competitive abuelas, comedy plays an important role in mitú’s social media presence. Again, borrowing on sociocultural and intertextual cues from shared experiences and entertainment media, the comedic point-of-view that is created highlights the characteristics of the identity that mitú is constructing. Much of the comedy builds on both jokes in Spanish and in English. The two languages are often combined in a way that illustrates a generational divide—where the voice of family (i.e. mother or abuela) is in Spanish, but the voice of the youth is in English. Food serves as another anchoring concept of shared identity, but also of diversity. As each Latin American region has developed its own unique cuisines, and this culinary heritage has led to many different types of translations in the United States, mitú highlights this diversity through their posts and culture articles to illustrate the ways in which Latino American food can reflect other intersectional characteristics of a family’s identity. One example, highlighting 21 different variations on Sopa de Fideo, was particularly significant for this author as it emphasized how a seemingly simple childhood staple was shared by many others throughout the United States and Latin America (Mitú Staff, 2018). So while variations may highlight diversity, mitú is shaping a broader Latino American identity by emphasizing shared experiences and culture amongst audiences—without essentializing Latinos into one homogenous group.

By creating content that can easily be shared, such as memes and funny videos, mitú is not only constructing a cogent notion of Latino American identity for young audiences, but is also providing them with a way to articulate individual identities and experiences themselves. Memes, for example, provide Latino Americans with content that is in a format familiar to non-Latinos, which allows them to share memes with their broader social networks online. Additionally, being on various platforms that each engage with different demographic groups, mitú is opening the door for cross-generational flows of content so that youth audiences can also connect with older members of this cultural group. As important cultural markers for the creation of a shared identity, social media content serves not only to entertain, but also to engage audiences. And through intertextual cues and shared cultural values, social media content is allowing mitú to craft news discourse that is more relevant and significant to Latino American audiences.

Challenging Ideological Notions Through News

As a form of Latino journalism, mitú’s journalistic discourse is unique in its approach to everyday topics—varying not only in its selection of newsworthy events but also in its framing of the news. Although the publication serves many of the same roles that traditional legacy news media have established, as a digital native publication mitú pushes the boundaries of American journalism and deconstructs many of the established norms and routines. For this reason, analysis of mitú’s website allowed for a better understanding of RQ2 (How does mitú’s discourse challenge patriarchy and other ideological notions of hegemony?). By establishing new categories of news that are culturally relevant and highlighting the significance of particular types of news stories, mitú not only speaks to a Latino American audience, but also actively shapes the identity of what this audience can be. The four major sections of news on mitú’s website are: Entertainment, Things That Matter, Culture and Fierce. Continuing the thread of its social media discourse, much of the news that mitú creates emphasizes shared experiences, interests and cultural ties amongst Latinos. But unlike other content in legacy news media, mitú directly confronts ideological factors that have contributed to sociocultural inequality for Latino Americans and even those that stem within this group. By naming ideologies and giving a voice to injustices that seek to divide groups along hegemonic notions of masculinity or white supremacy, mitú is able to speak to many of the intersectional characteristics that contribute to Latino American diversity—creating a space for simultaneity and acknowledging the diverse racial, cultural and gendered aspects of this heterogeneous audience.

FIERCE Articles and New Conceptions of Identity

As one of four key categories on mitú’s website, described as a collection of content that is specifically created for the empowerment of Latinas, FIERCE represents a unique set of news that touches on the gendered aspects of Latino American identity. Through this collection, several important ideological conversations emerge—colorism/pigmentocracy, machismo, and LGBTQ+/Queer identity. This centrality of ideological issues can be seen in a recent article titled “You Can Thank Machismo For Our Dying Planet, Here’s Why,” where notions of machismo and hegemonic masculinity are negatively associated with the decline of some sustainable practices (Reichard, 2019). Connecting these ideologies back to recent research, which found that environmentally-friendly practices like recycling are considered “feminine,” mitú’s journalists highlight the significance of embracing non-binary notions of gender identity to improve sociocultural practices in the future. Another article that placed ideological issues at the forefront is titled “Cardi B’s Favorite Brand Fashion Nova Is In A Whole Lot Of Boiling Hot Water After A Model Accused Them Of Colorism” (Reindl, 2019a). As suggested in the headline, this article tackled the notion of colorism and white supremacy of clothing brand Fashion Nova because of its choices in models and disjointed media strategy. By bringing these issues to light, mitú’s journalists are engaging their readers in deeper conversations about sociocultural dynamics, hierarchies, and how characteristics of their individual identities may intersect with concepts. By identifying and placing a central focus on ideological values, mitú is providing its audience with the language necessary to articulate their own experiences and actively question how these deeply engrained ideologies take shape in other aspects of their lives.

Constructing New CULTURE

Although distinct from the articles in the FIERCE category, in that they do not solely focus on Latinas, CULTURE provides a similar emphasis on intersectional characteristics of Latino American identity and how these are articulated through Latino culture. From sharing traditional recipes from an abuela to shared experiences, this category of articles illustrates what it’s like to live in the Latino American community and the diverse factors that contribute to this identity. While the journalistic discourse in this category is diverse, tackling everyday topics of food and family dynamics, it also provides a platform for discussing social inequalities, cultural appropriation and hegemony. In particular, CULTURE articles are creating a counternarrative to that of machismo and hegemonic masculinity to discuss how new generations are combatting violence and inequalities against women and the LGBTQ+ community. Articles like “Ya Basta Con El Toxic Machismo That Has Caused Violence Against Women And The LGBTQ+ Community” touch on this topic of systemic machismo, allowing mitú’s own journalist to reflexively consider their own positionality in the conversation (Thompson-Hernandez, 2017). This article, like mitú’s others on this topic, discussed the social construction of masculinity and how this can affect young boys within the community. Additionally, mitú’s journalists gave a voice to 12 Latinos of diverse intersectional characteristics (in terms of gender identity, race, color and orientation) as they shared their own opinions on how to “undo patriarchal ways of thinking” and deconstruct hegemonic notions of masculinity (Thompson-Hernandez, 2017, para. 9).

Aside from creating a counternarrative against machismo, mitú’s journalists are actively contributing to this discourse by highlighting stories that go against hegemonic notions of masculinity. This is most clearly illustrated by a recent article titled “These Men Represented Their Country In The Mister Global Pageant And We Are Living For These ‘National Costumes’,” in which the main focus was something considered feminine—a beauty pageant (Lessner, 2019). This international pageant, however, was specifically geared towards men who represented nations from all over the world. The discourse of this article framed the men as “inspirational role models” (Lessner, 2019, para. 6). And although a Latino didn’t win Mister Global in 2019, their participation in the contest sparked significant conversation on culture. Not only did this article highlight the significance of thinking outside of a gender binary, but it also raised the question of racial/ethnic identity and the vast diversity of Latino populations. A particular focal point of the article was the competition’s “National Costume Show—a segment designed to showcase clothing that honors and celebrates contestants’ home countries” (Lessner, 2019, para. 1). Adorned in traditional cloth, feathers, gold and stones, Latinos from each nation paid tribute to the diverse indigenous peoples of their nation, often channeling tribal groups that were eradicated by the Spanish colonization of North and South America. Their representations not only highlighted the rich cultural identity of Latinos, but also spoke to the ways in which characteristics that were once seen as feminine or subordinate can now have significant impacts in global discourse about identity.

Emphasizing a U.S. Context with THINGS THAT MATTER

Of all the categories created by mitú, none is quite as informative as the THINGS THAT MATTER. As noted in the category’s name, THINGS THAT MATTER highlights news that are particularly significant and relevant to a young Latino American audience. And through its coverage of recent events, THINGS THAT MATTER anchors mitú’s journalistic discourse to a U.S. point-of-view. Ranging from the political to the sociocultural, the topics covered in this category are diverse but ultimately always connect back to Americans or the United States. Although these articles focus the perspective that the publication presents, by dictating what issues and topics should be important to their audience, ultimately they contribute to a uniquely American point-of-view. And furthermore, to the representation of how Latino Americans fit into the broader hierarchies of power. Still, even while emphasizing a particular U.S. context, mitú is able to tackle significant topics such as immigration from the global South and violence against the Latino diaspora. Articles like “The Smithsonian Is Preserving A Part Of Our Most Shameful History By Exhibiting Drawings From Children In Cages” touch on a variety of these aspects, including Latino Americans’ connections with migrant communities, their moral values, these individuals’ positionality within the United States, and how Latino Americans can keep U.S. offices of power accountable for their actions (Cruz Gonzales, 2019).

This new THINGS THAT MATTER category also incorporates articles that would traditionally fall under the categories of: News, Politics, Features, Economics and more. However, by incorporating these various topics into one new category, mitú’s journalists are not only able to talk about intersectional characteristics of Latino American identity, but also about the intersectional characteristics of the news. Articles are able to touch on politics, other sociocultural influences, and economics in one large conversation. And though this can complicate the process of reporting, it allows for more complex questions to be raised and more diverse conversations to take place. Articles like “Gina Torres, The Mother Queen, Says ‘Afro-Latinos don’t fit into a box, they fit into all the boxes’” allow for the diversity of Latino American identity to come into question and illustrates the ways in which this identity is articulated in a sociocultural context—Hollywood and entertainment media (Reindl, 2019b). Additionally, they question patriarchy, white supremacy and social inequities directly, challenging the status quo. Through the experiences of strong celebrities like Gina Torres, articles like these in THINGS THAT MATTER not only describe the experiences of Latino Americans with various intersectional characteristics but also describe a path forward for a better future for all.

Conclusions

In analyzing mitú’s discourse across their various social media platforms and website, this study found that mitú is able to engage audiences and provide a Latino point-of-view for their content through various symbol systems—including two linguistic systems (Spanish and English) and various types of media (e.g. telenovelas). Highlighting the intersectional characteristics that contribute to the diversity of their audience, mitú rearticulates the differences once associated with individual nationalities and races to construct a new type of Latino American identity that unifies rather than fragments. In the process of constructing this identity, mitú’s journalism and entertainment content directly confront hegemonic ideologies that have contributed to sociocultural inequality for Latino Americans. Diverging from traditional legacy news media in their approach to topics like white supremacy, hegemonic masculinity and their counterparts in the Latino community (e.g. colorism and machismo), mitú names these ideologies and challenges them to create space for simultaneity in Latino American identity and acknowledge the vast diversity of their audience.

Although the specific nature of mitú’s journalistic discourse contributes significantly to counternarratives against ideologies like patriarchy and to the construction of a Latino American identity, there are significant limitations to the publication’s approach. In particular, these limitations take shape in the form of a particular type of identity, the deconstruction of certain ideological values in lieu of others, and a unique interpretation of journalistic values.

Most obvious is the specificity of the Latino American identity that is created by mitú’s social media and journalistic discourse. With significant discourse around national identities and their contributions to a collective Latino identity, mitú focuses on immigration and shared experiences through the perspective of second or third generation Americans. Although much of the content is in a mixture of Spanish and English, mitú takes for granted that not all Latino Americans grow up with the Spanish language as part of their home. Because Spanish terms and allusions are embedded in their humor and the nuances of its storytelling, the shared experiences that mitú often refers to may not be something that newer generations may have. Much of this is particularly mediated by focusing on a young, primarily Millennial audience. However, it ignores the realities lived by many Latinos whose families may have been in the United States for three-plus generations and have assimilated to larger American sociocultural trends. Additionally, as their references often extend beyond recent events, to shared experiences and media of the past, they often touch on telenovelas, music, and Spanish-language news in a way that assumes multicultural media consumption. Beyond the barrier of language, this assumed access to diverse media content means that the Latino American identity created not only assumes particular cultural ties, but also a particular socioeconomic class.

The particular way in which this Latino American identity is articulated is even further defined by mitú’s approach in tackling ideologies. By questioning ideological values like machismo and colorism, as well as their sociocultural manifestations in the United States, mitú’s discourse on many of its topics are conveyed through a progressive and liberal angle. Mitú challenges notions like patriarchy, hegemonic masculinity and white supremacy through its coverage on important topics like immigration and Latino representation. But at the same time, mitú is coding other ideological beliefs into its Latino American identity. In particular, this can easily be seen in its coverage of immigration, politics and the Trump presidency. While acknowledging the diversity of Latino Americans’ political beliefs, sociocultural binaries are emphasized in what it means to identify as a Latino American (Danielli, 2019). This, for example, is articulated in a pro-immigration stance. In a recent article about a Republican politician who was formerly an undocumented immigrant, pointed language illustrated this point-of-view when one of mitú’s journalists said that “Whittney Williams, a young Taiwanese Republican … is happy to throw Latinxs under the bus or into alligator-infested moats to score political points with a racist constituency that likely would never vote for an Asian American” (Pellot, 2019, para. 1). Even though Williams does not identify as a Latina American, this article illustrates the ways in which particular intersectional characteristics are not fully recognized as contributing to individual beliefs, and instead focuses on broader political ideologies that are coded into Latino American identity.

Multiplicity of mitú’s Discourse

While mitú is actively constructing the social identity of what it means to be a Latino American, the publication is also not fully conforming to another social identity—that of American journalism. By not adhering to the professional identity of American journalists or many of the well-established values (i.e. fairness, balance, and objectivity), mitú’s coverage is markedly different than that of legacy news media. Many stories are secondary reporting and often author bias has a significant voice in the narrative. And while critical perspectives may help galvanize a community of like-minded individuals, it illustrates a potentially dangerous precipice for a future snowball effect. As American journalism is currently dealing with conversations of partisan bias, echo chambers and the possibility of sharing misinformation, deviation from well-established values can leave mitú’s journalistic discourse open to criticism. In addition, it could also contribute to significant sociocultural ramifications if Latino Americans are only being well-informed on a narrow set of issues, through a particular ideological lens.

Collectively, mitú’s discourse is a particularly interesting object of analysis because of its diverse characteristics and its central value of constructing a Latino American identity. Its direct confrontation with hegemony and ideologies, which have historically repressed this group’s representation in broader journalistic discourse, brings Latino voices to the forefront of U.S. news and social media. At the same time, it connects a diverse audience into a cogent identity group, whose intersectional characteristics are embraced as a part what it means to be Latino American. But there are also challenges that lie ahead, as mitú not only defines its audience but also seeks to inform a growing portion of the American electorate. As a qualitative survey of mitú’s news and social media content, this study is limited in that its analysis provides broad strokes for understanding mitú’s collective discourse—identifying patterns in the style, structure and content of mitú’s various multimedia products. Although various particular examples are used to illustrate patterns that emerged during analysis of this cross-platform corpus, further investigation is needed to better understand the composition of mitú’s audience, how mitú is using various media platforms for their particular affordances, and how mitú’s networks intersect with various other publications and communities online. Future studies should analyze mitú’s content to further understand the publication’s unique news values, what roles it serves for a Latino American audience, and how the publication will articulate Latino American identity for future generations.

References

Acevedo, B., & Beniflah, J. (2018, March 1). An interview with Beatriz Acevedo [Text]. Retrieved from https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/hsp/ jcms/2018/00000003/00000001/art00002

Azmitia, M., & Thomas, V. (2015). Intersectionality and the development of self and identity. Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences: An Interdisciplinary, Searchable, and Linkable Resource, 1–9. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9781118900772.etrds0193

Bonilla-Silva, E. (2002). We are all Americans!: The Latin Americanization of racial stratification in the USA. Race and Society, 5(1), 3–16.

Broersma, M. (2010). Journalism as performative discourse. In V. Rupar (Ed.), Journalism and Meaning-Making Reading the Newspaper, 15–35. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Cauce, A. M., & Domenech-Rodriguez, M. (2002). Latino families: Myths and realities. In J. M. Grau (Ed.), Latino Children and Families in the United States: Current Research and Future Directions, 3–25. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers.

Chalaby, J. K. (1996). Journalism as an Anglo-American invention: A comparison of the development of French and Anglo-American journalism, 1830s-1920s. European Journal of Communication, 11(3), 303–326.

Citrin, J., Wong, C., & Duff, B. (2001). The meaning of American national identity. Social Identity, Intergroup Conflict, and Conflict Reduction, 3, 71.

Cruz, A. (2019, May 15). #YouKnowMe Is the viral hashtag Latinas are using to tell their freeing abortion stories after Alabama lawmakers passed one of the most extreme abortion bans in the country. We Are Mitú. Retrieved from https:// wearemitu.com/fierce/latinas-share-their-abortion-story-in-wake-of-abortion-ban-in-alabama/

Cruz Gonzales, M. (2019, July 15). The Smithsonian is preserving a part of our most shameful history by exhibiting drawings from children in cages. We Are Mitú. Retrieved from https://wearemitu.com/things-that-matter/the-smithsonians-interest-in-detained-childrens-drawings-draws-criticism/

Danielli. (2019, October 3). This study on Latino Republicans and their beliefs will make you better understand your MAGA family. We Are Mitú. Retrieved from https:// wearemitu.com/things-that-matter/latino-republicans-houston-study/

Delgado, R., & Stefancic, J. (2017). Critical race theory: An introduction (Vol. 20). New York, NY: NYU Press.

Fairclough, N. (2013). Critical discourse analysis: The critical study of language. New York, NY: Routledge.

Fenton, N. (2009). News in the digital age. In S. Allan (Ed.), The Routledge companion to news and journalism (pp. 601–611). New York, NY: Routledge.

Fenton, N. (2010). New media, old news: Journalism and democracy in the digital age. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Gómez, C. (2000). The continual significance of skin color: An exploratory study of Latinos in the Northeast. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 22(1), 94–103.

Graham, J. (2016, January 13). Latino digital network Mitu raises $27 million. USA TODAY. Retrieved from https://www.usatoday.com/story/tech/2016/01/13/latino-digital-network-mitu-raises-27-million/78711134/

Holvino, E. (2010). Intersections: The simultaneity of race, gender and class in organization studies. Gender, Work & Organization, 17(3), 248–277. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2008.00400.x

Holvino, E. (2012). The ‘simultaneity’ of identities. In C. Wijeyesinghe & B. W. Jackson (Eds.), New Perspectives on Racial Identity Development: Integrating Emerging Frameworks, 161–191. New York, NY: NYU Press.

Lazar, M. M. (2014). Feminist critical discourse analysis. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Online Library.

Lazarte-Morales, A. (2008). Ethnic journalism. The International Encyclopedia of Communication. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Online Library.

Lessner, J. (2019, October 7). These men represented their country in the Mister Global Pageant and we are living for these ‘national costumes.’ We Are Mitú. Retrieved from https://wearemitu.com/culture/these-men-represented-their-country-in-the-mister-global-pageant-and-we-are-living-for-these-national-costumes/

Manago, A. M. (2015). Identity development in the digital age. The Oxford Handbook of Identity Development. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199936564.013.031

Mitú Staff. (2018, February 1). These 21 ways of enjoying sopa de fideo are delicious, surprising, and very different. We Are Mitú. Retrieved from https://wearemitu.com/culture/food-and-drink/these-21-ways-of-enjoying-sopa-de-fideo-are-delicious-surprising-and-very-different/

Paredez, D. (2009). Selenidad: Selena, Latinos, and the performance of memory. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Pellot, E. (2019, October 3). She is a former undocumented immigrant and now she’s running for Congress as a Republican who wants to build Trump’s wall. We Are Mitú. Retrieved from https://wearemitu.com/things-that-matter/this-formerly-undocumented-immigrant-wants-to-help-trump-build-his-wall/

Pew. (2014). Key takeaways from the Pew Research survey on Millennials. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/03/07/6-new-findings-about-millennials/

Pew. (2018a). Millennials expected to outnumber Boomers in 2019. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/03/01/millennials-overtake-baby-boomers/

Pew. (2018b, October 25). Many Latinos blame Trump administration for worsening situation of Hispanics. Pew Research Center’s Hispanic Trends Project. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2018/10/25/more-latinos-have-serious-concerns-about-their-place-in-america-under-trump/

Rampersad, R. (2012). Interrogating pigmentocracy: The intersections of race and social class in the primary education of Afro-Trinidadian boys: Ravi Rampersad. In K. Bhopal & J. Preston (Eds.), Intersectionality and race in education (pp. 65–83). New York, NY: Routledge.

Reichard, R. (2019, March 25). You can thank machismo for our dying planet, here’s why. We Are Mitú. Retrieved from https://wearemitu.com/fierce/study-men-would-rather-ruin-our-planet-than-appear-feminine/

Reindl, A. (2019a, July 24). Cardi B’s favorite brand Fashion Nova is in a whole lot of boiling hot water after a model accused them of colorism. We Are Mitú. Retrieved from https://wearemitu.com/fierce/black-model-atim-ojera-exposes-more-of-fashion-novas-colorist-business-practices/

Reindl, A. (2019b, July 26). Gina Torres, the Mother Queen, says ‘Afro-Latinos don’t fit into a box, they fit into all the boxes.’ We Are Mitú. Retrieved from https://wearemitu.com/things-that-matter/gina-torres-talks-imposter-syndrome/

Renn, K. A. (2012). Creating and re-creating race: The emergence of racial identity as a critical element in psychological, sociological, and ecological perspectives on human development. New Perspectives on Racial Identity Development: Integrating Emerging Frameworks, 2, 11–32.

Rockquemore, K. A., & Arend, P. (2002). Opting for white: Choice, fluidity and racial identity construction in post civil-rights America. Race and Society, 5(1), 49–64.

Rodriguez, A. (1999). Making Latino news: Race, language, class (Vol. 1). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Thompson-Hernandez, W. (2017, September 22). Ya basta con el toxic machismo that has caused violence against women and the LGBTQ+ community. We Are Mitú. Retrieved from https://wearemitu.com/bad-hombres/12-latinos-open-up-about-toxic-machismo/

Van Dijk, T. A. (2009). News, discourse, and ideology. In K. Wahl-Jorgensen & T. Hanitzsch (Eds.), The Handbook of Journalism Studies, 191–204. New York, NY: Routledge.

Van Dijk, T. A. (2013). News as discourse. Hillsdale, NJ: Routledge.

Wahl-Jorgensen, K., & Hanitzsch, T. (2009). The handbook of journalism studies. New York, NY: Routledge.

We Are Mitu. (2019). About mitú. We Are Mitú. Retrieved from https://wearemitu.com/about-mitu/

Wodak, R., & Fairclough, N. (2013). Critical discourse analysis. London, England: Sage.

Wu, L. (2016). Did you get the buzz? Are digital native media becoming mainstream? ISOJ Journal, 6(1), 131–149.

Ryan Wallace is an interdisciplinary researcher whose background includes the life, physical and social sciences. In 2013, he began his career with a Bachelor of Science in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology from the University of California, Irvine. Working as a science journalist and grant writer, his unique ability to effectively communicate science sparked a career in media and a keen interest in how science is portrayed to mass audiences. In 2017, he received an MS in Biotechnology from Cal State University, San Marcos. He then transitioned into the social sciences, studying science communications and journalism at the University of Texas at Austin for his Ph.D. Currently his research centers around mediated science communications with a particular focus on key issues such as the Anthropocene, new media, and development in Latin America. Wallace analyzes discourse to better understand the polarization of these topics, how various stakeholders are engaging in these complex conversations, and the role that media play in shaping perceptions of scientific discourse.