April 26, 2021 | Innovation, International

Journalists from the Global South share how innovation helped their newsrooms to reach new readers, find new stories and combat disinformation

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, Tai Nalon, executive director of Brazilian news organization Aos Fatos, said they saw a flood of disinformation among Brazilians on social media networks.

The digital fact-checking startup quickly set out to combat that with a new tool, Radar Aos Fatos. The tool uses algorithms to root out key trends in disinformation being spread online, track how its spread and then fact check the information in real time.

The digital tool doesn’t simply track the false messages or information being spread, but rather, it follows social media trends that are often indicators of false information: offensive or alarmist terms, use of all caps or misspellings, calls to action to spread the information and virality of a post.

“This is a very common technology we have used to gather information because letters are sometimes inside gifs, inside videos and inside images, so they are not likely to be traceable by text language patterns,” Nalon said.

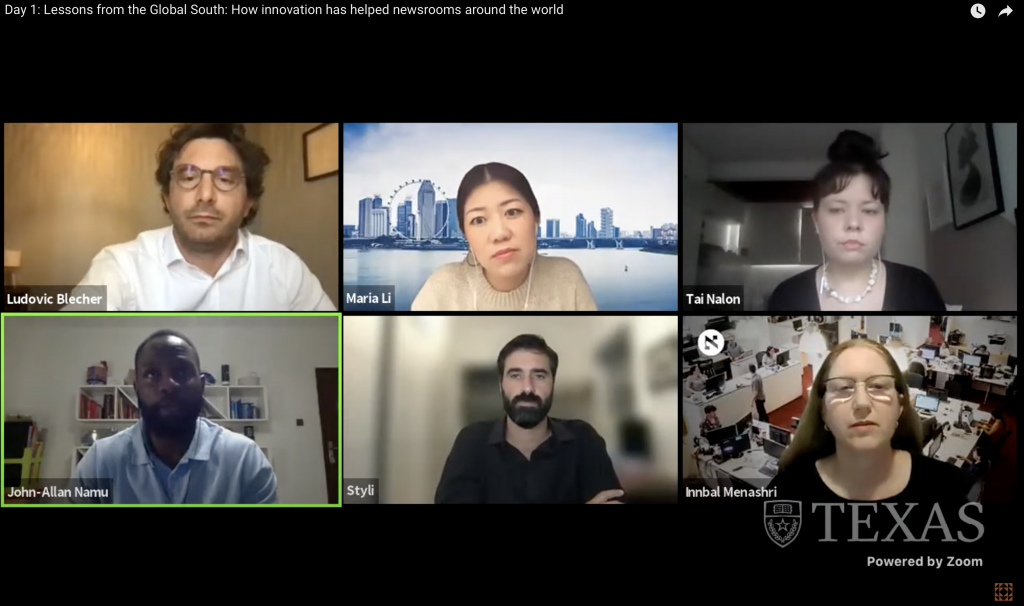

Nalon was part of a workshop on Monday, April 26, at the International Symposium on Online Journalism (ISOJ),where journalists across the globe answered the question: How has innovation helped newsrooms in the Global South?

ISOJ, a program by the Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas at The University of Texas, brings together journalists from around the world digitally to tackle some of the biggest questions in the media today. The conference runs until April 30.

“Innovation is all about implementation of the idea,” explained Ludovic Blecher, head of Google’s Digital News Initiative and moderator of the panel.

Other newsrooms, like Africa Uncensored, developed radically different tools to address a radically different problem.

The Kenya-based organization was faced with the challenge of how to connect with communities out of reach of the internet or their digital tools, said John-Allan Namu, co-founder of Africa Uncensored.

“One of the challenges we noticed was something that I think is perhaps noticed in many other parts of Africa, it’s that the majority of our audiences, and the majority of the public, are not frequently online,” Namu said.

“And they’re not online for very specific reasons: they’re not online for the cost of data, the cost of bundles to be able to get online, to be able to share information, to be able to be a part of that online conversation.”

Similar to Nalon’s Aos Fatos in Brazil, the independent investigative organization sought simple solutions to complex problems: using SMS messages to connect to communities they would normally struggle to reach.

The initiative, called Piga Firimbi, or “blow the whistle” in English, would send out messages and build out a subscription base not just to disseminate information, but also to send questions to the public about their communities and create direct conversations with their readers.

In one case, they asked about health issues in informal settlements, learning that many faced pneumonia and other illnesses likely caused by poor housing and infrastructure.

They would use things like radio, still the most-used resource for news in the region, to report out the information.

“(Our solution) was to take a step back and use a technology that would create the least amount of friction with the largest amount of public who we are interested in speaking to and interested in sharing insights with,” Namu said.

Other journalists, like Styli Charalambous, of South Africa’s Daily Maverick, Maria Li, of Singapore’s Tech in Asia, and Innbal Menashri, of Israel’s Haaretz, developed tools geared toward catering news to users on their sites, increasing engagement and site retention.

Charalambous’ organization used data from its sites and platforms, as well as browsing data, to generate new tools like newsletter and Slack alerts to boost web presence and further disseminate stories.

Li’s Tech in Asia uses the app Tableau to create editorial dashboards to curate content for its start-up’s audience and developed a more refined idea of what content readers are willing to pay for.

Innbal’s Haaretz has sought to boost retention rates by creating an article recommendation tool that not only caters content to readers’ interest, but also offers editor picks to ensure that algorithms don’t just recommend similar content.

Each initiative focused on how to adapt in a changing news environment and deepen their organizations connections with their individual readerships.

Nalon, of Brazil’s Aos Fatos, said such projects can have a larger effect, not just on their audience, but on their entire country.

“Disinformation, at scale, in Brazil, is used in government policy. So, we see lots of politicians, high-ranking politicians, using these kinds of posts in order to engage its supporters.” she said.

“In the newsrooms, those insights are helpful to decide what topics are trending and what to cover.”

Watch video of this panel in English and Spanish on YouTube, and join us for the rest of #ISOJ2021 at isoj.org.