April 13, 2017 | Registration

Solutions Journalism: Pre-ISOJ workshop teaches how to shift focus of reporting from problems to problem solving

In 2014, journalist Meg Kissinger wrote a series called “Chronic Crisis” — an in-depth examination of Milwaukee’s mental health system. But Kissinger didn’t just write about the problem, she provided a solution.

That’s the main focus of the Solutions Journalism Network (SJN), an independent nonprofit founded in 2013 that uses educational tools and advising events to train journalists to shift the focus of reporting from problems to problem solving.

Samantha McCann, director of communities for SJN, said that journalists are often trained to find the problems plaguing society, but aren’t told to focus on providing their readers with a solution.

“The modern understanding of journalism is that it’s something that holds power to account,” McCann told the Knight Center. “If someone is abusing that power or something is failing, you call it out. You draw attention to it and then society is supposed to address it and fix that problem. But it doesn’t always work that way because societies need models for change. They need successful examples of what to do when something’s broken. That’s where solutions reporting comes in.”

McCann and her colleague Holly Wise, director of Journalism School Engagement at SJN, will lead a free and public workshop to train attendees on reporting solutions stories on April 20 as part of the 2017 International Symposium on Online Journalism (ISOJ). Register now.

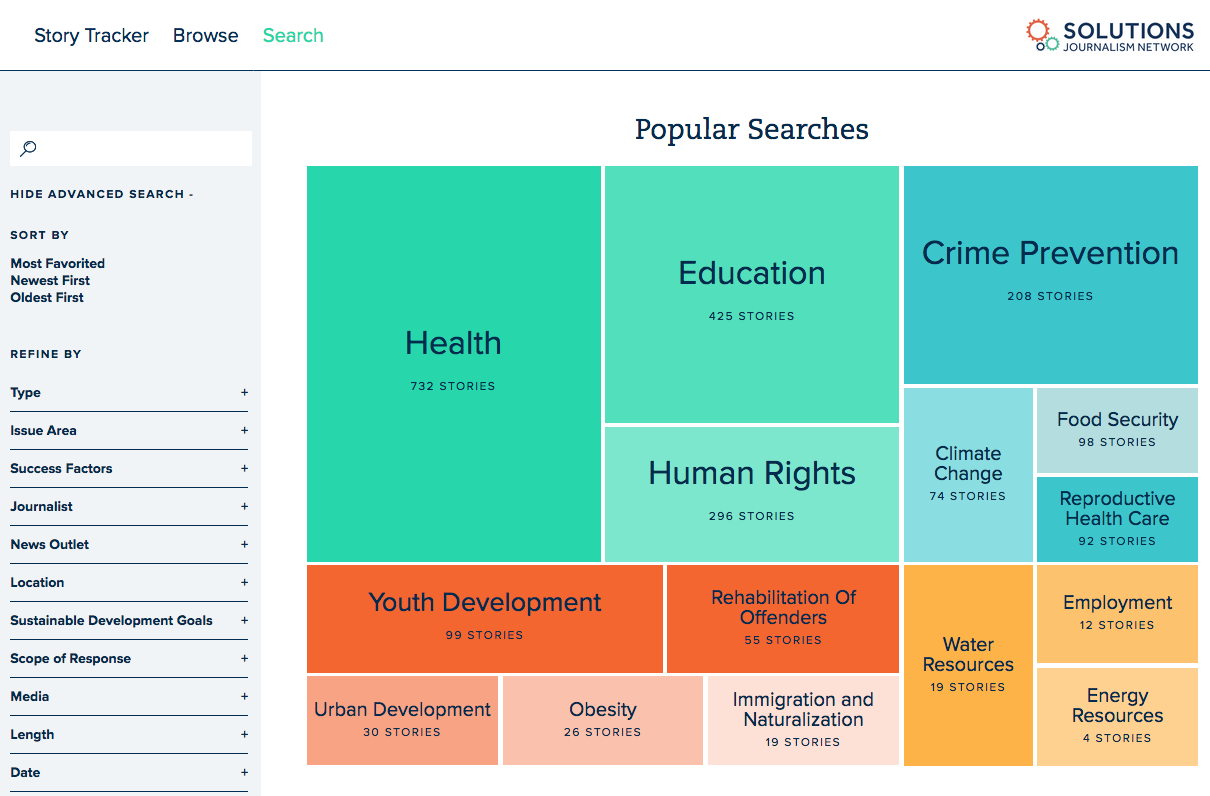

The workshop will go over the basics of solutions journalism and teach attendees the key steps of reporting solutions stories. It will also go over the Solutions Story Tracker, a searchable database of more than 1,800 stories intended to help users find different ways to approach solution-based storytelling.

Because journalists aren’t usually trained to pursue stories from a solution-oriented mindset, McCann said the simplest thing they can do to change their habits is just ask themselves one thing.

“The most powerful question you can ask to shift the entire frame of the story from a problem-focused story to a solutions-focused story is: who’s doing it better?” McCann said. “If you can figure that out, you can see what the local area can learn from that.”

But, because of the way the news cycle works, McCann said it’s usually easier to find problems than potential solutions.

“You don’t hear about the plane that didn’t crash,” McCann said. “There’s a misconception that the world is mostly full of problems and the world is mostly broken, but every problem in existence has someone already working on trying to solve it.”

If journalists can begin to change the way they approach their stories, McCann believes they can increase their impact.

“Journalism is a source of information, and if you’re providing stories that people can really use to make effective change in their communities, it can be a really powerful thing,” McCann said.

Using Meg Kissinger’s Chronic Crisis series as an example, McCann said her solutions reporting did eventually lead to positive change. After traveling to Ohio, Texas, California and Belgium, Kissinger presented her readers with different approaches to tackling mental health.

Shortly after the stories were published, the Milwaukee mayor increased funding for mental health care and abolished political control of the mental health policy board to make it a non-partisan entity with mental health experts as members.

“Meg Kissinger said that the solutions stories were absolutely key to the impact,” McCann said. “Instead of highlighting what was broken, she included this component of things that were already working to say, ‘We can move forward, we can move past this.’”

According to SJN, Kissinger said including potential solutions to the stories was what helped the community get the ball rolling to solve the issue.

“It’s one thing to talk about problems, and there are many in the Milwaukee County Mental Health System, but where the real value comes for readers is to know how does another community tackle something and turn something around,” Kissinger said.

One of the main challenges of reporting these stories simply boils down to time. Holly Wise said because journalists are usually operating on a deadline, it’s harder to prioritize finding and reporting on a solution. Beyond that, Wise said problems, not solutions, are usually what make headlines.

“There’s way more emphasis on problems and it’s through no fault of any particular journalist, it’s just how we’ve been trained,” Wise said. “We have that saying, ‘If it bleeds, it leads.’ Solutions can sometimes just be a whisper that’s hard to hear over the noise of the problems that are just screaming out.”

But after the SJN began researching the performance of solutions stories, Wise said they discovered solutions can get just as much attention as problems.

“Initial research has shown there’s greater engagement,” Wise said. “We see an increased level of engagement among our readers and among our audiences and that’s one of the reasons we do this job is to inspire engagement and make an impact.”

At the network, Wise often works with students or their professors to teach solutions journalism. With this younger generation of journalists, Wise said the idea of solutions reporting is something they really connect with.

“[Solutions reporting] really resonates with journalism students because a lot of them are by-and-large very interested in how they can use their storytelling skills to have an impact in the world,” Wise said. “This is a great way for them to showcase their storytelling skills while also making a difference.”