Journalism: How One University Used Virtual Worlds to Tell True Stories

By Leonard Witt, Farooq A. Kperogi, Gwenette Writer Sinclair, Claire Bohrer and Solomon Negash

This case study demonstrates a relatively low-cost, quick-startup project that advances work in virtual world immersive journalism; in this case, to amplify the voices of often marginalized youth in the juvenile and criminal justice systems. Using ethnographic and survey research, it provides insights into producing “machinimas” (videos filmed in virtual worlds) to tell journalistic stories using virtual world tools, props, scenery and avatars, and provides a prototype for college-level journalism, communication and media studies programs considering initiating their own immersive journalism and virtual reality journeys.

Introduction

This paper developed from a grant-funded, university-based project that emulated, at least in part, the work of Nonny de la Peña. The research team uses her definition of immersive journalism as a touchstone: “[The] production of news in a form in which people can gain first-person experiences of the events or situations described in news stories” (de la Peña, et al., 2010, p. 291). Our research uses a combination of ethnographic and survey research methods. It is written from the perspectives of the project leaders: a journalism professor who was the Principal Investigator, a virtual world development expert who oversaw the creation of the virtual world and machinimas, one of the 11 student interns, an app developer and an online journalism researcher. The professor, the virtual world expert, and the intern have borrowed from the autoethnography qualitative research toolkit in writing their individual sections. The approach “acknowledges and accommodates subjectivity, emotionality, and the researcher’s influence on research…” (Ellis, 2011, Section 1, para 3). The paper aims to inform journalism, communication and media studies programs in deciding if they should be offering immersive journalism courses or developing immersive journalism curriculum and virtual reality labs or centers.

Virtual Worlds and Immersive Journalism — An Overview

The temporal co-occurrence of immersion and interactivity is the essence of virtual reality. As Burdea and Coiffet (2003) point out, virtual reality is neither exclusively telepresence nor augmented reality nor, for that matter, any particular hardware. It is “a simulation in which computer graphics are used to create a realistic-looking world [where] the synthetic world is not static, but responds to the user’s input (gesture, verbal command, etc.). This defines a key feature of virtual reality, which is real-timeinteractivity. Here real time means the computer is able to detect an input and modify the virtual world instantaneously” (p. 2, emphasis original). Immersive journalism enables participants to have an embodied experience of actually entering “a virtually re-created scenario representing the news story… typically represented in the form of a digital avatar, an animated 3D digital representation of the participant, and see the world from the first-person perspective of that avatar” (de la Peña, et al., 2010, p. 292).

As Raney Aronson-Rath, James Milward, Taylor Owen and Fergus Pitt (2016) point out, immersive journalism draws extensively from social presence theory, which argued that, in spite of popular notions to the contrary, interlocutors in mediated online discourses can project social cues that inspire social presence in their dialogic enterprise (Short, Williams, & Christie, 1976). Short, Williams and Christie (1976) showed that social presence theory has two interconnected parts: intimacy and immediacy. Immersive journalism expands on these notions. The possibilities of what some scholars have called avatar anthropomorphism (Lugrin, Latt, & Latoschick, 2015) and the illusions of place, plausibility, and body ownership that are possible in virtual reality provide the basis for and growing popularity of immersive journalism.

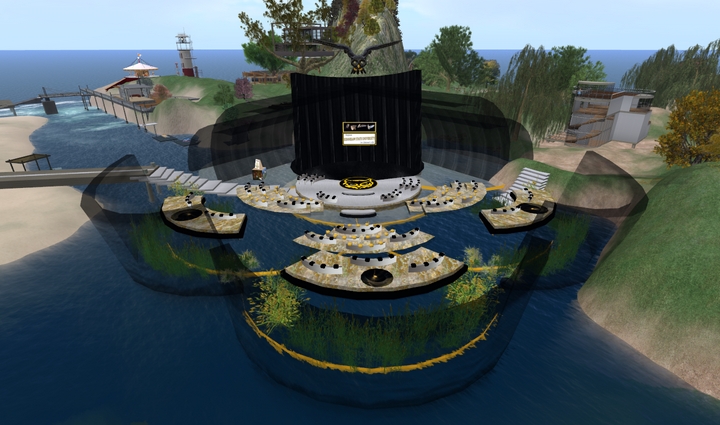

Virtual reality journalism first materialized about the mid-2000s, practiced primarily in Second Life, a user-created, 3D virtual world. It featured weekly news shows like Metanomics with host Robert Bloomfield, professor of accounting at Cornell University (Figure 1). Metanomics was an audience-interactive interview show premiering in 2006, coterminous with a spike in Second Life’s popularity after sustained traditional and digital media coverage of its activities (Totila, 2007). Metanomics was described as “the seminal form of what journalism will look like in the 21st century” (Cruz & Fernandes, 2011, p. 6).

Figure 1. Metanomics news show. Weekly virtual world news show with host, Robert Bloomfield. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2BzQwVy1yCc (Academic Fair Use).

Previous experiments in virtual reality journalism and virtual world storytelling did not involve the participant in as much perceptual and corporeal investment as immersive journalism does, a reason de la Peña and her colleagues distinguished between “interactive journalism or low-level immersive journalism” and “deep immersive journalism” (de la Peña, 2010, p. 299). Deep immersive journalism invites greater, deeper, and more extensive spatial, temporal, and corporeal involvement in the reliving of re-created news events in the virtual world. This notion of immersion is consistent with Biocca and Delaney’s (1995) definition of virtual reality immersion as the “degree to which a virtual environment submerges the perceptual system of the user in computer-generated stimuli. The more the system captivates the sense and blocks out stimuli from the physical world, the more the system is considered immersive” (p. 57). This is made possible by a concatenation of three interrelated illusory sensations—the illusions of place, plausibility, and body ownership—that predispose participants to feel that they are in a real place, reliving real stories, with real bodies, which can activate a sensation known as response-as-if-real, also called RAIR (de la Peña, et al., 2010). If the medium was the message in traditional journalism, the audience is the message in the emergent immersive journalism model since it is “defined by the relation between journalism and its audience, rather than on its relation to the medium it uses for communicating with the audience” (Latar & Nordfors, 2009, p. 23).

Avatar-driven virtual worlds already have a massive audience base; Second Life maintains an audience of 900,000 active users monthly (Weinberger, 2015). Piper Jaffray Investment Research predicts that “virtual reality and augmented reality are the next mega tech themes through 2030. We liken the state of virtual and augmented reality today as similar to the state of mobile phones 15 years ago” (Munster, Jakel, Clinton, & Murphy, 2015, p. 1).

A keyword in virtual worlds and VR is empathy. Chris Milk (2015), founder and CEO of virtual reality company Vrse, calls virtual reality “the ultimate empathy machine” (2:28) that “connects humans to other humans in a profound way … we become more compassionate, we become more empathetic, and we become more connected and ultimately we become more human” (9:57).

At the 2012 Sundance Film Festival, watching de la Peña’s immersive journalism piece,Hunger in Los Angeles, the audience virtually stood in a food line where a man suddenly falls to seizures on the ground in front of them. “Audience members tr[ied] to touch non-existent characters and many cried at the conclusion of the piece” (Immersive Journalism, 2012, para. 3). Increasingly, traditional news organizations like the Des Moines Register, USA Today, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, ABC, CNN, The Associated Press, and Vice have started immersive journalistic complements to their regular news stories (Brustein, 2014; Manly, 2015).

However, although immersive journalism in the virtual world has been on a steady rise in the past decade, there has been little scholarly interrogation of its singularities, potential, and challenges to journalism practice (Brennen & Cerna, 2010; Ludlow & Wallace, 2007). The preponderance of disciplinary conversations on virtual reality journalism has been focused on contrasting traditional media and inworld journalistic coverage of issues. Not much attention has been paid to the structural changes that immersive journalism can bring to news practices—or the ways in which it might complement, enrich, or even salvage traditional journalism.

Youth Justice Storytelling

This study is based on a collaborative endeavor in which the students and professors working on the virtual world project interacted with professional journalists at the Juvenile Justice Information Exchange (JJIE.org), a nonprofit news organization located at the Center for Sustainable Journalism at Kennesaw State University. The JJIE.orgspecializes in covering youth justice issues; yet, even in that niche news organization, youth voices are rarely heard.

One barrier in getting youth voices heard is protecting their anonymity. However, that cloak of anonymity can be used to protect unjust systems as much to protect the children themselves. Melissa Sickmund, from National Center for Juvenile Justice, said in 2009: “If the public really knew, they would be appalled, not at the behavior of the kids, but at the behavior of the system” (Cullinan, 2009, para. 22).

Initially, the project planned to use avatars in lieu of the actual names and faces of the youth. Life-like avatars could be effective to protect the youths’ privacy, while also being effective at expressing emotions (Mosera et al., 2007) and conveying those emotions across cultures (Koda & Ruttkay, n.d.). The project’s initial virtual world immersive journalism goal was to have youth tell their individual stories by walking and talking audiences through their experiences of being in detention, of being arrested, of being homeless, and of being lost in the system (Online News Association, 2015).

However, the project leaders changed that strategy, using three different approaches that still guaranteed anonymity for the juveniles. For one machinima’s soundtrack, student actors read actual records from a juvenile’s life and court case, in another a voice-over professional read a juvenile’s poem; and for a third a youth advocate provided the narration for his own childhood story. In future projects the team hopes to have juvenile offenders as avatars telling their real life stories in virtual worlds. All these techniques provide experimental avenues to provide youth the anonymity they deserve, while amplifying their voices.

There are thousands of marginalized youth voices that could be heard. In 2010, 70,000 youth were detained in the U.S. juvenile justice system (Suitts, Dunn, & Sabree, 2014, p. 7). Our project’s online and mobile virtual world experience can inform various groups, including youth themselves and their parents, about the workings of the juvenile justice system. This knowledge could initiate parental involvement. That’s important because, according to Burke, Mulvey, Schubert and Garbin (2014), “[t]he active involvement of parents—whether as recipients, extenders, or managers of services—during their youth’s experience with the juvenile justice system is widely assumed to be crucial” (p. 1).

Virtual prison tours created by incarcerated juveniles where they recount their experience of institutionalization, sentences, challenges, programming, and fears upon release were found to increase awareness among youth who watched the videos and benefited them educationally (Miner-Romanoff, 2014). In the virtual prison tour study at a Midwestern university, 43 undergraduates in a Criminal Justice Program watched videos of juvenile prisoners’ actual accounts and were then surveyed to determine the videos’ effects. According to the student survey responses, the educational benefits of the virtual prison tours included a change in attitude, understanding and perception of the criminal justice system. When asked if the videos helped them to connect theory to practice, 60% of students said it did, and 71% of students said the videos helped them to better understand juvenile corrections. Additional survey data indicated that hearing the juvenile offenders’ personal stories increased student empathy for incarcerated juveniles. Students changed their belief about the efficacy of rehabilitation, counseling, anger management, skills and job training. Of the 43 students surveyed, 71% said the video provided insights into authentic criminal justice experiences and changed their perceptions regarding punishment and rehabilitation. Sixty-three percent of students said the video increased their support for alternatives to incarceration, and 72% said the video increased their support for mental health treatment and education. Furthermore, the videos engaged students. Compared to staged, scripted, sterilized encounters often common in prison tours, the authentic and free flow of the offenders’ actual accounts contributed to students’ deeper understanding of institutionalization.

The project leaders in this project hope their virtual world machinimas, which re-create real-life situations, will also provide positive educational, attitudinal changing experiences. There is a precedent for this. At the Sundance 2016 Film Festival The Guardian premiered 6×9: An Immersive Experience of Solitary Confinement (Sundance, 2015) (Figure 2). This immersive experience is relevant to what we are doing because up to 100,000 prisoners, including juveniles, are held in solitary confinement in the United States at any given time (Eilperin, 2016).

Figure 2. 6×9: An Immersive Experience of Solitary Confinement. A bird’s eye view of solitary cell from the animated VR experience at Sundance Film Festival 2016. Photograph, The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.sundance.org/projects/6×9-an-immersive-experience-of-solitary-confinement (Academic Fair Use).

One of the project’s machinima is being incorporated into an interactive mobile-based app to alert youth to the consequences of juvenile offenses and to deter juveniles from getting involved in crime in the first place. The app design includes a link to Georgia’s state law SB440 that defines when youth will be tried as adults (Campaign for Youth Justice, n.d.). Survey questions to capture audience input about the juvenile’s story appear within the machinima, as do survey results for each question. The virtual world machinima interactive mobile app integrates user interface design principles from studies by Shields (2015) and Simpson (2015). This project demonstrates how one niche area of immersive journalism, sharing juvenile justice stories in virtual world machinima and mobile apps can be accomplished.

The Metaverse of Virtual Reality — And This Project’s Place in that Metaverse

Virtual reality is often equated with 3D headsets like Oculus Rift and 360-degree videos, but as Burdea and Coiffet (2003) remind us, and as we show in greater detail in the next section of this paper, virtual reality transcends hardware, augmented reality or telepresence. It encapsulates the Metaverse’s continuum of virtual experiences, including the 2D Internet. For our purposes here we will be discussing 3D worlds. Within the Metaverse are different types of 3D virtual reality experiences for avatar-embodied users in virtual worlds, and we use the analogy of galaxies and planets to explain them.

The largest galaxy, with thousands of planets, is the Game Galaxy. Game worlds do not allow avatars free will outside the constraints of the game and participants’ avatar identity must be chosen from characters with appearances and roles designed by the game developer. The world itself is fixed and only game developers can make changes or additions to the game world. Many game worlds are single player with the avatar competing against the computer. Others are multi-player where hundreds of players can be online competing simultaneously as individual avatars or in teams of avatars. One of the most popular multi-player game worlds is World of Warcraft (WoW) (http://us.blizzard.com/en-us/games/wow/) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. World of Warcraft. World of Warcraft: Auchindoun Dungeon. Retrieved from WoW presskit http://blizzard.gamespress.com/World-of-Warcraft (Academic Fair Use).

The much smaller Meeting Spaces Galaxy, another part of Virtual Reality Metaverse, is home to many businesses, from small partnerships to large international corporations. These worlds usually reproduce business meeting spaces such as boardrooms or conference centers and offer secure communications. Avatar customization is usually extremely limited, with world customization restricted to adding logos and information displays. Often the world’s virtual services are cloud-based and provide 3D environments suitable for training, collaboration or sales, such as AvayaLive Engage (https://engage.avayalive.com/engage/) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. AvayaLive Engage. Web Collaboration and Virtual Conferencing Tool/

AvayaLive Engage conference room. Avatars attending presentation meeting.

Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pP_ZVLQflpA

The Virtual World Galaxy is the home of social worlds, where the focus is on developing personal and professional relationships. These worlds have visual design themes and include games that are not necessarily required or competitive, allowing participants to acquire objects for the home, clothing and other digital assets. The range of avatars and avatar homes is limited, with customizing restricted to options provided by the game developer. A popular example of a social world is The Sims (https://www.thesims.com/) (Figure 5). The Sims is a life simulation single or multi-player game offering opportunities to develop family, social and business relationships while building your home and community in suburban and urban settings.

Figure 5. The Sims. A popular example of a social world. Retrieved from Electronic Arts Press Room http://info.ea.com/products/p1509/simcity-buildit andhttp://info.ea.com/products/p1504/the-sims-4-get-to-work (Academic Fair Use).

Inside the Virtual World Galaxy are User-Created Virtual Worlds. Each of these worlds are unique, with land masses and content shaped and created by their users. Contained in the world’s software are easy-to-use 3D building tools for creating objects inworld and for importing objects, animations, sounds, textures, and other digital assets into the world. The Second Life Virtual World (www.secondlife.com) is considered to be the first user-created virtual world, with content creation including personal homes, businesses and even universities (Hodge, Collins, & Giordan, 2011) Users have complete creative freedom and many have developed business meeting worlds and game worlds within their user-created worlds. (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Kennesaw State University. Conference center in Second Life virtual campus, 2009. Photo by Gwenette Writer Sinclair.

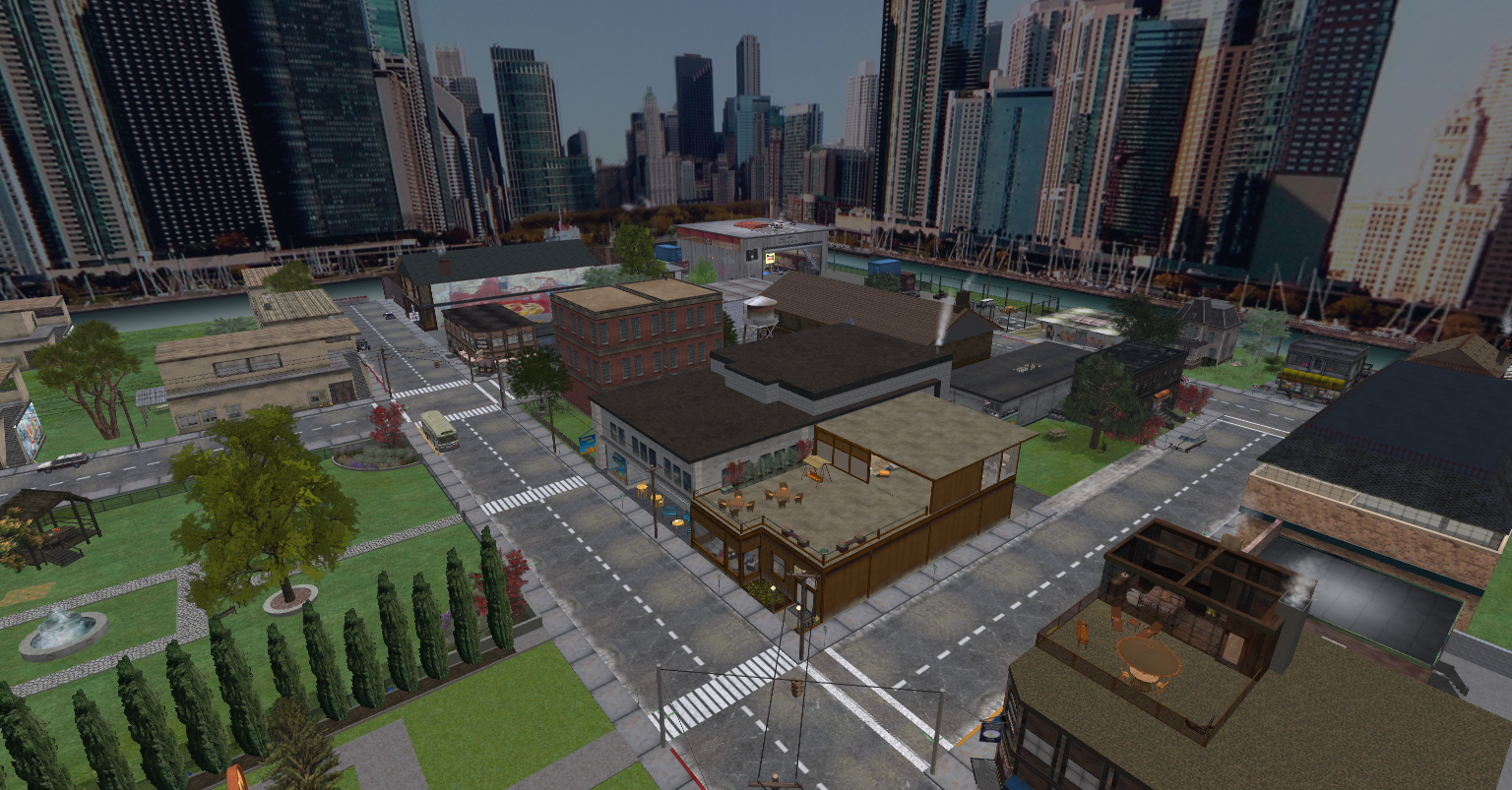

And here is where the reader will find this project’s user-created virtual world. Only a few types of virtual world server software (game engines) support developing user-created worlds. This project employs the open source OpenSimulator server platform (Figure 7). The rationale for our platform choice is discussed in the following section.

Figure 7. The Kid, The Cop, The Punch scenario, built by project interns. OpenSim user-created virtual world scenario for project’s first machinima, Chicago circa 1999 based on photos and Google Earth. Photo by Gwenette Writer Sinclair.

This software’s framework allows the public to connect their computers to project servers and experience our virtual world. Users create avatars on the project’s website and choose from a variety of user world viewer software available to connect to the server and enter the virtual world. Once inworld, they can explore our machinima’s 3D scenarios and interact with the story avatars. Future development could enable users to actually play one of the characters, following the scripted action path or choosing alternative paths at key decision points. User world viewer software programs are available for many platforms, including computers, computers with 3D headsets (i.e. CtrlAltStudio for Oculus http://ctrlaltstudio.com/viewer) and mobile devices.

An Optimum Virtual World Toolkit

Of the many virtual world server platforms available, this project uses the OpenSimulator platform for both inworld digital asset content development and grid management for several reasons. The OpenSimulator platform is open source software and available at no cost for installation on a newsroom’s or university’s own servers. Newsrooms without IT staff can lease server space from OpenSim hosting providers. Hosts manage all the software installation and maintenance at affordable prices starting at $10 per month. Regions and all their content can be saved to a local hard drive as a single OAR (OpenSimulator Archive) file. OAR files can be uploaded to an empty virtual world region, where within minutes a fully developed region appears which can be easily customized for story development and machinima production (Figures 8 and 9).

Figure 8. Empty OpenSim region (16 acres). Within minutes a fully developed region scenario can be uploaded, then customized for story development and machinima production. Photo by Gwenette Writer Sinclair.

Figure 9. OAR file of Chicago scenario (16 acres). OAR upload from hard drive to OpenSim region is simple 3-step process. Photo by Gwenette Writer Sinclair.

These complete OAR files can function as learning tools for groups new to virtual worlds and inworld machinima production. OAR files also greatly simplify shooting segments of ongoing serialized feature stories. One region can easily be used to support numerous scenarios and do fast video retakes by changing out the OAR files as needed.

Digital objects and customized avatars can be created inworld at no cost using simple 3D modeling tools in the OpenSim virtual world viewers. Students and new users benefit from building inworld, concurrently developing inworld avatar skills—movement, camera use, inventory management, communication tools, and documentation techniques. Object development inworld also allows for on-the-fly collaborative design changes and future inworld modifications of assets and re-combination of assets into different scenarios. The inworld weather environment is also easily customized for visual and aural realism. During the actual video capturing of inworld action, the world viewer controls offer complete control of the scenario lighting and camera capture of inworld action from any angle or distance.

Numerous online depositories offer thousands of free Creative Commons licensed digital assets including complete region OAR files, 3D objects, animations, gestures, textures, sounds, scripts for user interactivity, and avatar shapes, skins and wardrobes. These free resources are easily uploaded to the virtual world, allowing inexperienced builders and projects on tight deadlines to quickly assemble a world customized for their project needs at no cost. This greatly reduces the timeframe for asset and machinima production. The development timeline for any size scenario using OpenSimulator inworld build and asset import tools is significantly shorter than when using traditional 3D modeling tools required by other virtual world platforms.

OpenSimulator offers a sensory-rich environment that enhances machinima scenarios and user immersion. While in the 3D virtual scenarios, users can experience streaming music, streaming video and live interactive websites on media screens. Communication tools are robust and include typed and voice for public, group and private chats. The world viewers also offer lighting and sound adjustments allowing individuals to personalize their experience. An important aspect of this customization is the inclusion of a broader user population. Combined with built-in tools like text-to-speech, camera zoom presets and world viewer interface scalability, the population of users with impaired vision, hearing or voice are offered greater access to participate more fully in an OpenSim virtual world. For example, research in this area has shown that interaction between avatars offers non-speaking people new opportunities to converse (Alm et al., 1998).

Two additional intangible, but critically important factors determined the selection of the OpenSimulator platform for this project. One is the support available from professional groups and user forums. OpenSimulator has a strong community of hosting providers, virtual world grid owners, inworld digital asset developers and resident users. Most importantly, the fact that OpenSimulator is the only open source platform that offers allows complete expression of a user’s free will to decide what to develop and which relationships and activities to pursue.

Although other asset development programs and virtual world server platforms/game engines can be used to develop scenarios for machinima production (e.g. Blender, Cry Engine, Delta 3D, Unity), several factors make these options less desirable for a curriculum or internships introducing journalists to the virtual world platform as a storytelling medium. These game engines do not include built-in 3D modeling tools, except for a few with very limited abilities. The financial investment for 3D modeling programs can quickly exceed $10,000. Complex licensing and cost structures for game engines—based on multiple variables including branding, public distribution via different media, commercial use (ie. as part of a newspaper subscribers’ content)—also make it difficult to estimate project costs.

Also, traditional 3D modeling software requires expert level software skills to develop digital assets and assemble scenarios. Game development platforms, which will hold the 3D content, require computer coding skills or the ability to compile scripts from code libraries for scripting avatar-to-avatar and avatar-to-object interactivity.

The most critical negative factor in most game engine platforms is the lack of free will for users inworld. Activities and interactions are limited by what has been coded into the game engine. For this project, using avatars who had no behavior restrictions in an OpenSim developed environment provided a flexible, creative and effective medium for the real journalism stories we wanted to tell.

Methodology

Three of this paper’s authors were active participants in the project, two from its conception in early 2015 and one who joined the project as a student in the fall of 2015. Each had their own separate perspective: One as a professor of journalism, one as a specialist in virtual world development and the third as a student.

Autoethnography is a well cited approach to blend scholarship with personal experience especially as it relates to the scholarship of teaching and learning (Lantz, 2012; Starr, 2010; Taylor & Coia, 2009). We knew our audience would be primarily from journalism-related university programs interested in virtual worlds and virtual reality. So our research answers: “The questions most important to autoethnographers … who reads our work, how are they affected by it, and how does it keep a conversation going?” (Ellis, Section 5, para 5).

Given our three perspectives, collaborative autoethnography was the best fit. Ngunjiri, Hernandez and Chang explain how interaction produces a:

“richer perspective than that emanating from a solo researcher autoethnography. One researcher’s story stirred another researcher’s memory; one’s probing question unsettled another’s assumptions; one’s action demanded another’s reaction. All collaborative autoethnographers as participant-researchers not only made decisions about their research process, but also kept themselves accountable to each other” (2010, Section 4, para 1).

In addition to our own personal experience narratives, students participating in the project were surveyed to ensure the perspective was not ours alone. We also chose a case study approach encouraged by Yin (2003) “when the focus is on a contemporary phenomenon within some real-life context” and when a “how” question is posed in a situation over which the investigators have “little control over events” (p. 1). Our research goal was to explain “how” our project unfolded and changed over the course of a semester in a “real-life” teaching and learning environment.

Results

The Project from the Journalism Professor’s Point of View

The JJIE.org has experimented with alternative forms of journalism in the past, such as comic journalism (Cartoon Movement, 2012) to tell the story of a college student who was almost deported after a routine traffic stop. In early 2015, it was looking for alternative approaches to tell the stories of youth caught in the juvenile justice system. A professor suggested using avatars, which could preserve anonymity for youth whose stories we told. I remembered years earlier, a virtual world developer had created Kennesaw State University’s campus on Second Life (2008) (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Kennesaw State University virtual campus, Second Life 2009. Four region development (64 acres). Photo by Gwenette Writer Sinclair.

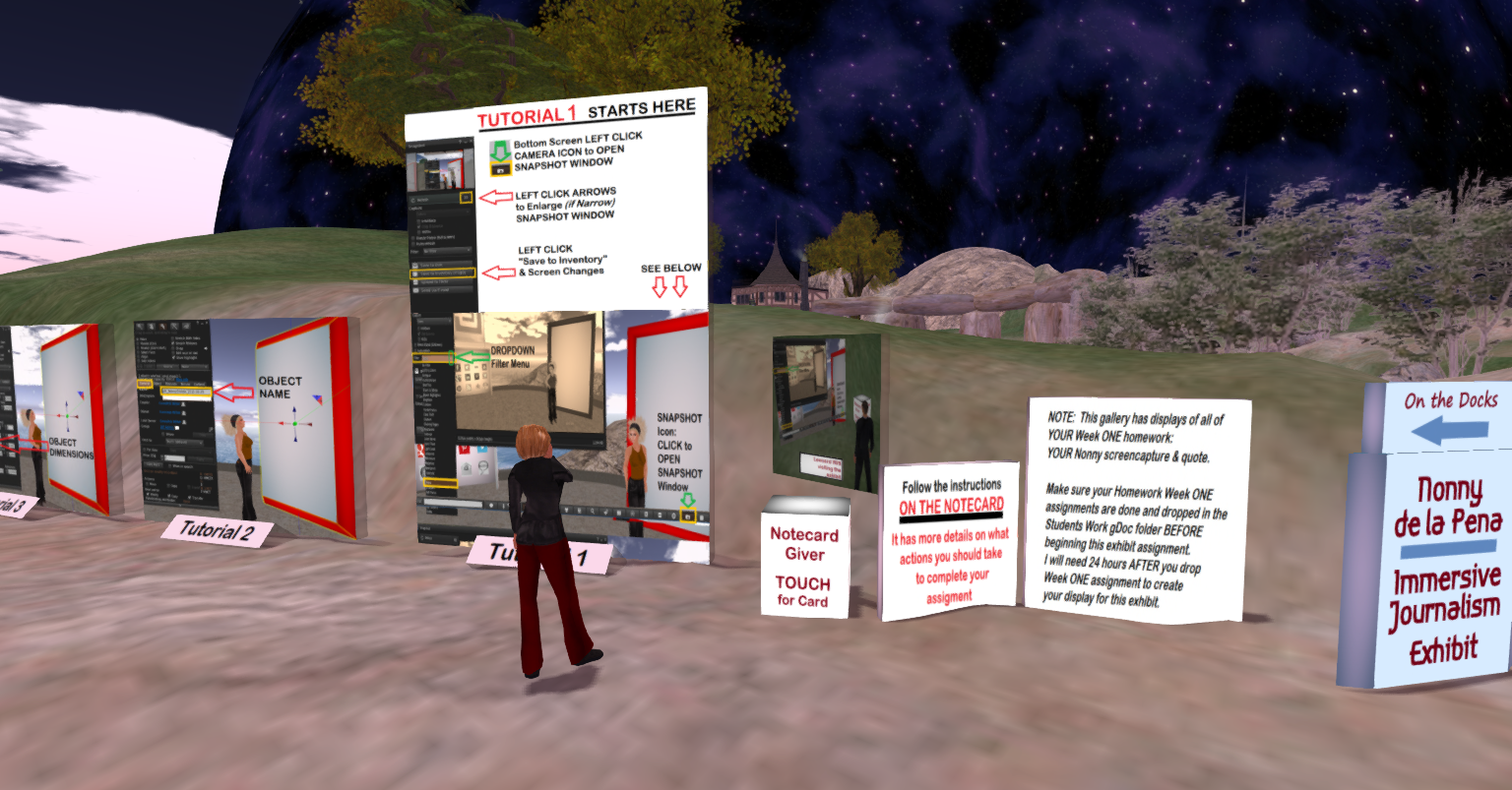

We found her in Orlando, Florida, working with the U.S. Army Simulation Technology Training Center. She was eminently qualified to teach student interns everything about building scenarios and producing machinima in virtual worlds. I knew about journalism, so it was a nice fit. If we count the original grant writing, we have worked together for almost a year, yet we have never met face to face. All her mentoring of our interns has been done via phone conferencing, Skype or inworld (virtual world) meetings. She also took all the interns inworld for fully immersive experiences completing interactive assignments designed to teach both immersive journalism and virtual world avatar skills (Figure 11).

Figure 11. Interns watch inworld skills demonstration. Photo by Leonard Witt.

Our mentoring team included the virtual world developer, an app development professor and me, a journalism professor. Advisors included the JJIE.org’s editor providing investigative journalism advice, JJIE.org’s professional videographer providing video editing advice, and its website developer assisting with our project website (virtualworld.jjie.org) and with audio editing. Immersive journalism in virtual worlds works best as a team endeavor. Since it is still a nascent field, it is unlikely many professors would have all the experience and skill sets needed to teach the journalism, virtual world and machinima aspects of the project.

For instance, just producing our machinima mini-documentaries filmed in our virtual worlds, required many of the same skills needed in making real-world documentaries, including storyboarding, scripting, blocking, camera point of view, lighting and sound.

A look at who is co-authoring immersive journalism leader de la Peña’s research papers provides a glimpse into the depth of thought and disciplines that immersive journalism requires. Her seminal paper (de la Peña, 2010), written with her co-authors, represents skill sets like journalism and interactive media, but also the human sciences. One co-author is based at the Advanced Virtuality Lab which studies “virtuality on the technological, scientific, societal and cultural levels” (http://portal.idc.ac.il/en/main/research/pages/virtuality_lab.aspx) and another from EVENTLab, which researches “how people interact within immersive virtual environments and to identify the underlying brain mechanisms” (http://vulcan.ub.es/eventlab/). Who knew that the words “avatars,” “journalism,” and “brain science” could legitimately be mentioned in one sentence?

On many university campuses, including Kennesaw State, there are many obstacles to interdisciplinary work, so the project team was comprised of grant-funded internships versus developing a scheduled class. Still, it behooves colleges and universities to consider interdisciplinary relationships in setting up a virtual world/virtual reality training program because, as Slater (2014, para 1) points out “… not only does VR ‘really work’ but … it has become a commonplace tool in many areas of science, technology, psychological therapy, medical rehabilitation, marketing, and industry, and is surely about to become commonplace in the home.”

On the project’s team, the following degree majors were represented by the interns: two computer science, one new media arts, two public relations, one media studies, two honors college (one English, one African and African Diaspora Studies) and three journalism.

The project team produced three machinima. The first, The Kid, The Cop, The Punch(used the video soundtrack from a panel discussion I captured months before this project was conceived.

Youth justice advocate Xavier McElrath-Bey told his story of a Chicago police officer chasing and punching him when he was only 12 years old. Project interns used Xavier’s voice from the soundtrack as the sole narration for the machinima. The Chicago-based inworld scenes, the avatar characters and the actions are all acted out as Xavier’s taped voice tells the story. The Kid, The Cop, The Punch would fall in the media category ofThe New York Times’ video Op-Docs (2016), which is a “forum for short, opinionated documentaries, produced with wide creative latitude and a range of artistic styles, covering current affairs, contemporary life and historical subjects.”

The third machinima, Forgive, also fits into the Op-Docs category. The Beat Within, which publishes writing and art from incarcerated youth, provided a moving autobiographical poem written by a teenage ward of the court in Los Angeles’ Central Juvenile Hall. She wanted to remain completely anonymous, so a member of Kennesaw University’s spoken word club read the poem. Forgive is currently under production as an impressionistic inworld machinima.

To produce the second machinima, Christopher: A Child Abandoned, Deprived & Imprisoned the project took an unexpected turn.

Originally, the project interns sought youth in the system to tell their verifiable personal experiences. Using avatars would allow their voices to be heard and they would be active participants in the storytelling process. The virtual world would provide the cover needed to protect their anonymity, privacy and safety. At the same time, viewers could experience empathy (Milk, 2015) in ways virtual worlds make possible. However, when team members approached a lawyer for story leads, he instead handed them thousands of pages of documents chronicling every aspect of Christopher Thomas’s life starting at age two. Now age 28, Thomas has been in prison for the past 15 years, serving 40 years for the crime of being an unarmed tag-along in a non-lethal shooting at age 14. This project would possibly be Christopher’s last chance for the public to hear the story of his experience in the justice systems.

The journalists knew how to write the textual part of this story. The first fact-filled draft was over 8,000 words. Condensing that into a virtual world mini-documentary in one semester was not easy. This was real journalism, so everything in the machinima had to be based on verified facts. Project interns read thousands of document pages to find pivotal life experiences and critical fact excerpts from records written by Thomas’ family, social workers, teachers, mental health professionals and police who worked the case. These were augmented by transcriptions from sentencing hearings. These real words were read and recorded by project interns and staff, just like real actors recreating scenes in a real-world documentary. The voices were edited together with machinima footage of virtual world avatar action. The avatars were modeled after the real-life people in Thomas’ story, using photos as source material (Figure 12).

Figure 12. Real people to avatars. Photo by Claire Bohrer.

This project’s virtual world scenarios and avatars may appear less visually sophisticated and more two-dimensional than the deep immersive journalism produced for viewing in headsets like the Oculus Rift. However, in his review of the literature, Foreman (2009) found that “in many studies reviewed … head immersion VR has been said to create a greater feeling of presence than desk-top presentation, although VEs [virtual environments] can be effective when programmed using relatively cheap software … and presented on a cheap monitor” (p. 20). So, if building big studios with expensive headset-related technology is not possible, starting with inexpensive, relatively easy-to-use tools like OpenSimulator can be an excellent launching pad for more technologically sophisticated projects in the future. Every journey begins with a first step.

Our first step provided excellent intern training in the same principles and skill sets used with more expensive software and gear. The investment is very affordable for even the smallest colleges. Plus, OpenSimulator virtual worlds and machinima are accessible to the broad audience of computer and mobile device users. It is part of a low-cost progression toward de la Peña’s deep immersive journalism described earlier. This first step also fulfilled the proposal project goal to “demonstrate how students working in a real newsroom can use existing virtual world (VW) tools to begin that journey to VR storytelling” (Online News Association). Indeed, OpenSim world viewers (software used to enter the world) allow users the option to experience the 3D world with an Oculus headset. Additionally, even without the headset, the world viewer software has camera settings that can capture 360-degree machinima for watching with Google Cardboard or similar devices. This offers experiences similar to De la Peña’s Kiya, premiered at the Sundance Film Festival (2016). It is an emotionally disturbing, deep immersive journalism story of domestic violence, which was also showcased on The New York Times’ virtual reality pages. This is a bonafide journalism medium.

The Project from the Virtual World Developer’s Point of View:

The invitation to work with a journalism professor and interns to create a virtual world for immersive journalism was an appealing creative challenge. Once the grant was awarded, I began gathering Creative Commons licensed 3D assets and established an OpenSimulator virtual world location on an OpenSim hosting service. That was the easy part.

The main challenge was our small window of time from project conception to completion. Two summer interns would produce a short proof-of-concept machinima and assist in preparing the virtual world for the fall interns, but the work of finding and writing stories, building 3D scenarios, scripting and producing machinimas and developing a mobile app would happen during the short 16-week fall semester. Another challenge involved optimizing team member talents and teaching new skills to everyone, while satisfying the project grant requirements and the learning expectations of 12 interns.

The summer interns—two computer science majors—arrived enthusiastic about learning OpenSimulator software. They were skilled and comfortable working with me remotely. I was impressed when they installed the OpenSimulator server software on their own gear, which was not an internship requirement. It was the beginning of students creating their own team talent niche. The summer interns became Weproducers for two machinima, managing the scenario development, filming and sound recordings. My original production pipeline chart had teams assigned to each machinima to facilitate more students learning about virtual world development and machinima production. It contained lists of activities with learning outcomes for each team role. After the fall interns arrived, it was clear they each had expertise to contribute and specific new skills they wanted to learn. We then archived the original production pipeline chart.

The fall semester started and we began a fast-paced race to our deadline. Every week included inworld tutorial assignments for the interns. Then we found the Christopher Thomas story. Suddenly, no one had time for inworld activities. Interns now focused on using Google Docs not only as planned—for virtual world and machinima production task management—but to track the Thomas story research data. I archived the remainder of my inworld assignments.

As I watched the project’s evolution and the interns at work, it was clear a very creative, collaborative process was occurring. In just 16 weeks, the team produced two virtual world documentary machinimas filmed and edited by three people with no previous experience. We enlisted voice-over talent from our intern team, produced an alpha version of a mobile app created by our two uber producers, and completed the second draft of an investigative long-form journalism story collaboratively researched and written by over a dozen people.

We also developed two OpenSimulator virtual world regions for machinima production and one region designed to lead teams new to virtual worlds and machinima through interactive tutorials (Figures 13 and 14). It did not all happen according to my plans, but what did happen met our project goals and surpassed my expectations of the interns’ collaboration capabilities.

Figure 13. Homework meeting inworld. Photo by Gwenette Writer Sinclair

Figure 14. Homework tutorial inworld. Photo by Gwenette Writer Sinclair

Three students internships have been extended to complete our third machinima and mobile app. We are also producing a complete hands-on toolkit with an instructional manual including all the best practices garnered from our experience. It will include copies of the project’s virtual world regions with interactive training pathways, immersive journalism learning activities, an avatar character production workshop, and machinima scenarios. The toolkit will be available as a free download on the project’s website.

From my perspective, the project was a successful, transdisciplinary collaboration. It demonstrated that virtual world immersive journalism skills can effectively be taught to university students in a 3D virtual world. Our diverse team learned remote collaboration skills and new software—including the OpenSimulator virtual world platform, the Firestorm world viewer, video capturing and editing tools and Google Docs—to produce immersive journalism stories about the juvenile justice system. As a team we were flexible, creative and determined to finish the race.

The Project from a Participating Student’s Point of View:

As an English major, I was interested in journalism, but before this project, was neither familiar with immersive journalism nor virtual worlds. I was excited to be a part of something so innovative and new to me.

In August, I met with our interdisciplinary group of 12 undergraduate students at The Center for Sustainable Journalism, where we would meet weekly for the next 15 weeks. Each of us was also required to work an additional 12 hours a week on the project. By the second week, I was completely committed to my internship, with responsibilities including project manager, researcher, process blogger and journalist.

To understand immersive journalism, we were first introduced to our virtual world, learning how to communicate with each other inworld and navigate through it with our avatars. I was fascinated by the notion of taking on a separate persona, being able to walk, run, and even fly through a different world. I learned anyone could build a world in this OpenSimulator environment, or simply explore the hundreds of OpenSim worlds and the community of thousands of OpenSim world users and creators.

Initially, I researched virtual worlds as an emerging journalism platform and completed inworld assignments. When we came upon the Christopher Thomas story, we all switched to journalist mode. The story came to life as I researched facts through handwritten and court documents, live interviews with people associated with the crime and trips to the story’s locations. After the journalism team relayed all the information to our three-person machinima team, the story came to life in a completely different way.

With traditional journalism, an audience would only be able to read about Thomas’ story. With the machinima, the audience would be taken back in time to the 1990s, to experience his life from age two until he was incarcerated at age 14.

Student Project Intern Surveys

After the project, student interns were surveyed to gather their perspectives of the project. Ten interns, including myself, completed the survey.

Student interns heard about the project via e-mails, Facebook, and Kennesaw University career website postings. Coming into the project with “an open mind,” students were excited to be a part of an innovative, exciting project. With little virtual world experience before the project, many interns felt challenged by the inworld assignments, as they struggled with creating prims and learning the controls. Yet, students were fascinated with aspects of the virtual world like flying and teleporting to different virtual worlds and how real the virtual world could feel.

By the end of the project, all the interns agreed that they had expanded their knowledge of virtual worlds and how to navigate their avatars through them. Furthermore, although none of the interns had ever heard of a machinima before the project, they all agreed they had a better understanding of what a machinima is and how one is produced after the project. Also, all interns stated that they were not very familiar with the term immersive journalism at the beginning of the project, but by the end, they were able to define it in their own words.

When asked at the end of the project if virtual worlds were an effective way to tell news stories, the consensus was yes. Interns noted the effectiveness of virtual world journalism, saying it allows audience members to visit past events and get a first-hand, visual feel of the story as it unfolds. Overall, the majority of the interns agreed that the virtual world platform could have a future in journalism.

However, despite the overall positive assessment of virtual world journalism, there were concerns about using virtual worlds to tell news stories. One concern was the amount of time allotted to write and produce the stories, while another was the question of whether or not virtual worlds can be as vivid and descriptive as the written word.

Student Audience Perceptions of Virtual World Journalism

To test immersive journalism’s ability to generate empathy in college students, the JJIE Virtual World Team presented its project’s machinimas along with examples of de la Peña’s work to students at Kennesaw State University.

After discussing immersive journalism, 24 student attendees, most from a Mass Media Studies Communications Class, were surveyed on their perceptions of virtual world journalism vs. traditional journalism. Eighteen of the 24 students were “not familiar” or had “never heard of” immersive journalism, the rest being “somewhat familiar.” Twenty-three students had little to no experience with virtual worlds and only five students had viewed a machinima before.

When asked after the presentation if traditional textual journalism or virtual world journalism would appeal more to an audience, 43% said virtual world journalism.

When asked why virtual world journalism is effective for presenting stories, students explained how it triggers emotions and enables participation, and that it is more realistic and gives the audience the ability to connect with the story.

While many agreed that virtual world journalism would appeal more to an audience, 14% had reservations. These students said that textual journalism is simpler, since everyone can read and not everyone wants to have to explore for information. Others said that textual is more cost-effective and is able to reach a wider audience.

However, 43% of students were still torn between the two, noting variables like accessibility, audience age and interests. These students agreed that both are effective in certain scenarios and for certain audiences with different demographics.

Conclusions

The Virtual Reality (VR) Metaverse is enormous and filled with enormous possibilities. Initiating this type of project requires determining what game engine, what server equipment and what type of world content is optimal for a project. This demands careful evaluation of multiple variables. Having an experienced virtual world (VW) developer on board to make these decisions is crucial. For this project, the VW expert set up both the virtual world regions and created the 3D curriculum training content to teach the interns inworld avatar skills and the principles of immersive journalism machinima production. The participation of a VW expert meant the rest of the project team only had to learn the virtual world and production basics, enabling them to focus on contributing their own unique experience and knowledge to the collaborative project. As stated previously, VR is already being used in a variety of fields from medicine to marketing to journalism (Slater 2014, para 1). So, VR projects provide the opportunity to be interdisciplinary and early planning should be as transdisciplinary as possible.

This project opens the door for future study on the impacts of virtual worlds and mobile virtual world machinima on: (1) public awareness, (2) juvenile offenders education, and (3) deterring juveniles from getting trapped in the system.

An article by Lenhart (2015) of Pew Research Center shows how pervasive digital technologies are in the daily lives of young people. These technologies, especially mobile applications, could be pivotal in reaching youth before they get caught in the juvenile justice system and reaching youth already in the system.

Interactive mobile apps can be combined with this project’s machinima, allowing youth users to consider different options available to the characters at pivotal action points. Choices the youth make can lead to new storylines and more choices, as well as to websites or media with related information. And each choice can lead to polls showing how their decisions compare with their peers. Research by Shields (2015) has shown this to be an effective method for engaging youth in mobile apps.

These interactive apps and the actual 3D virtual world of the machinima scenarios can be integrated into a curriculum for schools, out-of-school programs and juvenile detention facilities. Mantovani (2003) noted that for effective transfer of knowledge in virtual environments, “the experience should seem real and engaging to participants, as ‘if they were in there’: they should feel (emotionally and cognitively) present in the situation.” Youth could enter the 3D virtual world (alone or with friends) to interact directly with AI story characters (artificial intelligence robot avatars), or take on the role of a story character, making their own action choices. They could also record their experiences using a simple inworld snapshot tool and share in real time on social media. These inworld experiences would provide a strong sense of personal identity and presence in the 3D story scenario, as well as social presence while engaging with other avatars. Interactive inworld objects would instantly show youth how their action choices compare with those of their peers. Research data could be gathered from pre- and post-experience surveys, polls within the inworld and app experiences themselves and video capture of the youth using the 3D virtual world. This data would provide feedback for future immersive experience development, and information to youth providers and juvenile justice system decision makers.

One goal of this paper is to demonstrate how the immersive journalism work of researcher and practitioner Nonny de la Peña could be emulated in a university setting. This project’s research chronicles the collaborative hands-on experiences that culminate in successful proof-of-concept student productions. Since this project used the free OpenSimulator virtual world platform and the machinima scenarios were developed using only a few custom objects and many free Creative Commons assets, it was a very fast and very inexpensive project. A $35,000 Online News Association grant enabled the team mentors to successfully introduce students to the practice of truth-based storytelling using virtual world scenarios and avatars to produce immersive journalism stories.

Our research also addresses topics that are being confronted by journalism-industry-based research (Aronson-Rath et al., 2015), including but not limited to the notions that journalists must decide where their projects fit on the VR technology spectrum, use production equipment that best fits their workflow and develop teams that can work well together collaboratively (para 1-8). With the industry increasingly embracing immersive journalism (Brustein, 2014; Manly, 2015; Munster et al., 2015), it is recommended that journalism schools equip their students with the skills to do virtual reality journalism.

To be sure, many universities had incorporated virtual worlds into their journalism curricula. Several universities established virtual classrooms in the user-created virtual world of Second Life from 2004 to 2010, but $150 to $350 monthly per region fees made it challenging for most university budgets to sustain their projects, although some remain. The user-created virtual worlds on the OpenSimulator platform are currently a popular low cost alternative for many university departments. An accurate count of university programs on either platform is difficult since statistics are available only through self-reporting lists. Information about several journalism programs can be found through research. For instance, from 2009 to 2011, the London School of Journalism offered journalism classes in Second Life (Ward, 2009). The Knight Center for Journalism and a researcher from San Diego State University also collaborated in 2010 to offer journalism courses in Second Life focused on teaching math techniques for reporting in a simulated crisis scenario (Knight Center News, 2010). However, offering journalism classes in a virtual reality platform is not the same thing as teaching the nuts and bolts of virtual reality journalism or, better yet, immersive journalism.

Our support for teaching immersive journalism to university students is inspired not just by the success of our work, but by the examples such as DePaul University’s journalism school, which offered news writing classes that explored immersive journalism and experimented with virtual reality storytelling (DePaul University, 2015). A virtual reality hackathon, “Hack the Gender Gap,” hosted by the USC Annenberg School of Communication and Journalism and MediaShift in October 2015 also challenged teams to develop immersive journalism campaigns for real-life companies (Center for Media & Social Impact, 2016).

Although immersive journalism does not yet replace traditional journalism, especially in the breaking news category, it can complement, and at times replace, long-form journalism, especially for media-averse youth audiences who prize expressive spontaneity. With the ubiquitous use of more powerful consumer technology devices, mobile accessibility and ever-increasing bandwidth, the average citizen is consuming news on multiple devices and media platforms. This project has shown the viability of teaching university journalism students the fundamental techniques for producing immersive journalism stories and preparing them to be journalists in the rapidly changing field of technologically enhanced, immersive journalism.

Acknowledgement: Funding for this project was administered by the Online News Association (ONA) Challenge Fund for Innovation in Journalism Education with support from Excellence and Ethics in Journalism Foundation, the Robert R. McCormick Foundation, Knight Foundation, the Democracy Fund, and the Rita Allen Foundation.

References

About Op-Docs. (2015, January 22). The New York Times. Retrieved January 2, 2016, fromhttp://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/22/opinion/about-op-docs.html?_r=0

Alm, N., Arnott, J. L., Murray, I. R., & Buchanan, I. (1998). Virtual reality for putting people with disabilities in control. Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, 2, 1174-1179.

Aronson-Rath, R., Milward, J., Owen, T., & Pitt, F. (2015, November 11). Virtual reality journalism. Tow Center for Digital Journalism. Columbia Journalism School. Retrieved from http://towcenter.org/research/virtual-reality-journalism/

The Beat Within. (1996). About us. Retrieved fromhttp://www.thebeatwithin.org/about-us/

Biocca, F., & Delaney, B. (1995). Immersive virtual reality technology. In F. Biocca and M. R. Levy (Eds.), Communication in the age of virtual reality (pp. 57-126). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Brennen, B., & Cerna, E. (2010). Journalism in Second Life. Journalism Studies, 11 (4), 546-554.

Brustein, J. (2014, September 22). A newspaper’s first trip into virtual reality goes to a desolate farm. Bloomberg. Retrieved fromhttp://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2014-09-22/gannetts-first-virtual-http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2014-09-22/gannetts-first-virtual-reality-journalism-features-a-desolate-farm.

Burdea, G. C., & Coiffet, P. (2003). Virtual reality technology (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Burke, J. D., Mulvey, E. P., Schubert, C. A., & Garbin, S. R. (2014, April 1). The challenge and opportunity of parental involvement in juvenile justice services. Child and Youth Services Review, 39, 39-47. doi:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3989100/

Campaign for youth justice (n.d.). Fact sheet: SB440. Retrieved from

http://www.campaignforyouthjustice.org/Downloads/KeyResearch/MoreKeyResearch/GAFactSheetonSB440.pdf

Cartoon Movement. (2012). Partnership: Juvenile justice information exchange.

Retrieved from http://www.cartoonmovement.com/project/9

Center for Media & Social Impact (2015). USC Annenberg hosts virtual reality and immersive journalism hackathon. Retrieved fromhttp://www.cmsimpact.org/blog/usc-annenberg-hosts-virtual-reality-and-immersive-journalism-hackathon

Cruz, R., & Fernandes, R. (2011). Journalism in virtual worlds. Journal of Virtual WorldsResearch, 4(1), 3-13.

Cullinan, K. (2009). Juvenile justice and openness. The News Media & The Law, 4. Retrieved from http://www.rcfp.org/browse-media-law-resources/news-media-law/news-media-and-law-summer-2009/juvenile-justice-and-openne

De la Peña, N. (2016). Kiya, where virtual reality takes us. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/21/opinion/sundance-new-frontiers-virtual-reality.html?r=0

De la Peña, N. (2015, May). The future of news? Virtual reality [Video file]. Retrieved fromhttps://www.ted.com/talks/nonny_de_la_pena_the_future_of_news_virtual_reality?language=en

De la Peña, N., Weil, P., Llobera, J., Spanlang, B., Friedman, D., Sanchez-Vives, M.V., & Slater, M. (2010). Immersive journalism: Immersive virtual reality for the first-person experience of news. Presence: Teleoperators & Virtual Environments, 19(4), 291-301.

DePaul University (2015, November). Journalism students explore virtual reality viewing, immersive journalism. Retrieved fromhttp://communication.depaul.edu/about/news-and-events/2015/Pages/journalism-vr.aspx

Eilperin, J. (2016, January 26). Obama bans solitary confinement for juveniles in federal prisons. Washington Post. Retrieved fromhttps://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/obama-bans-solitary-confinement-for-juveniles-in-federal-prisons/2016/01/25/056e14b2-c3a2-11e5-9693-933a4d31bcc8_story.html

Electronic Arts. (2016). Electronic Arts Press Room [digital images]. Retrieved fromhttp://info.ea.com/products/p1509/simcity-buildit (2016) andhttp://info.ea.com/products/p1504/the-sims-4-get-to-work (2015)

Ellis, C., Adams, T. E., & Bochner, A. P. (2011, January). Autoethnography: An overview.Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 12(1). Retrieved from http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1589/3095

Foreman, N. (2009). Virtual reality in psychology. Themes in Science and TechnologyEducation, 2(1-2), 225-252. Retrieved fromhttp://earthlab.uoi.gr/theste/index.php/theste/article/view/33

Hodge, E., Collins, S., & Giordano, T. (2011). The virtual worlds handbook: How to useSecond Life and other 3D virtual environments. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers.

Immersive Journalism. (2012). Hunger in LA: An immersive journalism premiere. Retrieved from http://www.immersivejournalism.com/hunger-in-los-angeles-machinima-video/

Knight Center News. (2010). Knight Center tests the use of Second Life in journalism training. Retrieved from https://knightcenter.utexas.edu/knight-center-tests-use-second-life-journalism-training

Koda, T., & Ruttkay, Z. (2009). Cultural differences in using facial parts as cues to

recognize emotions in avatars. In Intelligent Virtual Agents, Volume 5773 of series

Lecture Notes in Computer Science (517-518). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Latar, L. N., & Nordfors, D. (2009). Digital identities and journalism content: How artificial intelligence and journalism may co-develop and why society should care.Journalism Innovation, 6(7), 1-44.

Latz, A. (2012). Flow in the community college classroom? An autoethnographic exploration. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 6(2),1-13. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/ij-sotl/vol6/iss2/15

Lenhart, A. (2015, April 09). Teens, social media & technology overview 2015. [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/04/09/teens-social-media-technology-2015/

Ludlow, P., & Wallace, M. (2007). The Second Life Herald: The virtual tabloid that witnessed the dawn of the metaverse. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Lugrin, J., Latt, J., & Latoschik, M. E. (2015). Avatar anthropomorphism and illusion of body ownership in VR. Proceedings of the IEEE VR 2015.

Manly, L. (2015, November 19). A virtual reality revolution, coming to a headset near you. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/22/arts/a-virtual-reality-revolution-coming-to-a-headset-near-you.html

Mantovani, F., & Castelnuovo, G. (2003). Sense of presence in virtual training: Enhancing skills acquisition and transfer of knowledge through learning experience in virtual environments. In G. Riva, F. Davide, & W.A IJsselsteijn (Eds.), Being there: Concepts, effects and measurement of user presence in synthetic environments (167-181). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: IOS Press.

Milk, C. (2015, March). How virtual reality can create the ultimate empathy machine [Video file]. Retrieved fromhttps://www.ted.com/talks/chris_milk_how_virtual_reality_can_create_the_ultimate_empathy_machine

Miner-Romanoff, K. (2014). Student perceptions of juvenile offender accounts in criminal justice education. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 39(3), 611-629. doi:10.1007/s12103-013-9223-5

Moser, E., Dernt, B., Robinson, S., Fink, B., Gurb, R.C., & Grammere, K. (2007). Amygdala activation at 3T in response to human and avatar facial expressions of emotions. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 161(1), 126-133.

Munster, G., Jakel, T., Clinton, D., & Murphy, E. (2015, May). Next mega tech theme is

virtual reality. Piper Jaffray Investment Research. Retrieved from

https://piper2.bluematrix.com/sellside/EmailDocViewer?encrypt=052665f6-3484-40b7-b972-bf9f38a57149&mime=pdf&co=Piper&id=reseqonly@pjc.com&source=mail

Ngunjiri, F. W., Hernandez, K. C., & Chang, H. (2010). Living autoethnography: Connecting life and research [Editorial]. Journal of Research Practice, 6(1), Article E1. Retrieved from http://jrp.icaap.org/index.php/%20jrp/article/view/241/186

Online News Association (2015, April 24). Winner: Kennesaw State University. Retrieved from http://journalists.org/programs/challenge-fund/2015-16-challenge-fund-winners/winner-kennesaw-state-university/

Second Life. (2008, September 21). Metanomics [Video file]. Retrieved from

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2BzQwVy1yCc

Shields, L. (2015, December 22). How design can help teens prevent dating violence

and revive a nonprofit brand. Retrieved from

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/how-can-great-strategy-design-revive-non-profit-brand-lance-shields

Short, J., Williams, E., & Christie, B. (1976). The social psychology of telecommunications. London: John Wiley & Sons.

Simpson, J. (2015, November 30). 15 reasons your brand should be on Snapchat

[Weblog]. Retrieved from https://econsultancy.com/blog/67257-15-reasons-your-brand-should-be-on-snapchat/

Sinclair, G. W. (Photographer). (2008). Explore Kennesaw State University in Second Life!![digital images]. Retrieved fromhttps://www.flickr.com/photos/gwenette/sets/72157622460858005/

Slater, M. (2014, May 27). Grand challenges in virtual environments. Front. Robot. AI

1:3. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/frobt.2014.00003

Starr, L. J. (2010, July). The use of autoethnography in educational research: Locating who we are in what we do. Canadian Journal for New Scholars in Education, 3(1) Retrieved from http://cjnse-rcjce.ca/ojs2/index.php/cjnse/article/view/149

Suitts, S., Dunn, K., & Sabree, N. (2014). Just learning: The imperative to transform juvenile justice systems into effective educational systems. Retrieved fromhttp://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED555854

Sundance. (2015, December 3). Sundance institute celebrates new frontier 10th anniversary at 2016 festival. Retrieved fromhttps://www.sundance.org/blogs/news/new-frontier-projects-and-films-announced-for-2016-festival

Taylor, M. & Coia, L. (2009). Co/autoethnography: Investigating teachers in relation. In C. Lassonde, S. Gallman & C. Kosnik (Eds.), Self-Study research methodologies for teacher educators (pp.169-186). Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

Totilo, S. (2007). Burning the virtual shoe leather: Does journalism in a computer world matter? Columbia Journalism Review, 46(2), 38-44.

Ward, A. (2009, February). London School of Journalism goes virtual. Publishing Talk. Retrieved from http://www.publishingtalk.eu/journalism/london-school-of-journalism-goes-virtual/.

Weinberger, M. (2015, March 29). The company was 13 years early to virtual reality—and it’s getting ready to try again. Business Insider. Retrieved fromhttp://www.businessinsider.com/second-life-is-still-around-and-getting-ready-to-conquer-virtual-reality-2015-3

Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Leonard Witt is executive director of the Center for Sustainable Journalism (CSJ) at Kennesaw State University. In 2008, he was named an Eminent Scholar by the Board of Regents of the University System of Georgia and awarded the Distinguished Service Award for Kennesaw State University. With $1.5 million in funding from the Harnisch Foundation, he founded the CSJ in 2010. The CSJ’s mission is to discover innovative ways to produce financially sustainable, high quality and ethically sound journalism. It produces applied research, builds collaborations and advances innovative projects to test the viability of niche, nonprofit journalism. In keeping with that mandate, the CSJ now publishes the Juvenile Justice Information Exchange (JJIE.org) and Youth Today. With a combined 1.25 million page views annually, they cover youth justice and youth development issues daily with professional journalists. The CSJ works closely with university faculty and employs about 20 annually students in journalism, social media and advertising and circulation sales. Witt was a journalist for more than 25 years, including being editor of Sunday Magazine at the Minneapolis Star Tribune and Minnesota Monthly magazine. Before entering academia in 2002, he was the executive director of the Minnesota Public Radio Civic Journalism Initiative.

Farooq Kperogi, Ph.D., is an assistant professor of Journalism and Emerging Media in the School of Communication and Media at Kennesaw State University, Georgia. His scholarly work on a wide range of communication topics such as online journalism, alternative and citizen journalism, diasporic media, journalistic objectivity, public sphere theory, indigenous language newspaper publishing in Africa, cybercrime, international English usage, online sociability of digital migratory elites, social media journalism, and media theory has appeared in The Review of Communication, New Media & Society, Journal of Global Mass Communication, Journal of Communications Media Studies, Asia Pacific Media Educator and in several book chapters. He is also the author of Glocal English: The Changing Face and Forms of Nigerian English in a Global World (2015), and blogs atwww.farooqkperogi.com.

Gwenette Writer Sinclair, CEO of 1 Virtual World Development, is a Metaverse strategist, virtual world developer, mixed reality event producer and website designer. She specializes in virtual university campus design, immersive 3D training facilities, virtual curriculum implementation, custom avatar design, international virtual conference management and project-focused WordPress site development. As a virtual world content creator her focus is on Transitional Replica environments that provide the realism of a physical world locations and seamlessly incorporate the unique affordances of the 3D virtual platform. An experienced K-12 teacher and administrator in many innovative educational systems, she also provides customized one-on-one or group training in virtual world skills to her clients. Sinclair’s Metaverse projects include collaborations with Rutgers University, Kennesaw State University, University of Texas, University Central Florida, King’s Hospital School (Dublin, Ireland), Junior High School of Rhodes (Greece), Peace Train Charitable Trust, Children’s Hospital of Chicago, US Army MOSES Project, Second Life Community Conference, OpenSim Community Conference, and Broadway Producer Tom Polum. See Kennesaw State University campus project herehttps://www.flickr.com/photos/gwenette/albums/72157622460858005. For more information https://www.linkedin.com/in/gwenettewritersinclair

Claire Bohrer is a senior at Kennesaw State University (KSU). She plans to graduate in May 2016 with a Bachelor of Arts degree in English and a minor in Spanish. She is an Honors Student and she is also an avid athlete, being on the KSU track and cross country team since her freshman year. Since fall 2014, She has been a writing assistant at the KSU Writing Center, assisting students of all majors with various papers. She has always enjoyed writing, which is what led her to apply for the JJIE Virtual World Journalism internship. She saw this project as the perfect opportunity to learn more about journalism and the emerging field of virtual world immersive journalism. Although the project has ended, Claire still works at the Center for Sustainable Journalism, where she is a part-time editorial assistant for two publications, the Juvenile Justice Information Exchange (JJIE.org) and Youth Today. After graduation, Claire plans to continue her research and work in the journalism or communications field.

Dr. Solomon Negash is professor of Information Systems and Executive Director of the Mobile Application Development Center in the Coles College of Business at Kennesaw State University. He earned his Ph.D. from Claremont Graduate University, Claremont, California. His research focuses on mobile applications, classroom technology, technology adoption, technology transfer, and outsourcing. He has published over a dozen journal papers, two edited books, several book chapters, and over three dozen conference proceedings. Professor Negash’s experience includes 20 years in industry and 15 years in academe. His industry service includes plant manager, consultant, strategic thinking and planning, coordinator of an international Ph.D. program, editor-in-chief, founder and first chairman of the Ethiopian Information and Communication Technology advisory body, and founder and chairman of a charitable organization. The awards Professor Negash received include distinguished intellectual contribution award, distinguished e-Learning award, distinguished graduate teacher award, distinguished service award, and international goodwill and understanding award.