More than code: The complex network that involves journalism production in five Brazilian robot initiatives

By Silvia DalBen and Amanda Jurno

[Citation: DalBen, S. and Jurno, A. (2021). More than code: The complex network that involves journalism production in five Brazilian robot initiatives. #ISOJ Journal, 11(1), 111-137.]

Algorithms are part of several routine steps in online journalism and are important actors in automated journalism. In this research, the researchers argue that the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in newsrooms involves much more than just the ‘robot reporter’, coding and programmers. Instead of humanoid figures, one can say the focus is about computers, software, algorithms, databases, and many humans. Seeking the professionals involved in those initiatives in an attempt to demonstrate the complexity of networks associated with automated journalism, this study describes and analyzes five robots created in Brazil: [1] Da Mata Reporter; [2] Rosie from the Serenata do Amor operation; [3] Colaborabot; [4] Rui Barbot from Jota; and [5] Fatima from Aos Fatos checking agency. In common, those initiatives use AI to process large volumes of data and use Twitter’s platform as the main channel to distribute information and interact with readers.

The most common initiatives in automated journalism use algorithms to produce data-driven stories about sports, finance, elections, crimes, earthquakes, among others, written with repetitive narrative structures (Carlson, 2014; Dörr, 2015; Graefe, 2016; Van Dalen, 2012). The first applications of Natural Language Generation (NLG) software in journalism were weather forecasts (Glahn, 1970; Reiter & Dale, 2000) in the 1970s, but the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in newsrooms became popular after being adopted in the past decade by great enterprises with international repercussions such as Forbes, Los Angeles Times, Associated Press, Le Monde, The Washington Post, Southern Metropolis Daily (China), Deutsche Welle and MittMedia (Sweden) (D’Andréa & DalBen, 2017).

Also named as “robot reporters,” the automated production of news stories by those newsrooms carries a negative symbolism and is considered by some journalists a threat that could replace them in the future. Sometimes associated with humanoid figures, inspired by science fiction novels and films, automated stories are not written by robots and are actually produced by computers, software, algorithms and databases, elements that are part of journalism practice for at least four decades (Linden, 2017).

In recent years, scholars have focused on how readers perceive automated news (Clerwall, 2014; Graefe et al., 2016; Haim & Graefe, 2017) and their work revealed a difficulty in differentiating automated content from texts written by human reporters. Automated journalism is considered more descriptive, boring, informative and objective compared to stories written by journalists that are more interesting, coherent and pleasant to read (Clerwall, 2014).

Automated journalism is defined by some scholars as narratives produced by software and algorithms with no human intervention after the initial programming stage (Carlson, 2014; Graefe, 2016). In our perspective, this view overestimates the work performed by programmers and makes invisible the complex sociotechnical network mobilized in journalistic tasks automation, which includes several human and non-human actors. It can be argued that automated journalism involves intricate ecosystems under formation, where journalists are part of multidisciplinary teams, working alongside professionals with complementary skills, such as programmers, engineers, data analysts and designers.

In an effort to demonstrate these complex networks that engender automated journalism and make visible the humans’ role in the technology’s development, this research describes and analyzes five initiatives in Brazil where NLG is used to process large volumes of data and give insights for journalists.

These Brazilian “robot reporters” follow a different logic of those adopted by newspapers from North America, Europe and Asia, because they do not write any automated story but focus on processing open data and creating alerts published in social media platforms.

The five cases in this study are not created by great enterprises, but instead are developed by crowdsourcing teams or digital native newsrooms comprised with data journalism. These particular uses of NLG in Brazilian journalism demonstrate how technology systems are hybrid objects shaped by social, cultural and political issues and have multiple uses depending on the context they are inserted (Haraway, 1987; Winner, 1977). Inspired by the anti-essentialist lenses of science and technology studies (Callon, 1990; Latour, 2005; Law, 1992; Sismondo, 2010), one can understand technological artifacts as occasional and temporary products directly related to a given network of actors and the circumstances of their production, which are shaped by but also shape the world to which they belong.

This study seeks to investigate the role played by professionals in the development of NLG systems applied in journalism and which are the technologies and objects mobilized in the production of automated content. Our methodology includes semi-structured interviews and information collected in news and online digital platforms, intending to identify the actors assembled in these five case studies. Our study is inspired by the Cartographic Method (Barros & Kastrup, 2012) and the Cartography of Controversies (Venturini, 2010), a method of “crafting devices to observe and describe social debate especially (…) around technoscientific issues” (p. 258) and “face the highest complexity without the slightest simplification” (p. 263).

Our methodological choices aim to give visibility to professionals involved in the development, implementation, and monitoring of these initiatives, demonstrating the need of a broader concept that recognizes the role played by humans in the carrying out of automated journalism. For this study, the researchers collected information, interviewed journalists and other professionals involved, and systematized data of five different robots: 1) Da Mata Reporter; 2) Rosie from the ‘Serenata do Amor’ operation; 3) Colaborabot; 4) Rui Barbot from Jota; and 5) Fatima from Aos Fatos checking agency. In common, these initiatives use AI algorithms to process large volumes of data, automate journalistic tasks, and distribute information and interact with users through digital media platforms.

‘Journalisms,’ Artificial Intelligence and Platforms

The idea of “hegemonic journalism” refers to a set of relatively recent norms and values that govern the news environment—late 19th century and first decade of the 20th century—and the borders of which is to be considered “professional journalism” is constantly policed by the community on both sides of the ideological spectrum (Nerone, 2015). For Nerone, journalism is an “ism”—”an assemblage of ideas and norms constructed and deployed historically to make sense out of and discipline the news environment by identifying practitioners and assigning them responsibilities” (p. 314). Today there are “journalisms,” in the plural, due to the coexistence of several types of journalism with different functions and objectives in the media ecosystem. This proliferation is one of the consequences of what Nerone calls the “journalism’s crisis of hegemony,” along with transformations presented by the internet. For him, this crisis relates to the increasing incapacity of hegemonic media representing and speaking on behalf of society: “When the ‘crisis’ came, of course, everyone blamed the Internet, but this neglects just how deep the problems of hegemonic journalism have run” (p. 324).

For Jácome (2020), the normative discourse—the base for this “ism”—promotes a conception of the journalistic practice linked to operational values and procedures. “Faced with the complex materiality of the journalistic phenomena, what is perceived is the adoption of a perspective that seems to advocate a narrow and totalizing conception of what should, or should not, be considered as belonging to this ‘ism’” (p. 37, translated by authors). This generates a gap between idealized journalism and practices and processes that are effectively done through history, making “their utopian promises anchored in the very utopia they defend, projecting a future that has never realized” (Jácome, 2020, p. 273, translated by authors).

In this study, journalism is identified as a “singular collective” (Jácome, 2020) whose strength anchors in the articulation between rhetoric, actors, commercial interests and materialities: “Journalism ceases to be an object limited to a set of themes and concepts and becomes a phenomenon of mediation of time and in time” (p. 277). Jácome’s conception helps us think about Artificial Intelligence’s role in journalistic practice, and in our case studies.

The use of AI in journalism has been identified as: robot reporter (Carlson, 2014), algorithmic journalism (Dörr, 2015), machine written news (Van Dalen, 2012), automated news (Carreira, 2017) and automated journalism (Carlson, 2014; Graefe, 2016). Carlson (2014) defines automated journalism as “algorithmic processes that convert data into narratives news texts, with limited to no human intervention beyond the initial programming choices” (p. 1). Graefe (2016) conceptualizes it as “the process of using software or algorithms to automatically generate news stories without human intervention—after the initial programming of the algorithm” (p. 14). Dörr (2015) proposes a more elaborated definition acknowledging algorithms are not capable of generating texts without human interference but argues that “the direct and active human element during the process of content creation is eliminated in algorithmic journalism (…) the individual journalist in NLG is changing to a more indirect role (Napoli 2014) before, during and after text production” (p. 9), suggesting a growing need for programming skills in journalistic work.

These three definitions by important scholars in the area limit human action in automated journalism to the programming phase. It can be considered a technocentric and simplified view that makes invisible human and non-human actors involved in the process, dazzling the non-static and complex network of agents that composes these processes. It can be argued that it overestimates the programmers’ role and overshadows professionals who also work in the development, implementation, monitoring and maintaining these NLG software running on a daily basis, which contributes to a negative view and fear among journalists.

Inspired by STS and Actor-Network Theory (Callon, 1990; Latour, 2005; Law, 1992; Sismond, 2010; Winner, 1978), it can be considered that automated journalism is more than just a new technology introduced in newsrooms. One can argue that a new ecosystem is being built composed by multiple professionals working together in multidisciplinary teams to automate simple and repetitive tasks, saving journalists’ time to be dedicated in roles that cannot be automated.

However, as algorithms, these robots are not inert intermediaries or tools at journalists’ service, but agents that influence and mediate actions in the networks where they belong. This topic has been discussed by scholars of Critical Algorithm Studies. (Gillespie, 2014; Introna, 2016; Kitchin, 2017). As Introna (2016) points out, algorithms are “the computational solution in terms of logical conditions (knowledge about the problem) and structures of control (strategies for solving the problem), leading to the following definition: algorithms = logic + control” (p. 21). Algorithms’ agencies have normative implications, because they implement and construct power and knowledge regimes (Kitchin, 2017). As Bucher explains, they are not only modeled “on a set of pre-existing cultural assumptions, but also on anticipated or future-oriented assumptions about valuable and profitable interactions that are ultimately geared towards commercial and monetary purposes” (2012, p. 1169).

Moreover, algorithms are inert entities without their databases, and those have to be “readied for the algorithm” (Gillespie, 2014) which means data has to be categorized, organized, cleaned and valued to be autonomously readable by them. As argued by Gitelman and Jackson, “raw data is an oxymoron” (2013, p. 2) due to all mediation involved even before it is stored in databases.

Our perspective is closer to the scholarship of Human-Machine Communication (HMC) defined as “an emerging area of communication research focused on the study of the creation of meaning among humans and machines” (Guzman & Lewis, 2020, p. 71). This perspective proposes to analyze the interactions between people and technical artifacts as “communicative subjects” and not just mere interactive objects, considering the implications for individuals and society.

It is also important to stress the role that other platforms’ materialities, besides algorithms, play in this process, considering all case studies described in this study use Twitter’s platform to circulate content produced by the robots. According to Van Dijck, Poell and de Waal (2018), today there is the construction of a “Platform Society’’ where sociotechnical artifacts gradually infiltrate and merge their actions with social practices and institutions. The dynamic and volatile process of platforms’ organization and infiltration in various segments is called “platformization,” and it refers to “the way in which entire societal sectors are transforming as a result of the mutual shaping” (p. 19). Elsewhere, it can be argued that the process of “platformization of journalism” (Jurno, 2020) occurs when these platforms offer themselves as infrastructure for journalistic production, influencing and molding journalistic practices and production. They have to increasingly adjust and adapt their work to platforms’ logic, in order to use them in their own benefit, in a constant dispute between public and economic values. These advantages can be ready-to-use software, free storage, algorithmic targeting audiences, or broad circulation between users, etc.

Distant from users’ direct experience, even being often underestimated, platforms’ actions are composed of several layers of mediation. Protocols that are hidden behind simple user-friendly, and often symbolic, interface features make the complex technology that regulate platforms and algorithms to be considered as a mere facilitator of pre-existing social activities (Van Dijck, 2012), when connectivity itself and “online sociality has increasingly become a coproduction of humans and machines” (Van Dijck, 2013, p. 33). In contrast, platforms mold content by what they allow and make possible to do by their affordances and policies, building their own “technoculture logics” (Gerlitz & Helmond, 2013; Helmond, 2015). To Gillespie (2018), “platforms are intricate, algorithmically managed visibility machines … They grant and organize visibility, not just by policy, but by design” (p. 178). Because of that, Bucher affirms that these platforms occupy a “peculiar epistemological position, where some components are known while others are necessarily obscured” (2012, p. 1172).

Methodology

In an attempt to analyze how automated journalism materializes in Brazil, this study describes five different robots that use Twitter’s platform to publish their texts. Four initiatives publish their content based on open data and one generates alerts to users while scanning fake news spread into the platform. For this study, five semi-structured interviews were conducted with six professionals involved in the development of five robots, from July 2019 to October 2020. Those interviews were conducted online and last around thirty minutes each. Three of the interviewees are journalists, two are lawyers with experience in data journalism, and one is a researcher of NLG software as a master’s student in computer engineering.

The interviews consisted of these questions:

1. How was the team involved in the development of the robot? Were many people needed? What is the challenge in terms of people management to develop a project like this?

2. Considering equipment and technologies, what was needed to put

the robot on the air? What kind of objects and structures did they have to mobilize?

3. After participating in the development of a robot, how do you see the use of technology in journalism? What kind of applications do you think would be useful for the profession?

4. What does Artificial Intelligence mean to you? Are you afraid that

technology will end the job of journalists and other professionals?

This methodology was used to give visibility to the professionals that create those technologies, in an attempt to present their different backgrounds and demystify the idea of no human action after the initial programming choices in automated journalism.

The first robot to describe is DaMataReporter, created to monitor the deforestation of Amazon. The researchers interviewed João Gabriel Moura Campos, an engineer and computer science master student at University of Sao Paulo (USP) who is part of the developing team of DaMataReporter.

The second robot is Rosie, created by a crowdsourcing operation focused on supervising the expenses of the Brazilian House of Representatives members that generates alerts on Twitter every time it finds suspicious refunds. The researchers interviewed Pedro Vilanova, a data journalist who is part of the Serenata do Amor operation since its beginning.

The third robot is called Colaborabot and is focused on generating alerts every time a transparency website maintained by the Brazilian government is off the air. The researchers interviewed the data journalist Judite Cypreste and the lawyer João Ernane, who are the developers of Colaborabot.

The fourth robot is Rui Barbot, created by Jota, a digital native newsroom specialized in covering Brazilian Justice. Rui Barbot publishes a tweet every time it recognizes a lawsuit stopped for more than 180 days at the Brazilian Supreme Court. The researchers interviewed Guilherme Duarte, a lawyer and data enthusiast who was part of the development team.

And finally, the last robot of this study is Fatima, developed by the digital native newsroom Aos Fatos with the support of the Facebook Journalism Project. The aim of Fatima is to fight against misinformation and fake news. It monitors Twitter’s feed looking for malicious news and answers the users with the checked information link. The researchers interviewed Pedro Burgos, a data journalist who created the robot after covering the U.S. elections in 2016.

@DaMataReporter and @DaMataNews

The robot DaMataReporter (@DaMataReporter) was created to monitor Legal Amazon deforestation using data retrieved from TerraBrasilis, an environmental monitoring platform created by the National Institute of Spatial Research (INPE) maintained by the Brazilian federal government. Launched in July 2020, it publishes an alert on Twitter every time new data about deforestation in the Amazon is published. The initiative also maintains a second Twitter account (@DaMataNews) in English (See Figure 1).

The DaMataReporter bot was developed by researchers from the University of São Paulo (USP) and the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG) in a team composed of computer engineers, information scientists and linguists. The project aimed to create a “Twitter profile to complement traditional journalistic work” (França, 2020), which becomes more explicit when the robot is named as “reporter” and is described on Twitter’s profile as a “Robot Journalist covering Amazon deforestation data.”

“We still don’t have a journalist in our team, but we could really use his/her help to improve our texts with the linguists,” explains computer engineer João Gabriel Moura Campos. He recognizes calling the robot a “journalist” and the tweet a “journalistic text” is an issue, considering that what the robot produces is not a journalistic story, just a lead or the headlines: “One of our purposes when designing this robot was to create a journalistic assistant. We wanted to reach this specialized audience so that they look at the data and run after that information.” He also asserts that robots cannot substitute human journalists: “Artificial Intelligence is nothing more than statistical learning. Using the term ‘intelligence’ to define it gives too much subjective character to something that is still algorithmic.”

Software’s basic programming architecture was created by Thiago Castro Ferreira in Python and runs on Amazon Web Services (AWS). The code is available on GitHub. “We set up our database based on what was scraped from INPE, we structure all the content, all the paragraphs, make the lexicals choices using the program we developed in Python, and finally the last step of computational resource that we use is the publication on Twitter’s API,” explains Moura Campos.

The interest in developing NLG resources and a library in Portuguese is one of the reasons that motivates the team to create and maintain DaMataReporter. Despite its success, the engineer complains about the bot’s engagement being hostage to the platform logic. “A positive point is the type of audience that follows us: many journalists from major vehicles, people from media and environment sectors.” However, he wishes DaMataReporter’s voice could reach more people.

@RosieDaSerenata

In the Brazilian House of Representatives, each member—or deputy—has a U.S.$8,000 budget to spend monthly on transport, accommodation and food, getting a refund of those expenses by presenting receipts. Considering the country has 513 deputies, around U.S.$50 million is spent each year with those expenses. In an effort to fight against corruption, eight young professionals, including programmers and data journalists, created the Serenata do Amor operation (www.serenata.ai) in June 2016 to supervise those costs and generate alerts for suspicious refunds.

After raising U.S.$15,000 in a crowdfunding campaign, Serenata do Amor analyzed all refunds made from 2011 to 2017 and found 5,222 irregular receipts. They sent 587 messages to the Chamber of Deputies questioning 917 expenses from 216 different deputies. However, they only received 62 answers and just 36 returned the money (Cabral, 2017). (See Figure 2).

Because of the notifications’ low response rate and considering all data was already published by the government, in May 2017 they decided to create a robot and give visibility to those irregular expenses on Twitter.

Named Rosie (@RosieDaSerenata) in an allusion to “The Jetsons”, the robot publishes alerts every time it finds suspicious refunds. Each tweet (Figure 2) quotes the deputy’s name with a link to the original document and asks Twitter’s users for help to verify if it is irregular or not.

All of the project’s files are open source and available online, which facilitates the collaboration of 600 volunteers that currently work on this project from all over the world, including journalists and researchers. “Just as our project demands transparency, we have always been transparent. If you come in today, you know exactly what was done yesterday, and it has always been that way, from the first day,” says Pedro Vilanova, a journalist who has been part of the project’s development team since the beginning.

For Vilanova, technology should always be used focusing on people: “The people who make the magic happen at Serenata operation are the people who follow Rosie, see the findings and help propagate them.” He explains that the project uses Amazon’s cloud computing service and Python programming language, which he considers computationally simple devices that do not require astronomical investment. “Being in the cloud, our technology can be installed and executed on almost any computer.”

Besides Rosie, the project has another tool named Jarbas (https://jarbas.serenata.ai/dashboard/), a database used to view and store a copy of information regarding federal deputies’ reimbursements. On this website, one can filter payments by year, name of deputy or company, by state, view only suspicious refunds and check details of the documents (Cabral, 2017). As Vilanova describes it, these are two complementary technologies and, while Rosie is the “cleaning robot that looks at the data trying to find what is dirty there,” Jarbas is the “butler who organizes everything and delivers it to Rosie.” Without Jarbas, Rosie doesn’t work.

Since August 2018, the project is part of Open Knowledge Brasil, a partnership to internationalize and inspire similar initiatives abroad (Cabral & Musskopf, 2018). Vilanova explains that the people involved in the project became activists for open data and free information, which gave them the opportunity to participate actively in discussions about open government in the Chamber of Deputies and in court.

In March 2019, Twitter’s battle against fake accounts and spam-spreading robots affected Rosie and it stopped working (Lavado, 2019). After being blocked, the developers’ team managed to regain permission to send automatic messages, but they can no longer tag politicians in the robot’s posts. According to Eduardo Cuducos, leader of the Data Science Program for Civic Innovation at the NGO Open Knowledge and one of Rosie’s developers, partial release is not a solution: “It’s a patch. But this is better than nothing.” For initiatives like this, Twitter is considered a “more open platform,” but developers complain about the lack of transparency on rules applied to differentiate “good bots” and “bad bots.” “Rosie is not bothering one or another parliamentarian in a systematic and invasive way, which is characteristic of spam,” Cuducos points out. “It is offering extremely valuable information to public administration, as well as offering an opportunity for the parliamentarian to explain himself.”

Currently, the project team is focused on communication actions to reach a bigger audience. Vilanova points out that “maintaining an active and open community for new members, connecting people from different areas of knowledge, is essential to improve the project and to bring increasingly clearer information for people to participate in public resources’ management” (Cabral & Musskopf, 2018).

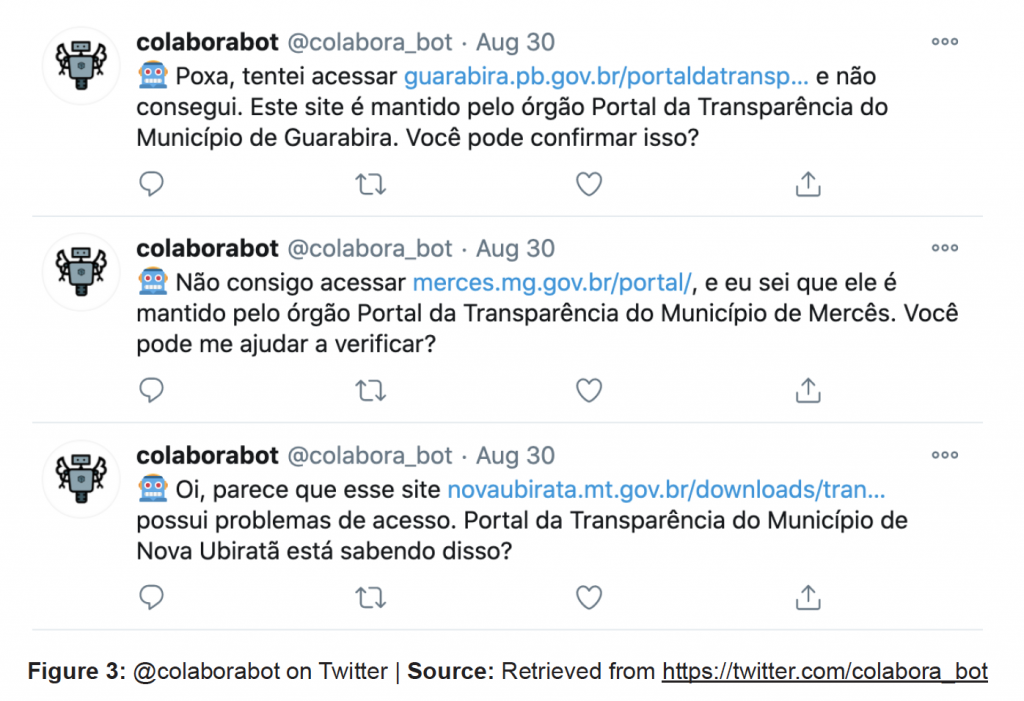

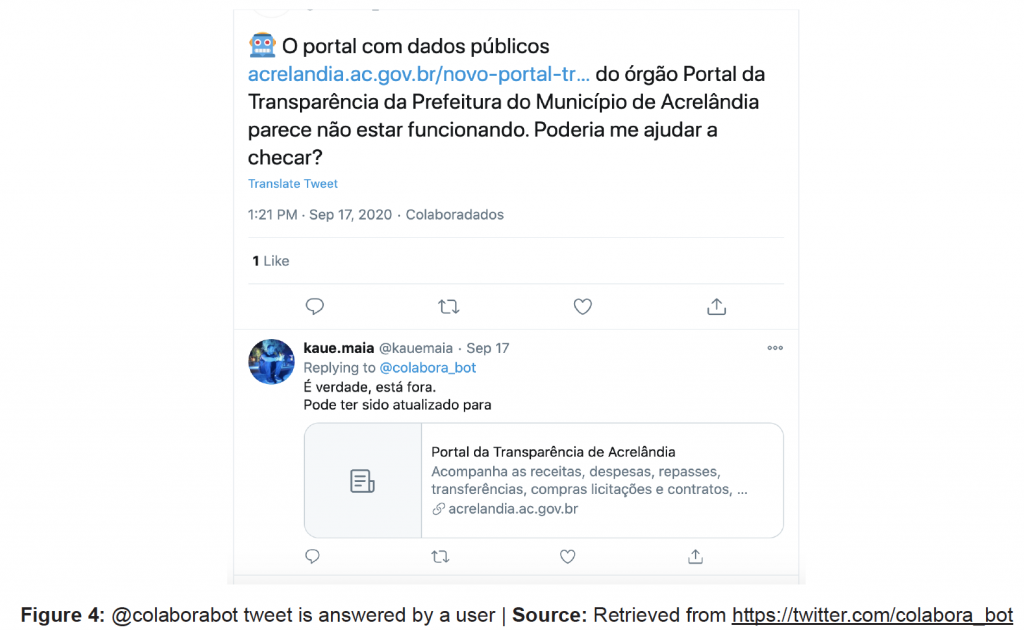

@colabora_bot

In Brazil, initiatives that support transparency and the disclosure of open data from governments are recent, considering that the access to information act, popularly known as LAI was enacted in 2012. As a project created to support access to open data and the work of journalists, Colaborabot (@colabora_bot) monitors the Brazilian government’s transparency websites, checking if they are working, and posts alerts on Twitter and Mastodon when a page is down. The robot is part of the Brazilian collaborative initiative Colaboradados, specializing in transparency and open data that describes itself as committed to veracity and easy access to information.

The concept of Colaborabot was created by data journalist Judite Cypreste when she identified that all of Brazil’s 2014 World Cup open data was deleted during an investigation she was writing for a newspaper. “When I asked those responsible, they said they were not obliged anymore to keep the site online and we had several issues to get the data back.” After this, she decided to build a robot to monitor government transparency portals and check if they are working, avoiding the recurrence of this situation and being able to forewarn in case it happens.

As shown by Figure 3, each Colaborabot tweet starts with a robot emoji followed by a small text explaining that it couldn’t access a specific transparency portal, its link and the entity it belongs to, asking users for help to check if information proceeds.

Part of the Colaborabot team, João Ernane, a lawyer and data enthusiast, was responsible for the coding. Built in Python programming language, the robot ran on a personal computer until the team earned a server as a donation. Today, Colaboradados’ team has six volunteers, including the software developer Ana Tarrisse, and all its codes are open and available on GitHub. “Using different tools, our goal is only one: make access to data and information more democratic,” explains Cypreste.

At the beginning, the development team organized a crowdsourcing campaign to create the bot’s database in which anyone could add transparency portals’ links of different cities in a Google spreadsheet. And today it covers a great part of Brazilian municipalities. According to Cypreste, “There is no one looking at this information to see if they are really available, just us. So the project is a way to keep transparency working.” (See Figure 4).

Several transparency websites already have gigantic databases, however it is common to find some of them down or deleted without previous warning. They are also difficult to monitor since some of these links change overnight “in a completely arbitrary way. They just decide to change the links and no one can find them anymore,” explains Cypreste. But sometimes they are deliberately taken down, being weeks offline, and “no one cares or gives any explanation.” As seen in Figure 4, after a Colaborabot alert, someone answered, confirming that a specific city in Brazil changed the link of its transparency page.

Colaborabot has already gone through different phases to become what it is today, not just by the project’s improvement along the way, but also considering changes that were necessary to keep it running. Some errors may also occur as, for example, sometimes links with https may work, but not with http. “Today we have a much lower error rate, because we improved the code,” says Cypreste.

Similar to Rosie from the Serenata do Amor operation, Colaborabot was also banned by Twitter in 2019 as spam, and the platform didn’t clearly explain why it happened. Colaborabot’s team realized that the problem was with the tagging system after talking with Serenata’s team. With an update of Twitter’s API, the bot could no longer tag the institutions where transparency portals were offline in its tweets exposing them to the public. “If we didn’t tag them, Twitter’s algorithm would let us continue to post. It worked, but we were unable to publish on the platform for several days,” explains Cypreste.

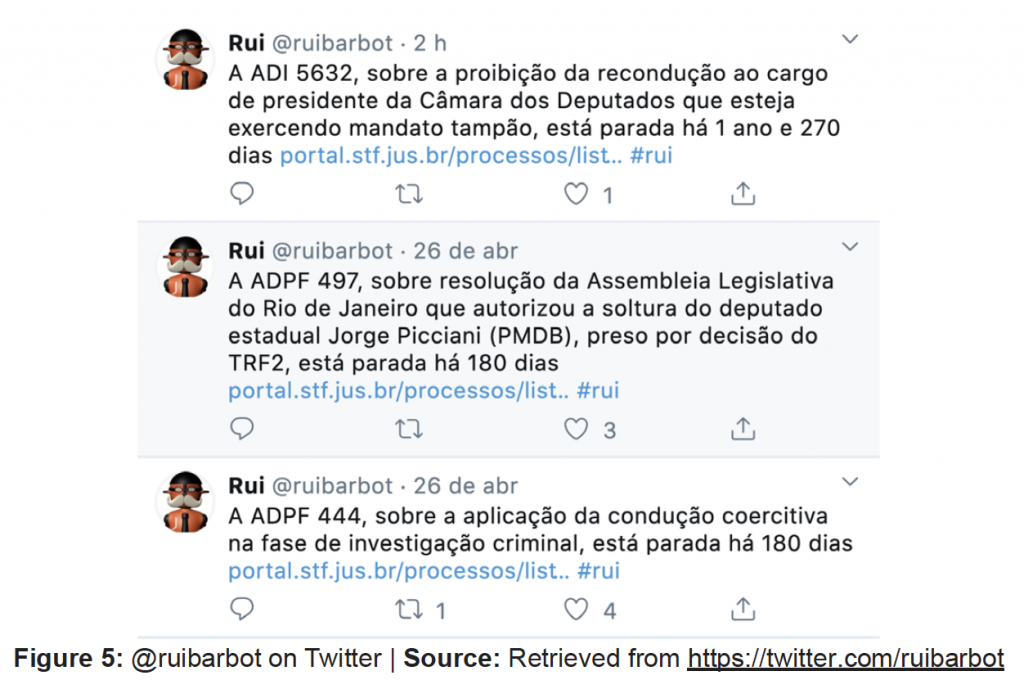

@ruibarbot

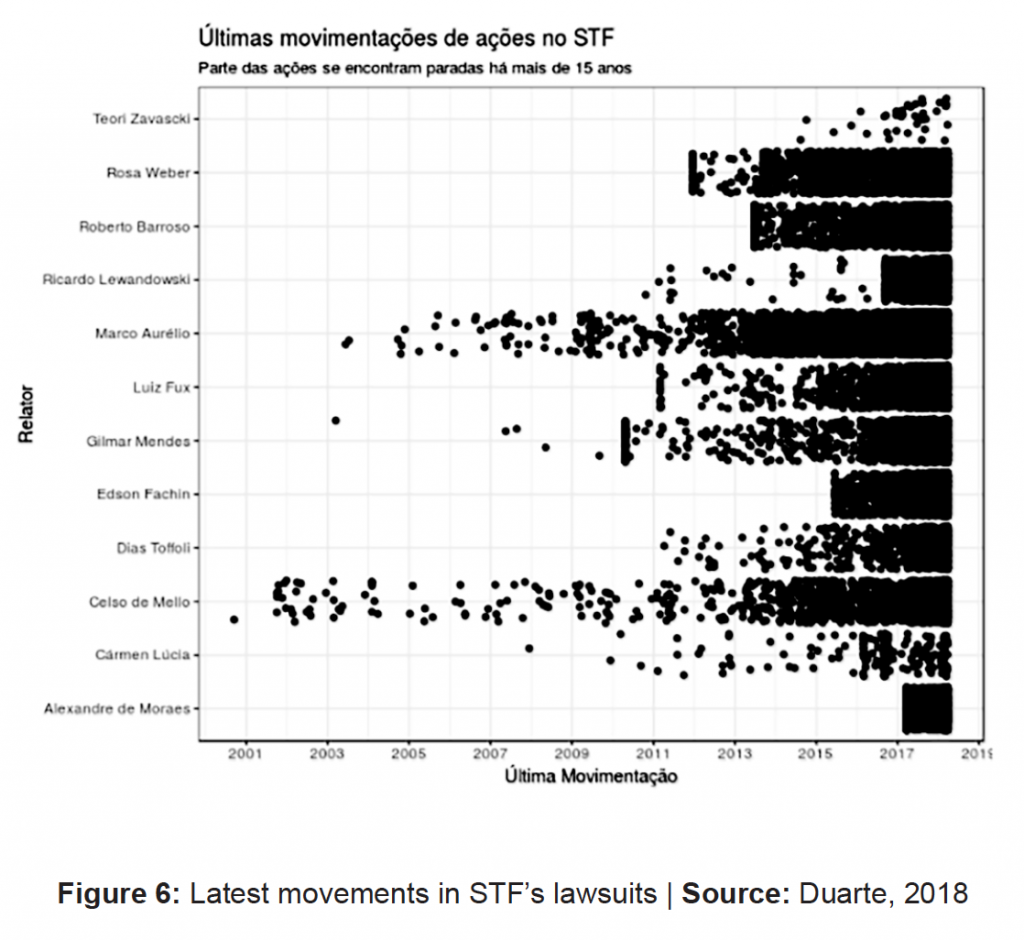

In a tribute to a famous Brazilian jurist Rui Barbosa, the website Jota (www.jota.info) specializes in legal news created by the robot Rui Barbot (@ruibarbot) to monitor lawsuits at the Brazilian Supreme Court (STF). Every time Rui detects nothing new happened in a lawsuit for more than six months, it publishes an alert on Twitter. Initially, the system was programmed to monitor 289 lawsuits previously selected by Jota journalists, based on their potential impact on society. Gradually, new processes were added to the list that is still growing. As depicted in Figure 5, each Rui tweet has a brief description of the lawsuit, how long it is stopped followed by its link to STF’s website and the hashtag #rui.

A member of the development team, Guilherme Duarte is a lawyer who also has experience as data journalist. He worked at the newspaper Estado de S. Paulo during the Panama Papers investigation before joining Jota. He explains that the system behind Rui Barbot starts with a script running in a spreadsheet on Google Drive that everyday monitors STF’s website for any updates on the preselected legal actions. “About seven days before, Rui tells Jota reporters that a lawsuit is going to celebrate its anniversary. With that, reporters can check which case is paused and prepare a story. One of the goals of this project is to bring out the importance of causes that, many times, end up forgotten.”

Currently, there are almost 36,000 legal actions at STF, which judges an average of 2.45 causes per session. As depicted in Figure 6, each black dot represents a lawsuit. On the vertical axis, one can see the name of each minister and on the horizontal axis, the years from 2000 to 2018. The dispersion of the dots shows that there are many lawsuits stopped for many years.

The original idea of creating Rui Barbot belongs to Felipe Recondo, a journalist who specialized in STF’s coverage and who has always been intrigued by the inertia where “stopped cases are infinitely more numerous than judged cases.” For him, STF’s ministers are endowed with a sovereign power that is immune of social control: they can maneuver the time. According to Recondo (2018), “the court uses the excessive volume of cases to justify or cover up its choices.’’ As Duarte explains, Recondo always pointed out that justice in Brazil does not work when it moves forward, but when it stops, because “actors act to stop lawsuits at STF.”

Committed with the transparency of the judiciary in Brazil, Rui Barbot is the result of the work of a multidisciplinary team including a lawyer, a product manager and many journalists. “Like it or not, Jota is basically made up of journalists. Rui Barbot, for example, also had the design work, the news, so it always had the participation of many people,” says Duarte. Considering the infrastructure, the project uses Microsoft Azure’s cloud computing services as a server.

@fatimabot

Created some months before Brazil’s presidential election in 2018, Fatima’s name is an abbreviation of “Fact Machine,” which is also a common name in Brazil. As a robot designed to fight against misinformation, Fatima was developed by the fact-checking agency Aos Fatos (http://www.aosfatos.org) with Facebook Journalism Project’s support.

Fatima’s aim is to provide readers with tools to check information so they can have autonomy and “feel safe to surf online in a reliable way and without intermediaries” (Aos Fatos, 2018). According to the journalist Tai Nalon, executive editor of Aos Fatos, the best way to prevent misinformation’s proliferation is to treat the insecurities of those on social media with respect. “Fátima will never say that an information is false. The goal is to give instructions, and people can draw their own conclusions” (Monnerat, 2018). The project follows the methodology created by the International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN), and Aos Fatos’ team also conducts studies to understand Brazilians’ news’ consumption and readers’ main doubts.

Officially launched in July 2018, Fátima’s profile on Twitter (@fatimabot) monitors the feed every 15 minutes. As shown in Figure 7, when detecting any tweet spreading a biased news link, it replies with an alert and Aos Fatos’ link with checked information. To maintain Fatima running, Aos Fatos’ team continuously updates a database with pre-selected biased news links that are circulating among platforms and write a correspondent fact-checking story denying the statements (Hafften, 2018).

The idea of developing a fact-checking robot came up in 2016, when the journalist and programmer Pedro Burgos worked in the United States as engagement editor at The Marshall Project. During one of the presidential election debates, Burgos predicted that Donald Trump would provide incorrect information on crime statistics, and prepared tweets with the fact checked in advance.

“The fact that I tweeted these charts just seconds after Trump spoke about the subject made a huge difference in terms of engagement, as people were more interested in the subject. This is the logic behind all successful recommendation algorithms.” (Hafften, 2018)

Back to Brazil, Burgos worked with Aos Fatos’ team to develop Fátima.

Burgos pointed out that one of the project’s biggest challenges was to deal with the subtleties surrounding the verification of facts, which is much more complex than just stating that a news content is true or false. “The ways in which users can conduct dialogue are endless, and we strive to conduct fluid and contented chat” (Aos Fatos, 2018). He also explains that the robot’s development process did not mobilize an extensive team and that an experienced programmer would be able to create its code in two days. “It took me a little longer,” Burgos reveals. “The big bottleneck today is having professionals who understand programming well enough to identify automation possibilities, and who can break a journalistic process into small tasks.”

As for infrastructure and technology, many of the services used by the development team are free and do not require large investments. For example, they used Python programming language, the code is stored on GitHub and the script runs on a virtual server that, depending on the complexity, can be the free Heroku with a cloud database on PostgreSQL. “All of this is free, and you can do a lot with this infrastructure. It is possible to put a robot to write reports based on structured data, for example, with almost zero money,” Burgos explains. However, for more sophisticated applications that use proprietary Artificial Intelligence programs, a larger investment may be necessary. “The cost and the staff depend on how fast we want the product, the amount of data we are dealing with, and the speed of processing.”

In addition to Twitter, Fátima has two other versions acting as a chatbot on Facebook Messenger since October 2018 and in WhatsApp since April 2020. In those cases, Fatima helps users to check information and if a news story is reliable or not when receiving a questionable link. It gives tips on how to distinguish news from opinion, how to find reliable data for different topics, and how to check if a source is trustworthy.

Results

The Complex Sociotechnical Networks of Brazilian Automated Journalism

Considering these five case studies of automated journalism in Brazil, one can see complex assemblages being created with multiple networks of human and non-human actors that are not contemplated in the previous definitions that put programmers in the central role of the development of those technical artifacts. Those initiatives mobilize multidisciplinary teams to keep the publishing of automated content, and the human workforce does not end after the system development.

As anticipated in the introduction, our methodological choices aim to give visibility to humans involved in the development, implementation and monitoring of these initiatives, demonstrating the need for a broader concept that recognizes the role of different professionals mobilized by those technologies. When one looks at those technologies as social and political apparatus working in a more complex network of professionals and artifacts, one can abandon the idea that NLG software could replace reporters. One can argue that the work environment in newsrooms is getting more heterogeneous, especially when it involves data-driven stories and investigative journalism.

In the past two years, there has been a movement of young professionals from different backgrounds joining initiatives related to transparency and open data as a new way of doing journalism and disseminating information with public interest in Brazil. In common, these projects use AI to process large volumes of data and use digital media platforms, mainly Twitter, as a channel to distribute information and interact with readers.

It is important to highlight that those initiatives of automated journalism in Brazil are carried out independently and four of them are committed to transparency and open data, publishing their codes on GitHub for free, for example. Rosie and Colaborabot are maintained by volunteers who keep them up and running with donations and crowdfunding resources. DaMataReporter is developed by researchers with funds from two Brazilian Universities (USP and UFMG). Finally, Fatima and Rui Barbot are managed by two digital native journalism initiatives, Aos Fatos and Jota respectively, and have a hybrid business model that combine editorial partnerships and funding support for technology projects. Thus, contrary to the most recognized examples of automated journalism worldwide, none of them are associated with traditional media companies and “hegemonic journalism.”

Most of those projects use free web services and platforms like Twitter, which is their primary channel to circulate information. Fátima is the only robot that also works on Facebook Messenger due to the partnership with the Facebook Journalism Project. Another platform used by ColaboraBot, Mastodon, “is an open source decentralized social network—by the people for the people” (Mastodon, 2020), but it does not offer the reach and audience benefits that Facebook and Twitter do.

The dependence of those bots on platforms, especially with the publication of texts using Twitter’s public API, means that they are also constantly affected by platforms’ changes and politics. As already discussed, platforms have their own interests and make constant changes on their algorithms and protocols to achieve them, mostly without publicizing it (Bucher, 2012; Gillespie, 2014; Gillespie, 2018). However, when those platforms modify their APIs, they affect the entire automated production implying that bot’s development teams have to be constantly alert to make changes and updates to keep them running. That means humans are constantly interfering in the content production process and not just in the programming stage.

Another consequence of using platforms like Twitter is that those same protocols and algorithms limit automated actions by their affordances. Rosie and ColaboraBot were banned as spam and had to change their bots in order to continue posting on Twitter: they had to stop tagging profiles in the texts. Situations like these, in which platforms block bots’ performance when identifying them as spam or negative bots are quite common in the development teams’ routines and also means that they have to be constantly working and tweaking the code to keep robots running.

Thus, it can be argued that definitions as those proposed by Carlson (2014), Graefe (2016) and Dörr (2015) are not sufficient to think about initiatives like these in Brazil. Technical artifacts are shaped by social, cultural and political issues and it is needed to contextualize them considering the entire set of actors and actions mobilized in their development. Moreover, one can reaffirm our perception that automated systems are not just tools that help journalism. They manage and reorganize a complex network of actors according to their own agency—what needs to be done for it to exist, work and continue to function based on changes in other variables. When Campos, from DaMataReporter, calls the robot “reporter” and Cypreste, from ColaboraBot, says that these initiatives are helping journalists, they demonstrate the construction of a much broader and less media centric perspective (Hepp, 2014) compared to the usual view of journalism studies.

The initiatives described in this research do not fit in the traditional sense of what would be a journalistic production, not corresponding also to any genre used to identify as journalism. Although Campos calls DaMataReporter’s tweet a “journalistic text,” we cannot say that it is a journalistic text, according to traditional molds. However, we also cannot say that it is simply an automated text: there is an informative production, with journalistic mediation and journalistic vision behind it. We cannot separate the tweet produced by the robot from the network of journalists and other professionals involved in this complex assemblage. Because of that, it can be believed that STS’s concepts and principles can help us deal with those new situations and think about heterogeneity and the actor networks under construction (Latour, 2006; Law, 1992; Van Dijck, 2012; Van Dijck, 2013; Van Dijck, Poell, & de Waal, 2018).

Furthermore, it also made us wonder if one might be witnessing the emergence of new types of “journalisms” within this myriad that already coexists in the profession (Nerone, 2015). Although there is no space for detailed descriptions of sociotechnical networks’ actors and actions, one sought to point out the several situations of agency where human actions were obfuscated by the opacity of the robots in our descriptions.

Conclusions

In this study, one can argue that the idea of automated journalism as software and algorithms that produce narratives without human intervention after the initial programming stage (Carlson, 2014; Graefe, 2016) overestimates the programmers’ work and overshadows the role done by other professionals, turning invisible a complex sociotechnical network mobilized in those initiatives. With the interviews and descriptions of five Brazilian case studies, this research can show how those initial concepts are limited and insufficient to define automated journalism and express its plurality. One can argue that innovative initiatives like these involve an intricate ecosystem under formation, in which journalists are part of multidisciplinary teams where many professionals and technologies are mobilized.

When looking at these digital infrastructures, one might have to consider their social implications and refute the idea that technology is an abstraction, because it is not a “view from above, from nowhere” (Haraway, 1987). The Brazilian case studies described above demonstrate a plurality of applications of NLG software in journalism, which are shaped by the social, political and cultural context where they belong. By helping journalists automate repetitive everyday tasks, these five robots also manage networks (Van Dijck, Poell, & de Waal, 2018) and they are not mere tools journalists use in daily work. As technical objects, they “discover” important facts, process information and act by posting it on Twitter, drawing attention to certain topics that could go unnoticed by journalists and other actors in the social debate.

These case studies also shed light to further questions about the journalistic process. If the idea of journalism is a social and professional construction (Jácome, 2020; Nerone, 2015), what does one mean by “journalism” nowadays in a media ecosystem populated by Artificial Intelligence and robots? Do these compositions change our understanding of what is “journalistic content”? Can one say automated texts published on platforms, like those stressed above, can be part of “journalistic” content?

Considering the plurality of possibilities that automated journalism can be adopted by newsrooms, this study limits its framework in just five initiatives that generates alerts on Twitter. For further research, more investigation is needed about how Artificial Intelligence is being used by other Latin America newsrooms to compare and analyze how cultural, social and political issues shape those technologies and influence its use by journalists.

References

Aos Fatos. (2018, January 4). Aos Fatos e Facebook unem-se para desenvolver robô checadora. Aos Fatos. https://aosfatos.org/noticias/aos-fatos-e-facebook-unem-se-para-desenvolver-robo-checadora/

Aos Fatos. (2018, October 1). Conheça a robô checadora do Aos Fatos no Facebook. Aos Fatos. https://aosfatos.org/noticias/conheca-robo-checadora-do-aos-fatos-no-facebook/

Aos Fatos. (2020). Nossa Equipe. Aos Fatos. https://www.aosfatos.org/nossa-equipe/

Barros, L. P., & Kastrup, V. (2012). Cartografar é acompanhar processos. Tedesco, S. et al. Pistas do método da cartografia: Pesquisa-intervenção e produção de subjetividade. Porto Alegre: Sulina. 52-75.

Bucher, T. (2012). Want to be on the top? Algorithmic power and the threat of invisibility on Facebook. New Media & Society, 14(7), 1164–1180.

Bucher, T. (2018). If… then: Algorithmic power and politics. Oxford University Press.

Cabral, F. B. (2017, April 5). Serenata de amor: Para não ser um amor de verão. Medium. https://medium.com/data-science-brigade/serenata-de-amor-para-não-ser-um-amor-de-verão-7422c9e10fa5

Cabral, F. B. (2017, June 7). Jarbas apresenta todas as suspeitas da robô Rosie da Operação Serenata de Amor. Medium. https://medium.com/data-science-brigade/jarbas-apresenta-todas-as-suspeitas-da-robô-rosie-da-operação-serenata-de-amor-cd021e9be045

Cabral, F., & Musskopf, I. (2018, August 28). Serenata entra em nova fase. Nós também. Medium. https://medium.com/serenata/serenata-entra-em-nova-fase-nós-também-6da385be216b

Callon, M. (1990). Techno-economic networks and irreversibility. The Sociological Review, 38(1), 132–161.

Carlson, M. (2014). The robotic reporter: Automated journalism and the redefinition of labor, compositional forms, and journalistic authority. Digital Journalism, 3(3), 416–431.

Carreira, K. A. C. (2017). Notícias automatizadas: A evolução que levou o jornalismo a ser feito por não humanos. (Dissertação de Mestrado em Comunicação Social) Universidade Metodista de São Paulo, São Paulo.

Clerwall, C. (2014). Enter the robot journalist: Users’ perceptions of automated content. Journalism Practice, 8(5), 519–531.

Costa, C. H. (2018, September 28). Laura Diniz fala sobre inovação e explica o trabalho do Jota. Estado de S. Paulo. https://brasil.estadao.com.br/blogs/em-foca/laura-diniz-fala-sobre-inovacao-e-explica-o-trabalho-do-jota/

D’Andréa, C., & DalBen, S. (2017). Redes Sociotécnicas e Controvérsias na redação de notícias por robôs. Contemporânea – Revista de Comunicação e Cultura, 1(15), 118–140.

Diakopoulos, N. (2013, December 3). Algorithmic accountability reporting: On the investigation of black boxes. Tow Center for Digital Journalism, Columbia Journalism School, New York, NY.

Diakopoulos, N. (2013). Algorithmic accountability reporting: On the investigation of black boxes [A Tow/Knight Brief]. https://towcenter.columbia.edu/news/ algorithmic-accountability-reporting-investigation-black-boxes

Dörr, K. N. (2015). Mapping the field of Algorithmic Journalism. Digital Journalism, 4(6), 700–722.

França, L. (2020, August 4). Robô jornalista publica no Twitter alertas sobre desmatamento da Amazônia. UFMG. https://www.ufmg.br/copi/robo-jornalista-publica-no-twitter-alertas-sobre-desmatamento-na-amazonia/

Gerlitz, C., & Helmond, A. (2013). The like economy: Social buttons and the data-intensive web. New Media & Society, 15(8), 1348–1365.

Gillespie, T. (2014). The relevance of algorithms. In P. Boczkowski, K. Foot & T. Gillespie (Eds.), Media Technologies (pp. 167–194). The MIT Press.

Gillespie, T. (2018). Custodians of the Internet: Platforms, content moderation, and the hidden decisions that shape social media. Yale University Press.

Gitelman, L. (2013). Raw data is an oxymoron. The MIT Press.

Gitelman, L. & Jackson, V. (2013). Introduction. In Gitelman, L. (Ed.) (2013). Raw data is an oxymoron. MIT press.

Glahn, H. R. (1970). Computer-produced worded forecasts. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 51(12), 1126–1131.

Graefe, A. (2016). Guide to automated journalism. Tow Center for Digital Journalism. https://academiccommons.columbia.edu/doi/10.7916/D8QZ2P7C/ download.

Graefe, A., Haim, M., Haarmann, B., & Brosius, H. B. (2018). Readers’ perception of computer-generated news: Credibility, expertise, and readability. Journalism, 19(5), 595–610.

Guzman, A. L., & Lewis, S. C. (2020). Artificial intelligence and communication: A Human–Machine Communication research agenda. New Media & Society, 22(1), 70–86.

Hafften, M. V. (2018, October 7). Robô Fátima dissemina informações verificadas no Brasil. IJNET. https://ijnet.org/pt-br/story/robô-fátima-dissemina-informações-verificadas-no-brasil

Haim, M., & Graefe, A. (2017). Automated news: Better than expected? Digital Journalism, 5(8), 1044–1059.

Haraway, D. (1987). A manifesto for cyborgs: Science, technology, and socialist feminism in the 1980s. Australian Feminist Studies 2(4), 1–42, DOI: 10.1080/08164649.1987.9961538

Helmond, A. (2015, July-December). The platformization of the web: Making web data platform ready. Social Media + Society, 1(2), 1–11.

Hepp, A. (2014). As configurações comunicativas de mundos midiatizados: pesquisa da midiatização na era da “mediação de tudo”. Matrizes, 8(1), 45–64.

Introna, L. D. (2016). Algorithms, governance, and governmentality: On governing academic writing. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 41(1), 17–49.

Jácome, P. P. (2020). A constituição moderna do jornalismo no Brasil. 1 ed. Curitiba: Appris.

Jurno, A. (2020). Facebook e a plataformização do jornalismo: Uma cartografia das disputas, parcerias e controvérsias entre 2014 e 2019. Tese de doutorado, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brasil.

Kitchin, R. (2017). Thinking critically about and researching algorithms. Information, Communication & Society, 20(1), 14–29.

Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the social: An introduction to actor-network-theory. Oxford University Press.

Lavado, T. (2019, March 1). Regras do Twitter afetam robôs que monitram políticos e órgãos. G1. https://g1.globo.com/economia/tecnologia/noticia/2019/03/01/regras-do-twitter-afetam-robos-que-monitoram-politicos-e-orgaos-publicos.ghtml

Law, J. (1992). Notes on the theory of the actor-network: Ordering, strategy, and heterogeneity. Systems Practice, 5(4), 379–393.

Lewis, S. C., Guzman, A. L., & Schmidt, T. R. (2019). Automation, journalism, and human–machine communication: Rethinking roles and relationships of humans and machines in news. Digital Journalism, 7(4), 409–427.

Linden, C. G. (2017). Decades of automation in the newsroom. Digital Journalism, 5(2), 123–140, DOI: 10.1080/21670811.2016.1160791

Monnerat, A. (2018, January 5). Bot conversacional vai ajudar a combater notícias falsas nas eleições do Brasil. Blog Jornalismo nas Américas. https://knightcenter.utexas.edu/pt-br/blog/00-19140-bot-conversacional-vai-ajudar-combater-noticias-falsas-nas-eleicoes-do-brasil

Nerone, J. (2015). Journalism’s crisis of hegemony. Javnost-The Public, 22(4), 313–327.

O’Neil, C. (2016). Weapons of math destruction: How big data increases inequality and threatens democracy. Broadway Books.

Operação Serenata de Amor. (2020). FAQ. Operação Serenata de Amor. Retrieved November 4, 2020. https://serenata.ai/en/faq/

Recondo, F. (2018, April 24). Jota lança robô Rui para monitorar tempo que STF leva para julgar processos. Jota. https://www.jota.info/dados/rui/prazer-rui-barbot-24042018

Reiter, E., & Dale, R. (2000). Building natural language generation systems. Cambridge University Press.

Sismondo, S. (2010). An introduction to science and technology studies (vol. 1). Wiley-Blackwell.

Van Dalen, A. (2012). The algorithms behind the headlines, Journalism Practice, 6(5-6), 648–658.

Van Dijck, J. (2012). Facebook as a tool for producing sociality and connectivity. Television & New Media, 13(2), 160–176.

Van Dijck, J. (2013). Facebook and the engineering of connectivity: A multi-layered approach to social media platforms. Convergence, 19(2), 141–155.

Van Dijck, J., Poell, T., & de Waal, M. (2018). The platform society: Public values in a connective world. Oxford University Press.

Veja Rio. (2018, July 19). Conheça Fátima, a robô que alerta os usuários que publicam notícias falsas. Veja Rio. https://vejario.abril.com.br/cidades/conheca-fatima-a-robo-que-alerta-os-usuarios-que-publicam-noticias-falsas/

Venturini, T. (2010). Diving in magma: How to explore controversies with actor-network theory. Public Understanding of Science, 19(3), 258–273.

Winner, L. (1978). Autonomous technology: Technics-out-of-control as a theme in political thought. The MIT Press.

Silvia DalBen, Media researcher at R-EST Sociotechnical Network Studies at the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG / Brazil) and PhD student at University of Texas at Austin (2021-2025). Lecturer at UNA University Center (Brazil). Earned a Master’s degree in communication (2018) at the Federal University of Minas Gerais researching automated journalism, and her dissertation won Adelmo Genro Filho Award granted by SBPJor—Brazilian Association of Researchers in Journalism. Bachelor degree in Journalism and in Radio and Television from UFMG, with an Exchange Program at the University of Nottingham (UK). Work: https://ufmg.academia.edu/SilviaDalben

Email: dalben.silvia@gmail.com.

Amanda Chevtchouk Jurno, PhD and Master’s in Communication from the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG/ Brazil). Academic researcher and professor, she is also a journalist graduated by the same university. As a researcher, she is interested in discussing platforms, algorithms and technologies and their interfaces with communication and journalism, focusing on the social and ethical influences of their agencies. In her PhD dissertation she discussed the platformization of journalism by Facebook between 2014-2019. Media researcher at R-EST Sociotechnical Network Studies (R-EST/UFMG) and at Group on Artificial Intelligence and Art (GAIA/USP).

Work: amandachevtchoukjurno.academia.edu.

Email: amandajurno@gmail.com.