The Missing Piece: Ethics and the Ontological Boundaries of Automated Journalism

By Colin Porlezza and Giulia Ferri

[Citation: Porlezza, C. & Ferri, G. (2022). The missing piece: Ethics and the ontological boundaries of automated journalism. #ISOJ Journal, 12(1), 71-98]Over the last couple of years, artificial intelligence and automation have become increasingly pervasive in newsrooms, permeating nearly all aspects of journalism. Scholars have highlighted both the potentials and pitfalls of these technologies, both when it comes to the changing nature, role and workflows of journalism and the way they affect the dynamics between humans and machines as editorial decisions are increasingly determined by algorithms. The way news automation is understood by journalism scholars and practitioners raise important ontological questions about both the impact of these technologies, but also about new communication scenarios and the social connotation of news automation. Drawing on Helberger’s (2019) normative and Just and Latzer’s (2017) algorithmic construction approach, this research aims to investigate the opportunities and challenges of automation in the light of the ontological understanding by experts in the field of journalism. Analyzing data gathered from the research project “Journalism innovation in democratic societies,” the findings show that opportunities are often seen in economic terms, while ethical issues are completely ignored.

On October 27, 2021, the London-based website PressGazette, a trade magazine that offers industry-related news about digital media, published an article by one of its commercial partners, “United Robots,” about the potentials of news automation, entitled “Automated journalism: Journalists say robots free up time for deeper reporting” (Campbell, 2021). The piece offered a boosting overview of how Scandinavian news publishers have been using automation in their newsrooms, which is not surprising given that United Robots is among the main companies that have delivered news automation programs to Swedish news media groups since 2015. The author concludes the article on a highly positive note:

As of October 2021, Scandinavian—specifically Swedish and Norwegian—publishers use news robots a lot more extensively than the news publishing industry in other markets. As a result, journalists are familiar with the technology and its benefits in the newsroom. With news media in countries beyond Scandinavia now increasingly deploying robot journalism, I believe the talk we used to hear, of content automation as a threat, will shift to a focus on the opportunities and benefits that automating routine reporting can bring to newsrooms. (paragraph 10)

While the article offers a slanted evaluation of news automation, it resonates to a certain extent with industry-wide perceptions. In one of the largest studies carried out, Beckett (2019, p. 7) found that “some of the hopes and fears are based on false premises and conjecture” when it comes to news automation. In addition, a fifth of the respondents declared that they are not particularly concerned by the ethical and ontological challenges linked to the implementation of automation, and that they are far more excited by the impact that artificial intelligence (AI) and automation will have in the news industry (idem, p. 53).

AI, algorithms, and machine learning are increasingly becoming part of newsrooms, influencing nearly every aspect of journalism (Zamith, 2020). Both the pervasiveness (Thurman, Lewis & Kunert, 2019) of these innovative tools as well as their disruptive potential in restructuring newswork and professional roles become thus central elements worth of studying (Lewis et al., 2019). Even more so as the pervasiveness of automation entails new relational and communicative dynamics in the newsroom (Wu, Tandoc & Salmon, 2019), but also when it comes to the relation with the audience (van Dalen, 2012). This process leads to the creation of a new hybrid scenario (Diakopoluos, 2019; Porlezza & Di Salvo, 2020), in which traditional human–machine relationships are rewritten from the perspective of algorithms, which can be seen on the most basic level as problem-solving mechanisms (Just & Latzer, 2017, p. 239). Several researchers have already highlighted the potentials and pitfalls of this automated turn—such as in the case of journalistic authority (Carlson, 2015; Wu et al., 2019), the internal organization of newsrooms (Thurman, Dörr & Kunert, 2017), or ethical issues (Dörr & Hollnbuchner, 2016).

However, the implications of automation go far beyond the boundaries of organizations, also affecting the public sphere: Issues of accountability, transparency, and governance (Aitamurto et al., 2019; Graefe et al., 2016; Weber et al., 2018) raise important questions about the ontological roles attributed to AI and automation in the editorial process (Ananny, 2016). This study is grounded on a theoretical framework that rests on two pillars: first, it includes Helberger’s (2019) normative approach that she developed in relation to news recommenders. According to her, “the power to actively guide and shape individuals’ news exposure also brings with it new responsibilities and new very fundamental questions about the role of news recommenders in accomplishing the media’s democratic mission” (Helberger, 2019, p. 994). Algorithms and AI have therefore crucial implications on journalism’s role in society and democracy. The second pillar is represented by Just and Latzer’s (2017) algorithmic construction approach, in which they discuss how algorithmic selection has become a significant element in shaping realities, thus affecting our perception of the world. Helberger (2019) and Just and Latzer’s approach are thus compatible in that both frameworks argue that algorithmic selection exert an impact on social reality.

Based on these theoretical frameworks, this research aims to understand the opportunities and challenges of news automation, focusing in particular on the relevance that ethical and democratic challenges have on the ontology of the journalism profession. Taking into account that journalism’s relationship with technological innovations has been extensively investigated (Boczkowski, 2004; Reich, 2013), with differing positions regarding the opportunities and challenges of their implementation (Gynnild, 2014; Pavlik, 2013; Wahl-Jorgensen et al., 2016), the purpose of the project is to evaluate, from a perspective of the news media’s democratic role, the place of these technologies in the “social dynamic of news production and news consumption” (Lewis, et al., 2019, p. 421). Our study wants therefore to shed light on the following research questions:

RQ1: What kind of opportunities and challenges does automation pose for the democratic role of news media?

RQ2: To what extent are ethical issues mentioned by experts?

RQ3: What kind of ontological issues arise in relation to the implementation of automation?

The data for the analysis was obtained through qualitative interviews in five different countries (Austria, Germany, Spain, Switzerland, United Kingdom), in which 20 experts from the news industry (journalists, editors and media managers) and academia (journalism scholars) were asked about the 20 most important journalistic innovations in the last decade. Overall, more than a thousand innovations have been collected, of which 56 were directly related to news automation or AI. Through a comparative approach, the study seeks to understand the democratic relevance of journalism innovations. Within this larger framework, experts’ legitimization strategies with respect to news automation were analyzed, focusing in particular on the ethical and ontological considerations of this particular innovation.

This contribution is relevant for two reasons: first, the analysis offers specific insights about how journalism is seen in the light of new technological innovations such as AI. While ethical issues of news automation have been studied before (e.g. Dörr & Hollnbuchner, 2016; Rydenfelt, 2021), it has never been questioned to what extent automation represents an ontological issue, in particular when it comes to innovations. Second, the study offers an empirically grounded framework that offers and interpretative filter through which it is possible to assess the social and democratic impact that comes with news automation (Lewis et al., 2019; Túñez-López et al, 2021). This contribution can thus contribute to a better understanding of the ethical and ontological conditions under which AI technology is (thought to be) used in journalism.

Literature Review

The continuous datafication and quantification of journalism (Coddington, 2015; Loosen, 2019; Porlezza, 2018) has not only led to structural changes in newswork (Waisbord, 2019; Zelizer, 2015), but also to a progressive epistemological reassessment of the journalistic profession (Lewis & Westlund, 2015; Splendore, 2016). In other words: both datafication and quantification, combined with the growing possibilities of AI technology, led to shifts in many different areas related to newswork. This process is made even more complex as artificial intelligence is “a term that is both widely used and loosely defined” (Brennen et al., 2018, p. 1). Here AI is understood as a computer system’s capacity to exhibit “behavior that is commonly thought of as requiring intelligence” (NSTC, 2016, p. 6). Given the quick growth—and the breadth—of the literature that looks into the impact of AI technology on journalism, the state of the art will be structured into different parts in order to segment and organize the material thematically.

Journalists and the “Technological Drama”

Lindén (2017, p. 72) showed quite early in the empirical investigations into automated journalism that the “work of journalists is empowered and supplemented, but also replaced by smart machines.” Earlier studies tended to offer a bleak vision of automation, describing it for instance as a “technological drama over the potentials of this emerging news technology concerning issues of the future of journalistic labor” (Carlson, 2015, p. 416). Van Dalen’s (2012, p. 651) investigations also revealed that journalists expected that “what can be automated, will be automated.” However, studies that are more recent showed that journalists are less concerned by the implementation of algorithms and automation, particularly when it comes to their own role perceptions (Schapals & Porlezza, 2020).

Particularly in the news industry, new digital technology is met, as Bossio and Nelson (2021, p. 1377) state, with great expectations: “The promise of technological innovation as a savior to journalism has persisted, and news media organizations have sought to restructure newsrooms, diversify content product and encourage journalists to use new digital and online tools.” Technological innovations are thus often accompanied with quasi-religious beliefs or myths about their revolutionary powers (Mosco, 2004). Artificial intelligence and automation are no exception: especially in grim economic times, the possibilities of AI in terms of making journalistic work more efficient are persistent in industry–based discourses (Beckett, 2019). Sometimes they can even fall for boosterism when AI technology is uncritically praised, even if innovation changes almost always entail potential failures, too (Steensen, 2011).

The field of automation in journalism, as well as elsewhere, is a domain of inquiry in which the relational dynamics between the actors are deeply challenged (Montal & Reich, 2016). The introduction of tools characterized up to a certain point by agency calls into question the very foundations of the journalistic system (Schmitz Weiss & Domingo, 2010), to the extent that “there is perhaps no aspect of the news production pipeline that isn’t increasingly impacted by the use of algorithms” (Diakopolous, 2020, p. 2). Automation therefore implies investigating a completely new field with new dynamics and actors, a hybrid field as Diakopolous (2019) defined it, characterized by a constant evolution of the relational dynamics between social actors (Wu et al., 2019). The fact that the field has still moving semantic and interpretive boundaries is for instance visible by different denominations that are used when it comes to news automation: automated journalism (Carlson, 2015), computational journalism, algorithmic journalism (Diakopoulos, 2014), robot journalism (Clerwall 2014), are just some of the terms that describe automation.

The Role of Technology in Journalism

However, ignoring technology when it comes to changes in journalism is complex. Zelizer (2019, p. 343) declares that “separating journalism from its technology is difficult, because journalism by definition relies on technology of some sort to craft its messages and share them with the public.” This is even truer in the case of artificial intelligence since it has become an integral part of a new media ecosystem (Ali & Hassoun, 2019), influencing the entire structure of public communication (Thurman et al., 2019). Even if these tools are now widely regarded as helpful tools to support newswork (Bucher, 2018), they have become pervasive of journalism practice (Thurman et al., 2019), to the point that “algorithms today influence, to some extent, nearly every aspect of journalism, from the initial stages of news production to the latter stages of news consumption” (Zamith, 2019, p. 1). In fact, AI supports journalists in their everyday work, but at the same time, it changes the nature, role, and workflows of journalism (Thurman et al., 2017). It therefore contributes to making “journalism in new ways, by creating new genres, practices, and understandings of what news and newswork is, and what they ought to be” (Bucher, 2018, p. 132).

What needs to be taken into account is the fact that these innovations are not only mere tools, but they are also new actors in the field (Lewis et al., 2019; Primo & Zago, 2015), setting the stage for what Diakopoulos (2019) calls “hybrid journalism,” understood as the interplay between algorithms and human journalists (Porlezza & Di Salvo, 2020). Hence, algorithms not only affect newsroom relations between humans and machines (Wu et al., 2019), but automation also raises questions with regard to the authority of journalists (Lewis et al., 2019)—not only because automation tools reshape journalistic practice, but also because they challenge human leadership in newsrooms (Carlson, 2018). The introduction of AI in newsrooms represents thus a major challenge to journalism studies because it blurs the ontological divide between the human and the machine (Gunkel, 2012; Wu et al., 2019), even more so it questions what it means to be human (Turkle, 1984). In fact, with “the emergence of algorithmic journalism, the human journalist—the individual—is not the major moral agent anymore as other actors, journalistic and non-journalistic, are involved in news production on various levels, e.g. algorithms with delegated agency, media organizations, programmer/service providers of NLG or data collectors” (Dörr & Hollnbuchner, 2017, p. 414). The individual, human journalist becomes less relevant with regard to normative assumptions, while news organizations, as the major customer of AI-driven tools, become the central moral agents.

Social and Cultural Implications of AI in Journalism

In order to understand the impact of AI in journalism—as well as its challenges for journalism—it is necessary to enlarge the frame of analysis and adopt a wider lens that includes social and cultural changes in relation to technology’s dimensions in journalism. Especially when it comes to the implications of automation beyond the boundaries of newsrooms, it is relevant to investigate journalism’s understanding about new communication scenarios (Ananny, 2016) and the social connotation of news automation. In this sense, Zelizer (2019, p. 349) states:

Like other enterprises that have been transformed by digital technology, such as education, the market, law and politics, it is the enterprise—journalism—that gives technology purpose, shape, perspective, meaning and significance. […] If journalism is to thrive productively past this technological revolution and into the next, we need to do better in sustaining a fuller understanding of what journalism is, regardless of its technological bent, and why it matters.

This raises both ethical and ontological questions with regard to automated journalism. Ryfe (2019, p. 206) tackles this issue:

The single biggest challenge facing Western journalism today, and especially American journalism, is not economic or political, it is ontological. The challenge arises from this fact: there has never been a time in which more news is produced than today, yet not since the 19th century has so little of it been produced by journalists.

This is not only true for the competition for instance arising from corporate communications, but also from machines within newsrooms.

Algorithms are “self-contained processes and ‘black boxes’ but they are socially constructed” (Lindén, 2017, p. 72). Not only is the creation of algorithms subject to discussion, but the social context in which they are implemented needs to be taken into account as well. The role of journalism in democracy, which has often been the subject to criticism (Hanitzsch, 2011; Kleis-Nielsen, 2017; Meyers, 2010), is now challenged by additional epistemological and ontological questions, which call for a careful assessment of the social impact of these innovations.

Therefore, algorithms and artificial intelligence can be seen as part of an already ongoing process of re–evaluation of journalistic values, expanding questions on aspects such as transparency, data security and accountability (Ananny, 2016). Alongside these ethical assumptions, questions arise about the reliability and diversity of news, readers’ trust and readers’ ability to recognize machine–made editorial content (Graefe et al., 2016; van der Kaa & Krahmer, 2014; Waddell & Franklin, 2018). A good example to show how AI can impact newswork even if it is not used in the production of news, are machines used to moderate user comments. Wang (2021, p. 64) looked into the use of machines in the moderation of uncivil comments and hate speech: “The results indicated that perceptions of news bias were attenuated when uncivil comments were moderated by a machine (as opposed to a human) agent, which subsequently engendered greater perceived credibility of the news story.” All these issues lead to questioning the ontological assumptions underlying the implementation of these technologies in journalism (Aitamurto et al., 2019; Diakopoulos, 2020), and “how people discern between the nature of people and technology and the resulting implications of such ontological interpretations” (Guzman & Lewis, 2020, p. 80).

Algorithmic Construction of Reality

Just and Latzer (2017) have elaborated a theoretical framework that describes reality construction on the web as the outcome of algorithmic selection. Drawing on co-evolutionary innovation studies as well as institutional approaches, they assert that algorithms act as “governance mechanisms, as instruments used to exert power and as increasingly autonomous actors with power to further political and economic interests on the individual but also on the public/collective level” (Just & Latzer, 2017, p. 245). The two authors laid the groundwork to understand how algorithmic selection processes determine both media production and consumption, specifically because they shape reality construction: “Algorithmic selection shapes the construction of individuals’ realities, i.e. individual consciousness, and as a result affects culture, knowledge, norms and values of societies, i.e. collective consciousness, thereby shaping social order in modern societies” (Just & Latzer, 2017, p. 246). The central role of algorithms in a datafied information society bears a critical power that entails specific consequences for the public sphere in terms of what news is published, but also the way in which it is framed. Algorithms act therefore increasingly as gatekeepers, making autonomous decisions “as to which of the events taking place or issues being discussed receive coverage” (Napoli, 2019, p. 54). The traditional gatekeeping function carried out by (human) journalists is now undertaken by an array of technological actors that select, filter and organize, becoming thus a strategic factor in current societies (Stark et al., 2020).

Although Just and Latzer (2017) differentiate between reality construction by algorithms and by the mass media in their paper, the described effects of algorithmic selection applies nowadays to news media as well: first, algorithms provoke a strict personalization that contributes to increase society’s fragmentation and individualization through the construction of individualized realities. This personalization happens “on the basis of one’s own user characteristics (socio-demographics) and own (previous) user behavior, others’ (previous) user behavior, information on user-connectedness, and location” (Just & Latzer, 2017, p. 247). Second, the authors argue that the constellation of actors is also relevant, in the sense that private Internet services such as social media platforms dominate when it comes to the use of algorithms. However, many news organizations have adopted algorithms and AI as well when it comes to news distribution and personalization. In other words: algorithmic reality construction has become standard in the news media, too, since algorithms increasingly act as relatively autonomous agents (see for instance Leppänen et al., 2017).

Algorithmic Gatekeeping and Democracy

From both a democratic and public policy perspective, this trend highlights several risks: not only are algorithms that shape the individual reality construction opaque, but they usually elude any form of accountability. Helberger (2019, p. 1009) points out that news organizations need therefore to be aware of the “democratic values algorithmic recommendations can serve,” and to what extent they are actually able to do so. This however depends on the specific democratic perspective one follows:

In other words: there is no gold standard when it comes to democratic recommenders and the offering of diverse recommendations. This is why there is a typology of recommenders and different avenues the media can take to use the technology in the pursuit of their democratic mission. (Helberger, 2019, p. 1009)

The fate of algorithmic gatekeeping at news organizations is thus still open to debate, and much depends on the strategic goals as well as the democratic perspective news organizations have. If algorithms are employed the wrong way, they can “have potentially a detrimental effect on the public sphere, on pluralism, privacy, autonomy and equal chances to communicate” (Helberger et al., 2020, p. 1). These societal dimension of the use of AI-driven technologies in news organizations need to be taken seriously, otherwise there could be dysfunctional consequences for both the public sphere and for democracy:

Gatekeeping through AI-driven tools can not only affect individual users but also the structure of the public sphere as a whole. If algorithmic personalization is taken to the extreme, combining algorithmic gatekeeping with AI-driven content production, every news article might one day reach an audience of exactly one person. This has implications for all collective processes that form the pillars of modern democracies. (Helberger et al., 2019, p. 13)

This further evidences the ontological shift regarding the boundaries between human and machine-driven news production. It is therefore natural to ask what kind of impact they can have in the democratic consolidation of public communication (Esser & Neuberger, 2018; Túñez-López et al, 2021).

Methodology

The study was carried out as part of the project “Journalism innovation in democratic societies–JoInDemoS,” a comparative investigation into the most important journalistic innovations in recent years. The sample included five countries from different journalistic cultures and with different media systems: Austria, Germany, Spain, Switzerland and United Kingdom. Overall, the research followed a two–step methodology. First, 20 semi–structured interviews were conducted in each country with experts, from both industry and academia, to understand the main journalistic innovations of the last 10 years (2010-2020), according to the experts interviewed. In the selection of interviewees, a variety of professional profiles were sought, also taking into account criteria of gender equality, geographical diversity and age. The interviewees from academia were scholars specialized in digital journalism and technological innovations, while the representatives of the industry were either journalists or media managers of companies of different sizes. The interviewees were largely selected through snowball sampling (Becker, 1963): every country team had some initial contacts both in the industry and in academia. Every interviewee was then asked to provide up to five potential interviewees active in the area of journalism innovation. All interviewees were previously contacted by email, explaining the goal of the project, the definition of journalistic innovation and providing them with the questionnaire in advance. Overall, 108 experts (Austria: 23; Germany: 20; Spain: 25; Switzerland: 20; United Kingdom: 20) were interviewed, which resulted in a database of 1,062 innovations. The large number of experts, together with the snowball sampling, naturally causes a certain heterogeneity of actors being interviewed: they range from academics to media policy actors, journalists, editors, technologists, media managers, and entrepreneurs.

The interviews, carried out between January and May 2021, took place exclusively online due to the health emergency. However, this method did not create any problems for the project, as it is well established that online interviews can be a useful ally for the social sciences, not only during crisis times (Gray et al., 2020; Salmon, 2012; Sedgwick, 2009).

The interviewees were asked to come up with 10 successful journalism innovations that they consider to be among the most important ones in each country in the past 10 years (“Please mention if possible 10 successful journalism innovations that you consider to be among the most innovative or most important in (insert country) and whose introduction occurred at least one year ago”). Successful means that the innovation is still in progress and has achieved, from the interviewees’ perspective, a desired goal or outcome. It was also relevant to know why they mentioned the innovation in question and who was instrumental in conceiving or designing it. Follow-up questions were therefore asked to identify where the innovation is located, when it was launched, who played a major role in shaping and designing it, and who is responsible for it? The interviews also used an aided recall in the four different areas product, organization, distribution and commercialization to check for innovations that have not been mentioned before. Each of the mentioned innovations was then discussed in detail in terms of its design, development, rationale, its goal(s), as well as its implementation.

All the interviews were recorded, subsequently transcribed and catalogued into an analytical framework common to all countries. This led to the creation of an overall database in which every mentioned innovation was recorded, together with the specific quotes from the interviewees. The quotes in the database were transcribed in their original language and then translated to English by the research team in order to allow for a comparison between the countries. Each innovation was categorized according to four areas of interest: production, organization, distribution, commercialization. This section was relevant in order to understand more clearly the ontological framework that accompanies the innovations in the various countries. The innovations for each country were then ranked based on the number of mentions by the experts. The data analysis was carried out manually in each step, so no computer software was used.

In a second step, innovations related to news automation were gathered from the overall list. All those innovations that were considered by the experts to be related to AI, machine learning, or included any form of algorithm were taken into account. Once the innovations were aggregated, it was carried out a descriptive statistical analysis regarding the frequencies and the type of innovations related to news automation. Subsequently, experts’ justifications were also analyzed carrying out an inductive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2013). Initially, the interviews were analyzed, generating codes for relevant features such as the understanding of AI, rationales for using AI, concerns over its use, or the strategy news organizations adopted regarding the implementation of AI–driven tools. These codes allowed to identify meanings that lie more or less “beneath the semantic surface of the data” (Brown & Clarke, 2012, p. 61).

Emergent themes were subsequently identified based on these initial codes. The prevalence of specific themes was determined on the frequency of them being mentioned by different experts. However, as Braun and Clarke repeatedly stress (2006, p. 82), the simple frequency of a theme appearing in the data is not the only element determining the existence of a theme, but it very much depends on the researcher’s perspective. Validity measures, which certainly belong to content analyses, are therefore not common in thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2021, p. 336). This final stage also explored whether, among the different expert explanations provided in the respective countries, there were similarities both nationally and internationally. This has allowed also to identify any interpretive gaps between countries, and the general interpretive trend that accompanies the ontological recognition of automation, regardless of the social context.

Results

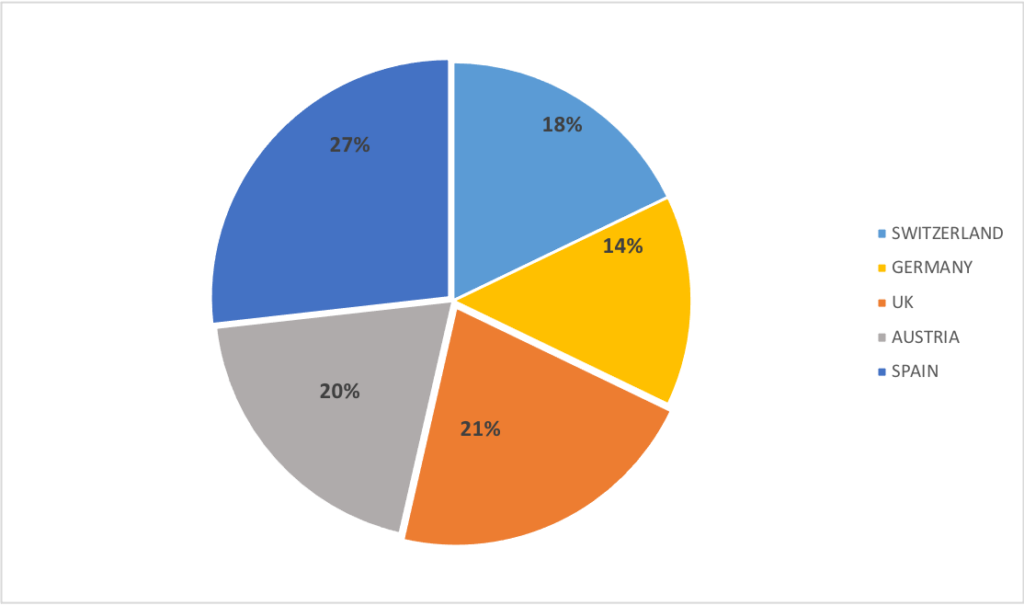

The data collected during the interviews revealed that in all five countries automation was considered to be one of the most successful innovations. Automation is mentioned as a journalistic innovation 56 times out of a total of 1,062 innovations that were gathered in all expert interviews. This is an equivalent of 5% of all the innovations mentioned. There are slight differences in the number of mentions: in Spain (15 mentions, 27%), automation is mentioned more often than in the United Kingdom (12 mentions, 21%), Austria (11 mentions, 20%), Switzerland (10 mentions, 18%), and Germany (8 mentions, 14%) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Distribution of mentions in the five countries (n=56)

What Exactly is Automation? Different Understandings and Types of Automation

When talking about automation, experts used several terms, from the more generic automated journalism, to robot journalism, to more circumscribed definitions such as artificial intelligence, algorithms and chatbots. The difficulties of finding a common label was both mentioned by scholars as well as journalists. One academic from Germany for instance stated: “I find the word a bit difficult but: robot journalism. Yes, that you can have news, just simple things like weather and sports, etc., automated there.” In Austria, a journalist focused instead more strongly on AI, mentioning a specific news organization that uses “AI approaches in forum moderation, hate bots or whatever it means. Also in general AI approaches in community building and moderation.”

However, even in the case of more circumscribed innovations such as chatbots, experts almost always refer to automation in a very broad and generalized way, without a clear nomenclature or (technical) expertise regarding the peculiarities of each innovation. This has prevented further categorization within the field of automation since there are no clear parameters for determining the various tools. The experts often referred to similar tools using different explanations, or using different explanations they were referring to similar types of automation tools. The same term can therefore be used to refer to different technological tools or practices. Some journalists, for example, describe automated journalism as an improvement in the process of personalizing content, by analyzing audience metrics algorithmically in order to offer users content in line with their interests. Others link the term to the automation of archive search or news and source–gathering programs. Others again use vague terminology such as “AI systems” or “AI approaches,” which can refer to almost any form of automation:

A Spanish startup that produces content automatically, through AI systems. There are other companies using this kind of system, but none in such a powerful way. (Journalist, Spain)

The field of interpretation is therefore still developing, particularly when it comes to the news industry representatives. Automations are characterized by a performativity and terminological malleability that does not yet allow to precisely categorize the different tools and programs that belong to the macro category of automation. At the same time, the vagueness of the descriptions demonstrate a lack of consensus around what AI encompasses in relation to newsroom innovation. This finding is consistent with what Beckett (2019) identified in his exploratory study: it demonstrates the news organizations’ high level of tinkering and experimentation around initiatives involving AI, and the often–missing AI strategy. However, by observing the fields of practical application of innovation, it is nevertheless possible to obtain useful data in order to understand the main ontological implications of automation.

Different Domains of Automation

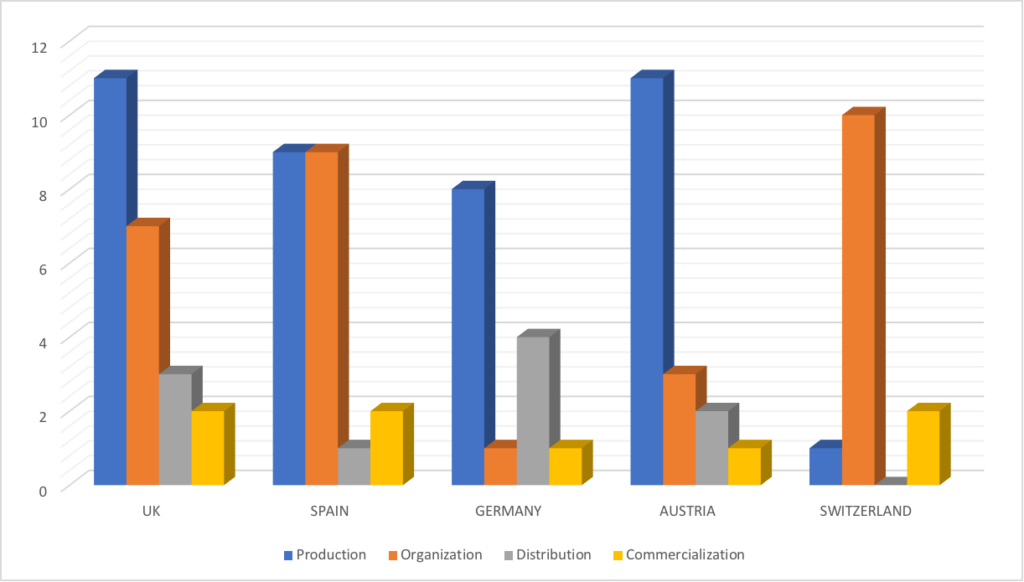

Looking at the different fields of application (production, organization, distribution, commercialization), common trends could be identified in almost all countries. In all countries’ automation is mainly associated with the fields of production and organization (see Figure 2). It is important to point out that these fields of application are not exclusive, but they are mutually influenced by each other. For instance, production, which refers to the editorial content production process (news gathering, writing and editing), is also linked to the organizational domain (newsroom structure and organizational strategy) as well as distribution, e.g. through the use of metrics, which are algorithmically analyzed or that inform news recommenders.

Figure 2 Area of innovation

Specifically, automation influences the field of production allowing, for example, the creation of artificial texts without the participation of humans (automated journalism), or the creation of news with graphics and customizations that facilitate the work of journalists. The countries that have achieved the highest range in the production field are the United Kingdom and Austria.

They are mostly used in very specific fields, like financial and sport news. But we have also experiences that instead use these tools regularly, on a large scale, on local and general news. They use big data and natural language machines on very common news. (Academic, U.K.)

[…] Artificial intelligence helps you to know what content to put behind the wall, what not to put behind the wall. (Other expert, Spain)The possibility of facilitating the work of journalists is also linked to the organizational domain, which is an area of major interest in both Switzerland and Spain. In this case, the interest is focused more on internal editorial dynamics. In all countries experts stressed how automation can make journalism more efficient by speeding up individual editorial steps, and that automation frees up additional time, allowing journalists to work on more in–depth investigations by automating routine tasks that rely on structured data.

Bots are those who are in charge of generating news that have little added value by themselves through data processing. It saves a lot of time for the newsroom regarding traffic generation, and journalists can focus on their objective of producing information. That gives us autonomy as a medium. (Journalist, Spain)

Nevertheless, the domain of distribution is, together with the commercial field, one of the least mentioned domains overall. The only exception is Germany, which has the highest range of all countries. In general, the influence of automation in regarding distribution is linked to two aspects: first, to format and content customization and personalization, a field that affects not only content production, but also its distribution to the users. A second aspect concerns community management, particularly when it comes to moderating and filtering hate speech and other forms of harmful content.

The tool is there to look for hate speech in the comments, in the webpages, in your articles and draws your attention to it. Possible hate speech is filtered out, blocked, and sent to those actors, who can react to it. But at the same time, it frees them up. (Other expert, Germany)

As far as commercialization is concerned, the interviews showed that the experts do not consider this a primary area for automation. Few interviewees mentioned content monetization, automated subscription recommendations or reducing editorial costs as areas of application, but they are not among the most influential areas for automated tools.

The use of data and AI is used for the personalization of advertising and subscription sales. It doesn’t matter whether it is advertising, for example, programmatic advertising, which has triumphed all over the world and generates the most revenue in any media, or even segmenting the audience to sell them a subscription. […] Getting more traffic and monetizing content. (Journalist, Spain)

Justifications Offered by the Experts

The ontological reasons that determine the choice of an innovation over another are a key component to understanding which role AI will play in the future of journalism and public communication. As mentioned above, the main fields of application seem to be news production as well as organizational aspects. Going into more detail in each country, and looking specifically at the experts’ justifications, we can see how the ontological matrices behind the implementation of automation have both common aspects across all countries as well as national peculiarities. We can therefore identify three main themes that emerge from the interviews with the experts, and that are present in all five countries:

- Automating “safe news”

- Making journalism more efficient

- News personalization

Almost all the country experts emphasized that AI could be used mainly in relation to so-called “safe news,” that is news with little potential for in-depth analysis mostly based on structured data. This means reporting this kind of news equals a routine job without the need for any special expertise that can quite easily be automated. This occurs often in sports or financial journalism. This dominant theme is also related to another topic common to many countries, namely saving time and costs in terms of producing information, making journalism thus more efficient. By having tools that can deal independently and without human intervention with data, transforming it into news through automation, journalists are able to concentrate on more relevant and interesting topics, where automation is more difficult to implement as human creativity is requested more strongly (although research shows that even in the area of creativity automation and AI are starting to contribute, see for instance Franks et al., 2021).

They are certainly among the most renowned innovations. They are used very well in the case of “safe” news, where the margin of error is very low. Like in sports journalism or business news. (Expert, U.K.)

Inspired by the USA, where it is also used for sports results. Where it is not a pure cost-cutting measure, it can help to free up resources so that journalists have more time for other tasks afterwards. (Academic, Switzerland)

Another aspect that emerged in several countries, albeit with different nuances depending on the specific case, is the improvement of content personalization. Not only the analysis of users’ interests, but also the best ways to present content or which news format to use are seen as the most important innovations of recent years. However, the implementation of this kind of automation is also the most complex to realize: Obtaining tools that are able to autonomously classify users through algorithms and databases, or that provide products, formats or even suggestions for content creation (how to choose headings, images or keywords) based on user metrics and expectations, is a process that implies improvements throughout all areas, from news production to organizational aspects to the distribution and marketing of content.

Besides the three main themes there are also the specificities of each country. Germany, for example, is the country with the lowest number of innovations, and the one with the highest number of innovations in the distribution domain. However, a closer look at the justifications of the experts reveals a varied picture. In addition to the already mentioned safe news, there are also tools for video transcription and translation, moderation in online forums and content personalization. The latter actually confirms the trend towards distribution, since personalization in this case is focused on the best way to distribute content to users. In other countries, personalization is mediated through the news production perspective, having therefore as main ontology the improvement of the production itself, and not the final fruition of the content.

Together with our customers, we have now begun to understand what effect which content has on which user in which context, when does he access it? Is he on the train with his smartphone or is he sitting on the sofa at home with his tablet and relaxed? We can understand all of that right now. And in the formulas today, we can then just work through algorithms and artificial intelligence. We can then make those work. Those algorithms and that’s maybe the next innovation of bringing artificial intelligence and technology into the newsroom. (Journalist, Germany)

The justifications provided by the Austrian experts, highlight a main interpretative filter: the 2020 Viennese state elections. Several respondents emphasized the usefulness of bots and algorithms in managing and updating data from the election campaign. As a result, the Austrian experts focused more on the automation of the content production.

On the evening of the election at 7 p.m., there was an automated text, not only the result, but also an automated text for all municipalities in Austria, meanwhile in Vienna also at district level and so on. And that you can look up—I live in Benno-Gasse, how did my neighborhood actually vote? (Journalist, Austria)

It should also be noted that there is an interest in the role of mediator in public forums, as in the case of Germany. This more “social” role of automation was also mentioned among Austrian respondents, but not in the remaining countries.

In the past few years, two additional tools have been built with the sponsorship of the Google News Initiative. “ForUs” took a close look at the influences of quality and design on the quality of the comments, as well as the possibility of making comments only temporarily and not indefinitely accessible on the website. The De-Escalation Bot, financed by the Google News Initiative, has also brought important insights into the use of regulating AI in forum maintenance and can predict outbreaks of escalation early enough in the future and relieve human moderation over distances. (Journalist, Austria)

The Swiss experts focused more on the organizational side, often emphasizing the editorial improvements that can be achieved. Speed and the possibility to work on more complex stories are among the main ontological inputs provided. The same perspective is offered by Spanish experts, who repeatedly stressed the importance of automation in facilitating the work of journalists by reducing the cost of labor. A particularly interesting aspect in the answers of the Spanish experts is the interest in different communication formats, mentioning also podcasts and interactive videos:

A podcast that mixes information and narration (talking about the example). It tells controversial stories about the Spanish King Juan Carlos I. And it does it in a very original way, as well as using artificial intelligence to recover or emulate the voices of people who have died, such as the dictator Francisco Franco. There is not only an innovative component in the use of the tool, but also in how they approach the topic. (Journalist, Spain)

Finally, the U.K. experts not only underlined the possibilities with regard to the transcription and translation of texts, the archiving of documents and sources, but they offered also a more holistic perspective of automation. Many of the interviewees underlined how the implementation of AI is part of a more radical and structural change in society itself, modifying not only journalism practice and news distribution, but also the authority of the journalism profession.

Data is becoming more and more important as a source of story, they assume more authority in society (like with covid, climate change. All based on data). It’s radically expanding in many different forms and fields. (Journalist, U.K.)

Automation both in terms of production, i.e. filtering information and monitoring trends, but also in terms of structured journalism, which is perhaps the most interesting aspect. A system of cooperation between machines, databases and journalists, who are required to know how to write in a new way, one that is close to the machines that reorder and organize everything. (Journalist, U.K.)

Overall, automation is still an emerging phenomenon in the journalism industry. This is reflected by the fact that experts describe automation—or artificial intelligence—generally in broad terms, referring to similar tools with different explanations. Additionally, the different domains of implementation, from information gathering to news distribution, make a common definition of automation a complex issue. The findings also show that automation, in terms of its innovative potential, is primarily attributed either to news production or to organizational aspects. Hence, the innovative potential of automation seems to be attributed more strongly to the editorial production process rather than to news distribution. The interviewees underline this aspect by highlighting the efficiency–increasing potential of AI, which includes the focus on highly structured “safe news” that can be automated without too many risks of producing inaccuracies such as sports results. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that some interviewees pointed out that the increasing pervasiveness of automation in newsrooms is just a reflection of a wider change in society that comes with a shift towards quantification and datafication.

Discussion and Conclusion

Even if there is a broad range of views, the interviewees have a common understanding of the pervasiveness of automation (Thurman et al., 2019). These findings are therefore in line with current research: news automation is not a phenomenon that is circumscribed to its manifest expressions such as automated journalism or news personalization through the algorithmic analysis of user metrics. News automation also influences the newsroom and the organizational structure, and it also entails consequences for users as well as the public sphere. It is a phenomenon of major impact that follows the previous process of datafication of journalism (Loosen, 2018; Porlezza, 2018). Eventually, algorithms have infiltrated different areas of newswork, which is reflected by the diversity of the legitimizations offered by the experts.

When analyzing the justifications for implementing AI in newsrooms, it emerged that the opportunities offered by automated tools are mainly related to issues of efficiency and (economic) resources: in the domain of news production, experts mentioned the possibility to automate “safe news,” that is to say news that can be easily automated without too much risk, saving therefore time for more interesting and complex investigations. Other examples that were mentioned, such as the creation of interactive tools or using databases, also support an ontological understanding of journalism that is mainly focused on improving the internal dynamics of the editorial staff in terms of production, organization, and distribution. This becomes particularly clear in the case of personalization, which is an example of automation that has been mentioned in previous literature as well (e.g., Helberger, 2019), where an economic logic prevails. This exclusive focus on the economic and production perspective indirectly answers to RQ1, revealing how the opportunities and issues that the introduction of AI may have on the democratic role of journalism, are not a priority for the interviewed experts. This may be justified, in part, by the fact that the experts were interviewed on the most innovative cases, which may have contributed to the dominant perspective on the automation of news production rather than the implementation of AI-driven tools in news distribution. The interviewees do not take into account any democratic issues related to AI, but in certain situations, as in the case of personalization, it can have significant and potentially dysfunctional consequences for users. Just and Latzer state that:

algorithmic selection essentially co-governs the evolution and use of the Internet by influencing the behavior of individual producers and users, shaping the formation of preferences and decisions in the production and consumption of goods and services on the Internet and beyond. (2017, p. 247)

Automation affects, therefore, the fruition of news, causing an individualized and fragmented news consumption that makes it more difficult to find common grounds and topics. But, as Helberger (2019, p. 1009) states:

So instead of simply asking whether, as a result of algorithmic filtering, users are exposed to a limited media diet, we need to look at the context and the values one cares about. Depending on the values and the surrounding conditions, selective exposure may even be instrumental in the better functioning of the media and citizens.

The automation of engagement and audience consumption data certainly helps editorial offices to read more clearly the needs of the majority of users. In addition, offering the individual citizen a product calibrated on the basis of their needs and preferences might well increase profits. However, if the algorithmic control is not well balanced, it could potentially have various consequences on the democratic role of journalism, and on its traditional public authority. Resuming Helberger’s thought on the processes of content personalization, it is important not to fall into the error of judging only positively or negatively the use of these editorial strategies, as much as assessing their relevance and coherence within the democratic context of reference, i.e., “to use AI–driven tools in a way that is conductive to the fundamental freedoms and values that characterize European media markets and policies” (Helberger et al., 2019, p. 23). A profit orientation that accompanies the implementation of automation is not in itself a problem given that news organizations are driven by profits, but if taken as the main ontological reason behind the use of AI in journalism, it can have a fallout that transcends the boundaries of newsrooms. This also answers RQ3: taking into account that algorithms and AI can become autonomous agents within newsrooms, these tools have the potential to exert a significant influence on the editorial production process, bringing up several ontological issues. Indeed, from this perspective, the question of “what journalism is, and is for, and how it is to be distinguished from an array of other news produces, is raised anew” (Ryfe, 2019, p. 206).

Regarding RQ2—”To what extent are ethical issues mentioned by experts?”—the interviewees did not raise any particular concerns, demonstrating, as in the case of the democratic role of journalism, that ethical issues are not among the main metrics for judging AI. The reasons for the missing ethical considerations can be explained in two different ways: first, methodology—the interviewees were not specifically asked about ethical concerns regarding news automation or any other journalism innovation. However, this omission was willingly chosen to offer the respondents as much freedom regarding their legitimation strategies for the different innovations, in some cases supported more by ethical–democratic motivations and in others, as in the case of automation, by profit and production reasons.

The second reason can be linked to the fact that, often, within the news industry, ethical considerations are not among the primary concerns of news organizations when it comes to the implementation of AI technology. Beckett’s (2019) research has shown that tech-savvy experts in particular are less concerned about the negative consequences of these particular innovations. However, even if the interviewees did not mention explicitly ethical issues, they specifically pointed out the pervasiveness of news automation as well as the centrality of data. Once more, the industry perspective resonates up to a certain extent with the responses from the interviewees. While the (over–)excited discourse within the news industry with regard to news automation reflects previous research, it was unexpected to see that the interviewed journalism scholars did not take a more critical stance regarding the implementation of these technologies.

This paper wanted to evaluate the relevance of ethical and democratic principles in the ontological construction of automated journalism, and by doing so circumscribed the role of news automation in the “social dynamics of news production and consumption” (Lewis et al., 2019). Drawing on Helberger’s (2019) normative approach and Just and Latzer’s (2017) algorithmic construction, professional priorities were investigated by experts in the field in light of the opportunities and challenges offered by AI. The results show that automation is often viewed through an economic lens, offering opportunities to increase the efficiency of news production, personalization, or increase time for more complex investigations. Ethics do not appear to be a primary concern, offering an ontological understanding in line with previous studies of industry perspectives.

As with all research, this study has limitations. First, ethical concerns were not specifically part of the interviews. Although this was a conscious decision in order to understand whether ethical concerns would emerge in the experts’ legitimization strategies, it could be interesting in future research to investigate whether ethical issues have become a relevant issue in newsrooms. Another limitation comes with the original orientation of the project. Given that the project was focused on journalistic innovations in general, the specific social implications of automated journalism and other forms of news automation are lacking. Future research should therefore specifically investigate the social implications of automation, particularly in terms of ethical notions such as transparency or accountability.

References

Aitamurto, A., Ananny, M., Anderson, C., Birnbaum, L., Diakopoulos, N., Hanson, M., Hullman, J., & Ritchie, N. (2019). HCI for accurate, impartial and transparent journalism: Challenges and solutions. In CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems Extended Abstracts. https://doi.org/10.1145/3290607.3299007

Ali, W., & Hassoun, M. (2019). Artificial intelligence and automated journalism: Contemporary challenges and new opportunities. International Journal of Media, Journalism and Mass Communications, 5(1), 40–49.

Ananny, M. (2016). Toward an ethics of algorithms: Convening, observation, probability, and timeliness. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 41(1), 93–117.

Beckett, C. (2019). New powers, new responsibilities: A global survey of journalism and artificial intelligence. London School of Economics.

Becker, H. S. (1963). Outsiders: Studies in the sociology of deviance. Macmillan.

Bossio, D., & Nelson L. (2021). Reconsidering innovation: Situating and evaluating change in journalism. Journalism Studies, 22(11), 1377–1381. doi:10.1080/1461670X.2021.1972328

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper et al. (eds), APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol 2: Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological (pp. 57–71). American Psychological Association

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. Sage.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 328–352.

Brennen, S. J., Howard, P. N., & Kleis Nielsen, R. (2018). An industry-led debate: How UK media cover artificial intelligence. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

Bucher, T. (2018). If … then. Algorithmic power and politics. Oxford University Press.

Campbell, C. (2021, October 27). Automated journalism: Journalists say robots free up time for deeper reporting. PressGazette. https://pressgazette.co.uk/automated-journalism-robots-freeing-up-journalists-time-not-threatening-jobs/

Carlson, M. (2015). The Robotic Reporter. Automated journalism and the redefinition of labor, compositional forms, and journalistic authority. Digital Journalism, 3(3), 416–431.

Carlson, M. (2018). Algorithmic judgment, news knowledge, and journalistic professionalism. New Media & Society, 20(5), 1755–1772.

Clerwall, C. (2014). Enter the Robot Journalist: Users’ perceptions of automated content. Journalism Practice, 8(5). doi:10.1080/17512786.2014.883116

Coddington, M. (2014). Clarifying journalism’s quantitative turn: A typology for evaluating data journalism computational journalism and computer-assisted reporting. Digital Journalism. doi:10.1080/21670811.2014.976400

Diakopoulos, N. (2015). Algorithmic accountability: Journalistic investigation of computational power structures. Digital Journalism 3(3), 398–415.

Diakopoulos, N. (2019). Automating the news: How algorithms are rewiring the media. Harvard University Press.

Diakopoulos, N. (2020). Computational news discovery: Towards design considerations for editorial orientation algorithms in journalism. Digital Journalism, 8(7), 945–967.

Dörr, K., & Hollnbuchner, K. (2016). Ethical challenges of algorithmic journalism. Digital Journalism 5(4), 404–419. doi:10.1080/21670811.2016.1167612

Esser, F., & Neuberger, C. (2019). Realizing the democratic functions of journalism in the digital age: New alliances and a return to old values. Journalism, 20(1),194–197. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884918807067

Gynnild, A. (2014). Journalism innovation leads to innovation journalism: The impact of computational exploration on changing mindsets. Journalism, 15(6), 713–730. doi:10.1177/1464884913486393

Graefe, A., Haim, M., Haarmann, B., Brosius, H-B. (2016). Readers’ perception of computer-generated news: Credibility, expertise, and readability. Journalism, 19(5), 595–610. doi:10.1177-/1464884916641269

Gray, L. M., Wong-Wylie, G., Rempel, G. R., & Cook, K. (2020). Expanding qualitative research interviewing strategies: Zoom video communications. The Qualitative Report, 25(5), 1292–1301.

Gunkel, D.J. (2018). Ars ex machina: Rethinking responsibility in the age of creative machines. In A. L. Guzman (Ed.), Human-machine communication: Rethinking communication, technology, and ourselves (pp. 221–236). Peter Lang.

Guzman, A. L., & Lewis, S. C. (2019). Artificial intelligence and communication: A human–machine communication research agenda. New Media & Society, 22(1), 70–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819858691

Hanitzsch, T. (2011). Populist disseminators, detached watchdogs, critical change agents and opportunist facilitators: Professional milieus, the journalistic field and autonomy in 18 countries. International Communication Gazette, 73, 477–494.

Hansen, M., Roca-Sales, M., Keegan, J., & King, G. (2017). Artificial intelligence: practice and implications for journalism. Tow Center for Digital Journalism, Columbia University. https://doi.org/10.7916/D8X92PRD

Helberger, N., Eskens, S., Van Drunen, M., Bastian, M., & Moeller, J. (2019). Implications of AI-driven tools in the media for freedom of expression. Institute for Information Law.

Helberger, N. (2019). On the democratic role of news recommenders. Digital Journalism 7(8), 993–1012. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2019.1623700

Helberger, N., Van Drunen, M., Eskens, S., Bastian, M., & Moeller, J. (2020). A freedom of expression perspective on AI in the media—with a special focus on editorial decision making on social media platforms and in the news media. European Journal of Law and Technology, 11(3). https://ejlt.org/index.php/ejlt/article/view/752

Just, N., & Latzer, M. (2017). Governance by algorithms: Reality construction by algorithmic selection on the internet. Media, Culture & Society, 39(2), 238–258.

Leppänen L., Munezero M., Granroth-Wilding M., & Toivonen H. (2017). Data-driven news generation for automated journalism. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Natural Language Generation, Santiago de Compostela, Spain. Association for Computational Linguistics, 188–197.

Lewis, S. C., & Westlund, O. (2015). Big data and journalism: Epistemology, expertise, economics, and ethics. Digital Journalism, 3(3), 447–466.

Lewis, S. C., Guzman, A. G., & Schmidt, A. R. (2019). Automation, journalism, and human–machine communication: Rethinking roles and relationships of humans and machines in news. Digital Journalism, 7(2), 1–19. doi:10.1080/21670811.2019.1577147

Linden, T. C. G. (2017). Algorithms for journalism: The future of news work. The Journal of Media Innovations, 4(1), 60–76.

Loosen, W. (2018). Four forms of datafied journalism. Communicative Figurations Working, 18, 1–10.

Meyers, C. (2010). Journalism ethics: A philosophical approach. Oxford University Press.

Montal, T., & Reich, T. (2016). I, robot. You, journalist. Who is the author? Digital Journalism, 5(7), 829–849. doi:10.1080/21670811.2016.1209083

Mosco, V. (2004). The digital sublime: Myth, power, and cyberspace. MIT Press.

Napoli, P. (2019). Algorithmic gatekeeping and the transformation of news organizations. In Social media and the public interest: Media regulation in the disinformation age (pp. 53–79). Columbia University Press. https://doi.org/10.7312/napo18454-004

Nielsen, R. K. (2017). The one thing journalism just might do for democracy. Journalism Studies, 18(10),1251–1262.

NSTC National Science and Technology Council (2016). Preparing for the future of artificial intelligence. OSTP.

Pavlik, J. V. (2013). Innovation and the future of Journalism. Digital Journalism, 1(2),181–193. doi:10.1080/21670811.2012.756666

Primo, A., & Zago, G. (2015). Who and what do journalism? An actor–network perspective. Digital Journalism, 3(1), 38–52.

Porlezza, C., & Di Salvo, P. (2020). Introduction: Hybrid journalism? Making sense of the field’s dissolving boundaries. Studies in Communication Sciences, 20(2), 205–209.

Porlezza, C. (2018). Deconstructing data-driven journalism. Reflexivity between the datafied society and the datafication of news work. Problemi dell’informazione, XLIII(3), 369–392.

Rydenfelt, H. (2021). Transforming media agency? Approaches to automation in Finnish legacy media. New Media & Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444821998705

Ryfe, D. (2019). The ontology of journalism. Journalism, 20(1), 206–209.

Salmons, J. (2012). Designing and conducting research with online interviews. In J. Salmons (Ed.), Cases in online interview research (pp. 1–30). Sage. doi:10.4135/9781506335155

Schapals, A. K., & Porlezza, C. (2020). Assistance or resistance? Evaluating the intersection of automated journalism and journalistic role conceptions. Media and Communication, 8(3), 16–26.

Schmitz Weiss, A., & Domingo, D. (2010). Innovation processes in online newsrooms as actor-networks and communities of practice. New Media & Society, 12(7), 1156–1171. doi:10.1177/1461444809360400

Sedgwick, M., & Spiers, J. (2009). The use of videoconferencing as a medium for the qualitative interview. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1), 1–11.

Splendore, S. (2016). Quantitatively oriented forms of journalism and their epistemology. Sociology Compass, 10, 343–352.

Stark, B., Stegmann, D., Magin, M., & Jürgens, P. (2020). Are algorithms a threat to democracy? The rise of intermediaries: A challenge for public discourse. AlgorithmWatch. https://www.google.com/search?channel=nus5&client=firefox-b-1-d&q=Are+algorithms+a+threat+to+democracy%3F+The+rise+of+intermediaries%3A+A+challenge+for+public+discourse

Steensen, S. (2011). Online journalism and the promises of new technology: A critical review and look ahead. Journalism Studies, 12(3), 311–327.

Thurman, N., Dörr K., & Kunert J. (2017). When reporters get hands-on with RoboWriting: Professionals consider automated journalism’s capabilities and consequences. Digital Journalism, 5(10), 1240–1259. doi:10.1080/21670811.2017.1289819

Thurman, N., Lewis, S. C., & Kunert, J. (2019). Algorithms, automation, and news. Digital Journalism, 7(8), 980–992.

Túñez-López, J. M., Fieiras Ceide, C., & Vaz-Álvarez, M. (2021). Impact of artificial intelligence on journalism: Transformations in the company, products, contents and professional profile. Communication & Society, 34(1), 177–193.

Turkle, S. (1984). The second self. Simon & Schuster.

van Dalen, A. (2012). The algorithms behind the headlines. How machine-written news redefines the core skills of human journalists. Journalism Practice, 6(5–6), 648–658.

van der Kaa, H. A. J., & Krahmer, E. J. (2014). Journalist versus news consumer: The perceived credibility of machine written news. In Proceedings of the Computation + Journalism Symposium 2014 – The Brown Institute for Media Innovation Pulitzer Hall, Columbia University, New York, United States.

Waddell, T. F. (2018). A robot wrote this?: How perceived machine authorship affects news credibility. Digital Journalism, 6(2), 236–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2017.1384319

Wahl-Jorgensen, K., Williams, A., Sambrook, R., Harris, J., Garcia-Blanco, I., & Dencik, L. (2016). The future of journalism: Risks, threats and opportunities. Digital Journalism, 4(7), 809–815. doi:10.1080/21670811.2016.1199469

Waisbord, S. (2019). The vulnerabilities of journalism. Journalism, 20(1), 210–213.

Wang, S. (2021). Moderating uncivil user comments by humans or machines? The effects of moderation agent on perceptions of bias and credibility in news content. Digital Journalism, 9(1), 64–83.

Weber, M. S., & Kosterich A. (2018). Coding the news: The role of computer code in filtering and distributing news. Digital Journalism, 6(3), 310–329.

Wu, S., Tandoc Jr, E. C., & Salmon, C. T. (2019). Journalism reconfigured: Assessing human–machine relations and the autonomous power of automation in news production. Journalism Studies, 20(10), 1440–1457.

Zamith, R., (2020). Algorithms and journalism. In H. Örnebring (Ed.), Oxford encyclopedia of journalism studies. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780190694166.001.0001/acref-9780190694166-e-779.

Zelizer, B. (2015). Terms of choice: Uncertainty, journalism, and crisis. Journal of Communication, 65(5), 888–908.

Zelizer, B. (2019). Why journalism is about more than digital technology. Digital Journalism, 7(3), 343–350.

Dr. Colin Porlezza is Assistant Professor at the Institute of Media and Journalism and Director of the European Journalism Observatory at the Università della Svizzera italiana. His research interests are the datafication of journalism, the impact of AI on journalism, journalism innovation, and media accountability. Currently, he is also a Knight News Innovation Fellow with the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia University with a project that investigates to what extent journalists can contribute to the value-driven design of AI-technology for automated news production.

Giulia Ferri is a Ph.D. student at the Institute of Media and Journalism and editor of the European Journalism Observatory at the Università della Svizzera italiana. Her primary research interest is the impact of artificial intelligence on journalism, in particular the changing power dynamics between human journalists and machines in newsrooms. Currently, she also collaborates on a publicly funded research project that identifies and evaluates the most important innovations in journalism in five different European countries.