April 23, 2017 | International

Pre-ISOJ seminar tackles issues facing journalists reporting on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border

Journalists from both sides of the border tackled modernization, fake news and corruption during the Bridging the Border seminar the day before the International Symposium on Online Journalism (ISOJ) on Thursday, April 20.

Kicking off the seminar was keynote speaker and Dallas Morning News Managing Editor Robyn Tomlin who spoke to many of the changes the paper went through over the past two years in her speech “Rock of Truth 2.0: What’s old is new again.” One of those major changes was an attempt to connect more with the Hispanic community and also to be more transparent with their readers.

In terms of transparency, the Morning News invited some of their critics to sit in on one of their meetings to better understand how the paper is put together.

“Our goal is to be more transparent overall … being willing to face your critics is an important part of transparency,” Tomlin said. “I don’t know that we changed those guys minds when we brought them into the newsroom, but we changed their perspectives.”

The Morning News also has full time immigration and Texas/Mexico border and also offers weekly Spanish classes in the newsroom.

“We really think it’s important that as many journalists as possible are able to bridge that gap and cover a community that’s typically been underreported,” Tomlin said.

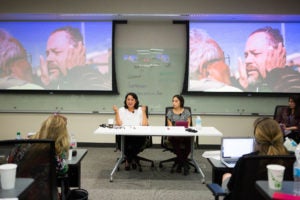

In order to better bridge the gap in coverage, journalists Joy Díaz, Texas Standard producer for KUT in Austin, and Rocio Guenther, reporter at the Rivard Report in San Antonio spoke to the importance of knowing more than one language for their panel on “Serving and covering the Latino community in the U.S.”

Díaz encouraged people to become bilingual or trilingual in order to better understand the issues that face communities where English isn’t the main language.

“The stories, the immigrant stories, the stories of our parents, the stories that we live and we are able to report on would not be possible or would not be as easy to report if we only spoke one language,” Díaz said. “It is very important for the authenticity of our report to be heard from the people who are going through that experience.”

Guenther seconded her point by adding that oftentimes, in her work, she finds subjects who are reluctant to speak, begin to open up once she speaks to them in Spanish.

“There’s this paranoia right now, especially in the Latino community, and people are very afraid to tell their stories,” Guenther said. “They’re very afraid to open up, but the moment they hear me speak Spanish it’s like the walls come down.”

Emily Ramshaw, editor-in-chief of the Texas Tribune, and Adela Navarro Bello, director of Zeta magazine in Tijuana, discussed “Covering politics in the era of #FakeNews and #AlternativeFacts.”

From the start of the panel, Ramshaw was quick to concede that one of the biggest failings of the media in covering the 2016 election was not listening to their audience.

“We really were out of touch with a lot of our readers,”Ramshaw said. “I think that there’s a lot of soul searching happening in newsrooms around the United States right now about how we better understand the public, how the media largely missed the mark in the outcome of the general election, and what we need to do to better understand and inform people across this nation.”

Navarro began her presentation explaining the dangers of journalism in Mexico where eleven reporters were killed in 2016. In its history, Zeta has not been exempt from this violence. In 37 years of stories, two of its publishers have been murdered, they’ve received countless threats, and Navarro has had to live with protection for a decade.

However, the director said that it is precisely because of this context in which “three carteles” are pressuring journalism – government, drug trafficking and organized crime – that makes it necessary to continue the journalistic investigation.

“We do it because we have the commitment to do investigative journalism, a commitment to society, to Mexicans and we want help this with justice, to [fight] against impunity, we want to tell society that not everything is lost,” Navarro said.

This attitude has worked for them. At Zeta, they feel that their readers are very close, in fact, she said 60 percent of its content comes from proposals from society. They are convinced that their goal is to be “close to society and away from the Government”.

And to achieve this, like most media, when it comes to research the key is to be skeptical of information, and that’s what Navarro tells her reporters.

“[I’m telling them] be skeptical, do not believe what the government says, we’re going to prove what the government is saying,” Navarro said. “The way to unmask a government is by doing investigative journalism.”

One tool that was created to help journalists expose corruption and cover violence is MexicoLeaks, an anonymous whistleblower site similar to WikiLeaks. Celia Guerrero, journalist at Pie de Pagina, which has used MexicoLeaks in some of its reporting, said the tool is an important way for journalists to gather their resources and collaborate with international colleagues to take down corrupt governments.

“We could be collaborating more with our colleagues in the United States to find out who these groups are and who they’re connected to,” Guerrero said. “The technology is there. We’re digital journalists, we have the access and the technology to be corresponding and we should be doing that.”

Guerrero spoke on the panel “Stories from the border” with multimedia journalist Alicia Fernández from newspaper El Diario de Juárez.

Fernández gave a bit of advice in terms of covering the victims of the corruption and violence they work to expose in order to avoid being insensitive or re-victimizing them.

“It’s really important to be focused on why you really want to tell the story,” Fernández said. “You need to have a lot of sensitivity and empathy and think about [their situation] as something that could happen to anyone […] in order to create a space for them where they feel confident that they can talk to you.”

To close the seminar, reporter Anabel Hernández spoke about the challenges she faced during her two year investigation of the 2014 Iguala kidnapping in which 43 male students from the Ayotzinapa Rural Teachers’ College went missing in Iguala, Mexico. Her findings were released in her book “La Verdadera Noche de Iguala” and in various articles in magazine Proceso.

For her talk, “Investigating corruption (and protecting yourself) as an independent journalist,” Hernández told how she traveled to Iguala several times a month for two years, interviewing the surviving students of the incident and challenging the government to uphold its transparency law in order to get access to certain documents that pertained to the case.

At the end of her investigation, she found that the disappeared students were unknowingly on buses that were carrying $2 million worth of heroin. According to the official account, the students were taken by crime syndicate Guerreros Unidos, killed, incinerated, and had their remains thrown into the San Juan River. Supposedly backing up this official account is a bone fragment of one of the students found on the banks of the river, though several forensic experts question how possible this is.

Despite her findings, Hernández knows it won’t ever be acknowledged as the official account.

“At the end of my investigation I found that the attorney general’s office recognized that [the students] weren’t buried at the Rio San Juan and they planted those bones that were found,” Hernandez said. “The government will never, ever move away from that explanation.”

Bridging the Border: Digital perspectives from women journalists in Texas and Mexico was held at the School of Journalism at the Moody College of Communication on the campus of the University of Texas at Austin on April 20, 2017. Video from the event is available here.